Correggio's angels

Among the countless commentators on Correggio, I like to choose the sincere definition given by Édouard Pommier in a personal autograph letter to me in August 2006, where he considers him “an immense artist.” Such a judgment coming from the then director of the Louvre’s Institute of Advanced Studies has constantly moved me. I must interpret this adjective by applying it also to the continuous happy surprise that Correggio opens wide for us in each of his works, gradually creating in his career that garden of delights and wonders that will be masterful for the new European painting.

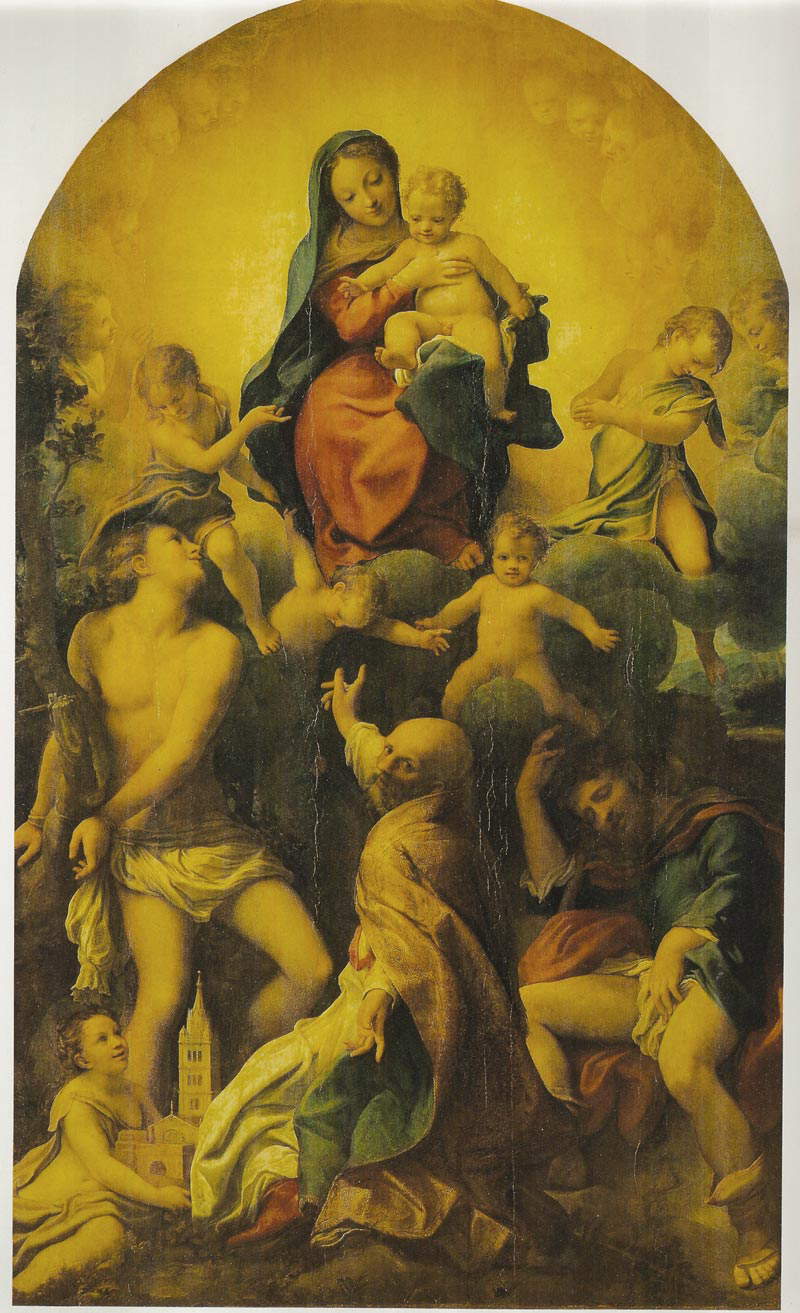

And happy surprise arises, around the year 1524, the enchanting Altarpiece of the Madonna of Saint Sebastian painted for the beloved city of Modena. We are just after the great “tour de force” of the frescoes in San Giovanni Evangelista in Parma, and after the mythical-symbolic adventure of the Allegories for Isabella in Mantua. At this date Antonio has just taken his young bride to the city of his greatest commitments, but he nevertheless retains fragrant friendships in the other places of his youth and with people to whom he is bound by deep feelings. And it is one of these friends, witnessed by Vasari, who in all likelihood gets him the commission, which was warmly accepted; the personage is the influential Doctor Francesco Grillenzoni, obviously from Modena, lay sodalist of the Confraternity of St. Sebastian (founded in 1501), who at the waning of the plague epidemic of 1523 together with his brethren wanted a painting gratifying the saints and the Madonna for the obtained grace of victory over the contagion. The pious congregation had just completed their small Oratory, and the centered panel was to fulfill the primary task of the Altar Major Altarpiece (dimensions 265 x 161 centimeters). The delivery therefore must be calculated to 1524.

For Correggio this was a return to the theme of the central altarpiece, left ten years earlier with the Madonna of St. Francis, and on the other hand this work allows him to inaugurate the marvelous series of great sacred paintings, all of them exceedingly famous and highly esteemed, executed between 1524 and 1530, which are currently admired in the superb Galleries of Dresden and Parma.

Our painter, though constrained by the frontality of the work, pours forth a most free and unseen composition, without deploying any character in symmetry, darted on two segmented and paused diagonals, which hold up the Madonna and Child by way of a chalice at the top, and places St. Geminianus at the bottom in a pose unthinkable for any other master of the time, which is straining and joining at the same time the earthly space of those approaching and the supernal space of Mary and Jesus. It is the arms of the turned bishop that tow from earth to heaven the gaze of the praying faithful, and also ensure the intervening descending intercession of the divine figures. A painting that should have remained forever in this Oratory to give the certainty of communion between those living in the ambages of down here and the caring presence of the immaculate Mother with her Son.

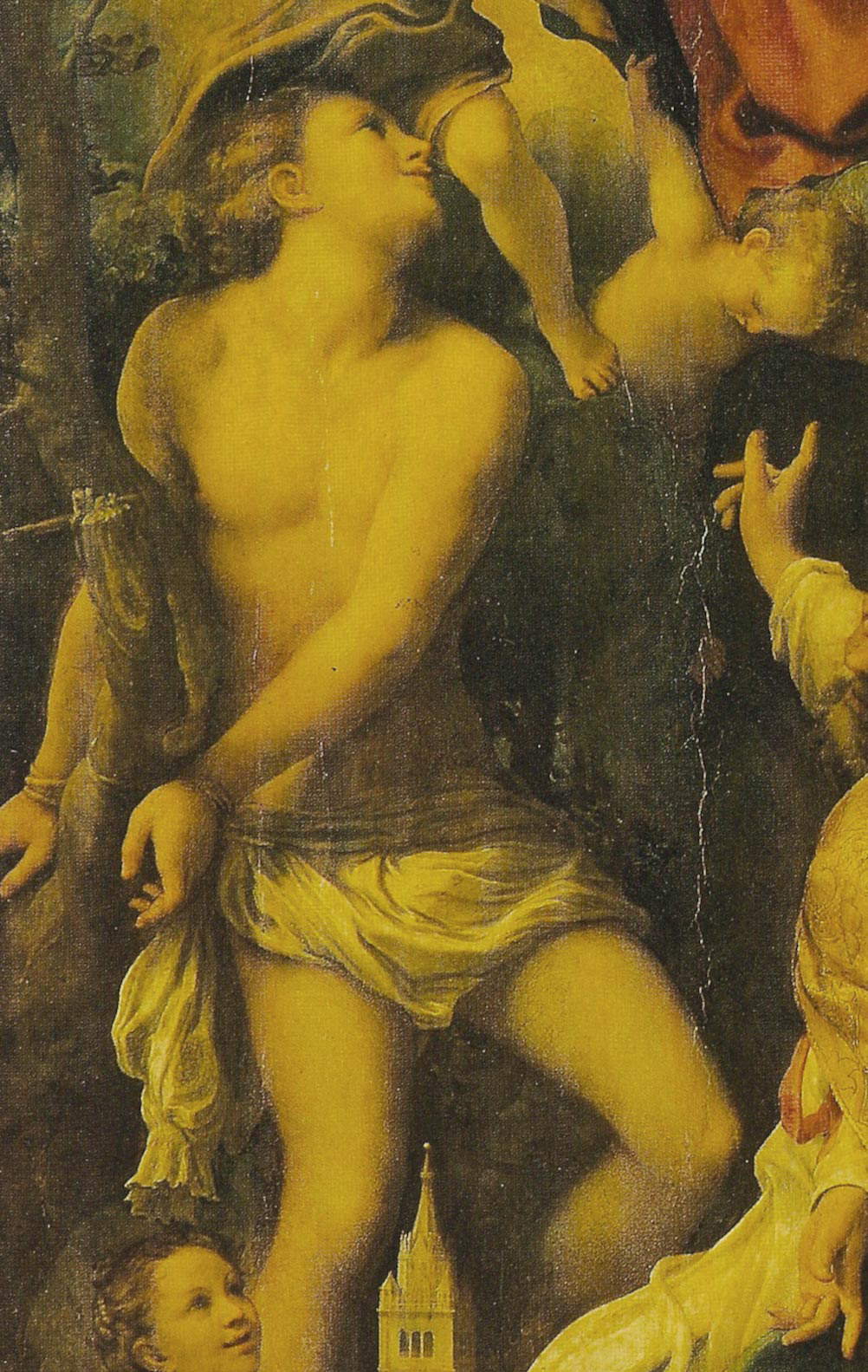

Prominent in the lower part are the two titular saints of the Confraternity: St. Roch lying in the gentle shadow of sleep to our right, as He was healed of His great leg sore during the Dormition, and St. Sebastian, tied to the tree and freshly wounded by a hidden arrow, adhering beautiful like a Greek ephebe in the slender luminous body, aiming joyfully toward heaven. But the accurate participatory transport of Correggio, who was a very young pupil of Bianchi Ferrari in Modena and who opened his eyes here for the first time to the loveliness of Geminian girls, does not forget to make appear (with an unspeakable grace of pure boyhood) an ancillary child, radiant and smiling, to support the model of the city next to the bishop, and gives us a creation that has become dear and famous in the heart of every observer: the unforgettable “Modanina,” innocent and happy.

For the lower figures it is the light that sprinkles the magic of the painting, falling on the bodies as if from a spring behind us, thus bringing forth for us a magical spatial link once again suggested by the capturing idea of the painter, who then (through his specific outpouring of clouds, soft as ever) lets us into the heavens. And behold, the Master of the heavens sends us the paragons as a festive prelude and gradually plunges us into a prodigious expansion of superhuman light, up there in the divine circle where everything is bathed. It is the same light of the empyrean of the dome of St. John’s, inhabited by the same suave spirits, barely biocculated by the impalpable photons of the Allegrian brush.

Here smiles Mary gently holding her Child; here the beautiful Jesus reaches out with spontaneous élan to Sebastiano’s gaze, and here, almost by an insubtractable miracle, Correggio’s soul flaunts the female angels: the suave angels, the unique and cogent crown of divinity.

Let us see in pictures the masterpiece that gave so much honor to the City.

|

| Correggio, Madonna of Saint Sebastian (1524; oil on panel, 265 x 161 cm; Dresden, Gemäldegalerie). Full view. A rare work with a ribbed top, it offered Correggio the cue for an earthly-heavenly composition of extraordinary spatial and vehicular unity, i.e., realizing the identification of the beseeching faithful standing in the Oratory compartment with the intercessory Saints and the invoked Divine Characters. |

|

| Mary and the Infant Jesus. A most sweet package of great humanity, typical of Correggio’s affection, where Mary is intimately pleased to offer the divine Child and where Jesus with a play of hand and foot responds gaily to St. Sebastian’s vivid gaze. Here the grace of health is sweetly granted. |

|

| Mary and the Infant Jesus. A very sweet package of great humanity, typical of Correggio’s affection, where Mary is intimately pleased to offer the divine Child and where Jesus with a play of hand and foot responds gaily to St. Sebastian’s vivid gaze. Here the grace of health is sweetly granted. |

|

| The choir in the empyrean. Heavenly radiance envelops the supreme theophany, crowned by the soft, faint heads of the aiming cherubim. |

|

| Beneath the spiritual evanescence of the vaporous adoring and praising angels, two more bodily visible others turn away from the homage to gracefully observe Saint Roch sleeping beneath them. These are two striking female figures, for only femininity, as Correggio well knew, is filled with beauty. |

|

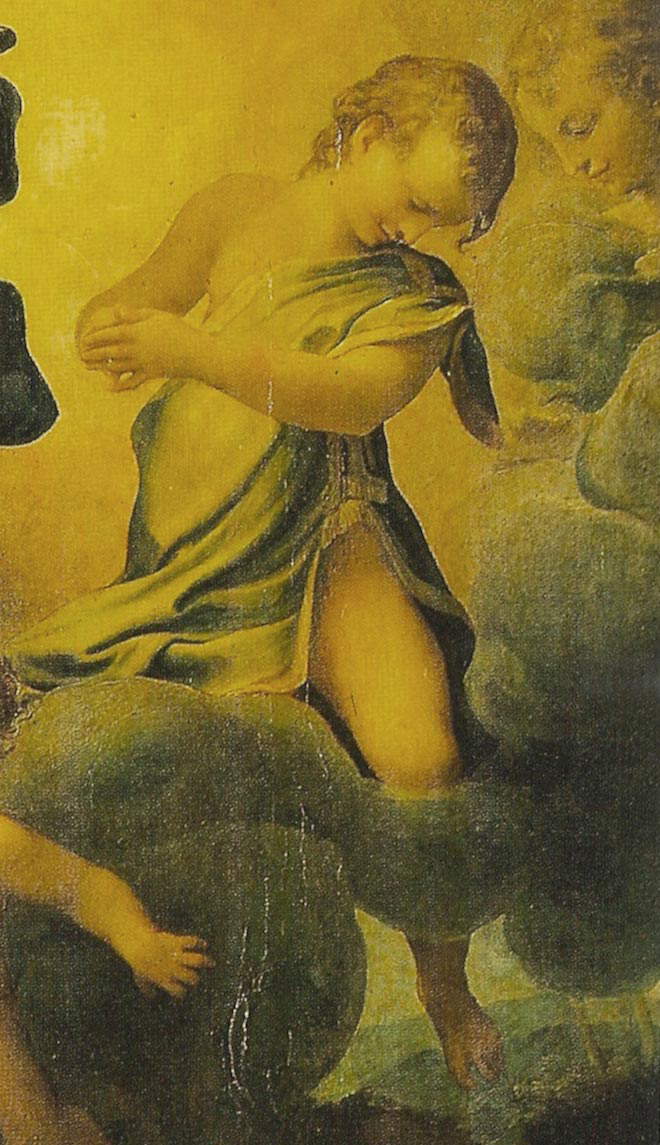

| The two angels on the right, in reflective adoration. Thus Correggio spontaneously loved the features of these spirits, humanized but ethereal. |

|

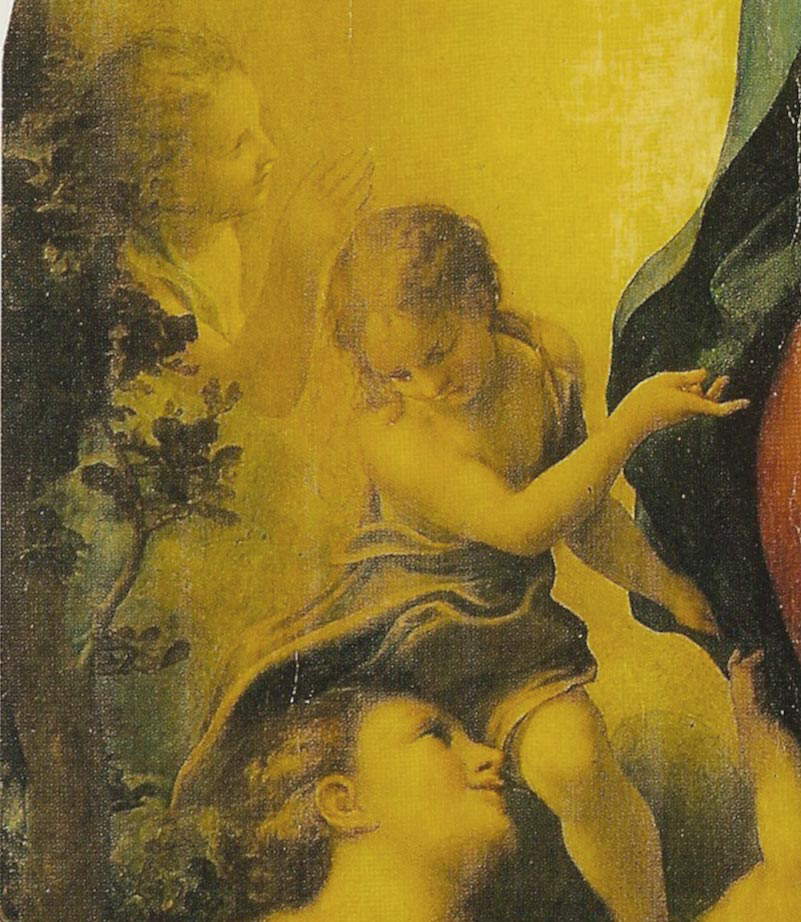

| The angels on the left, most elegant in their gestures of impetration. Mindful of the “virtues” of the Allegory of Wisdom (recently delivered to Isabella d’Este Gonzaga) they enchant us in their youthful venustance. |

|

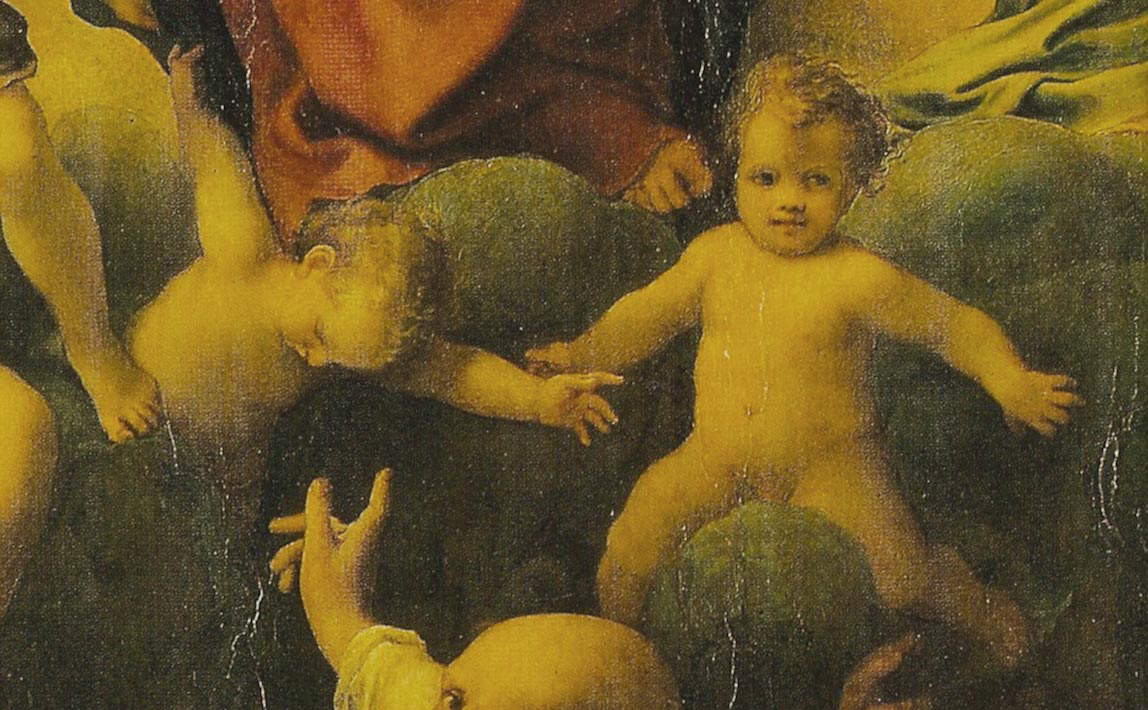

| The two little angels, childlike and naked, are the unpredictable reversal of heavenly spirits becoming flesh, and soft flesh. Their poses, in the entire drafting of the painting, confirm that all the figures in the altarpiece are divorced from spatial perspective, thus gaining a totality of “sacred convention” that is the strength and spiritual dictate of this new painting. |

|

| The stunning Saint Sebastian fully stands out as the pious and strong-willed protagionist of the scene. He is in fact the titular of the religious confraternity devoted to the care of the sick. According to tradition he stands erect and naked in receiving the martyrdom of the darts. But in the gratifying painting he appears rather an animated spokesman for the invocations on the end of the contagion, and a direct confidant of the Child God. Here Correggio offers us the luminous caà non of the Christian ephebe. |

|

| Saint Geminianus’ quivering mediating gesture is Allegri’s resounding inventio: a posture never dared by any master, and one that will impress Caravaggio. The patron saint is truly imminent for the Confreres who stood in the small space of their Oratory and could almost touch his hand; so posed on the ground as to turn the sole of his stocking toward us, but prehensile with his gaze to lead us to the other hand that signals the “remeatio ad coelum” and the thaumaturgical providence obtained. A masterpiece of pictorial and homiletic daring. Here we also see the lying body of Saint Roch, healed in his sleep from his terrible sore. His left foot is a note of the tactile realism that is still typical of Correggio. Above right is the only brief opening to the landscape that connotes the virtual extension of the event, and the suspended foot of the angel defines the prodigy of Jesus and Mary’s descent from divine heaven. |

|

| And here is Correggio’s enchanting “Modanina,” which has so enamored exegetes and literati. She holds up the accurate model of the “dedicatio urbis,” that is, the handing over of the whole city into the hands of God. She has a happy face and a composed hairstyle: she is the intimately joyful symbol of Modena’s gratitude for her newfound health. With this figure closes the circling afflatus of femininity that all intrudes the affectionate Pala. |

Concluding note

The Saint Sebastian Altarpiece has received several restorations. The last in 1975 by Weber, Krause and Flade (from The Dresden Sale, edited by Johannes Winkler, Panini Modena 1989). Yet still in 2015 it showed up with visibly inarquated planks and color falls that can also be caught in these photographic shots. Speaking then benevolently with doktor Andreas Henning, who reminded me that the works on wood would never leave Dresden, I put forward (in exception to what I had heard) the idea of offering a serious restoration of the Altarpiece in Italy in exchange for some permanence for a concluding exhibition. At this proposal the doktor Henning swayed and said that it could be discussed. I should add that my friend Andreas now heads the Museum in Wiesbaden, the spa town considered the most aristocratic in Germany, the Kaiserstadt.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.