Correggio and its importance for the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries

We publish below, as anticipated inBruno Zanardi’s article last May 18, the article written by Francis Haskell in the book that Guanda published in 1990 on the occasion of the restoration of Correggio’s frescoes in the dome of San Giovanni in Parma. It will be followed in the coming week by the other contribution, that of Alberto Arbasino.

Correggio was probably the most beloved painter - although Raphael was undoubtedly the most esteemed - by all people of taste in the 18th and early 19th centuries. This must be the reason why one almost always finds a note of apology in the words of those who dared to reveal their real preferences (and then, as a rule, only in private correspondence) at the comparisons that were constantly made between the two artists. The case of Francesco Algarotti, who wrote in 1759 to his colleague-acquaintance Anton Maria Zanetti about the Madonna and Child, Saints and Angels of Parma known as Il Giorno, is fairly typical of a way of thinking that had been expressed almost two centuries earlier in very similar terms: “Forgive me the divine ingenuity of Raphael, if looking at that painting, I have broken faith with him, and have been tempted to say in secret to Correggio, ’You alone please me.’” Indeed, even with due caution, it seems legitimate to say that in the contrasting works of these two artists-“two angels descended from heaven and returned to it,” in the words of Charles de Brosses in 1740-we saw represented two of the most important elements that coexisted, not always with ease, in the sensibility of the 18th century: the appeal to reason, on the one hand, and the appeal to feeling, on the other. Correggio was the painter of grace, color, tenderness, sweetness, charm, ease, softness. These were all, to be sure, admirable qualities, all without exception-but they were not thought to constitute the highest goals to which an artist could aspire: moreover, some sharp commentators noticed that there was in them a potentially subversive element. Thus Winckelmann pointed out that an excessive love for Correggio could lead to a veritable denigration of Raphael and the accusation of being stiff and sharp, while a quarter century later Sir Joshua Reynolds sternly insisted that an even deeper truth may elude those who pay too much attention to the “little elegances of art.” Once compared to Michelangelo’s sublimity, not only “the exquisite grace of Correggio and Parmigianino,” but even “the correct judgment, the purity of taste that characterizes Raphael” dissolve altogether.

Thus, understanding the lofty place that was held by Correggio in the eighteenth-century imagination is not only important for shedding light on an artistic taste radically different from that of today; it also offers us significant elements for exploring the changes that occurred in the consideration of moral values.

It would certainly be fanciful to claim that the vicious mutilation of Correggio’s Leda (now in Berlin) can tell us as much about similar moral values as about the mental instability of Louis, Duke of Orleans, who in the 1520s threw himself on the painting with a knife. Nevertheless, this incident is revealing because it reminds us how strong an effect the eroticism that can be found in so many of Correggio’s paintings - of sacred subject matter as well as of more explicitly pagan themes - and which was recognized only indirectly by using, in the description of his art, words such as “grace,” “softness,” and others already mentioned. And furthermore, this act of vandalism is interesting for another reason. It was committed in Paris on a painting that had previously been seen in Mantua, Madrid, Prague, Stockholm and Rome.

In truth, the dispersal throughout Europe of the works of this provincial painter seems to have begun already during his lifetime, when Federico Gonzaga of Mantua gave the four Loves of Jupiter-including Leda-(now divided among Rome, Berlin, and Vienna) to Emperor Charles V, who took them to Spain. In the 17th century the acquisition of the Gonzaga collection by Charles I of England brought magnificent Correggios to London, which a few years later, with the dispersal of Charles I’s paintings, found their way between Paris and Madrid. In 1745-1746 the sale of a hundred or so paintings from the Duke of Modena’s collection to Augustus III, Elector of Saxony, was destined to make Dresden one of the great centers of Correggio’s cult, since the paintings sold included his most famous work-the Nativity (known as La Notte). Apart from the frescoes, some very important paintings remained in Parma, either in the churches for which they were made or in semi-public collections. Although the Revolution and the Napoleonic wars were to end up removing many of these paintings, in the years immediately following Waterloo almost all of Correggio’s masterpieces found their permanent locations (it should be noted how little the painter is represented in the United States instead). However, by the mid-eighteenth century-but, for the most part, much earlier-prints had come into circulation reproducing the vast majority of Correggio’s most important paintings, and many oil copies were also remembered. It is hardly necessary to add that many paintings were forged and others were attributed to Correggio with the justification that they seemed to include at least some of the qualities found in his authentic works.

In this way art lovers would have been able to form in most of Europe some idea of the characteristics of Correggio’s style even without traveling to Italy. In England, for example, where there were certainly fewer significant works by Correggio in the eighteenth century than in any other guiding nation, it was perfectly possible for a connoisseur to make a joking reference to Correggio’s “Correggio-ness,” since this allusion to the somewhat unctuous form of religiosity found in his paintings would have been easily understood.

However, it was the Correggios in Italy who, at least until the nineteenth century, attracted the most attention, and it is on the basis of the reactions raised that we can measure the appeal they exerted. These Correggios were in Modena until the best paintings in the ducal collection were transferred to Dresden, and in Parma.

An interesting essay could be written about the effects produced on the notoriety and economy of certain Italian cities by the presence of even very few important works belonging to one of the most admired artists. Today we are surprised, for example, at how much hotels, restaurants and postcard stores in Borgo San Sepolcro and Reggio Calabria should be grateful to Piero della Francesca and the author of the Riace bronzes, respectively. In the 18th century Correggio played a similar role for the people of Parma, where (in the words of the highly influential Cochin) “what is most worthy of attention by amateurs and artists is undoubtedly the number of Correggio’s works that can still be seen there.” More conscientious visitors could go in search of the other glories of that beautiful city (including, of course, the works of Parmigianino), but the main reason they came was the opportunity to see Correggio.

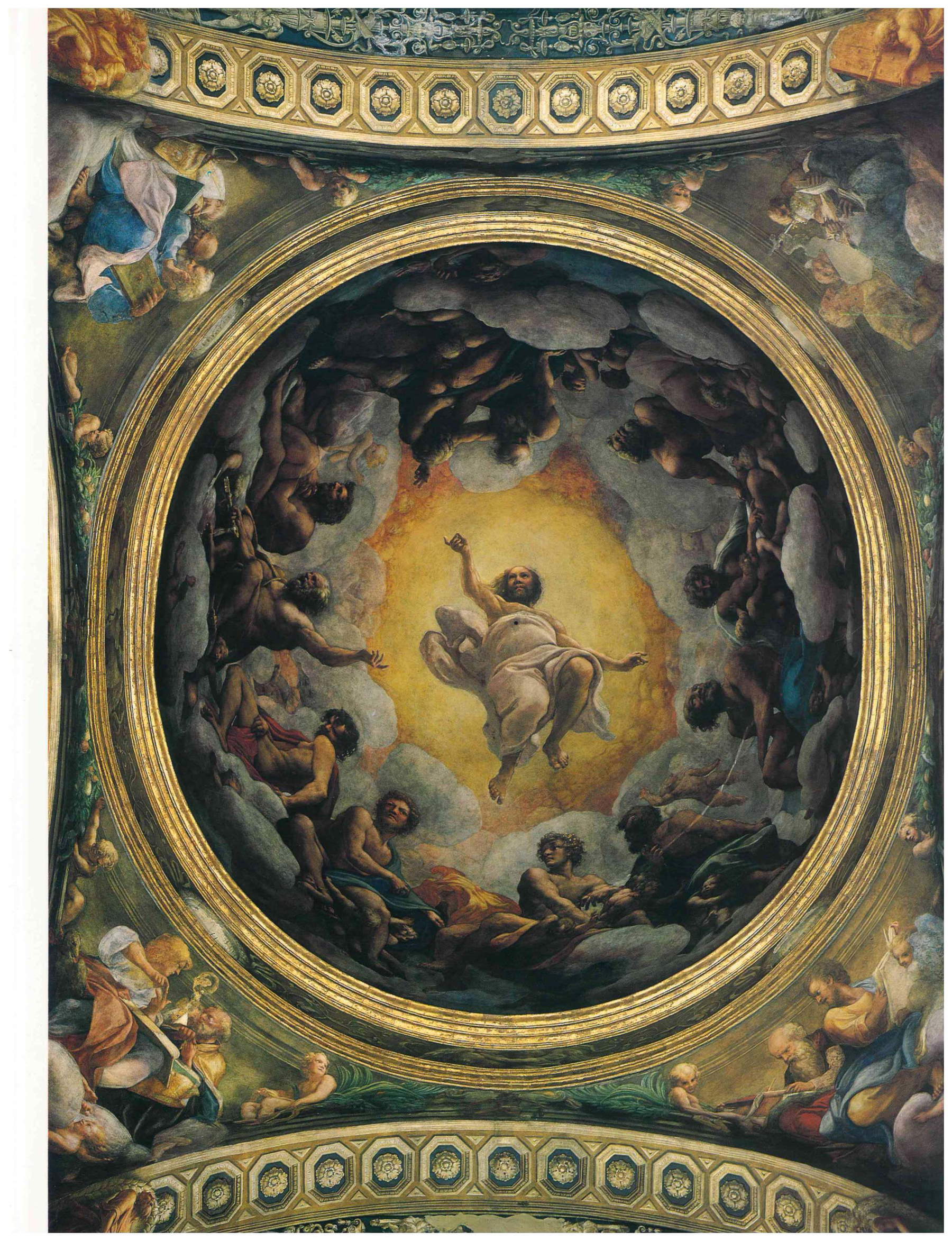

The painting that most spontaneously drew their admiration was The Day, but much enthusiasm also went to the Holy Family, known as the Madonna of the Bowl. In fact, for many visitors there was little else left to see, since they had to agree with Abbot de Saint-Non, who had come to Parma in the company of Fragonard, that “as for the famous domes of that great master, which are to be found either at the cathedral or at the church of San Giovanni, they are so ruined that nothing can be recognized in them anymore.” The frescoes in St. Paul’s Chamber were not accessible and practically unmarked. Nevertheless, some connoisseurs made serious attempts to examine the great dome in the cathedral, and-especially-the one at St. John the Evangelist which (according to common opinion) was much better preserved, although the lighting was deplorable. And what they saw to some extent disconcerted them. They had come to find gentleness and grace, and in their place they found monumental grandeur: according to Cochin the “figures are colossal. It would be difficult to find a convincing reason,” and Gibbon, who echoed this same opinion, thought that “the size of the limbs and the strength of the muscles give them a somewhat too athletic air.”

It was the German painter Anton Raphael Mengs who first resolved this apparent dichotomy in a series of studies devoted to Correggio (to whose works he returned more than once) that are among the finest and most important examples of art criticism to have been written in the 18th century. As befitting an artist who had been called by the names of Correggio and Raphael, Mengs followed the now-established principle of comparing the achievements of the two artists (and also of Titian) and ended up aligning himself with the most widespread conclusion, namely that Raphael should ultimately be considered the greatest. Mengs acknowledged, on the other hand, that Correggio was above all the painter of “grace.” But he totally transformed the character of the discussion by insisting that “grace” was not, as had hitherto been agreed, an extremely enviable (but fundamentally secondary) gift of nature, acquired with all ease by the newly educated provincial genius that Correggio had been. On the contrary, Mengs thought, Correggio must certainly have seen and been able to understand the works of Raphael and Michelangelo in Rome, for only this understanding could have accounted for the grandeur of the frescoes at San Giovanni Evangelista. Correggio may indeed have painted primarily with the intention of giving pleasure; but this pleasure was of a far higher order than had hitherto been suspected: “he was the first, who painted with the end of delighting the sight and soul of the Spectators, and directed all parts of Painting to this end”-and it is the word “soul” that is crucial in this sentence.

For while it is not fair to say that Mengs explicitly acknowledged Correggio’s frescoes in Parma as his most important work, it is certainly to his credit that he made it absolutely clear (for the first time) that the nature of Correggio’s art cannot be said to be truly understood so long as those frescoes are ignored or looked upon only with dutiful respect as if they were exceptional (and slightly ungainly) additions to the sweetness of easel paintings. Mengs undoubtedly knew those easel paintings very well; no connoisseur before him had seen them in such large numbers, or even looked at them so carefully (or, in some cases, when the originals were inaccessible, had looked at their copies). Mengs, too, loved them deeply for all the reasons that had attracted other enthusiasts and was pleased that they were, for example, “of great softness, of excellent dough, and very tasty throughout”; but all this did not prevent him, as it had happened to other enthusiasts, from realizing that his “Drawing is of a grandiose character,” and that on the other hand the naked apostles in the dome of St. John the Evangelist were not, as Cochin and others thought, inexplicably colossal and too much like athletes, but rather “in a style so grandiose, that it surpasses all imagination.” Indeed, Mengs went so far as to say that “none but Michelangelo knew as well as Correggio the science of form, and the construction of the human figure.” For Mengs, in fact, Correggio’s supreme quality was his mastery of chiaroscuro (in which he was superior to Raphael) rather than color, and, above all, Correggio was a painter of great seriousness and culture, perfectly informed about the sculpture of antiquity and the works of his greatest contemporaries. His style and technique deserved to be studied carefully, as, on the other hand, had been done (to great advantage) by the Carraccis and other artists.

Thus Correggio lovers who were aware of the assessment given by Mengs could now for the first time approach their favorite paintings without that slight sense of distrust peculiar to those who thought that Correggio’s spontaneous qualities should not merit such unconditional admiration. After all, it had been proven that Correggio was as important a painter as he was delightful.

Echoes of Mengs can be found in much of the critical literature on Correggio of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, although in the case of Stendhal it is probably more fair to speak of plagiarism than of echoes. It should not surprise us, of course, that Stendhal, who ascribed such transcendental values to the pursuit of pleasure, referred to the “divine Correggio” over and over again in both his works published during his lifetime and those that appeared only after his death, although it is rather curious that he stated that “even today Correggio is almost unknown.” Stendhal traveled through much of Europe-for example, he was overwhelmed by the Correggios he saw in Dresden in 1813, not long after the retreat from Moscow-but since the French army had taken the artist’s finest paintings from Parma, he was able to admire his work in comfort right in Paris. Stendhal’s enthusiasm for Correggio was boundless, but his direct observations tended to be more stimulating in general than acute in individual details. What is, on the other hand, of extreme interest in the context of our essay is the fact that speaking of his masterpiece, The Charterhouse of Parma, in a famous letter to Balzac, Stendhal explained that “the whole character of the Duchess Sanseverina is copied from Correggio (i.e., she produces on my soul the same effect as Correggio)”; and also that the masterpieces in Dresden may have suggested to him two observations that proved to be among the most successful of the entire nineteenth century. Stendhal went so far as to say that these paintings “seen from a distance [...] give pleasure regardless of the subject they represent, they captivate the eye by a kind of instinct”-a concept that was echoed, in a slightly varied form, by Baudelaire in his appreciation of Delacroix and by later generations of connoisseurs eager to emphasize “formal” qualities in art. And by observing immediately afterwards that “Correggio brought painting closer to music,” Stendhal went even further in the direction of nonrepresentational painting and, above all, laid the groundwork for an analogy between these two arts that would in the future enjoy the same consideration that fell to the traditional notion, already then fallen into disrepute, that the two sister arts were painting and poetry.

No similarly important figures would have spoken of Correggio again with such unbridled enthusiasm, but the painter continued to be highly regarded for another generation at least. Of course, the presence of Night and his other paintings in Dresden had made his reputation particularly illustrious in Germany, and we have seen that it was a Dresden native, Anton Raphael Mengs, who wrote most perceptively about him. In Wilhelm Heinse’s curious 1787 novel, Ardinghello, the frescoes in St. John the Evangelist are described in enthusiastic terms; and once in Paris between 1802 and 1804, Friedrich von Schlegel (whose brother August Wilhelm wrote a poem about the artist) proved a subtle, though reluctant, admirer of Correggio. But by then the situation had changed somewhat. Schlegel rejected the Carracci, Guido Reni and other seventeenth-century painters who had always been regarded as Correggio’s illustrious heirs, and acknowledged that it had taken him “a long and very serious study to understand” Correggio. Like Stendhal (who probably derived the idea from him) Schlegel compared Correggio’s paintings to music, but he also recognized in them a majestic solemnity that Stendhal would surely have found misplaced. For Schlegel all the paintings were allegories, “whose task is to represent the struggle and conflict between the principles of good and evil” so that, for example, in Night the beauty of the newborn Christ contrasts with the “guilt and darkness of this earthly world in decay and ruin,” exemplified - rather surprisingly - by the “hideous old man” and the elderly shepherd on either side of the painting. On the other hand, Schlegel was aware that the current was changing, and that “many intelligent artists, educated in Rome [...] reproach this master not a little, because his compositions do not harmonize with their ideas about the correctness of drawing nor with their ideal forms.”

Correggio, who had once dispensed so much earthly pleasure-as had happened again with Stendhal- , now had to be defended as a painter of faith, sincerity and purity. Hegel included him among the artists “at the apogee of Christian painting” and told the audience of his lectures that “there is nothing more lovable than Correggio’s naiveté, which is of a grace that is not natural, but religious and spiritual; and nothing there is sweeter than his smiling, unconscious beauty and innocence.” But this kind of approach could not last long. The cult of the “primitive” was destined to mark the beginning of the end of Correggio’s appeal: in fact, he could not, as was the case with Raphael, be respected for having freed himself little by little from the study of Giotto, Masaccio, and Perugino and for having-at least in his youth-retained something of the virtue and innocence that were recognized in those artists. Correggio was born with original sin (no one knew for sure who his master had been), and this was all too obvious. “We not painters,” wrote the Anglo-Italian Pre-Raphaelite Dante Gabriel Rossetti in 1849, mocking the famous “I too am a painter” that had been attributed to Correggio for more than two centuries. Rossetti’s comment was expressed in a sonnet “after a careful examination of the Canvases of Rubens, Correggio, et hoc genus omne” in the Louvre, and continued, “By God, it’s them or us!”

When Jacob Burckhardt wrote about Correggio in his 1855 Cicero, he acknowledged that “There are those who feel absolutely repelled by him and those who have every right to detest him.” But he thought it worthwhile to go to Parma “possibly in fine weather, if only to see the other works of art there, and to get to know the inhabitants, who by their kindness and courtesy succeed in making one forget the ugliest pavement in Italy.” How amazed previous generations would have been to read these words! To visit Parma “for the other works of art” and for the good manners of its inhabitants! But Burchkardt, of course, did not ignore Correggio. He appreciated his splendid qualities as a painter and as a realist but, Burchkardt insisted, such qualities were not enough, since Correggio lacked everything that can elevate us from a moral point of view so that, for example, he did not realize that by showing all the figures on the dome of St. John the Evangelist in a realistic rather than an ideal perspective, he would end up making Christ look like a frog.

It is also true that a few years later Burckhardt changed his opinion about these frescoes, and that in 1878 he was fully aware of their overwhelming grandeur, which he compared to that of Prometheus and the Titans, but his cautious reaction in 1855 is much more in keeping with a way of thinking that was widespread among those who then rejected Correggio’s art en bloc.

Yet one cannot cite Correggio’s reputation solely as an example of what happened to some artists (such as Guido Reni) whose once uncontested fame was eclipsed in the mid-nineteenth century and regained vigor in the middle of our century. The reason is not only (as has been pointed out in the past) that his paintings were largely protected from the whims of the market. More interesting-and more important for an understanding of European culture-is the fact that his fame, though great, was always somewhat problematic. It was the uncertainty about his biographical events that directly conditioned opinions about his art: for example, was he really never in Rome, as Vasari seems to imply? And if so, how could he have reached a peak of artistic creativity that was almost unparalleled? These questions alone triggered a fervor of antiquarian research that was not accorded to any other painter, not even Raphael: it began in the early eighteenth century and culminated in Abbot Luigi Pungileoni’s three priceless and intolerable volumes published in Parma between 1817 and 1821. Surely Correggio’s life must have seemed quite different from that of other artists: of all those very famous paintings painted in the nineteenth century to illustrate the careers of Renaissance artists, it appears that only those dedicated to Correggio on the basis of Vasari’s scanty account tended to depict him as poor, unhappy and hungry rather than rich, esteemed and courted by rulers."

In one respect, Correggio was certainly impoverished during the nineteenth century. Among the most admired paintings attributed to him in the Dresden gallery was a small Mary Magdalene (painted on copper), lying in a landscape and in the act of reading a book. It would be difficult to exaggerate the ecstasies provoked by this work, and it was probably this same enthusiasm that encouraged Giovanni Morelli, a great but in some cases perverse connoisseur and lover of the tactic of “épater le bourgeois,” to deprecate this “brilliant and somewhat coquettish Magdalene” as the work of some Flemish artist of the late 17th or early 18th century, probably Adriaen van der Werff. Never was a painting by an artist of the same weight-Raphael or Titian, for example-was so much admired to be later removed from its catalog during the ruthless (and usually necessary) purging processes introduced by new connoisseurs; and the effect was clearly devastating. Morelli for his part ensured that it was as ruinous as possible by placing his excommunication of Magdalene in the context of one of those comic scenes he was so fond of inventing: the painting’s defense is entrusted to a “stocky, ruddy-cheeked gentleman” and his weak-sighted daughter, who brings her golden lorgnette close to his eyes, declaring that “there is no other painting in the world so stupendous, so deeply felt... I must confess, Babbo, that I prefer this beautiful sinner by Correggio to all the Madonnas of Raphael and Holbein.” Both are predictably indignant when Morelli tries to demonstrate by a close examination of the painting that the past enthusiasms of a Mengs or a Wilhelm von Schlegel are entirely irrelevant: their taste was, after all, merely the taste of their time... But Morelli forgets to note that his taste is also only the taste of his time, and those who are irritated by his truncated bravado-although they are bound to recognize his real powers of observation and his great flair for comedy-may derive some satisfaction from the fact that some connoisseurs later came to the conclusion that the picture (which was lost during the war) was ultimately painted by Correggio."

It is just that Morelli, like so many other writers, found it much more difficult to come to satisfactory conclusions about the essentials of Correggio’s art than about any other master: his nature was “simple, naive and delicate, but somehow also morbidly excited”; his later paintings for churches were conventional and lacked freshness; Correggio was in his true element in Greek mythologies. And-in an ingenious attempt to resolve all possible paradoxes-Morelli declared that “no one has ever represented sensuality to us so spiritualized, so naive and so pure, as Correggio.” In the light of so much nineteenth-century criticism, we can see that Morelli also tries to gain the painter to the cause of purity, but without appreciating certain aspects of his art that might have been more authentic to him and his eighteenth-century admirers.

The constant shifts in tone that we find in discussions of Correggio’s art in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries can be illustrated by a series of questions, the number of which could be further increased: did his training take place in the provinces or in a large city? Was Correggio facile and superficial or cultured and refined? Was he voluptuous or pure of spirit? Was his inspiration essentially pagan or Christian? Was he naïve or aware of his own means? Was he really a Renaissance artist or, by nature, a Baroque painter born out of season? All these questions, which can never be answered, were repetitive and become tedious. But they are not insignificant. The ambiguities at the heart of Correggio’s paintings represent a challenge to our idea of what we expect from art in general; they force us to consider, as happens with the works of very few other painters, what we really mean when we speak of aesthetic pleasure. These are questions, then, really important and not merely pedantic. As well, when we discuss the importance of an artist, we generally think about his importance to other artists-not just those who look directly at his achievements. In this sense, Correggio’s place in art history is also a dominant one, and if this essay were to deal with his legacy in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, this place would have to be discussed at length. For the debt owed to Correggio by such first-rate artists as Federico Barocci, Annibale Carracci, Giovanni Lanfranco, and Gian Lorenzo Bernini (to name but a few) is so great that we are entitled to declare that Correggio changed the entire course of art history. When we come, however, to the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the situation is somewhat different. Not, of course, that Correggio’s presence is no longer felt: indeed, during the eighteenth century traces of his influence can be found almost everywhere, in France in particular. But one feels that Correggio is no longer inspiring new and daring artistic achievements, as had been the case with previous generations. Correggio had been too easily absorbed into the blood of painters such as François Boucher and no longer carried with him a distinct presence; on the contrary, it was when Boucher’s influence began to wane and the new severity introduced by David seemed to assert itself unchallenged, that the impact with Correggio returned to original and fruitful significance. It was the talented (and strangely forgotten) Pierre-Paul Prud’hon who turned to Correggio for a more original and more fruitful form of inspiration than the way Correggio himself had appealed to Rococo painters, and it was Prud’hon who brought Correggio’s legacy to the field of nineteenth-century art, where it was eagerly picked up first by Diaz and later by Henner. These are very small names when compared to those of Annibale Carracci and Bernini, but it becomes interesting to bring them all together, the great as well as the small. Correggio is certainly one of the few great artists whose influence has always been beneficial. Art history is littered with the names of Raphael and Michelangelo’s victims, but Diaz and Henner are surely much better artists than they would have been had they not discovered Correggio.

Fortunately, however, the restoration of the frescoes in St. John the Evangelist will soon make it clear that its importance demands much more of our attention and that, as we raise our eyes to them, we will find ourselves (in the words of Mengs) in the presence of a “style so grand that it surpasses all imagination.”

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.