Comedian (banana and tape on wall): a work in which everything is Maurizio Cattelan

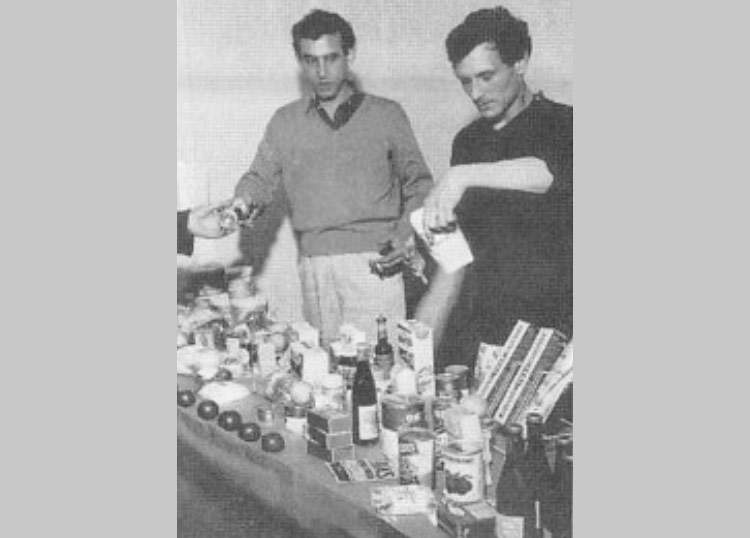

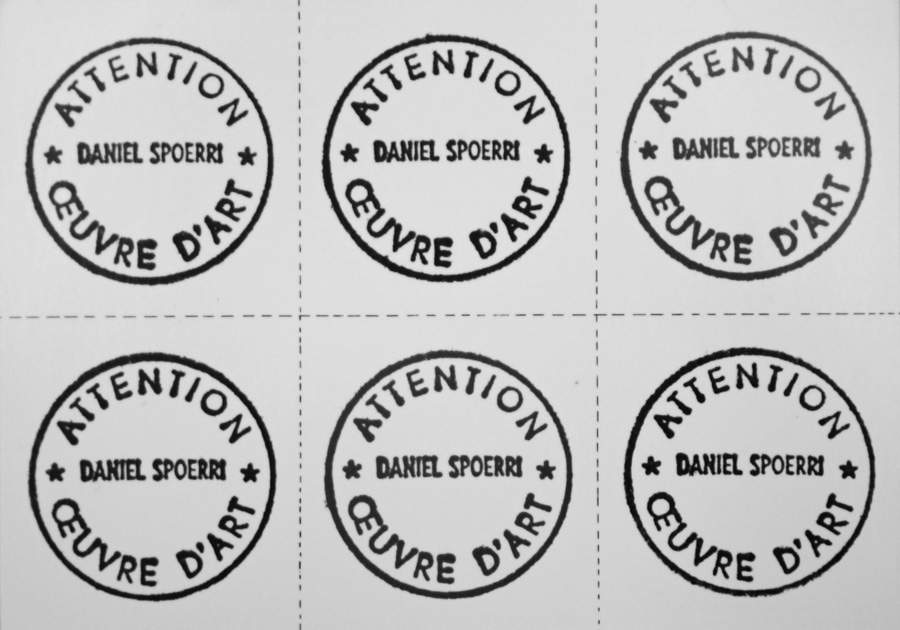

It may seem strange to say, but Maurizio Cattelan ’s banana has an illustrious precedent when it comes to food elevated to the status of a work of art. And certainly we are not talking about seventeenth-century still lifes filled with fruits of every species and variety, nor Claes Oldenburg’s ice creams and giant hamburgers, much less Giovanni Anselmo’s Eating Structure (where the head of lettuce was part of a whole in which the inescapable rotting of the vegetable played a central role), least of all of Andy Warhol’s acclaimed banana that most have (pertinently) juxtaposed with Cattelan’s new Comedian, the banana taped to the wall of Perrotin’s booth at this year’s edition of Art Basel Miami Beach. None of that: here we are talking about real food sold to collectors as artwork. It was in 1961 when a former Hamburg artist turned gallery owner, Addi Köpcke, organized an exhibition of Daniel Spoerri’s work, entitled Der Krämerladen, in his Copenhagen gallery: the space had literally been transformed into a grocery store, with real food that collectors could buy (sure: at the current market price of the object, not at tens of thousands of dollars like Cattelan’s banana). On the kinds that were bought, Spoerri affixed a stamp with the words Attention, oeuvre d’art stamped on it. Cattelan, on the other hand, guarantees those who buy his banana a certificate of authenticity, suggesting, however, that they change the fruit the moment its condition makes it no longer usable.

Spoerri’s primary intent was not so far removed from that which might animate Cattelan’s banana: Spoerri questioned whether a tomato ended being simply a tomato the moment one elevated it to a work of art. The answer lies in the value placed on that tomato: when the collector buys it as a work of art, he is aware that he is participating in a great spectacle, and as in a spectacle, fiction becomes truth. The banana is a new act in this show, the most recent, perhaps not even the most irreverent, certainly not the most original. And the title that the artist has chosen, Comedian, should make it blatant and obvious that the banana, quite simply, continues to hold up the curtain.

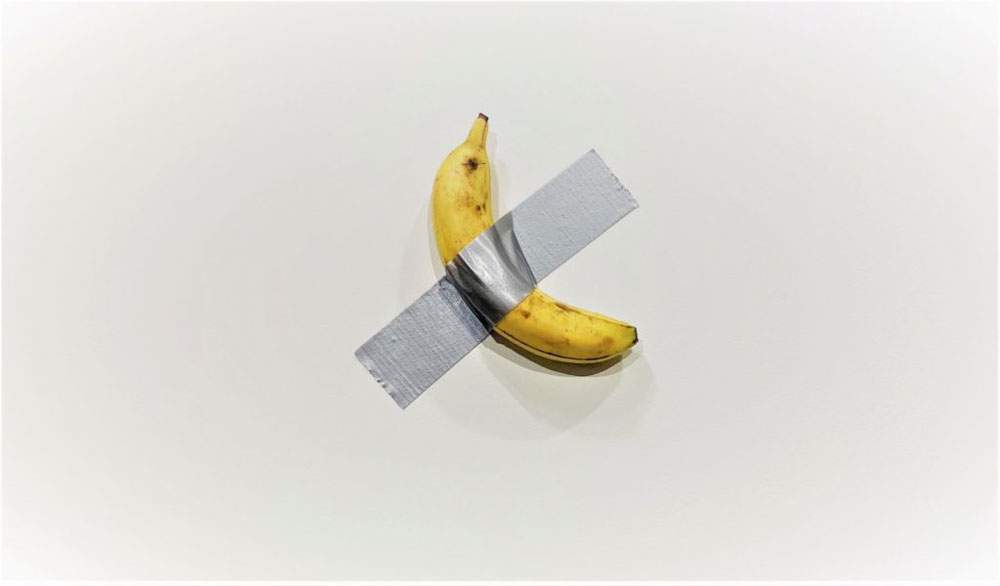

To this reflection can be added the observation that, as is usually the case in any credible show, the play works only when performed by titled actors. Sticking a banana on the wall is not a sufficient and necessary condition to call oneself an artist: it is the path taken to get to that banana that transforms it into a work of art and grants it an unequivocal status (it matters little whether one considers it an interesting work or, vice versa, a dull work, and it matters little whether one considers it a stunt by the artist: after all, it is undeniable that this latest proposal by Cattelan is animated by an ironic, goliardic, burlesque vein: if anything, it will be a question of who the recipient of the prank is), it is the work that the artist has done previously that divides Cattelan from any vain imitator or from the sleazy country fair painters who attack him not yet having clearly understood that art, in the last hundred years, has undergone some modifications and some developments and is no longer stopped at portraits of old women or glimpses of lavender-flowered countryside. And in Comedian everything is about Maurizio Cattelan, everything is Maurizio Cattelan. The white wall, the banana mottled with brown spots that has reached the peak of its ripening process and will soon begin to decay, the duct tape that fixes it to the wall, the commercial value attributed to the work, the media hype, the public reactions, the critics’ divisions.

|

| Maurizio Cattelan, Comedian (2019) |

|

| Addi Köpcke and Daniel Spoerri sell food-works of art at the exhibition Der Krämerladen held in 1961 in Copenhagen at Köpcke’s gallery |

|

| The stamps Daniel Spoerri affixed to food items for sale at the 1961 exhibition Der Krämerladen |

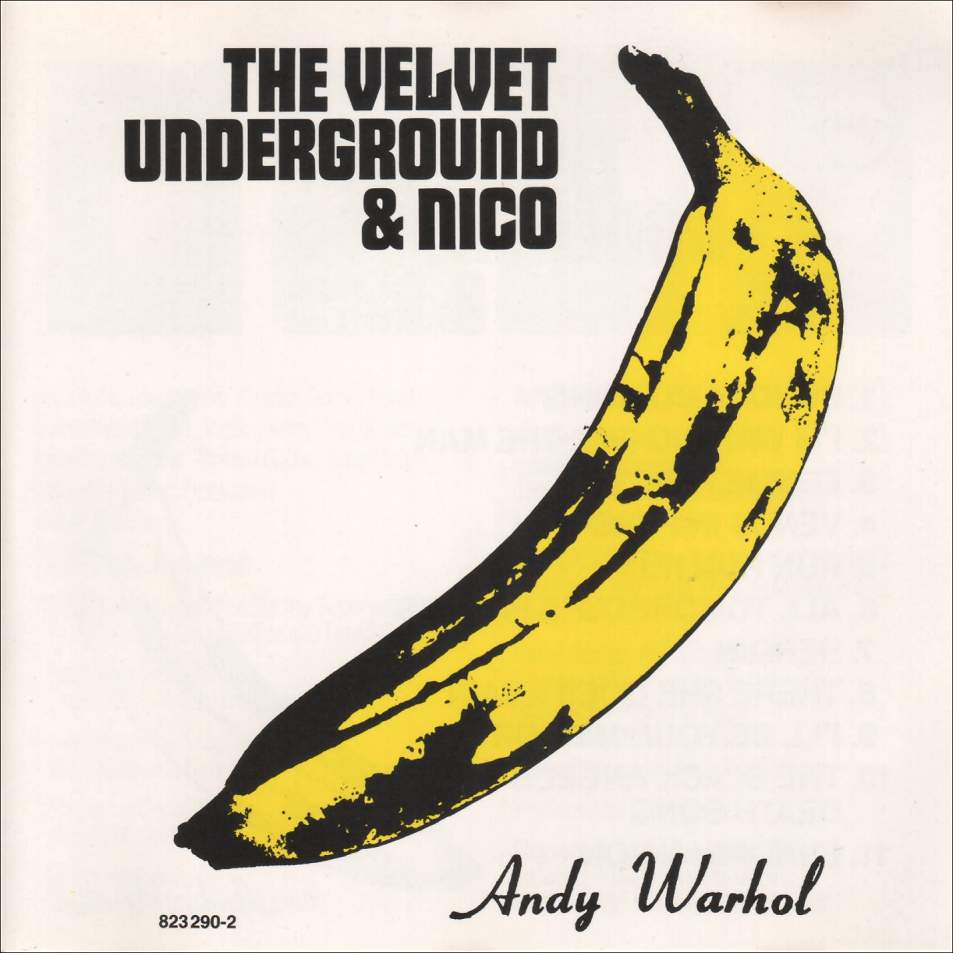

Almost sixty years have passed from Der Krämerladen to Comedian, and in the meantime art has experienced numerous other fundamental contributions. The most frequent comparison, as noted above, tends to trace the origins of Cattelan’s banana to the one that Andy Warhol, also in the 1960s, imagined for the cover of The Velvet Underground & Nico, a seminal album by Lou Reed’s group released in 1967. The reference is not just formal. Both fruits share a penchant for double entendre (in one edition of The Velvet Underground & Nico, the banana could literally be peeled by removing a sticker, and underneath appeared the rose-colored fruit, a clear phallic allusion), and above all, it is unlikely to think that Cattelan was not mindful of Warhol’s musings on the reproducibility of art. In an interview, the Pittsburgh artist had clearly stated that if one cannot afford a painting, one can resort to a poster of the work one would like to see in one’s home. The Paduan goes further and allows anyone to create their own Cattelan, their own Duchampian ready-made even in a perfectly philological manner with the original material in a matter of seconds, and what is more, starring an object that, in the perfect Warholian tradition, breaks down any kind of barrier, since a banana remains a banana for anyone, whether for the collector willing to pay more than a hundred thousand dollars for it or for those who can do nothing more than spend a handful of cents to obtain the fruit with which to obtain Cattelan’s work. Perfect continuity even with one of Cattelan’s most recent works, America: it seems that to explain his golden latrine, Cattelan said something like "whether you eat a two-hundred-dollar meal or a two-dollar hamburger, the result is identical toilet-wise." That is, from the perspective of the water closet.

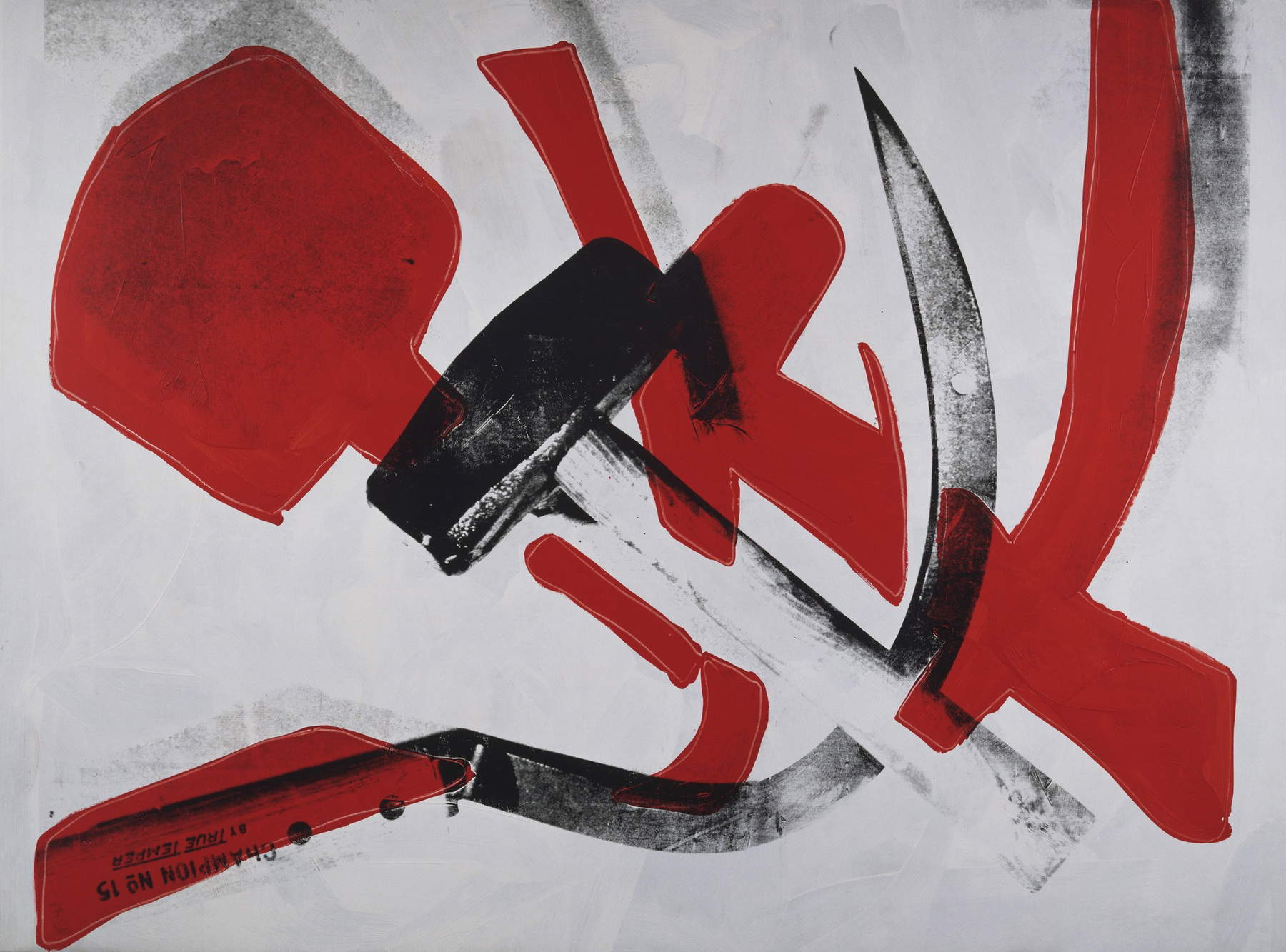

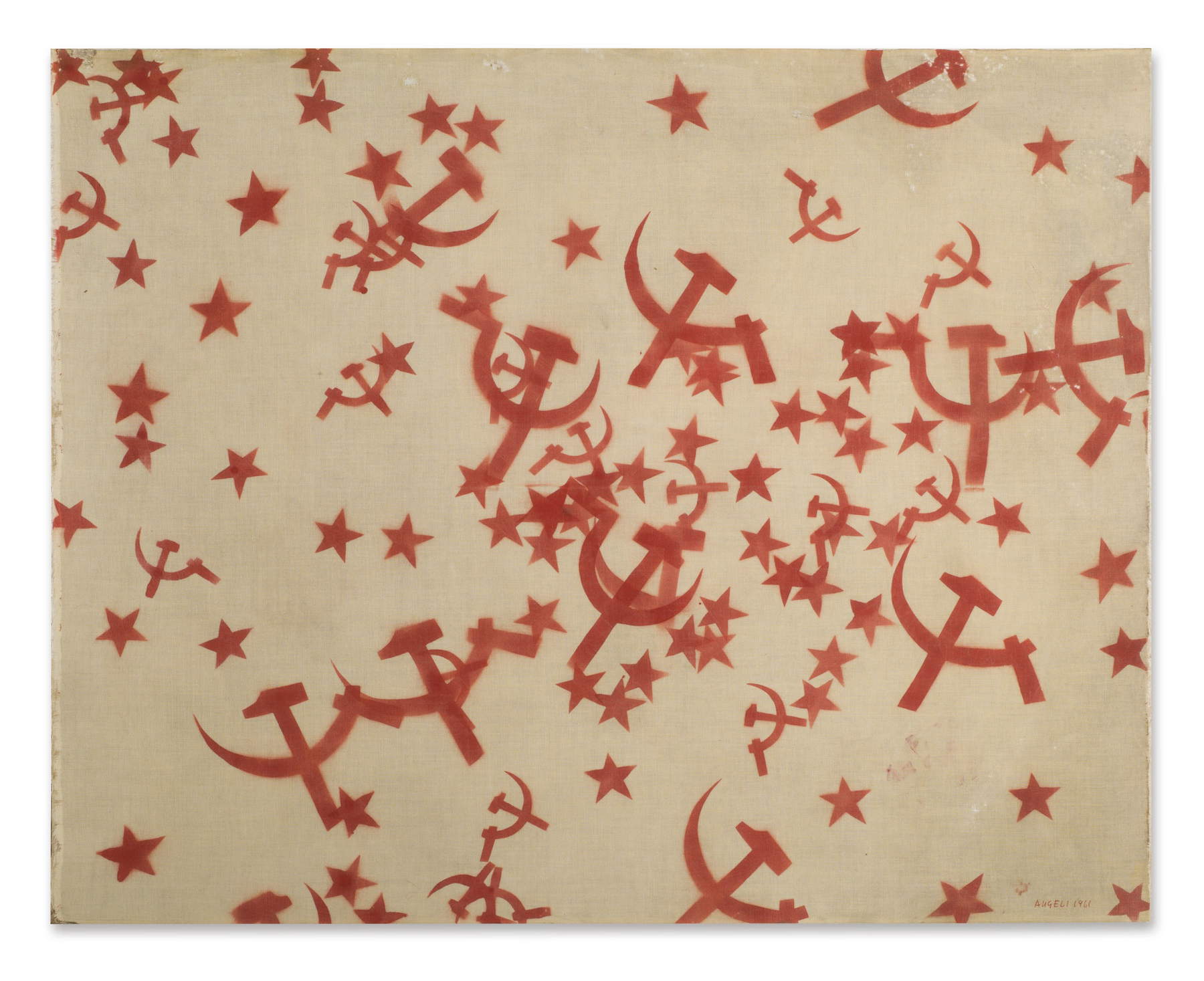

Still, it is hard not to think (or at least this is the feeling) that the banana does not glamorize itself with those political meanings that, from The Ninth Hour to America, from Him to Charlie don’t surf, have always connoted a relevant part of Cattelan’s production. Warhol again reduced the hammer and sickle to a pop icon, Franco Angeli turned it upside down and mixed it with other symbols to convey to the observer an everyday life made of signs and a politics for which the masses were fired up: Cattelan seems almost to continue by turning the symbol upside down in turn, making manifest its perishability, charging it with a (very high) economic value. To find political significance in the banana, it would be the most effective portrait of the current world gauche that has been produced recently. Few artists in the history of art have managed to pull off such corrosive political satire with so little: if, then, in Comedian, this Hogarth-esque figure of his from the 2000s is unintentional (though it is hard to believe), so much the better.

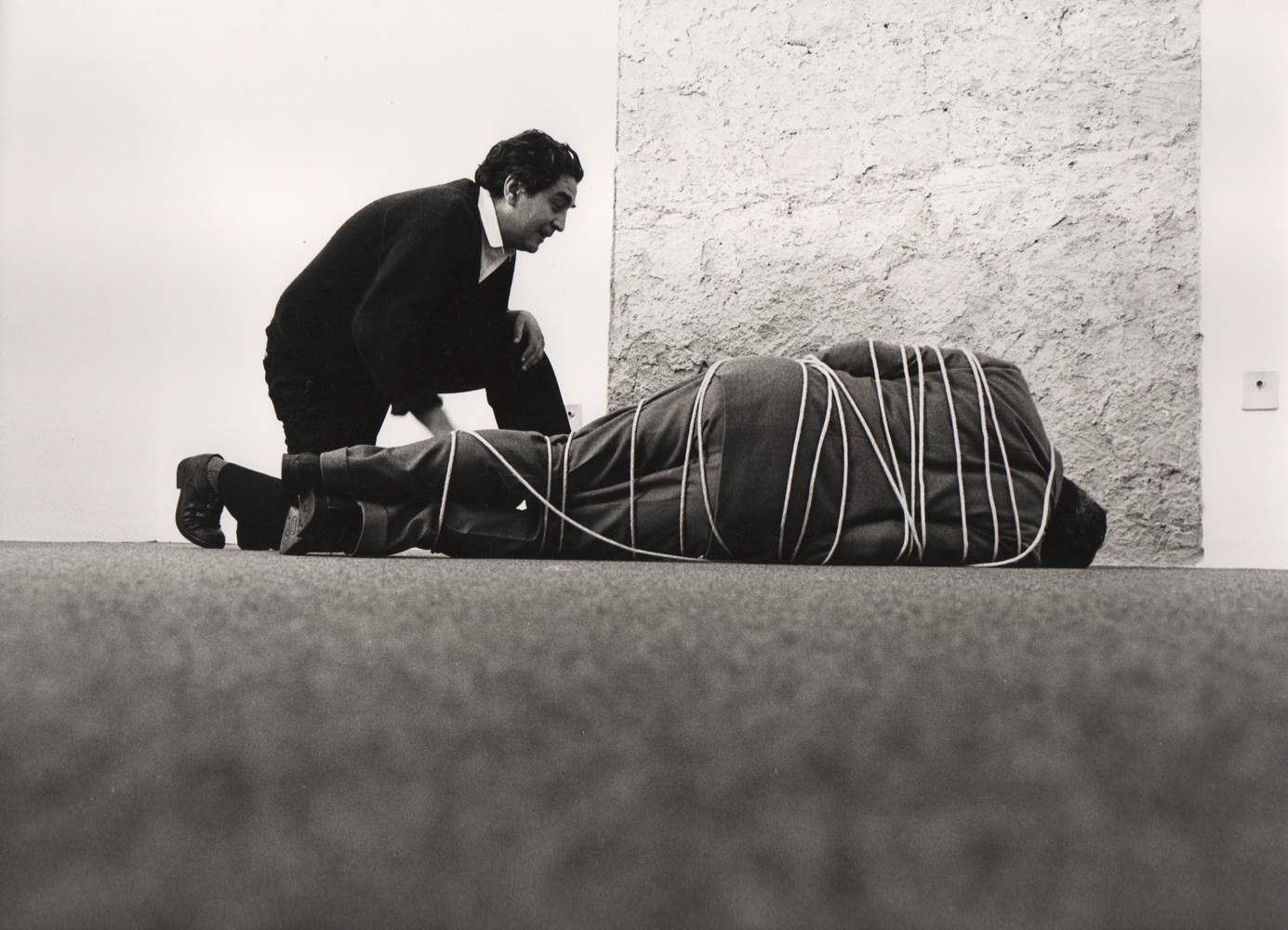

And then there is the self-quoting Cattelan, since it is impossible not to think of the time when, with A perfect day, exactly twenty years ago, the artist hung Massimo De Carlo (with the same adhesive tape as the Miami banana) on a wall of his own gallery. To explain A perfect day, Francesco Manacorda argued that, on the one hand, Cattelan sticks the merchant on the wall exactly as the latter does with the goods he sells, staging with that expedient yet another self-referential paradox, while on the other hand the act of De Carlo’s posting represents the extreme apex of the relationship between artist and gallerist: every implication that brings in money, power, market, according to Manacorda undergoes a destabilization enacted by that sadistic gesture (in the true sense of the word: at the end of the preview of the performance, De Carlo had fallen ill, lost consciousness, and ended up in the emergency room) that evokes a crucifixion and that goes far beyond the gesture of Vincent D’Arista, who in 1970s Naples bound Pasquale Trisorio like a sausage, making him lie on the floor of his gallery with the intention of destroying the gallery and the gallerist. Cattelan had not merely tied him up: he had crucified him and, though unintentionally (or so one imagines), sent him to the hospital. And only a year earlier, for a solo show of his at the Rivoli Castle, Cattelan had placed some shopping carts underneath the works (and what are, and what have works of art always primarily been, if not commodities to which an exchange value is always paid? We’ll have to remember that, when enraptured we admire a Raphael Madonna). Even earlier, at the 1993 Venice Biennale, invited by Achille Bonito Oliva who was the curator of that edition, instead of presenting a work Cattelan symbolically rented out the space that had been allocated to him, later granting it for use to a fashion company to advertise a perfume. And there are many other examples that make clear how Cattelan’s art has always led disenchanted reflections on the role of the market.

|

| Andy Warhol, The Velvet Underground & Nico (1967) |

|

| Maurizio Cattelan, America (2017) |

|

| Andy Warhol, Hammer and Sickle (1976; New York, MoMA) |

|

| Franco Angeli, Stars (1961; Private collection) |

|

| Maurizio Cattelan, A Perfect Day (1999) |

|

| Vincent D’Arista, Don’t step on me (1975) |

|

| Maurizio Cattelan rents his space at the 1993 Venice Biennale. |

And speaking of the market: is Cattelan’s banana a speculation, as many have already hastened to write? Perhaps, but in that case it would still be a simple emergence of a system that has deeper roots and on which it would be necessary to develop a much broader reasoning that goes beyond the contents of Comedian. On ARTnews, Andrew Russeth tried to give himself an answer by writing that "there is an underlying issue regarding the disparity of forces in the contemporary art industry, where a small group of artists and dealers amass fortunes while everyone else has to make a living doing a second or third job. One could see Cattelan’s Banana as a stinging caricature of this imbroglio: an out-of-touch artist who decides to amass some extra income in his spare time in a way that only he is allowed to. Comedian is a disturbing joke, and it’s about all of us." That Comedian is a work grounded in a palpable, overwhelming and perhaps even violent mocking charge is an assumption hard to deny. It seems reductive, however, to reduce it to a game, a caricature, a provocation (by now Cattelan, at almost sixty years of age, what more would he have to provoke, at least in the worst sense of the term, the one understood by all those who in these hours speak of provocation?).

Comedian is something more: first of all, it is a work that conveys content, even if we do not want to believe it and even if we want to pretend that it does not say anything just because, after all, we are talking about a banana hanging on a wall. It would be interesting to find out who was the first to assert that immense bestiality that art should need no explanation: who can say they go into the Uffizi and understand works like Michelangelo’s Tondo Doni, Andrea del Sarto’s Madonna of the Harpies or Titian’s Venus of Urbino without needing someone to illustrate them? Invoking D’Annunzio, what is art criticism if not the art of enjoying art? And Cattelan has offered us nothing but a work that we can all literally enjoy. Possibly even without seeing it live.

And in any case, Comedian is a work that, however you want to think of it, finds an extremely coherent place in Cattelan’s journey: it is pure theater, it is a show within a show, it is a new drama of which Cattelan is the director (a director of those who perhaps care little or nothing about audience reaction), and of which we are spectators whose job it is to decide how we find the play: we can be amused, sad, serious, bored, furious, know-it-all, indifferent, rancorous, frustrated. It does not matter. And equally little does it matter whether the work actually sold or not, or whether Cattelan’s work is considered, all things considered, to be as uninnovative as it actually is, or unavoidably anchored in his postmodern language: after all, even when we visit any art history museum we see legions of artists who are little or not at all innovative. The interest that Cattelan continues to arouse also lies in the fact that we are all ready to become more or less involved spectators of every most minute action that flashes through his mind.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.