But while honored and esteemed by all, Cesare was enjoying a tranquil life; behold a strange and sudden accident, which, like a violent whirlwind, hurled him from the summit of happiness to the depths of no more thought of accidents, and suffocated him in an abyss of bitter misfortunes. The passage is taken from the Vite de’ pittori, scultori et architetti genovesi by Raffaele Soprani (1612 - 1672) and refers to the episode that changed, in a negative way, the existence of one of the most esteemed painters of the late 16th century in Genoa, Cesare Corte (1550 - after 1619). A cultured, elegant painter, an excellent connoisseur of philosophy and literature, a fine poet, considered by all to be an amiable gentleman who easily won the soul of every one. His refined disposition, combined with his mastery with brushes, soon enabled him to become one of the most prominent painters in Genoa of his time: he worked tirelessly, was never to be found without the company of some noble knight, and obtained the most prestigious commissions, including those of the prince of Massa and Carrara, the Genoese Alberico I Cybo-Malaspina.

There was, however, at some point in his life, an episode that tragically ended his career. What then was theunthought-of injury, which doppo many prosperities made the Painter unhappy? Laura Stagno, an art historian at theUniversity of Genoa, has recently dedicated a study to the Cesare Corte affair: the study is also available in its entirety on the web and is entitled “”Uno strano, & improviso accidente“: la vicenda del pittore eretico Cesare Corte.” The episode that disrupted Cesare Corte’s life was therefore, as can be guessed from the title of Laura Stagno’s contribution, anaccusation of heresy, which was brought against him in 1612. It is the two major biographers of the Genoese painters of the time, namely the aforementioned Soprani and Carlo Giuseppe Ratti (1737 - 1795), who describe to us in broad strokes how things went. Or at least, how they apparently went. In fact, the story goes that Cesare Corte received a cassette from a French friend who had to return to his homeland and who, Ratti lets us know, was named Orlando Enrì: the latter tore Cesare a promise to guard the object carefully until his return. As chance would have it, his friend never returned from France, because he died, so the painter decided to open the chest: he found it full of books branded as heretical by the Church. We do not really know what these books were, but we do know that they were mostly written in Greek: this was no obstacle for Caesar Corte, who knew Greek well and therefore had no difficulty in understanding their contents. Biographers tell us that he read them avidly, despite the fact that they advocated doctrines that were not in line with Catholic orthodoxy, and that he then began to write similarly empij concepts: in particular, Ratti again lets us know, a commentary on theApocalypse of John that was completely contrary to the Church’s interpretation.

Cesare Corte was thus denounced to theInquisition. It is worth pointing out that not only was it obviously forbidden to spread concepts considered heretical, but also the mere possession of books placed on the Index was forbidden, so much so that, as historian Mario Infelise notes, “after 1559,” the year of publication of the so-called Pauline Index, the first Index of forbidden books, “the possession of books became the most frequent element of accusation in trials for heresy,” although it was not easy for the guilty to be prosecuted on the basis of mere possession: it was, however, very common for this offense to aggravate already compromised situations, such as Caesar Corte’s might have been. After the denunciation, he was in fact imprisoned: it was December 30, 1612, and given the risks he was about to run, he decided to publicly abjure, in the church of San Domenico, his convictions. He was then given the penalty of perpetual imprisonment, with the obligation to remain on a regime of bread and water every Friday, to recite prayers daily, and to confess and take communion four times a year. The harsh conditions to which Cesare Corte was subjected in prison undermined his physique, so much so that he died ill in prison, probably after December 1619, when he was allowed (we know this from documents) to paint in prison.

Laura Stagno posed a question: is it possible for Cesare Corte to have matured ideas considered heretical in such a short period of time? The answer is that we need to consider the environment in which the artist was formed and lived. His father, Valerio, was an artist originally from Venice, and we know how the Serenissima was, at the time, the protagonist of fierce clashes with the Church: Valerio, himself a cultured intellectual, would have continued to maintain relations with his city of origin, which has led scholars to think, given also Valerio’s strong interest in atapina art such as alchemy (an interest that, according to Raffaele Soprani, would have caused him to squander much of his wealth), that the artist was oriented toward thoughts and interests suspicious of ecclesiastical authorities. In addition, Cesare Corte traveled to France (Laura Stagno speculates that it was there that he met the friend who would deliver the forbidden books to him) and to England, where he worked for Queen Elizabeth, who was excommunicated in 1570 by Pius V. There is therefore no doubt, according to Laura Stagno, that Caesar Corte frequented places and environments where the Protestant Reformation had found wide diffusion: these circumstances would therefore have predisposed him to accept heretical thought.

However, it is very difficult, if not almost impossible, to find traces of Cesare Corte’s heterodoxy in his works. Various conjectures have been made in this regard, but they often turn out to be in forcings that can easily fit either a view that considers Caesar Corte a heretic or a view that instead considers him a quiet observer of orthodoxy. The painting that hints at the greatest possibility of seeing in Cesare Corte an artist who strayed from the mold of Catholicism is a Pieta preserved in the Oratorio del Carmelo in Loano, in the province of Savona, and derived from a drawing by Michelangelo now preserved in Boston.

|

| Left: Cesare Corte, Pietà (c. 1610; Loano, Oratory of Mount Carmel). Right: Michelangelo Buonarroti, Pietà for Vittoria Colonna (c. 1540; Boston, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum) |

|

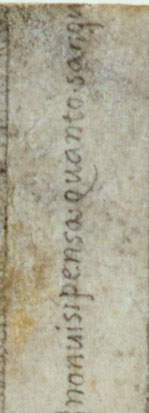

| The Dante verse in Michelangelo’s Pieta |

The iconography of the Pietà for Vittoria Colonna, which takes its cue from the Nordic and Venetian Pietàs, which introduce the motif of angels helping the Madonna to support the body of Christ, is faithfully reproduced by Cesare Corte in his painting for Loano. Certainly the painter became acquainted with Michelangelo’s work through one of the many copies circulating as early as the late sixteenth century: indeed, the work met with widespread success, and not only in Reformed circles. Even the commission to Cesare Corte of the Loano painting matured in the sphere of strict Catholic observance: the requester was in fact Andrea II Doria, a member of the famous Genoese family, marquis of Torriglia and count of Loano under the name Andrea I. The sources remember him as a pious and strongly devout man: we do not know, however, whether the choice of subject was due to him, and in case it was due to Cesare Corte, we cannot know whether the revival of Michelangelo’s design was intended to allude to reformed instances. Arriving at a decisive conclusion is not possible, not least because in the trial to which Cesare Corte was subjected his works are not mentioned: we are therefore convinced that around this matter there is still investigation to be done.

For those who would like to learn more, precisely on these issues, and precisely on the Cesare Corte affair, Laura Stagno will give a lecture on Thursday, February 18, 2016 at 5:30 p.m.: the appointment is in Genoa, at Palazzo Lomellino.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.