Cen Long, a dissident outsider in contemporary Chinese art

Zeng Fanzhi, Zhuang Hui, Chen Zhen, Liu Wei, Liu Bolin, Sun Yuan and Peng You, Ai Weiwei, Xu Bing, Cai Guoqiang, Chen Zhen, Huang Yongping: these are probably the first names of artists that the Western art-loving public considers as the most representative exponents of the contemporary Chinese scene, complicit in the fact that almost half of them have chosen to pursue their careers in Europe or America. If one tries to trace a lowest common denominator among these heterogeneous poetics expressed in such different languages, one could perhaps observe how they share a vocation for the environmental dimension, a post-Pop-like attraction to the object and the search for an immediate communication that rejects sophisticated conceptual mediations. Thinking back to the works seen in the main fairs and events, the national artistic attitude appears extremely compact and self-sufficient in hybridizing with the local tradition stylistic suggestions inferred syncretically from the main Western art currents, such as Impressionism, Surrealism, Informalism and Hyperrealism, which only in the 1980s were cleared through customs in China after nearly three decades of embargo. Thematically, Chinese art appears variously engaged in reworking the consequences of the rapid and uncontrollable urban growth linked to the Westernization that succeeded the 1966-1976 Revolution, in denouncing the rural pockets of backwardness in areas unaffected by this development, and in didactically re-presenting the vestiges of a millennia-old culture in the form of refined souvenirs for the use and consumption of “laymen.” However, despite the apparent alignment of artistic productions, the impression is that there is something that eludes and that the cultural and experiential substrate that constitutes the matrix is much more complex and contradictory.

China is a diverse reality that is still largely unknown to us, starting with the real repercussions of governmental cultural policies on artistic creation in terms of both the domestic circulation of works and their export, both areas that are in different ways related to the issue of the construction of the country’s official image. While during the government of Deng Xiaoping (leader from 1978 to 1992) the launch of the “Boluan Fanzheng (拨乱反正)” program aimed at correcting the harms of the Maoist revolution coincided with renewed economic openness and unprecedented freedom of individual initiative, violent were the social unrest and government oppression, culminating in the Tiananmen Square massacre. Those years saw a significant introduction of existentialist suggestions linked to emotional introspection, aspects long precluded from artistic research because they were considered expressions of a bourgeois attitude, and, for the first time in the history of the People’s Republic, unofficial art appeared as a cohesive phenomenon committed to undermining the uniformity imposed by Maoist culture. The subsequent collapse of liberal ideals brought, in the 1990s, a wave of disillusioned pragmatism, which was followed from the 2000s by a decided market orientation, following the importation of the hierarchical mechanism of sales, auctions, exhibitions, large collections, and festivals (most famously, the Gwangju Biennial) on which the Western art system rests, which Chinese art policies began to place alongside public commissions.

In recent years, in parallel with the multiplication of public and private spaces dedicated to contemporary art and the rise of Chinese artists to star status on the international stage, the country has experienced a sharpening of thestate interference in the private lives of citizens, which is expressed in widespread controls in public places and means of transportation, in the encouragement of dissenters’ denunciation of official thought, and even in the censorship of such culturally fundamental terms as “criticism,” even as applied in its artistic sense. Many are the questions raised by such capillary intersection of public and private and by its grafting into a very diverse starting context already marked by a millenarian culture, of which it is very difficult on the outside to have the correct keys to interpret in relation to a contemporary artistic production at first glance so marked by a synchronic and decontextualized assumption of languages elaborated elsewhere. With the era of Socialist Realism over, is there any art today that can be called state art? What tactics of resistance are adopted by artists and movements that distance themselves from both the temptations of business and governmental interference? What repercussions do the contradictions of the present and the equally discordant legacies of the past have on artists’ imaginaries?

This sketchy historical excursus and the resulting questions are the prerequisite for trying to contextualize the work of Cen Long (Guangzhou, 1957), a dissident Chinese painter currently at the center of a structured promotional tour in Europe by the Crux Art Fundation, a Taiwanese foundation set up ad hoc by curator Metra Lin, which for the past fifteen years has taken on as its mission to make his work known outside the borders of China. This operation is extremely interesting in many ways: on the one hand, it reveals more clearly than other situations what lies behind the “construction” of the positioning in the art system of an artist who, by choice, has always been an outsider to it, and on the other hand, since Cen Long is an outsider with respect to his culture of belonging, his works allow us to plumb “negatively” the aforementioned issues, highlighting their internal logic. First and foremost, the painter’s biography is exemplary in this regard: born in 1957 in Guangzhou, the largest coastal city in southern China, the artist is the son of Cen Jia Wu (1912-1966), a famous anthropologist and historian persecuted during the Cultural Revolution, who at a young age directed him toward a cultural education with an international scope, stimulating him to study Western art, philosophy and traditions. Fundamental tool for the artist is his father’s very rich library, crowded with books in Chinese, English, Japanese, French, Russian and German, much of which was later confiscated or destroyed. At a young age he was entrusted to a guardian in Lyon, France, to protect him from the turmoil that inflamed China, and there he became acquainted with European visual culture by visiting local museums. Upon his return home he took up watercolor technique and as a boy, like many young intellectuals of the time, was sent to the Tianmen countryside initially to do compulsory physical labor, then as a teacher at the local middle school. Later, he qualifies to become a member of the army’s Art Division and is assigned the task of helping participants in military art exhibitions in the execution of their works and producing performances to relieve soldiers of the burden of war. The troops to which he is assigned control the provinces of Henan, Hubei and Hunan, arid regions dominated by wilderness where he comes into deep empathic contact with the hard lives of the inhabitants.

In 1979, Cen Long left the army to enroll in the Xi’an Academy of Fine Arts, and in the 1980s he participated in the New Wave movement, initially driven by a commitment to fighting power structures and their conditioning on artistic expression (a legacy of the Cultural Revolution), then resulting in a dismantling of traditional culture through Western languages and aesthetic methods. Then Cen Long distanced himself from this current as well and began working as a professional painter at the Wuhan Academy of Fine Arts. After a temporary move to Japan, pretending to be a student at Nagoya University, actually working as a lecturer in the art department, he returned to China where he resumed teaching at the Hubei Institute of Fine Arts and, as an artist, abstracted himself from the national circuit, which he felt was vitiated by corruption and factiousness. It is in this phase, dating from the early 2000s, that his mature style is specified, marked by the integration of Western and traditional Chinese techniques and, from a thematic and compositional point of view, by the abandonment of the depiction of crowds of characters with realistic though stylized connotations in favor of solitary figures, timeless emblems of a heroically militant humanity in the epic of life. Despite the esteem held for him by fellow artists and students for his intellectual stature and revolutionary teaching of the textural values of oil painting in open contrast to traditional Chinese characters bound to two-dimensionality and the dominance of the graphic sign, in recent years he has chosen to leave his academic career to pursue his research with greater freedom.

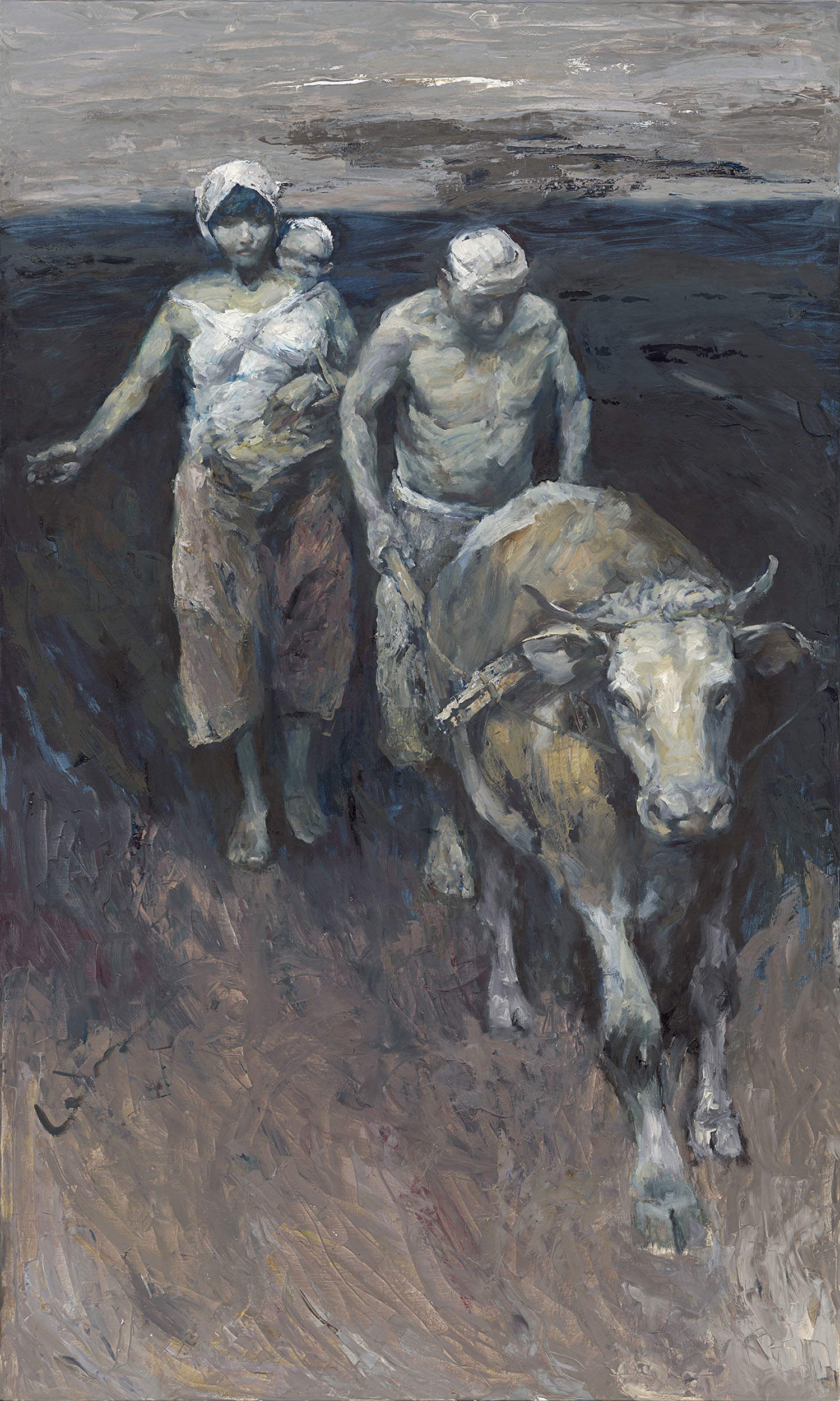

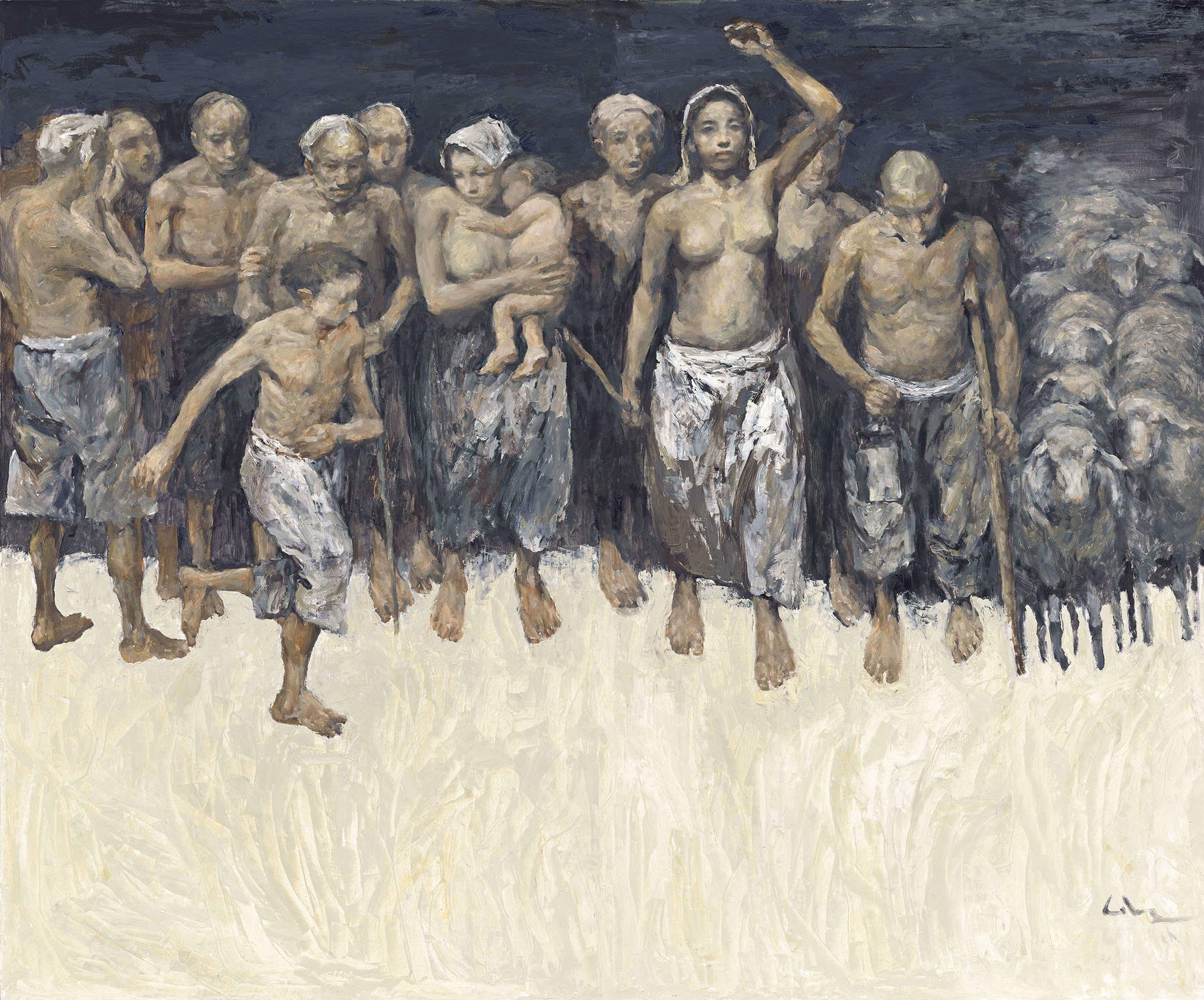

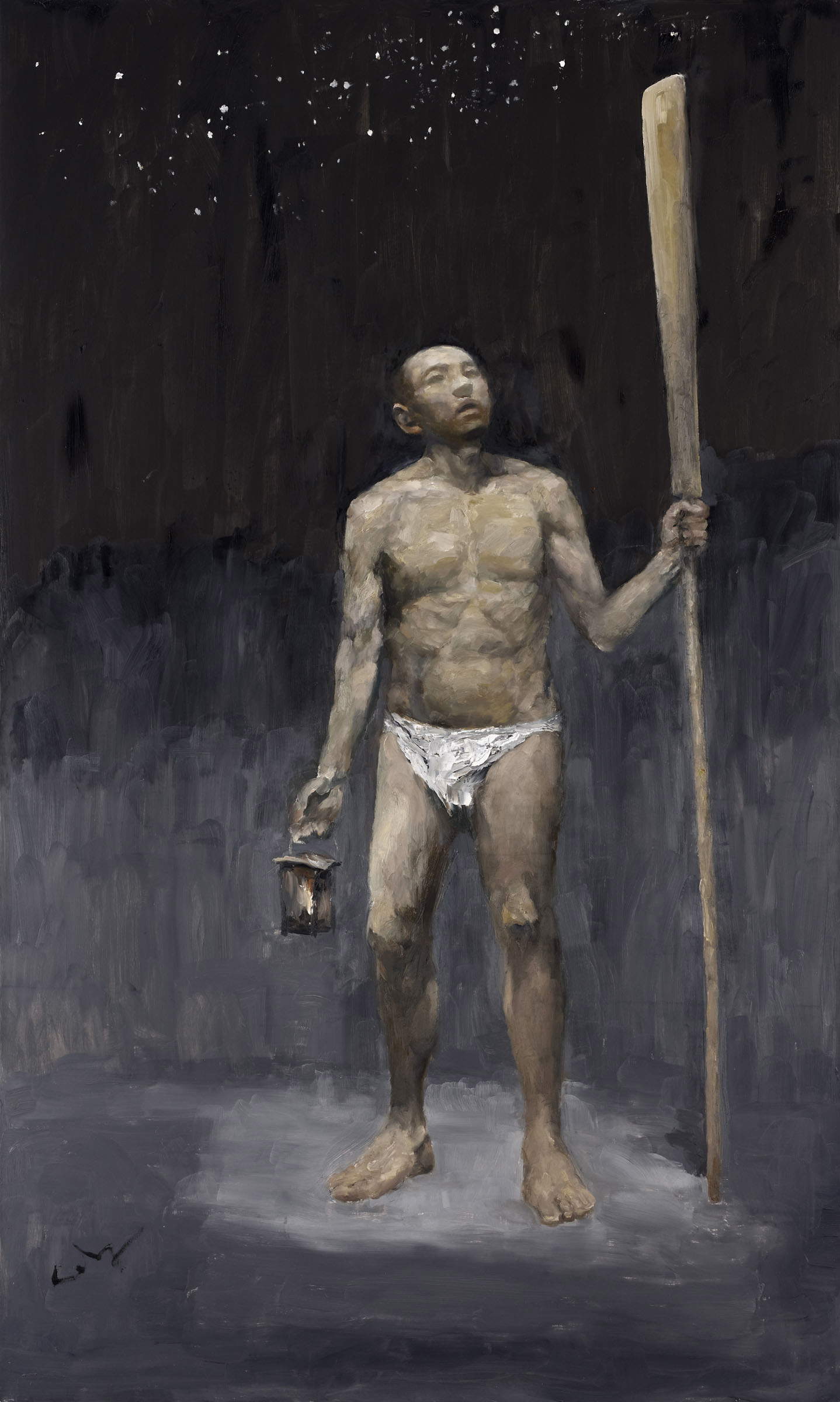

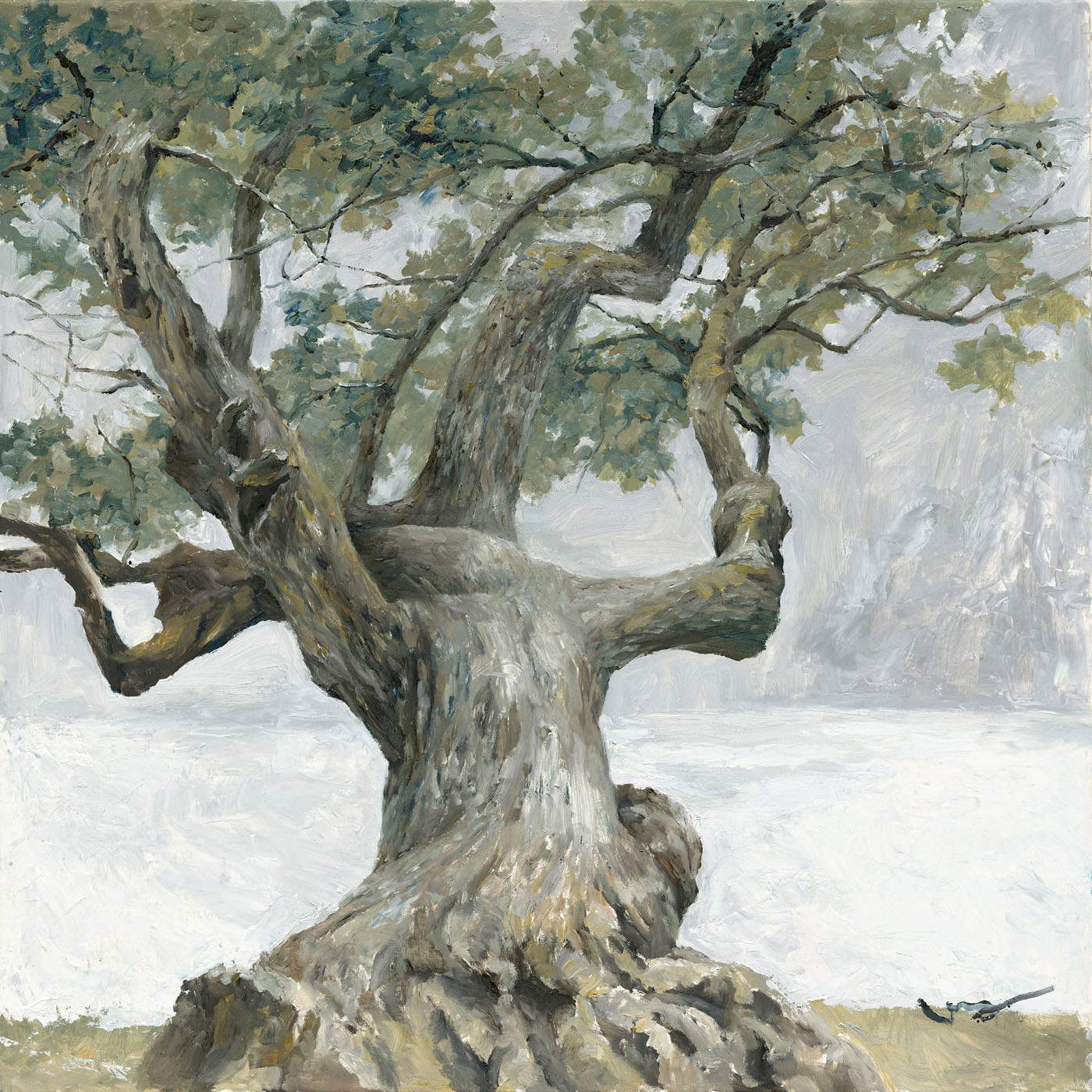

Cen Long’s paintings reject all political allusions for a spiritual quest untethered from a precise religious belief and portray a humanity without place or time, whose representatives are humble characters monumentalized by painting. Half-naked, partially paluded by classical draperies, they stand out against abstractly nocturnal backgrounds as they perform labors such as plowing, sowing or fishing. Their faces have no precise somatic denotation and often resolve into sketches of veiled drafts. Even when they are more detailed, they do not aspire to ethnic recognition or individualization, but to the sublimation of an asceticism that expresses their purity of soul and attunement to the beauty of creation, conditions that the artist hopes may coincide with the essence of humanity tout court. The anatomies, especially the male ones, are evoked by compendious brushstrokes, which on the one hand are precise in indicating the position of muscles, bones and tendons, but on the other hand seem to evoke the impermanence of the human bodily envelope, destined to dissolve into a nature made of the same substance. In the female bodies, mostly prosperous and maternal, what is exalted is the whiteness of the flesh at times rendered purplish and livid by the weather, as in the case of the female fishermen who plunge into icy waters in search of oysters, shellfish and crustaceans. Also very important in his compositions are the animals, personifications of innocence and docility, often endowed with a psychological and emotional accentuation superior to that of human beings, who as we have seen are treated as universal paradigms. In contrast, the backgrounds on which the figures and even the more extensive surfaces of the draperies are powerful pieces of abstract painting, dominated by the pleasure of color and matter.

Cen Long’s expressive figure attempts a difficult balance between the diverse suggestions of the authors of Western art history he has most studied, such as Gustave Courbet, Eugène Delacroix, Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo, Lucian Freud, and the great masters of the 17th century, such as Frans Hals, Diego Velázquez, Antoon van Dyck, and Rembrandt, which appear amalgamated into a coherent stylistic distillate. Thematically, his favorite subjects are a consequence of both the teachings of his anthropologist father, who encouraged him to explore the traditions of China’s ethnic minorities, and his youthful experiences in the rural provinces following the army. But on closer inspection, this ensemble, at first glance so deliberately divorced from instances related to current events, can also be interpreted as a radical political opposition ciphered by an author for years in voluntary exile in his studio, who even goes so far as to write his personal diary in Russian. In fact, the intent to honor workers by capturing the essence of their daily lives in order to represent their spirit and strength corresponds in equal and opposite ways to that of Socialist Realism, in which the gladness of workers and peasants in contributing to the realization of the communist utopia was expressed by the elimination from representation of all traces of toil through detailed figuration marked by an optimistically ringing color palette. Quite the opposite, then, of what takes place in Cen Long’s canvases, where drawing gives way to chromatic drafting at first and where a calm intonation predominates, all played out in a refined symphony of blacks, browns and whites. The recurring symbolic elements (such as the cross or the sheep) are taken from Christian iconography, albeit untethered from the original referent, and the joy of the characters is also exemplary because it stems from a suffering that is neither concealed nor sweetened. Moreover, among Cen Long’s Western artistic sources of reference we note the deliberate absence of the currents normally taken as reference by Chinese painters contemporary to him mentioned at the beginning, which are more oriented toward the immediate impact of the image than its subdued revelation to prolonged observation.

To conclude, also very interesting is the story of Crux Art Fundation and its challenge to create international attention around a painter who has always refused to collaborate with commercial realities and is not interested in selling his paintings. The project, as already mentioned, stems from Chairwoman Metra Lin’s 20-year friendship with the artist, whom she met when on behalf of a Japanese publishing house she was sent to China as an interpreter on the occasion of the edition of his illustrations belonging to the graphic series The Old Charcoal Seller, which he created in the late 1980s. Fascinated by his talent and personality, the curator, with no previous experience in the art trade, decided to become custodian of the entire body of his work and began having each painting sent to her as soon as it was finished.

Since retiring from teaching, in fact, Cen Long has been painting in secret because he does not want to show his work in China, where if he were to exhibit in a museum he would have to cede ownership of the works to the government, as Metra tells us. The first step, then, was to find Taiwanese supporters to set up the foundation, which was already an arduous task because of the known tension between the two nations. The next one, the three-year tour currently underway, which has seen the artist featured in prestigious monographic exhibitions in Florence at the Accademia delle Arti del Disegno (March 8 - 30, 2024), in Venice at Palazzo Querini (April 20 - Nov. 24, 2024) in conjunction with the 60th edition of the Biennale Arte, in Bologna at Palazzo Cavazza Isolani (Dec. 12, 2024 - Jan. 12, 2025) and continuing in Rome before touching other European cities and concluding in the United States. At present, there is still no intention to sell (so far only a few minor pieces have been alienated by the foundation, and Cen Long does not yet have an official listing), but the gamble is on getting the painter recognized as a master of international relevance regardless of the established patterns of alliance between gallerists, institutions and collectors that normally preside over an artist’s success. Many ingredients lay in favor of the success of the operation, such as the artist’s compelling biography, the transversal yet recognizable figure of his painting (which in some ways, despite the obvious contextual differences, seems to have many points in common with that of Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, whose already prestigious took off after her participation in the Art Biennale in 2019) and the universality of the emotions she evokes without the need for elaborate exegetical support apparatus.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.