“There is no surer method of escaping from the world than by following art, and no surer method of uniting with the world than through art.” Ipse dixit, or rather: Johann Wolfgang Goethe dixit, as early as three centuries ago, anticipating what Schopenhauer would affirm in his text The World as Will and Representation, namely that art is the only form of liberation from the domination of the will. This was well known by the French poet Verlaine, who in the mid-nineteenth century coined the expression “cursed poet” to designate any artist endowed with genius who, living by a provocative lifestyle, rejects the values of the bourgeois society contemporary with him.

So, as Goethe stated, art as a means of escaping from the world while remaining perfectly in sync with the world itself. This is a paradoxical statement, but as true as ever when one considers how, as visitors, one decides to approach the universe of art (and by art one clearly means any of its expressions, including film and theater).

The visit to a museum represents an important conjuncture for those who approach art and experience it: while on the one hand, in fact, the visitor is enraptured by what he or she encounters as he or she walks through its doors, on the other hand, he or she experiences an opportunity to escape from reality and, very often, from the city bustle that most often one encounters outside the museum context. Between the visitor and the works of art, “synchronic systems” are built, where by synchronization we mean the mechanism of observation-interpretation-interaction that develops between the user of the work and the work itself.

In 2000, the very subject of synchronic systems between the visitor and installations in a museum was the focus of an exhibition entitled Syncro System and dedicated to the works of one of the greatest contemporary talents, Carsten Höller. The 2000 exhibition project for the Fondazione Prada, designated by Höller himself, was intended to be a presentation of “possible worlds” that were meant to visually, intellectually and psychologically stimulate the viewer through a series of labyrinths and sensory pathways. One of Syncro System ’s most famous installations certainly remains Upside Down Mushroom Room (2000), an integral part of the Atlas project since 2018, housed at the Torre, the new exhibition extension of the Fondazione Prada in Milan, designed by Rem Koolhaas’ architecture firm OMA and inaugurated two years ago.

|

| Portrait of Carsten Höller. Ph. Credit Brigitte Lacombe. Courtesy Gagosian |

|

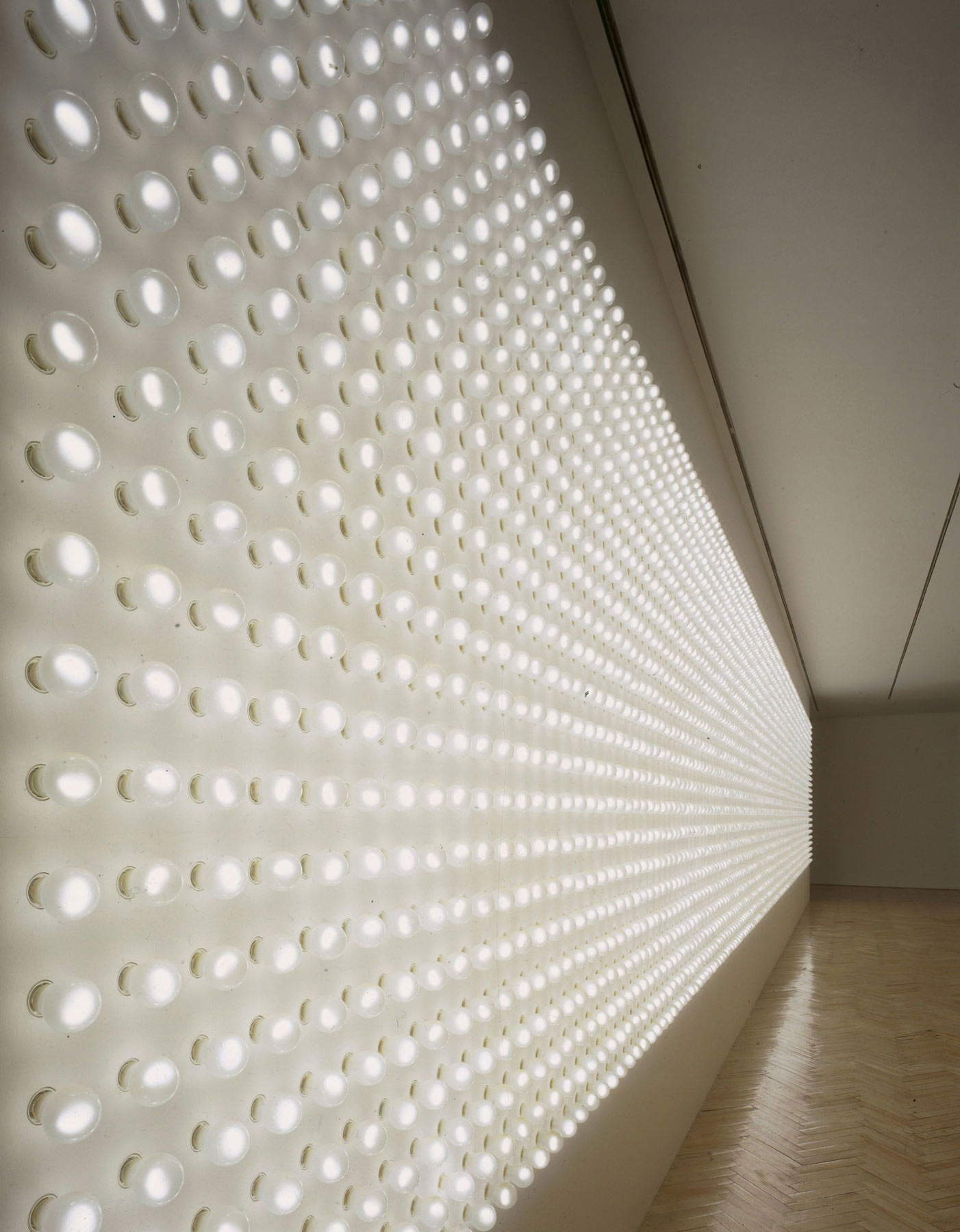

| Carsten Höller, Upside Down Mushroom Room (2018; mixed media; Milan, Fondazione Prada). Ph. Credit Delfino Sisto Legnani and Marco Cappelletti. Courtesy Fondazione Prada |

|

| Carsten Höller, Upside Down Mushroom Room (2018; mixed media; Milan, Fondazione Prada). Ph. Credit Delfino Sisto Legnani and Marco Cappelletti. Courtesy Fondazione Prada |

In a completely neutral exhibition space, the installation features a series of mushrooms (of different sizes and shapes) whose hats and foils are placed upside down, while the stem is the part anchored to the ceiling. This artist’s interest in mushrooms is almost contemporary with the beginning of his artistic activity. In fact, the first mushroom sculptures date back to 1994. Carsten Höller’s choice of the type of mushroom is not causal: it is the dreaded amanita muscaria, the most famous mushroom of the entire mycological flora, but also the most dangerous as it is the most poisonous, as well as the one that has the most repercussions on the human psyche. Certainly, Höller’s choice is intentional: theamanita muscaria is part of our imaginary baggage, also present in Disney fairy tales and therefore known from an early age. The artist’s choice is, therefore, well aimed right from the start: he immediately wants to activate that synchronic mechanism mentioned earlier, that is, one that involves observing the work, interpreting it and interacting with it.

“When you see the world upside down, you are observing the real world,” the artist states. It questions, then, what is the correct view of the world As in Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland (1865), in the more recent Christian Nolan-scripted film Inception (2010), or as in the more recent Netflix TV series Stranger Things (2016), the nature of human perception and self-knowledge occupy a key role in the artist’s installations. Surprise, sensory mechanisms and psychophysical stimuli serve Höller to investigate the new frontiers of human perception and existence, producing surprising and unusual reactions, especially psycho-emotional ones, in the visitor. Höller accomplishes this by means of a scientific criterion and rigor derived precisely from his professional training.

In fact, born in Brussels in 1961, Höller studied agricultural entomology at the University of Kiel where he even earned his doctorate in 1988 with a research on insect communication. Paradoxically, just after he finished his doctorate, he decided to give up science as a profession and use what he had studied over the years to make his conceptual sculpture-installations that, to date, have become famous and exhibited worldwide. The interaction between visitor and artwork is the focal point of his artistic research: the installations come to life and are complete only at the moment when the visitor interacts with them. Being a scientist before being an artist, the investigations he carries out through his sculpture-installations aim at the knowledge of human logic and the insinuation of doubt about the past, present and future of his interlocutors. Höller’s works involve various fields of human professional activity: indeed, they cross the boundaries of the botanist, the zoologist, the psychologist, the pharmacist, the optician, and the architect. A three hundred and sixty-degree work that also leads to a new discussion of the boundaries of what can be considered contemporary art, especially in relation to the space that houses the works, namely the contemporary art museum.

Famous all over the world are Carsten Höller’s sculpture-slides. Certainly one of the most famous is Test Site at the Tate Modern in London, installed in 2006 and repurposed in other countries such as Germany (Bundeskunsthalle in Bonn), Italy (Palazzo Strozzi), Finland and the United States. For Test Site, too, the interaction between the visitor, the work and the space that houses it remains central to the artist’s artistic research. The installation consisted of five whirlwind-slides connecting the upper floors of the Tate to the ground floor. Slides are considered playful objects for children, rarely used by adults except in other contexts, such as an amusement park or aquafan. Decontextualized from their playful environment, these whirlwind-slides become objects that are at the service of museum visitors, who can freely experience them. From this sensory experience spring surprising, quite intense psychic and physical reactions, which are precisely the object of study of our scientist-artist. Höller believes that the art object itself has no intrinsic nature unless it is related to its spatial and, above all, human context. The art world is, therefore, constituted by a system of interrelationships or, if we want to go back to the beginning of this article, to a series of synchronic systems between user and artwork.

|

| Carsten Höller, Test Site (2006). Installation view, London, Tate Modern |

|

| Carsten Höller, Test Site (2018). Installation view, Bonn, Bundeskunsthalle |

|

| Carsten Höller, The Florence Experiment (2018). Installation view, Florence, Palazzo Strozzi. Ph. Credit Martino Margheri. Courtesy Palazzo Strozzi. |

|

| Carsten Höller, The Florence Experiment (2018). Installation view, Florence, Palazzo Strozzi. Ph. Credit Martino Margheri. Courtesy Palazzo Strozzi |

Höller’s important scientific background emerges not only from his interest in questions related to logic and human perception. The animal world, in addition to the mycological world discussed earlier, plays a decisive role within his investigative processes. For documenta X in Kassel, in 1997, Höller presented, together with the famous German artist (and his partner) Rosemarie Trockel, the famous installation A House for Pigs and People, a project that sought to bring the animal subject to the stage of one of the world’s most important art events. The two artists’ research, as they themselves explain, stemmed from a desire to understand whether the use, whether possible or not, of certain foods (plants or animals) having a symbolic value (in this case, just think of the consumption of pork for some religions) can also semantically affect the human being, that is, whether this symbolism is also projected by osmosis onto the consumer. The interest was also clearly centered on the religious and political question in reference to whether or not to decide, whether or not to subjugate certain social classes, whether or not to prohibit the consumption of a certain food for religious, magical, ethical or other issues (if one thinks about it, it turns out to be quite a current issue even in today’s Italy). In a rectangular concrete structure, a sheet of glass separated the sections of the house into two: pigs on one side, people on the other. The view was deliberately unidirectional: only the people were able to observe the pigs, but not vice versa. The pig was chosen because it had always been a species domesticated by humans, considered primarily as meat for slaughter.

The division (and interaction) between the animal and human worlds was also the focus of SOMA, the crazy 2010 installation presented at the Hamburger Bahnhof, the Berlin Museum of Contemporary Art in Germany. In one of the world’s most important contemporary art contexts, Höller offered visitors the chance to sleep on a suspended bed in the company of twelve (live!) reindeer, canaries, mice, flies, and some giant mushrooms, transforming the art installation into a veritable psychedelic vision with the aim, not only to surprise the visitor but, once again, to be able to study its effects on human perception. The title SOMA refers to the Sanskrit term for the juice made from a plant used for sacrificial offerings in the Vedic religion. The hallucinogenic drink leads to a very special state of mind for the drinker: it seems, in fact, to access enlightenment, to contact with the deeper self. Not only that: it seems that the sacred juice also has therapeutic properties de exceptional magical virtues (healing diseases, giving fertility and happiness, improving perceptual qualities). SOMA, however, is also the term known in Nordic countries for the drink made from the mushroom amanita muscaria (the same as the Prada installation). Theamanita was apparently sought after by the Choriacs, an indigenous population in the far east of Russia, and they were willing to pay a very high price for it: one mushroom alone was worth an entire reindeer. Reindeer, moreover, feed on the mushroom, and their urine, which had retained the hallucinogenic principle, was stored and used for the same purposes as the mushroom. In the face of what has been explained, the artist’s experimentation, namely to induce the visitor to the Hamburger Bahnhof to relive the same hallucinogenic effects of Soma for one night, seems evident.

|

| Carsten Höller, Soma (2010). Installation view, Berlin, Hamburger Bahnhof Museum für Gegenwart. |

|

| Carsten Höller, Ein Haus für Schweine und Menschen (A house for pigs and people) (1997). Installation view, Kassel, documenta X. Ph. Credit Bernhard Rüffert. © documenta Archiv. |

|

| Carsten Höller, Lightwall (2000). Installation view, Milan, Fondazione Prada. Ph. Credit Attilio Maranzano. Courtesy Fondazione Prada. |

The study of optical and acoustic hallucinations was the underlying theme of the Lightwall series of installations, created between 2000 and 2007. In this series of installations, Höller envisioned a wall consisting of nine panels, in which each panel features a grid of light bulbs that flash on and off intermittently, at a frequency ompressed between seven and twelve herz, combined with a stereo signal that clicks between two audio speakers. The resulting effect is one of disorientation for the visitor, who experiences fields of light and sound that induce an altered perception of themselves and their surroundings, including sound aspects.

Because of his crossing the boundary between science and art, Carsten Höller has attracted the interest of the largest international contemporary art institutions: his experiments-installations have been and are being exhibited in important contexts, such as the Moderna Museet in Stockholm, the Prada Foundation in Milan, the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art, and the New Museum in New York, to name a few. His Upside Down world enchants and astonishes museum visitors because of the questions he unceasingly keeps asking, which are related precisely to the world of self-perception and the reality in which we live. How do we know, in fact, that the world we live in is the correct one? How can we know with certainty where the good is, where the bad is, what is right and what is wrong? The wonder and beauty of Höller’s installations is precisely in insinuating the doubt of reality the moment the visitor becomes part of that synchronic system with the artwork mentioned in the opening. It is about crossing the boundaries of the possible, the human universe and knowledge of the latter to instate the sacrosanct benefit of doubt, which is fundamental in a democratic society as it leads to reasoning about the reality we are being told by the mass media. After all, as Socrates said, the philosopher (in the Greek world, the person who held knowledge) was the one who knew that he did not know.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.