At a time when being a female artist was already somewhat complicated and unusual, given that the artistic scene was mostly dominated by the male gender, being an artist and a sculptor in particular meant being a white fly, a case apart that certainly deserves special attention. Even if even today the life and works of Carmela Adani (Modena, 1899 - Correggio, 1965) are known just within the restricted area of her area of origin, the lower Reggio Emilia area, mainly due to the research of Renza Bolognesi and the monographic volume edited by Giuseppe Adani, the artist’s nephew, and Gastone Tamagnini published in 1975 by the Cassa di Risparmio di Reggio Emilia, as well as the exhibition of her plastic and graphic works held in the same year in Reggio Emilia and then in Correggio.

The case of Carmela Adani, Modenese by birth but Correggese in soul, deserves to be known throughout the country in order to give her the recognition that in life she partly obtained but that post mortem unfortunately ended up in oblivion. Testimonies of her sculpture can in fact be found in so many churches in Reggio Emilia and the province: they are works of extraordinary quality, so much so that it seems impossible that their creator should have been forgotten in this way, both for her technical gifts and for her own history. Yet this is what happened.

“Being a woman is my misfortune and my fortune,” she had said. “Misfortune, because in a woman artist people are led to believe less than in a man; fortune, because as a woman I can add something more to my works than a man who has the same possibilities as me.” Indeed, as has already been pointed out, undertaking artistic activity for a woman in the first half of the twentieth century (in fact, she was born in Modena on November 7, 1899, and died in Correggio on November 19, 1965) was difficult both because of the possibilities of study as well as for the often ingrained prejudice that women had to devote themselves exclusively to the domestic environment and the education of their children, thus abandoning all intellectual aspirations and any predisposition that had to do with manual and creative skills. Moreover, it seemed truly incredible that a petite, modest and humble girl such as Carmela Adani was able to work with such skill and dexterity, alone with hammer and chisel, marble, a hard and heavy material par excellence. Yet if she had mastered the way she could master marble, she probably would have become much more famous and her work better recognized,

Hers was an innate gift: already as a child she frequented the workshop of her father, Primo Adani, who by trade was a marble craftsman , as marble craftsmen were her ancestors (an aspect not to be underestimated for her artistic vein), and already there, in fact, her inclinations for drawing and sculpture had already been noted. His talents and passion, however, were complemented by constant study and exercise to which he devoted himself for as long as he lived. Her art looked to tradition and classical antiquity, but she complemented this with a careful study of life, attested by a multitude of drawings of all kinds, and in particular a careful exercise of portraiture. She was especially fascinated by the art of the Florentine Renaissance, and it was to Florence that Adani moved in 1922, where she had the honor of becoming a pupil of Amalia Duprè, daughter of the famous sculptor Giovanni, after the latter had the opportunity to see some of her work. She then managed to enter theAccademia di Belle Arti in Florence, where she had Giuseppe Graziosi as her teacher, but here she also got to know artists such as Pietro Annigoni, Felice Carena and all the masters associated with the Florentine academic world of that time. She was one of the first women in Italy to graduate in architectural drawing. In fact, she would stop on the streets of the Tuscan capital to draw any subject having to do with art: architecture, views, foreshortenings, decorative motifs, sculptures and museum paintings, filling a large amount of sheets. A passion and curiosity that later resulted in his great ability to range from one genre to another, from monumental statuary to busts, from altarpieces to cemetery headstones, from sacred vessels to bas-reliefs. He also did very well in architecture: in fact, he contributed to the construction and remodeling of many buildings; he even designed and planned structural elements of buildings that were later constructed by his brother Mario, a missionary in Africa and builder of churches, schools, and hospitals. However, it was from his Florentine and academic experience that he understood his greatest inclination: the representation of the human figure as the highest expression of feeling. Indeed, her sculptures show her great sensitivity, as only a woman can make visible, and the human figures depicted become vehicles of the psychological and inner dimension. Very devout and religious, her works almost always reveal a sacred dimension, which is why they are mostly made for churches or religious places, and always with an extraordinary use of light, which reflects and creeps between the marble details.

Among her skills, one counts being the best creator of the Ars Canusina on marble, a genre of artistic craftsmanship that evoked the period of Matilda of Canossa’s rule, an extremely pivotal era for this area of Italy. Carried from paper to leather, to canvases and ceramics, the decorative motifs found in the churches of the various localities in the province of Reggio Emilia and in the miniatures of the Matildic codices had Adani as their greatest exponent of transpositions on marble.

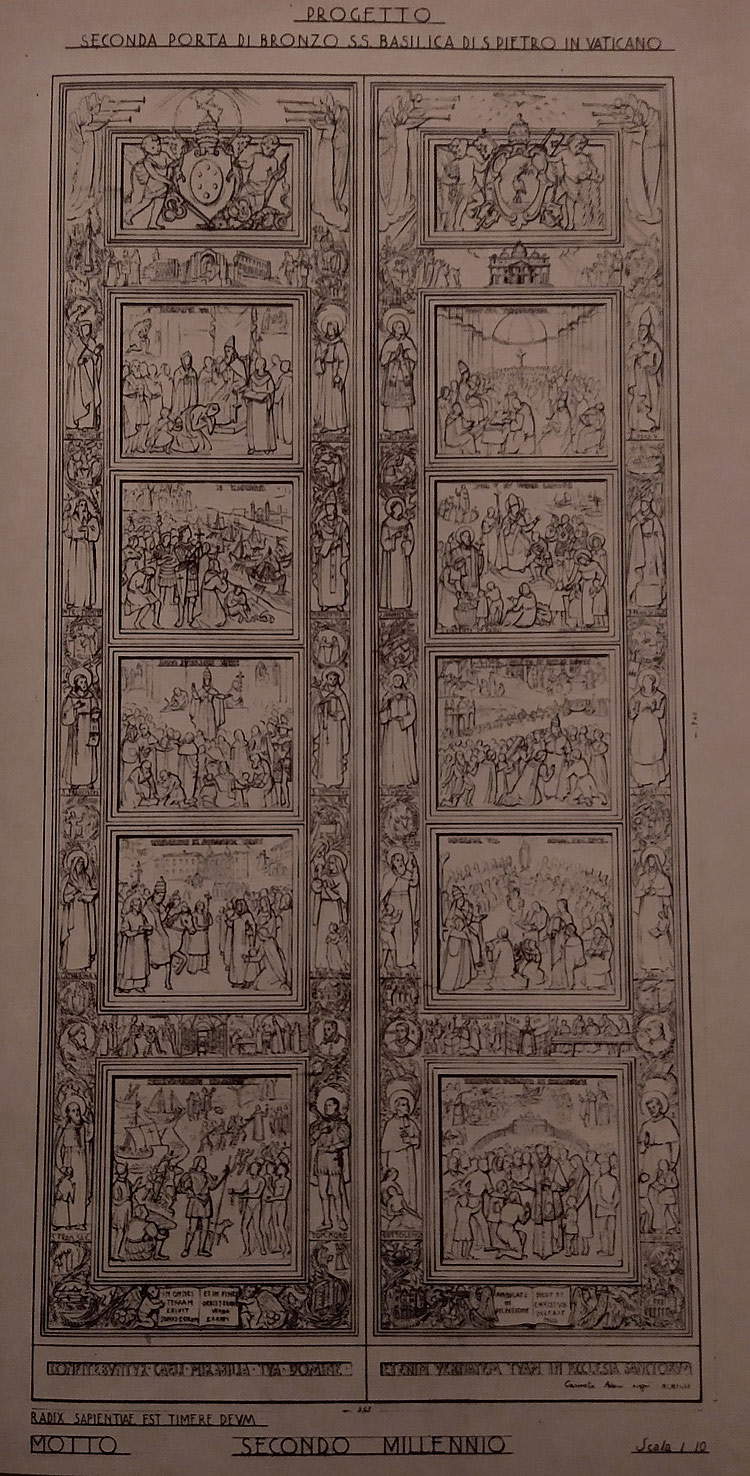

In 1947 she participated, under pressure of persuasion, in the competition for the new bronze doors of St. Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican: she was the only woman among about eighty sculptors from around the world, and the commission awarded her a silver medal as a distinction. It was her extreme modesty that prevented her from making a name for herself even outside her own territory: consider that she devoted herself to the competition for the doors of St. Peter’s at night, so as not to spend hours of her usual daytime work on what she considered an “artistic escapism.” She loved working in her Correggio studio on Via Carlo V, located a short distance from the house that was, between the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the home of Antonio Allegri, the illustrious painter who took his name from her town, and above all she was attached to her land and her family, which is why, after the Florentine interlude, she remained forever in her Correggio, where she was nevertheless active in public life. A plaque in the crypt of the town’s Basilica remembers her as a sculptor who “sweetly sculpted statues that breathed life, with which she enriched temples and in our lands and those far away.”

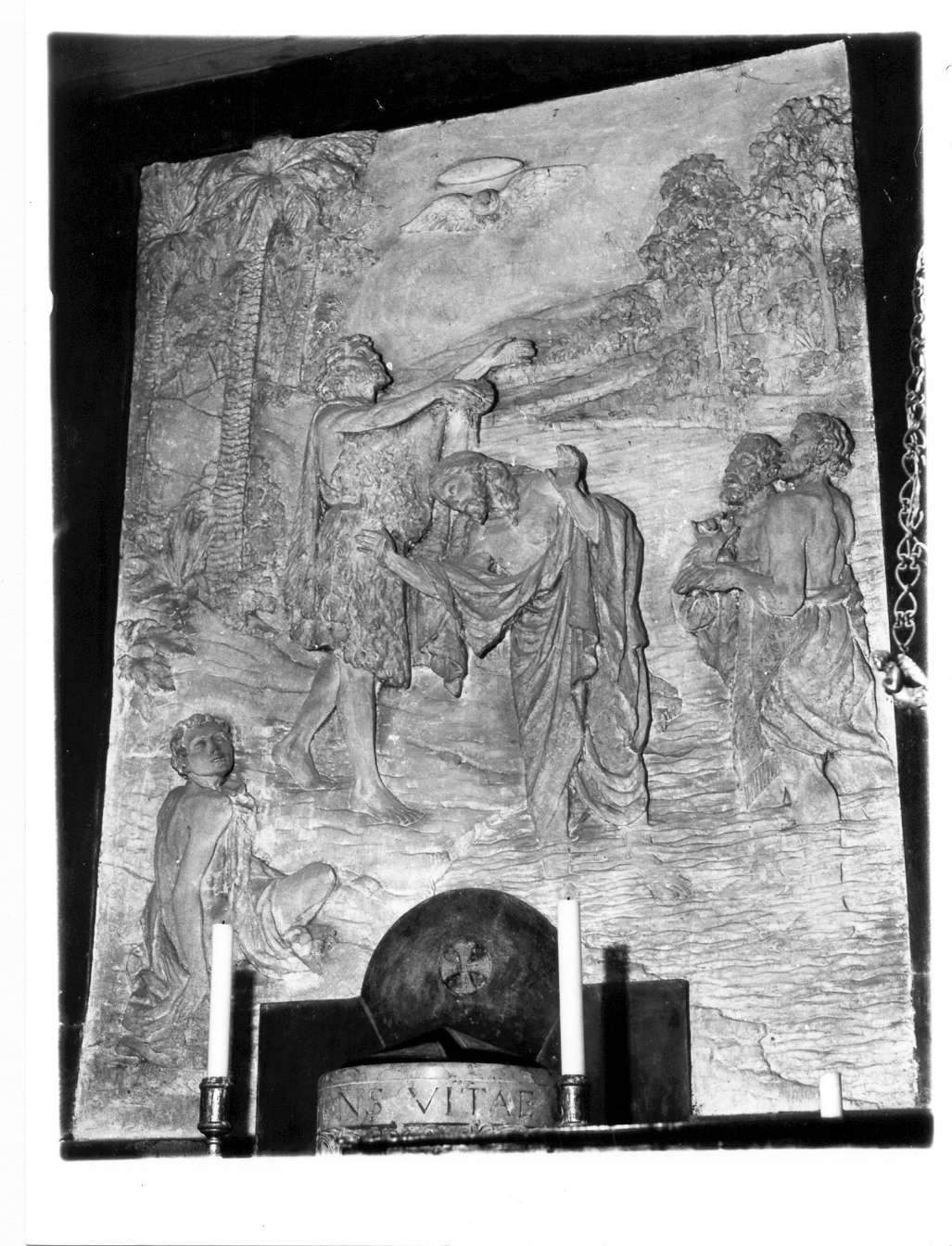

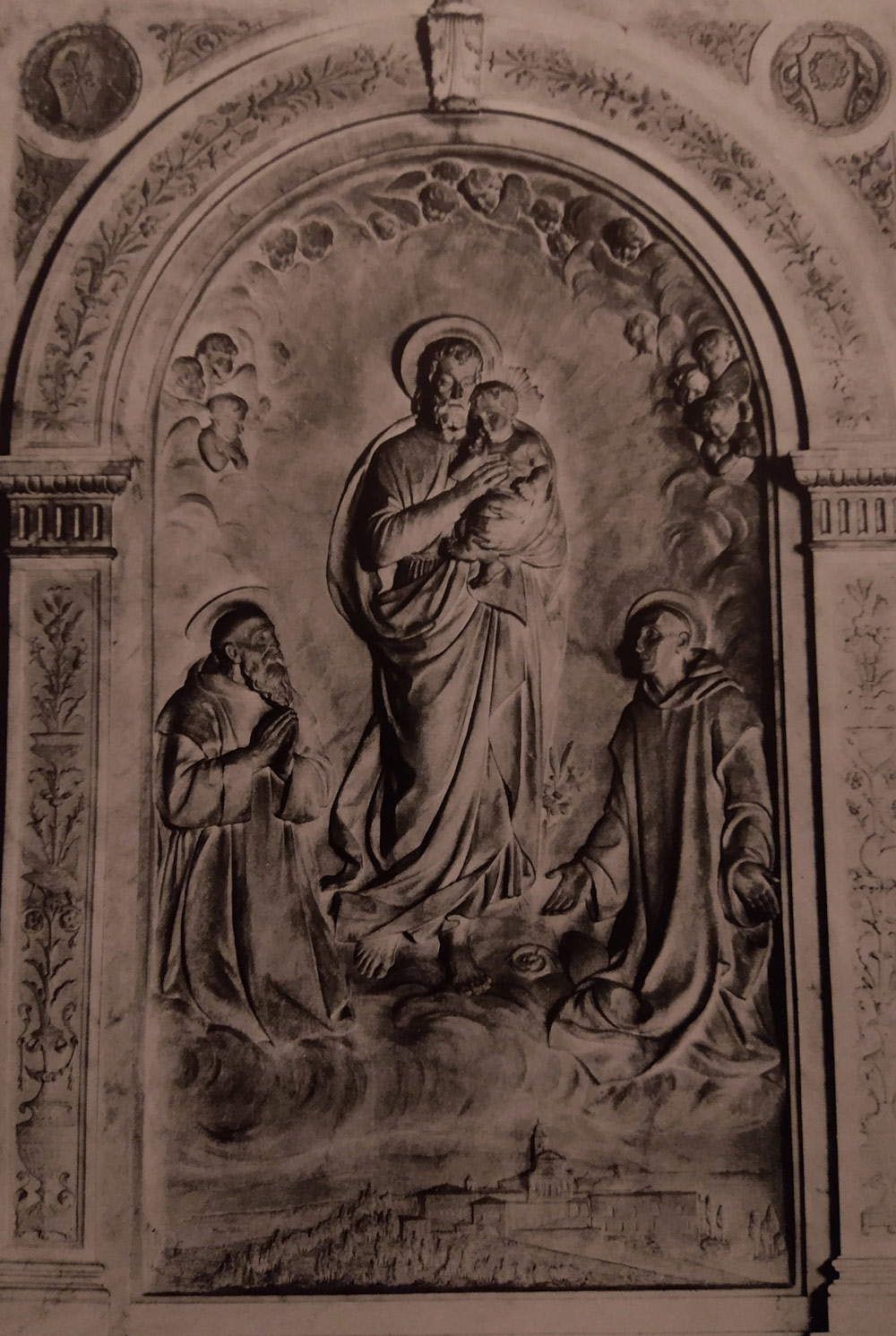

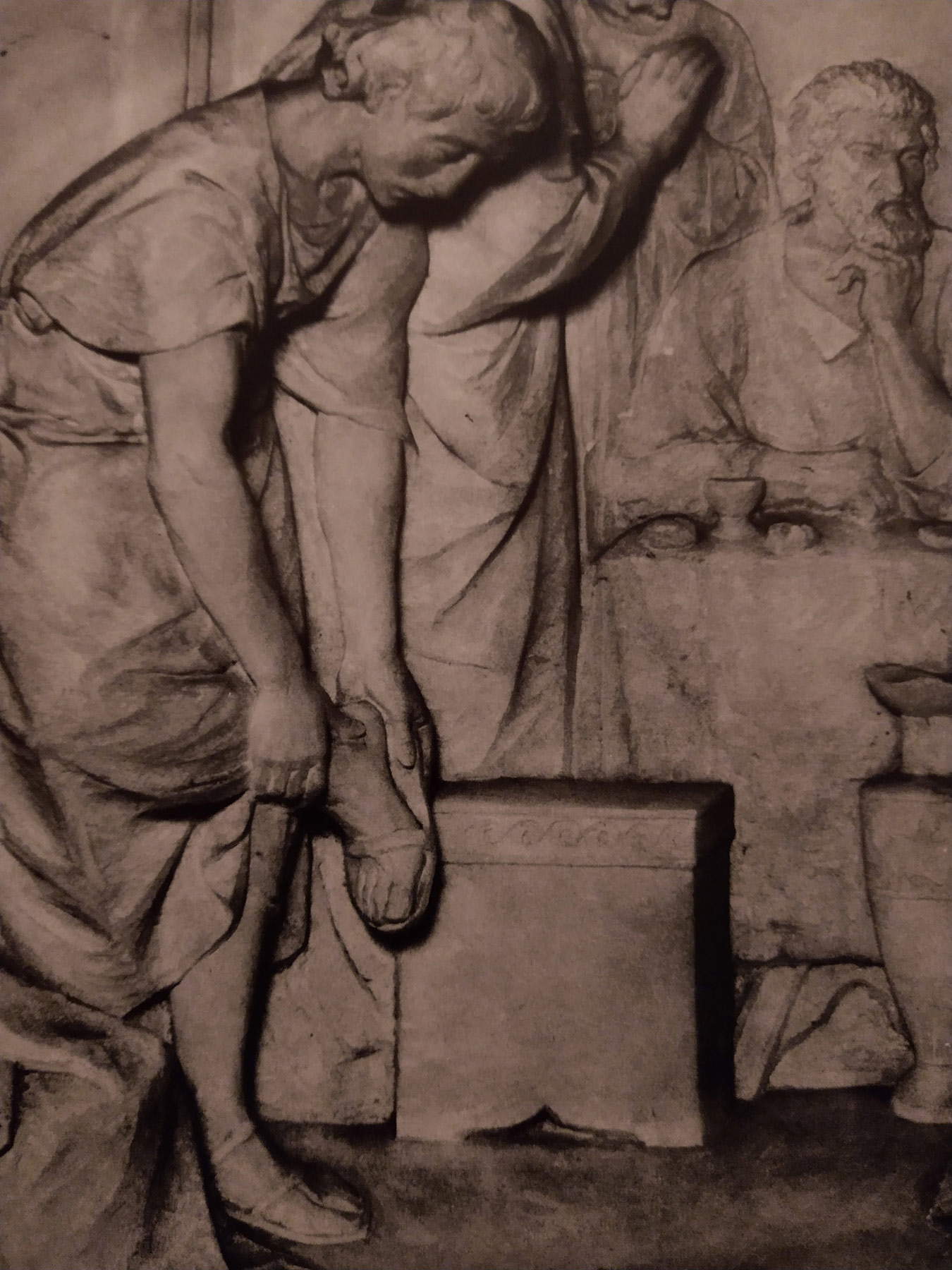

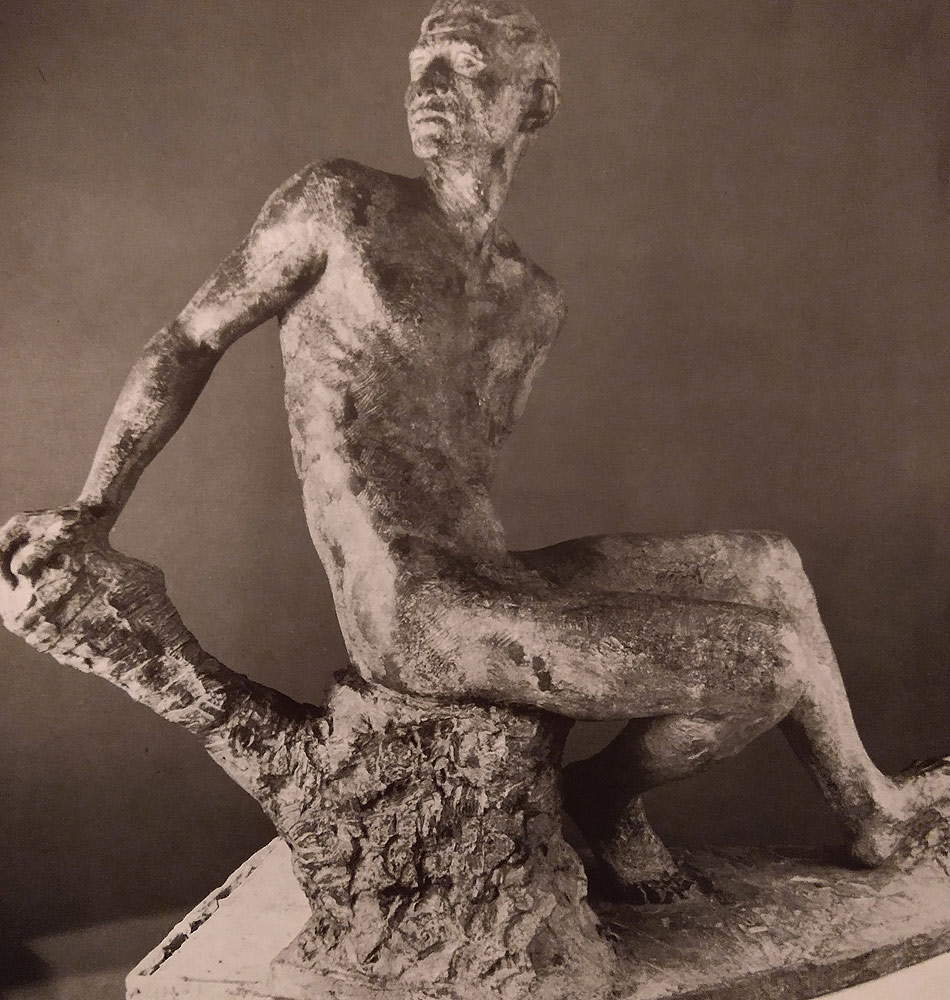

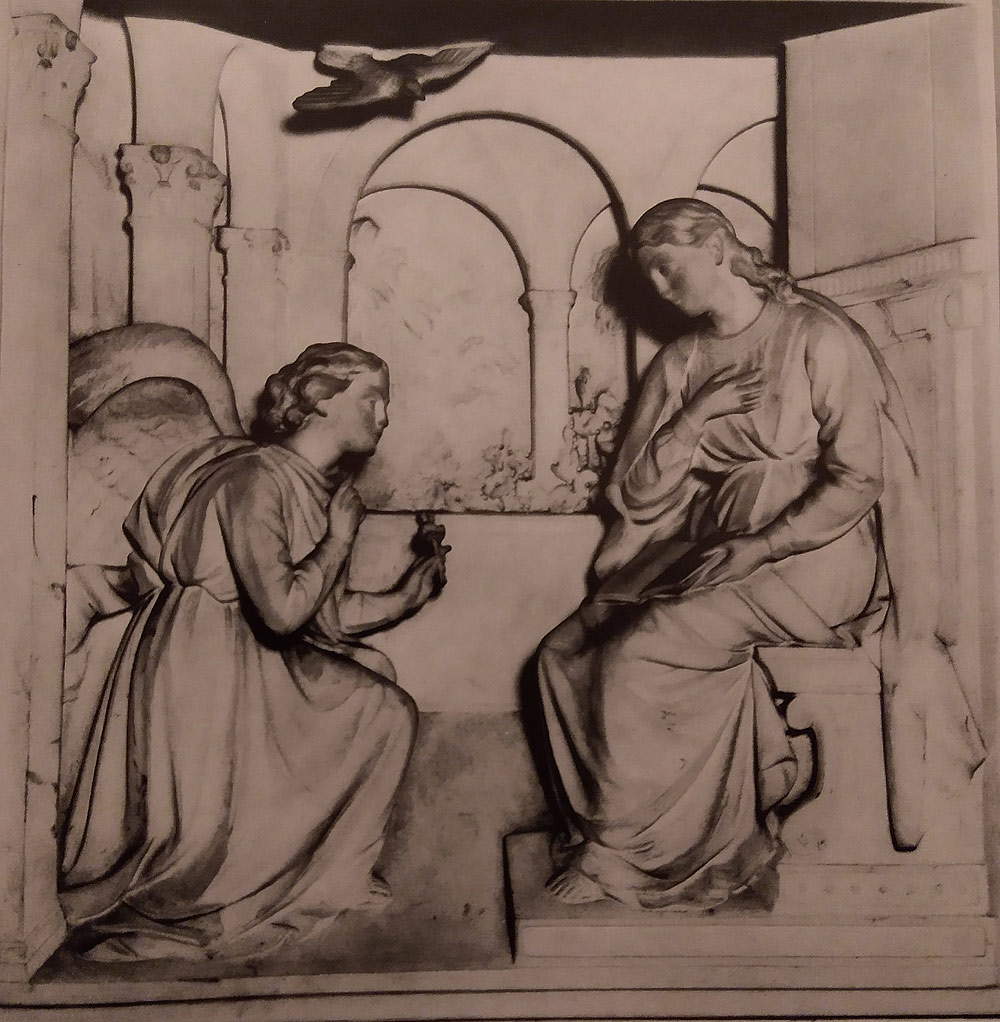

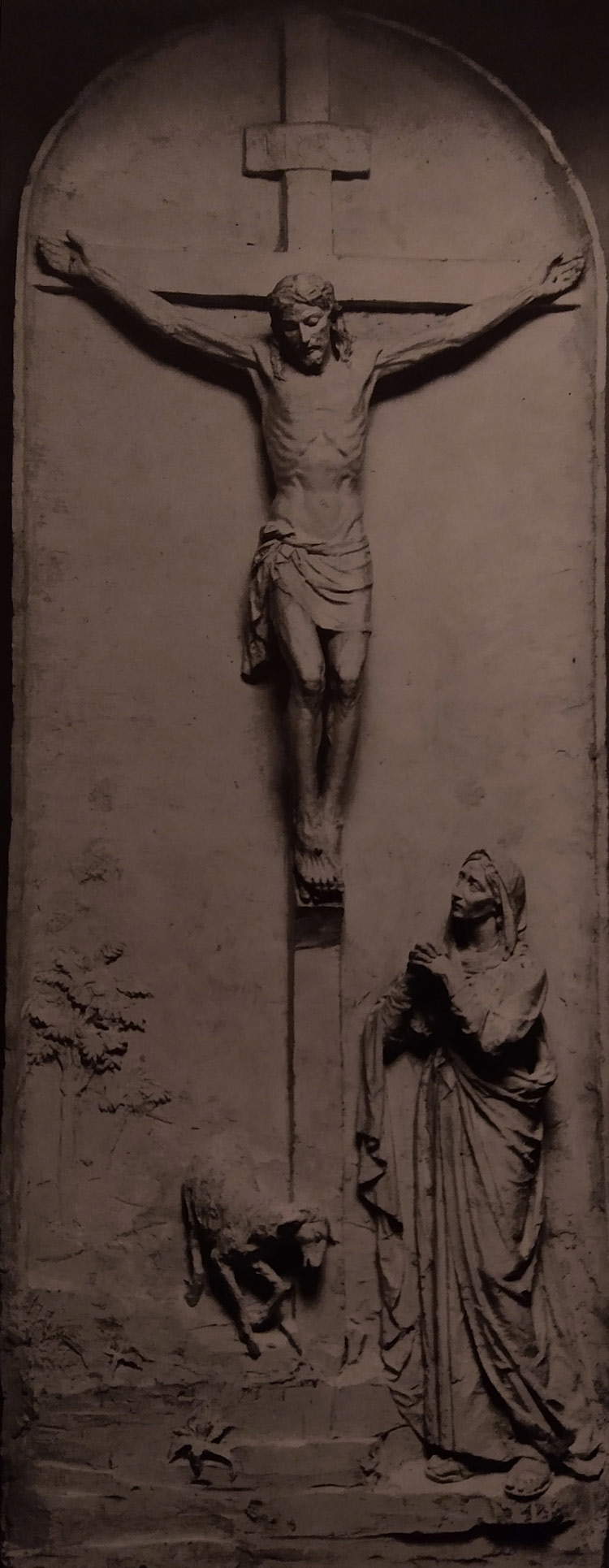

Among her most significant early works, she made directly with the chisel, without a clay model, the marble altarpiece depicting the Baptism of Jesus for the Pieve di Fosdondo, the composition of which shows monumental figures with soft draperies immersed in a landscape that celebrates the contemplative dimension; particularly interesting is the figure of a seated nude youth in which the sculptor skillfully rendered the twisting of the body. From 1931 is the large marble altarpiece for the Certosa in Florence, in which Adani brought together the naturalistic and luministic experiences of the early Florentine period: in the center is Saint Joseph holding the baby Jesus between the Blessed Bernard and Brunone, and below she depicted one of the most beautiful views of the Florentine landscape in twentieth-century sculpture. He then made the Chapel of the Blessed Sacrament in the Basilica of Saints Michael and Quirino in Correggio, and in particular the scene of the Washing of the Feet, the centerpiece of the chapel’s entire design. From the same period are the terracotta portrait of Giovanni Duprè, Amalia’s father, and the pictorial portrait of his sister Gilda Adani. He then executed nudes, such as the Large Manly Nude, the Source Nude, and The Outstretched. Also splendid is the Triptych of the Basilica of San Quirino, where in the three niches appear respectively St. Michael with the dragon, St. Quirino the bishop, and St. Raphael with Tobiolo accompanied by cute little dog: three large monumental figures sculpted with a mosaic background. Also worth mentioning is the highly refined Annunciation in Reggio Emilia Cathedral and, among his best-known masterpieces, the 1956 marble altarpiece depicting the famous Canossa episode in the Regina Pacis church in Reggio Emilia. The altarpiece is in one of the few altars dedicated to Pope Gregory VII: of great refinement, Henry IV can be recognized kneeling and barefoot, the pontiff enthroned, Matilda of Canossa, and the abbot of Cluny. Belonging instead to the last period of the artist’s life are the high relief of the Azzali Crucifixion and the bronze Christ of Baragalla, still placed on a trellis: the latter constitutes one of the few representations of the iconography of the Sacred Heart, which Adani masterfully executed.

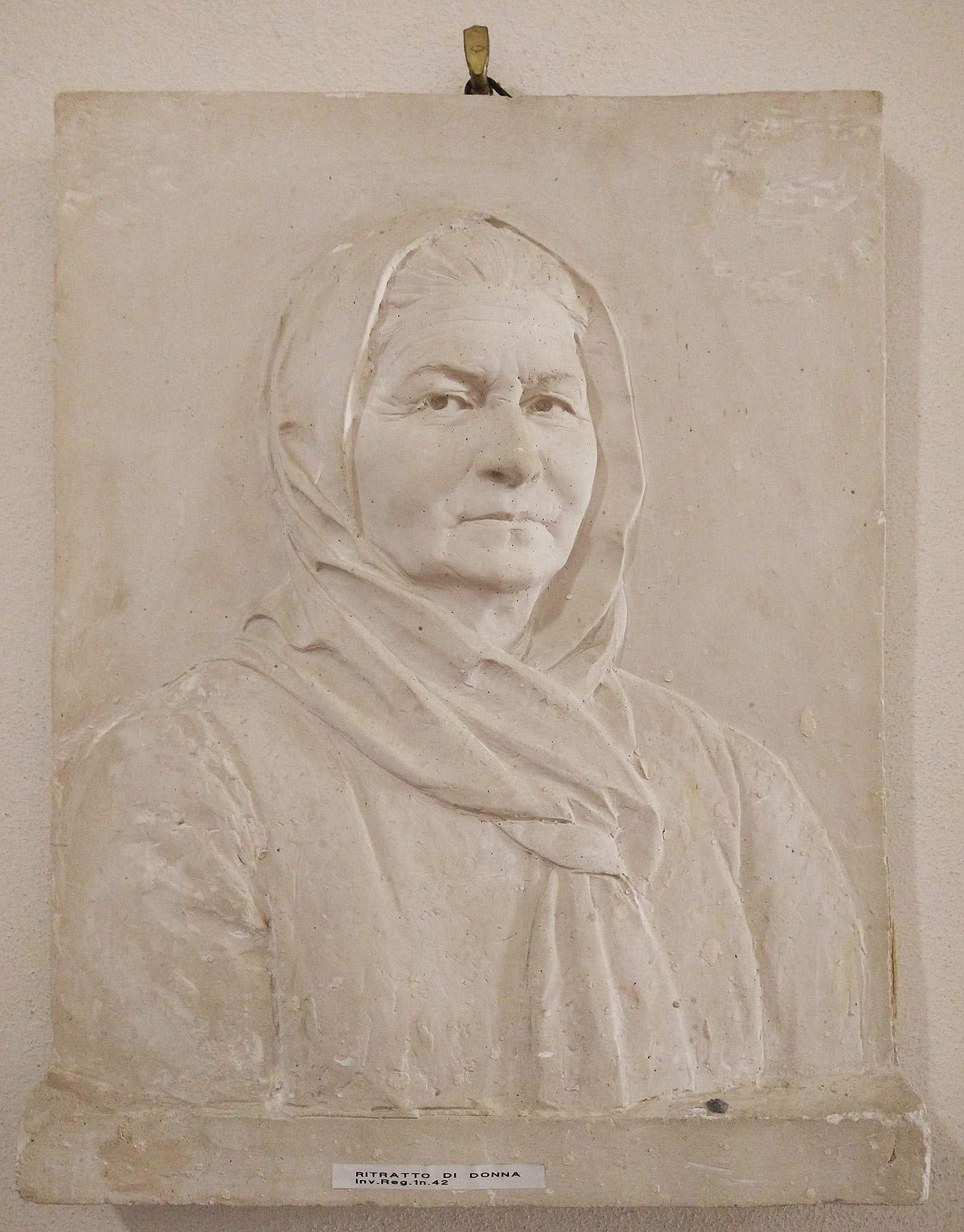

Today Carmela Adani’s Gipsoteca is located in the premises of the Liceo Classico “Rinaldo Corso” in Correggio since it was donated to the institution. In 2000, in fact, the former San Francesco convent in Correggio was being restored for use by the high school, which was left without a seat after the 1996 earthquake. By September 2000, work on the ground floor and part of the second floor of the former convent should have been finished to house the school here. During the work, restoration director Gian Andrea Ferrari had the opportunity to meet Professor Giuseppe Adani, the sculptor’s grandson and custodian of her gipsoteca, who had been pressing the City of Correggio for years for a suitable home for the gipsoteca in order to be able to donate it to the townspeople. An opportunity to make the artist’s sculptural heritage known to all. And what better venue than the Liceo, where to this day the long corridors of the ground floor still house the gipsoteca? The school already possessed a large collection of ancient scientific instruments, a collection of ancient engravings and maps, and an important library with rare texts from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. These were then joined by the Adani’s gypsoteca: when the agreement was signed, the most significant part of the sculptures had already been moved to the new location of the high school in June 2000. Thus the artist’s sculptures and plaster models, mostly related to religious themes dear to her heart, have found a permanent home here. Examples are the plaster model of the St. Joseph Altarpiece, the marble original of which is in the Certosa del Galluzzo in Florence, the model of the Supper at Emmaus, the original of which forms the frontal of the high altar in the sanctuary of the Madonna dell’Olmo in Montecchio, the model of the Triptych of St. Quirino (the original in the crypt of the church of St. Quirino in Correggio). Also, the plaster model of theAltar of the Blessed Sacrament of the church of San Quirino, the model of the high relief depicting Christ and the Wise Virgins (the original in the Monumental Cemetery in Verona), the model of the high relief with the Miracle of the Mula of St. Anthony of Padua (the original forms the frontal of the high altar of the church of San Giovanni Evangelista in Reggio Emilia), the model of the Bust of Bishop Mons. Brettoni, the original of which is in the Cathedral of Reggio Emilia, the model of St. Constance. There is also the plaster model of the Portrait of Amalia Duprè; and then the bas-relief models of the Twelve Apostles (the original in the sanctuary of the Madonna dell’Olmo in Montecchio), the Portrait of teacher Erminia Valli, the Bust of Msgr. Leone Tondelli (original in the Cathedral of Reggio Emilia) and the Portrait of Dr. Giovanni Recordati.

The younger generations (and not only) thus have the opportunity to be in daily contact with the works of this artist, who unfortunately remained known almost exclusively at the local level, but who could have become, due to her great skill and strong sensibility, one of the most significant artists of the early twentieth century at the national level. Who knows if in the future, with proper exhibition and study opportunities, Carmela Adani will achieve greater recognition. We hope so.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.