Caravaggio or Spadarino? The story of the "Narcissus" in the National Gallery of Ancient Art at Palazzo Barberini

The Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica at Palazzo Barberini in Rome houses one of our richest and most interesting collections of Caravaggesque paintings, works, that is, made in the seventeenth century by different artists influenced in various ways by the powerful and innovative pictorial language of Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (Milan, 1571 - Porto Ercole, 1610). The same museum also houses three well-known canvases, presented to the public as originals by the Lombard painter: Judith and Holofernes, St. Francis in Meditation and Narcissus. However, if regarding the first work there have never existed any consistent doubts about its authorship, more complex are the attributional vicissitudes of the other two. In particular, as we shall see, an extremely articulate debate has developed among scholars around the painting depicting the mythological hero.

The well-known and tragic story of Narcissus, which perhaps more than any other from the ancient world has marked our culture, is reported by Greek and Roman authors, including Ovid who recounts it in his Metamorphoses.

The boy, son of the river Cephysus and the nymph Liriope, possesses an extraordinary beauty that attracts numerous lovers, all of whom he rejects. Among them is the nymph Echo who, unrequited, is consumed by sorrow until all that remains of her is her voice. Then the goddess Nemesis, invoked by one of Narcissus’ unhappy suitors, intervenes and decides to punish the latter by causing him the same suffering he inflicted. So one day, tired after hunting, in a dense forest, the young man sees a spring of crystal-clear water and approaches it to drink, but “as he tries to quench his thirst, another grows within him,” Ovid writes. In fact, escorting its reflected image, he falls in love with it: he “falls in love with an illusion that has no body, thinking that it is body what is nothing but wave.” After long and vainly trying to touch the figure that appeared on the surface of the water, Narcissus realizes his condition, despairs, and eventually dies overcome with grief (in Greek versions he dies by suicide by piercing himself with a sword or drowned in an attempt to reach his image). When the Naiads arrive at the spring to perform the funeral rites, they find a flower in place of his body.

Needless to say, there have been endless pictorial transpositions of the myth over the centuries. The Palazzo Barberini canvas, however, presents an entirely original setting of the scene: the entire story is condensed into the description of the vain attempt of Narcissus, in seventeenth-century clothing, kneeling and with one hand in the water, to grasp his reflected image. Disappearing are the details to which artists previously, in the same years, and even later, had resorted and would resort to in recounting the myth. We do not see Echo, nor the flowers named after Narcissus, nor the deer, the dog or the bow (attributes of the young hunter), nor even the lush wooded landscape, which is hidden by the half-light, from which only the two images of the boy emerge, one on top of the other, in a ’playing card’ construction.

|

| Caravaggio or Giovanni Antonio Galli called the Spadarino, Narcissus (1597-1599 or 1645; oil on canvas, 112 x 92 cm; Rome, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica di Palazzo Barberini) |

If we look, for example, at the fresco of the same subject executed by Domenichino (Domenico Zampieri; Bologna, 1581 - Naples, 1641), now in the Palazzo Farnese, we see Narcissus bending over the water in a position quite similar to that assumed by the character in the seventeenth-century canvas, but inserted, here, in a wide and bright landscape setting, of which a walled palace is also a part. Incidentally, Domenichino executed this work at the beginning of the 17th century, close to the years in which the Barberini Gallery painting is placed by the majority of scholars who recognize it as Caravaggio, a fact that has led many to hypothesize a direct influence of the canvas on the fresco, at least with regard to the posture of Narcissus. An influence that has been interpreted in the opposite direction by those, such as Gianni Papi, who have proposed a much later dating of the painting.

An important cue for the conception of the figure of Narcissus, at any rate, was certainly provided to both of the seventeenth-century paintings mentioned (as well as to many others) by the engravings that accompany the numerous and very popular sixteenth-century editions, mainly in the vernacular but also in Latin, of Ovid’s Metamorphoses . In these engravings, the boy is portrayed with his arms outstretched and his hands on the ground, kneeling in front of the pool of water, on which we catch a glimpse of his reflection, exactly as in the Farnese fresco and the painting in Palazzo Barberini. However, almost always, such printed illustrations report the entire story of Narcissus, or at least some of his most important moments, with a paratactic construction of the depiction: that is, the protagonist is portrayed in several successive moments of the story, depicted around or behind his figure bent over the water, placed in the center. Consider the engraving decorating the 1505 text Metamorphoseos edited by humanist Raffaele Regio (Bergamo, c. 1440 - Venice, 1520), in which an unknown artist structured his graphic elaboration of the myth, proceeding from the left, where are Narcissus and Echo clinging to him, to the right, where the body of the now dead hero is seen lying down, passing through the center where the main scene is placed, with the young man, kneeling, contemplating his reflection at the spring.

In another engraving, dating from the mid-sixteenth century and made by Tommaso Barlacchi (active in Rome from 1541 to 1550), on the other hand, depicts the boy alone, in front of the pool of water, with his knee in full light and a tuft of hair in evidence, both very similar to those of the protagonist of the Barberini canvas, of which, in the opinion of many scholars, this graphic work constitutes an important model.

Thus, the Rome painting, although insertable into a long figurative tradition as far as the definition of Narcissus is concerned (his posture, the presence of the reflection), represents a unicum, because in it a sharp and entirely new synthesis is made, concentrating the character’s tragic journey in a silent overlay of foreground images, revealed by a flash of light. And it is precisely the scope of the iconographic innovation and the expressive power of the painting that have always been among the main arguments advanced in favor of its attribution to Caravaggio.

The querelle over the author’s identity, which has been going on for decades, originated mainly from theabsence of ancient sources that unequivocally mention the painting in question. In 1913, Roberto Longhi, the art historian who was the main architect of Caravaggio’s rediscovery during the last century, saw the painting in Milan in the private collection of his colleague Paolo D’Ancona and, three years later, in his article Gentileschi father and daughter pointed to it as an autograph by Merisi, and then reiterated this conviction several times in the course of his studies. Longhi called the work “one of the most personal inventions” of the great painter, thus first highlighting the importance and originality of the intuition behind it. Later other authoritative scholars, such as Maurizio Marini and Rossella Vodret returned to insist on this point. In particular, Marini, dealing with the other consistent attributive hypothesis, whereby the painting should be attributed to Giovanni Antonio Galli known as lo Spadarino (Rome, 1585 - 1652), stated in his text Caravaggio. Pictor Praestantissimus (upholding it until the last recent reprint) that the painting comes to express a “melancholic lyricism” far removed from Spadarino who “never achieved such, Leonardesque, ’motions of the soul.’” However, this is a conclusion that has not always found adherence among experts. Among those who have disagreed is certainly Papi, who, as we shall see later, is one of the most staunch assertors, precisely, of the assignment of the painting to Galli, and according to whom that “sorrowful sense of human experience” emanating from the “disturbing force of invention” is absolutely compatible with the language of the aforementioned painter. Shortly after Longhi’s discovery, the work was purchased by Basile Khwoschinski, who eventually donated it to the Roman Gallery.

|

| Domenichino, Narcissus (1603-1604; detached fresco, 143 x 267 cm; Rome, Palazzo Farnese) |

|

| Tommaso Barlacchi, Narcissus (1540-1550; engraving). |

In the 1970s Marini, in the monograph Io, Michelangelo da Caravaggio brought to attention the nineteenth-century mention (by Antonino Bertolotti) of a document dating from 1645 authorizing the export from Rome to Savona of a group of works, including a Narcissus by Caravaggio, of the same dimensions as the work in Palazzo Barberini.

In 1989 art historian Rossella Vodret published in its entirety the export license, which she traced to the State Archives in Rome, on which appeared the name and surname of the person who had sent the painting: “Jo.Bap.Ta Valtabel.” Later Marini identified him as Giovanni Battista Valdibella, a member of a Genoese merchant family.

There was, and still is, a lack of certainty that the license in question referred precisely to the Narcissus now preserved in Rome. However, it seemed that with the rediscovery of the document, what Longhi had argued decades earlier would finally find, if not definitive confirmation, at least a significant foothold. And indeed, some of the most prominent scholars of the Lombard painter, including the aforementioned Marini and Vodret, Mahon, Cinotti, Calvesi and Gregori (until 1989) over the years, have supported Longhi’s attribution, though without ever being able to present as certain the identification of the painting cited by the export license with the one exhibited at Palazzo Barberini.

In the mid-1990s Vodret, with her article Il restauro del Narciso (The Restoration of Narcissus), attempted to delineate a plausible path, independent of the 1645 license, through which a Caravaggio painting could have reached Paolo D’Ancona two centuries later from Rome. In her reconstruction, the scholar called into question Cardinal Francesco Maria Del Monte, one of the Lombard painter’s earliest and most powerful patrons. Vodret had learned from the D’Ancona’s testimony that some of the art objects that Paolo had owned had been acquired by him through inheritance and came from a villa in Tuscany that had belonged to a paternal great-uncle, the Florentine banker Laudadio della Ripa, who, in the first half of the 19th century, had purchased a collection of paintings from the Giordani, a noble family from Pesaro. These data become more interesting, for the purposes of further study of the painting, when it turns out that at least two Giordani who lived in the seventeenth century, Giulio and Camillo, are attested to have had close relations, precisely, with Cardinal Del Monte.

In fact, however, we do not possess Laudadio della Ripa’s will, and the Giordani’s nineteenth-century inventories bear no trace of the painting, so nothing concretely supports the hypothesis, however suggestive, that the cardinal donated the canvas to the Marche family or that he favored its purchase in some way, and that it then passed to Laudadio and, from him, to his great-grandson.

More concrete arguments in support of the identification of Caravaggio as the author of the Narcissus, however, come from scientific analyses carried out in laboratories. Again Vodret reported that, in 1995, during restoration work on the canvas, which had been damaged by drastic cleaning and cut along all four sides probably due to nineteenth-century reintel, X-rays confirmed that, as is typical of Merisi’s works, there is no preliminary drawing beneath the painting.

That Caravaggio did not draw but painted directly in color is a widely held belief among scholars (with the notable exception of Alfred Moir, who considered the practice of drawing indispensable for the construction of at least the most character-rich and more complexly constructed works) and is based on what contemporary sources state, on the actual absence, to date, of a graphic work attributable to the artist with certainty, and on analyses of the paintings. Instead, the master made use of sketches defined only by color fields and engravings. The latter, traced with a brush handle or awl on the still-fresh preparation, are considered one of the characteristic features of Caravaggio’s achievements, because they are found with great frequency in his paintings. He probably used them as a reference for the positioning of the figures in the canvas. It cannot, therefore, fail to be of interest the engraving (although it is the only one) whose presence in the Narcissus was reaffirmed by the 1995 restoration; it had already been noted and appears placed along the outline of a sleeve in the part of the reflection in the water. In this area of the painting, radiographic investigations also identified pentimenti in the construction of the knee and that of the profile, which the artist modified by moving them upward after an initial pictorial intervention. In fact, the author created the image below by reversing the other by 180 degrees, and then intervened to correct some details and make the reflection more believable.Another significant repentance was identified in the hand on the right with which Narcissus tries to grasp his image in the water, which was initially supposed to show itself completely submerged.

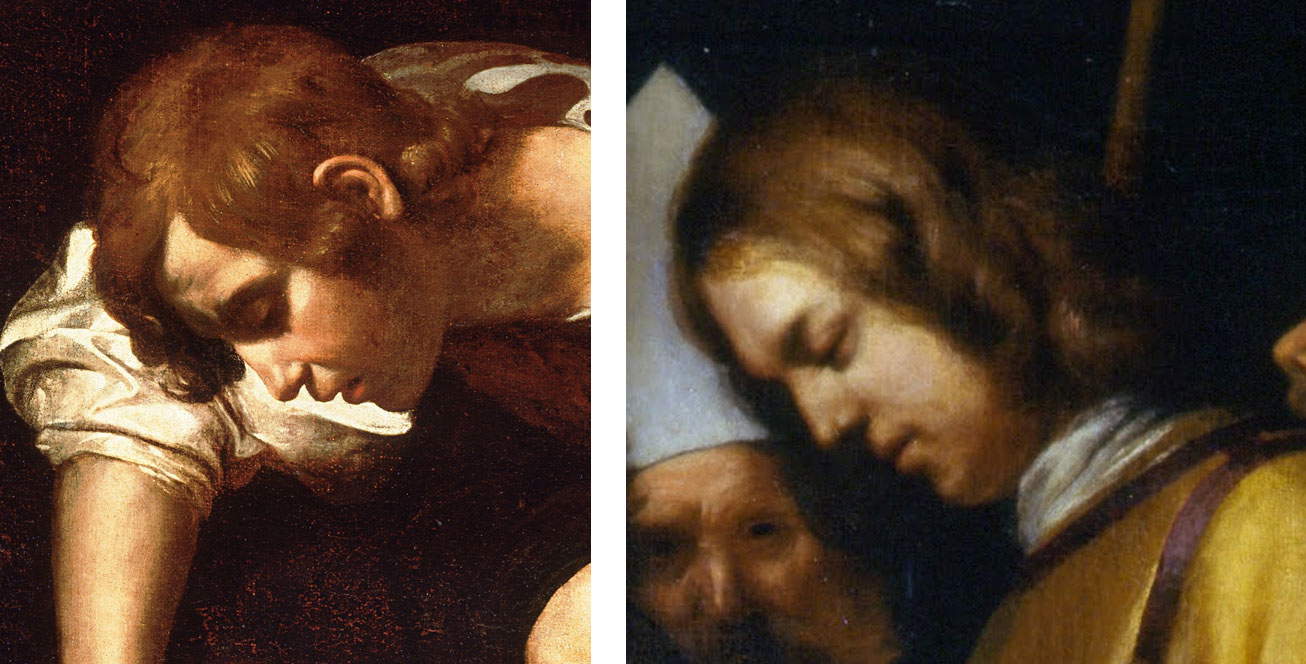

From a stylistic point of view, then, two features have been remarked upon by virtually all experts who have embraced the theory of Merisi’s authorship. Firstly, the definition of the embroidery on Narciso’s bodice, which is very similar to that of the design on Magdalene ’s dress in the painting exhibited at the Doria Pamphilj Gallery, made by the Lombard painter and dating, probably, to the last years of the 16th century. And also the Savoldoism of the Barberini Narcissus, that is, the reference to some elements proper to the pictorial language of the Brescian Giovanni Girolamo Savoldo (Brescia, c. 1480-after 1548), whose influence is evident in much of Caravaggio’s early pictorial production, but which, however, there is no reason to believe was unknown to the other protagonists of the early seventeenth-century Roman milieu.

|

| Caravaggio, Penitent Magdalene (1597; oil on canvas, 122.5 x 98.5 cm; Rome, Doria Pamphilj Gallery) |

|

| The embroideries of Magdalene and Narcissus |

Before introducing the arguments in support of a different attribution of the work, it should be mentioned that Vodret, in addition to his belief that the author is indeed Merisi, has repeatedly flanked that for which in the somatic features of the Narcissus are to be recognized those of the painter himself, who would therefore have performed a self-portrait. Obviously this theory does not convince scholars who recognize the painting to Spadarino.

As already mentioned, the absence of certain ancient sources on the Palazzo Barberini canvas has given rise to numerous speculations about the identity of its author, which, however, for obvious stylistic reasons, everyone places in the Caravaggesque sphere. During his activity, the Lombard master aroused the interest of many other authors who were inspired by the elements of novelty of which his artistic language was the bearer, such as, for example, the practice of painting from life, the frequent choice in a pauperistic sense for the settings and for the characterization of the characters, and the luministic contrasts.

It should not be thought that Merisi had pupils in the traditional sense, except Cecco and perhaps Bartolomeo Manfredi (we do not yet know whether the eponymous character mentioned in the records of the trial brought against Caravaggio in 1603, as “Bartolomeo servitore,” is to be identified with Manfredi or not). The adherence to Caravaggio’s style of painting, or that as much to style as to content, by some of his colleagues had nothing official about it. Some chose to take this path out of convenience, given the consensus the Lombard achieved among members of the Roman elite and beyond; others did so perhaps because they were more deeply affected by the implications of that powerful naturalism.

Among the early Caravaggists, the physician, collector and writer Giulio Mancini, in his seventeenth-century “Considerations on Painting,” also includes Giovanni Antonio Galli, the son of a sword-maker of Sienese origin who, unlike many others, never renounced never (at least according to what we have of him) a close adherence to Caravaggio, with a painting, however, softened by an elegiac note, by a sweet sensuality, and as Roberto Longhi wrote “without intention of drama, only of dreamy wonder.” Words, the latter, that are even more striking when reread when looking at the Narcissus, despite the fact that they were not thought of in relation to that painting (recall that the scholar believed it to be convincingly by Caravaggio).

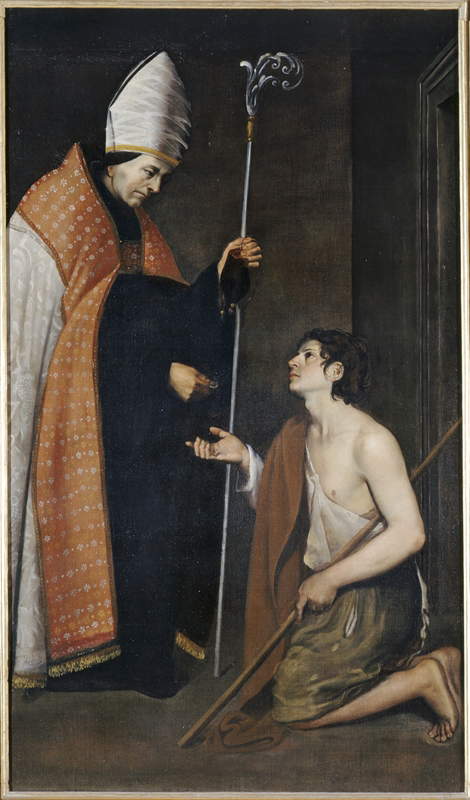

In 1943 with the article Last studies on Caravaggio and his circle, just mentioned, Longhi recovered the figure of Spadarino from the void in which it had sunk over the years, restoring to him a nucleus of five works starting with a series of comparisons with the only canvas documented as his, the one depicting Saints Valeria and Martial, now preserved in Rome in St. Peter’s at the Sala Capitolare. With the aforementioned intervention, Longhi revised some of his previous positions; before that time, in fact, he had attributed two of the five works, St. Anthony of Padua with the Child Jesus and The Alms of St. Thomas of Villanova to Caravaggio himself, as well as the splendid Guardian Angel of Rieti to Artemisia Gentileschi (previously assigned by Venturi to Merisi).

|

| Giovanni Antonio Galli known as lo Spadarino, Saint Valeria after her decapitation brings her own head to Saint Martial (1629-1632; oil on canvas, 320 x 186 cm; Vatican City, St. Peter’s Basilica, Chapter House) |

|

| Giovanni Antonio Galli called lo Spadarino (?), Elemosina di san Tommaso da Villanova (c. 1620; oil on canvas, 192 x 112 cm; Ancona, Pinacoteca Civica Francesco Podesti) |

|

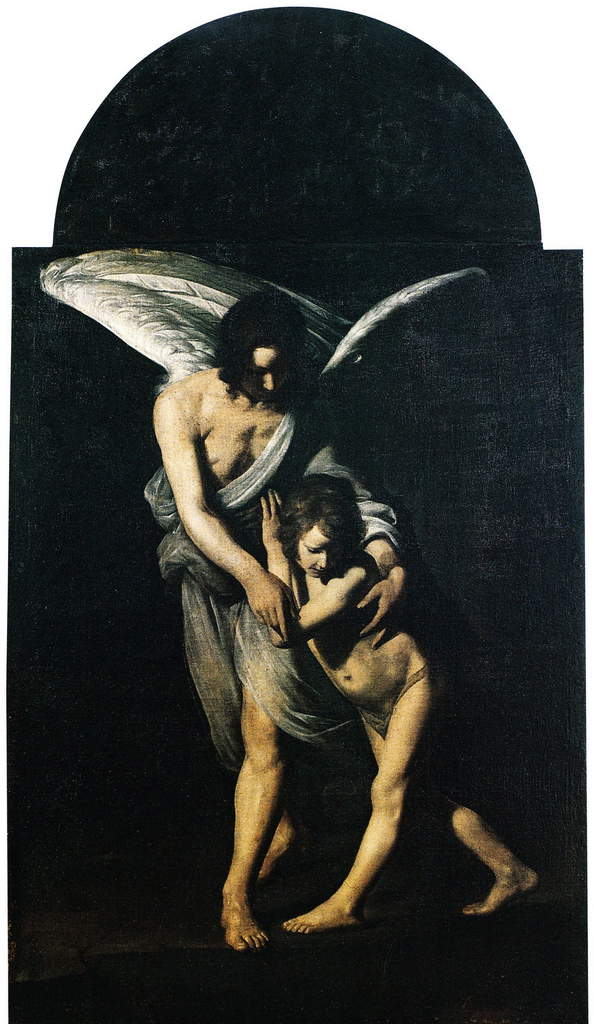

| Giovanni Antonio Galli known as lo Spadarino, Guardian Angel (1610-1620; oil on canvas, 200 x 150 cm; Rieti, Church of San Ruffo) |

More than thirty years later Cesare Brandi formulated, during his university lectures, the hypothesis that the Narcissus was the work of Spadarino, a hypothesis accepted, later, by authoritative names such as Clemente Marsicola, Giovanni Previtali and Ferdinando Bologna. Beginning with the text Una precisazione biografica e alcune integrazioni al catalogo dello Spadarino (A biographical clarification and some additions to Spadarino’s catalog), published in 1986, Gianni Papi, deepened Brandi’s address, contributing then, even later, to shed light on the figure of the seventeenth-century painter.

Following his intervention, in 1987, Elisabetta Giffi Ponzi with her article Per lo Spadarino adhered to the attributive hypothesis of her colleague, without, however, straying too far from the opinion that the conception of the work was beyond Galli’s possibilities, since she proposed to read it as a derivation from an original by Caravaggio. However, subsequent studies of the painting have revealed the aforementioned regrets, making it clearly an original creation.

Alongside Giovanni Antonio Galli, other artists have been suggested as possible authors of the Barberini Palace canvas. In the last century, the name of Orazio Gentileschi, for example, was mentioned by Dora Panofsky and Fritz Baumgart, while Bartolomeo Manfredi was indicated by Alfred Moir. However, the attribution to Spadarino is the one that has recently gained the most credence among art historians. Starting precisely from the 1645 document, Papi observed that, even assuming that it referred to the Barberini painting, one should take into account the fact that in the mid-17th century there was a tendency to attribute very casually to Caravaggio works that were not his, either out of interest or simply by mistake.

Providing Papi with an interesting argument to support Spadarino’s authorship of the Barberini canvas was a painting depicting The Baptism of Constantine, now preserved in Colle Val d’Elsa, which the scholar had first returned to Galli (an intuition later confirmed by the discovery of the inventory of the painter’s possessions at the time of his death, in which the work in question appeared). Indeed, the similarity of the mythological hero’s profile with that of the cleric on the right, who looks toward Constantine prostrate to receive the sacrament, is interesting. Papi observed that beyond the fact that the faces are depicted in the same position, the two noses appear superimposable, the chromatic quality of the epidermis is similar and so is the soft texture of the auburn hair; the pictorial treatment also appears similar. The main obstacle to the theory that Spadarino had resorted to the same model, portrayed on two separate occasions, lay in the considerable chronological distance between the paintings; the one in Colle Val d’Elsa, in fact, can be placed a little past the middle of the seventeenth century, while the most widely accepted dating of the Narcissus placed it at the beginning of the century. Papi then proposed postdating the execution of the latter painting to around 1645, supporting this further hypothesis precisely with the export license that year. In 2010, in fact, within the catalog of the Caravaggio and Caravaggesque exhibition in Florence, in the card dedicated to the painting depicting the emperor in the act of being baptized, the scholar speculated that by virtue of the great demand for originals by the Lombard painter, Spadarino may have made the Narcissus, and then passed it off in the same year to Valdibella, or whoever, as Merisi’s creation.

Even in the Convito degli dèi in the Uffizi Galleries, which shows a banquet in Olympus, executed by Spadarino much earlier, probably in the early 1920s, Papi found similarities with the Narcissus. First in the composition of the figure of the young cupbearer Ganymede: if one turns it over, placing it in the same pose as Narcissus, one will notice that the ratios of the head, shoulder and left arm are the same, as are their individual positions.

|

| Giovanni Antonio Galli known as lo Spadarino, Baptism of Constantine (oil on canvas, 303 x 200.5 cm; Colle Val d’Elsa, Museo Civico) |

|

| The faces of the Narcissus and the cleric in the Baptism of Constantine |

|

| Giovanni Antonio Galli known as the Spadarino, Banquet of the Gods (1620; oil on canvas, 124.5 x 193.5 cm; Florence, Uffizi Gallery) |

It is interesting that the art historian and well-known popularizer Tomaso Montanari, who has adhered to the attribution to Spadarino of the Narcissus, in an episode of the TV program Caravaggio’s True Nature, dealing with the Barberini painting, called the very comparison between the two figures of Narcissus and Ganymede, proposed by Papi, impressive and decisive.

And even the red mantle on the legs of Jupiter (a profoundly Caravaggesque character, with shaggy hair and a body described with vivid realism in its yielding to age) in Papi’s opinion, is reminiscent of the white sleeves, bathed in light, of the protagonist of the Roman work: the author observes that in both cases a cautious and almost hesitant manner of giving the brushstrokes is noticeable.

During some radiographic analyses carried out on the Barberini canvas in the early 1990s (thus before the 1995 restoration), the expert Thomas M. Schneider, studying the general layering of color in the painting, had identified a modus operandi that in his opinion differed from Merisi’s usual one. He had therefore concluded, “To achieve a construction such as this one, Caravaggio’s intervention would manifest itself with more vehemence and, despite his characteristic shifts and changes, with more clarity,” as he reported in the technical data sheet included in the catalog edited by Mina Gregori, Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio. How Masterpieces Are Born, which accompanied the exhibition of the same name held between 1991 and 1992, aimed at disseminating the knowledge gained through laboratory analyses promoted by the Longhi Foundation on Merisi’s canvases, and during which our painting was exhibited as Spadarino’s.

However, regarding the detail of the sleeves, Vodret, who had also noted the distance of this execution “characterized by the particular way of rendering the drapery with stiff and deep folds and with the thick and short brushstrokes to render the crumpled satin effect” from the usually long and thin strokes in Merisi’s draperies, remarked that a similar pictorial intervention is also visible in his early works more influenced by Lombard examples and, in particular, in the Vocation of St. Matthew, in the description of the clothing of the character from behind and the one sitting in front of the saint.

Finally, even Ferdinando Bologna in his L’incredulità di Caravaggio e l’esperienza delle cose naturali, in accepting Galli’s name as the author of the Barberini canvas, hinted at a possible proximity: that between the sparkles on the young man’s sleeve reflected in the water and the same detail in the cloth of St. Anthony, another work by the painter.

It is important, however, to remember that in the discourse of those who assign the famous Roman painting to Spadarino, those concerning character, in addition to stylistic observations, remain central: the painter’s great talent in devising real, human characters (which according to Papi only in Caravaggio is found at similar levels) and that soft, delicate and intimate intonation of the narrative that is characteristic of many of his works, one thinks of the aforementioned Guardian Angel of Rieti, the St. Francesca Romana of the BNL, the Charity of St. Omobono in the Roman church of the same name, to name a few.

In conclusion, the debate that has arisen around the painting is unlikely to lead to a solution to the dilemma shared by all, but it has certainly had the merit of stimulating further study of the work and that of an artist, Spadarino, who is still little known, yet decidedly fascinating. If then the intricate attributive affair of the Palazzo Barberini masterpiece, involving the painter, would also contribute to the curiosity towards the latter on the part of the general public, it would have already achieved an important result.

|

| Caravaggio, Vocation of St. Matthew (1599-1600; oil on canvas, 322 x 340 cm; Rome, San Luigi dei Francesi, Contarelli Chapel) |

|

| Giovanni Antonio Galli known as lo Spadarino, Saint Frances of Rome and the Angel (first quarter of the 16th century; oil on canvas, 42.5 x 69.7 cm; Rome, BNL Collection) |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.