Caravaggio at the Court of Cardinal Del Monte (I). The alchemical mural of the Casino dell'Aurora

Introduction by Giuseppe Adani

Michele Frazzi’s studies turn with strong intentionality to the search for the composite definition of the social and cultural world that enveloped Michelangelo Merisi in his shuddering Roman years, and in this space-as we will be able to grasp from the three contributions provided here-. what extraordinary importance the close stay with the exceptional personality of Cardinal Francesco Maria Bourbon del Monte, a true beacon and crossroads of science and literary love in the papal capital, had for him at the imaginative transition from the 16th to the 17th century. The merit of Frazzi’s great effort is to trace the causes of Caravaggio’s choices, often divergent and for this reason profound, careful, always linked to semantic truths and always nourished by multifaceted pictorial genius. Caravaggio thus appears there as a very strong co-star of a very high and decisive cultural season.

Cardinal Francesco Maria Bourbon del Monte

In Rome, after leaving Arpino’s workshop, things did not go very well for Caravaggio, who probably had difficulty in selling his works and was reduced to ill health: in this difficult predicament he was helped by Prospero Orsi and Costantino Spada (Mastro Valentino) who tried to sell his paintings, as Baglione testifies to us: “Yet he did not find to make a success of them, and give them away, and at a bad term he was reduced without money, and badly dressed so, that some gallant men of the profession, for charity, were relieving him, until Master Valentino in S. Luigi de’ Francesi dealer of paintings made him give away some; and with this occasion he was known by Cardinal Del Monte”.According to Celio instead it was again Prospero who introduced him into the house of the cardinal who was looking for a painter to make copies for him “Afterwards desiring the card.le de1 Monte a young man, who was going to copy some thing to him. Prosperino, there accommodated it Michelangelo. That to men him from the card.le looking all day, at the end he found him sleeping in the poggiolo next to Pasquino, who had no cloths around him. The card.le had him dressed and gave him rooms and part... ”. The painter, given his state of need, therefore adapted himself once again to making copies, an activity that moreover he had already carried out in the workshops of Lorenzo Carli or Antiveduto Grammatica, who was also in the service of the cardinal. Of this activity by Merisi we are left with the record of his copying a painting by Raphael that was part of the del Monte collection. Merisi, however, eventually succeeded in adequately exploiting to his own advantage the opportunity presented to him and soon emerged in the consideration of his patron and the cultural circle that gathered around him.The present Palazzo Madama, now the seat of the Senate, was at the time the residence of Cardinal Del Monte: this post, in addition to being accommodation with a very high-level and prominent member of the Roman cultural and political milieu, represented Caravaggio’s first safe and lasting harbor in Rome. He remained in her service “havendo parte, e provisione” for about three years, from July 1597 until several months in 1601. In this house, which was equipped with an atelier available to painters and a salon dedicated to music, Merisi began to enjoy a certain social prestige as a relative of the cardinal who was the ambassador of the Grand Duchy of Tuscany in Rome and represented its interests; the painter was also allowed to go around carrying a sword, which he evidently liked very much.

A character endowed with a learned erudition and a refined man, the cardinal could boast of excellent acquaintances not only in Rome and Florence but also in the Venetian sphere, in Padua and Venice, the city where he was born on July 5, 1549, and where Titian Vecellio and Pietro Aretino acted as his godparents at his baptism: this fact speaks volumes about the environment and ambitions of the family in which he was born. Francesco Maria Del Monte (fig. 1) began his career with Cardinal Alessandro Sforza di Santa Fiora, who was a relative of his (he was his second cousin), as well as being the brother of Faustina Sforza di Santa Fiora, marquise of Caravaggio. According to recent research, Cardinal Del Monte was also a member of the Accademia degli Insensati, an affiliation that may have come about through Cardinal Alessandro’s niece, Francesca Sforza di Santa Fiora, who had married the prince of the Accademia, Ascanio II della Corgna.

Leaving his post with Sforza after his death in 1581, he entered the service of Cardinal Ferdinando de’ Medici, and when the latter left the cardinal’s office in 1587 to become Grand Duke of Tuscany, he himself became a cardinal in 1588, also assuming the post of trusted man and “ambassador” of the Grand Duchy of Tuscany in Rome.

The Prince of the Republic of Letters: Gian Vincenzo Pinelli

Del Monte in his youth profitably completed his studies at the University of Padua, where his family had moved, and here he received his cultural education. It was in this city that Francesco Maria got to know and associate with a man who had a fundamental importance for the European cultural world: we are talking about the Prince of the “Republic of Letters,” Gian Vincenzo Pinelli (fig. 2), who was its regent, after Erasmus of Rotterdam, Thomas More and Pietro Bembo. It was Marc Fumaroli who described by this appellation the vast network of men of culture who exchanged opinions and ideas at both the scientific and humanistic levels, continuously advancing knowledge. This ideal space called the “Republic of Letters,” whose adherents were spread all over Europe, had a prince and a court, namely Gian Vincenzo Pinelli and his humanistic circle in Padua; he was its main animator, the center and engine of its progress. To his erudite assembly and consequently to the Republic of Letters, in addition to Francesco Maria and his brother Guidobaldo, who was one of the most important mathematicians of his time, belonged Marco Mantova Benavides (who was a teacher of Cardinal del Monte), Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc (the future prince of the Republic of Letters: it was he who had Maffeo Barberini publish his book of Poems, both of whom later belonged to the Roman Academy of the Humorists), Torquato Tasso (who was also a member of the Insensati), Marco Antonio Bonciari (a member of the Insensati and the Humorists), Galileo Galilei, Paolo and Aldo Manuzio (the famous Venetian publishers), the Florentine musicologist Giovanni Mei (a member of the Florentine Camerata dei Bardi), theFlemish humanist Justus Lipsius, Sperone Speroni, the physician-anatomist Girolamo Fabrici d’Acquapendente, Antonio Quarenghi (member of the Roman Academy of the Humorists), Giovanni Battista della Porta (founder in Naples of the Academy of the Secrets of Nature), Paolo Sarpi, the German botanist Melchior Wieland, the Scotsman Thomas Segeth, the Parisian jurist Claude Dupuy, Fulvio Orsini (Librarian of the Farnese family), Piero Vettori, Carlo Sigonio, Henry Savile (English mathematician), the Bolognese naturalist Ulisse Aldrovandi, founder of the first museum of natural sciences and author of the naturalistic encyclopedia, Marc-Antoine Muret (professor of moral philosophy at La Sapienza), Cardinal Bellarmino, Cardinal Borromeo, Cardinal Baronio, Francesco Patrizi (professor of Platonic philosophy at La Sapienza), cardinals Giovanni and Ippolito Aldobrandini of whom the latter became Pope Clement VIII (1592-1605), Girolamo Aleandro the Younger (founding member of the Roman Academy of Humorists) and finally Paolo Gualdo, thehumanist who wrote the biography of Pinelli; the latter also had the opportunity to frequent Caravaggio in Rome.

As Marco Callegari writes, "In many ways Pinelli’s home was the most accomplished realization of the ideal of the Respublica litteraria, in that in one place were concentrated, and made available to scholars, sources and instruments uniquely aimed at humanistic and scientific research with an international scope. " It was while attending Pinelli that Del Monte became acquainted with Giovanni Mei’s studies on Greek music and became passionate about this type of musical research that led Vincenzo Galilei to write the fundamental Dialogo della musica antica et della moderna (1581), a cornerstone of musicology at the time. Belonging to this milieu marked a fundamental stage in Del Monte’s intellectual aptitudes and future life, and when he moved to Rome he took up membership in Cinzio Aldobrandini’s circle where he found some members of the Paduan circle: the Pinelli himself, Tasso and Patrizi, and here he met Cesare Ripa.

The cultural circle of Cardinal Del Monte

The most accomplished fruit, the true legacy of Cardinal Del Monte’s frequentations at Pinelli’s circle and his membership in the Republic of Letters, was the creation of his own circle at Palazzo Madama. A patron of the arts and also of the sciences, he gathered a court of people of considerable cultural weight around him and was able to enjoy the friendship of lofty personalities of his time, including precisely Gian Vincenzo Pinelli, Cesare Ripa, Cassiano dal Pozzo, some musicians such as the founder of the Camerata: Giovanni de’ Bardi, Girolamo Mei, and Emilio de’ Cavalieri; humanists Fulvio Orsini, Francesco Patrizi, Gian Vittorio Rossi, and Girolamo Aleandro, as well as the most important men of letters of the time, Tasso, Marino, and Battista Guarini; and men of science such as physician Giulio Mancini (later biographer of Caravaggio), Federico Cesi (the founder of the Accademia dei Lincei), Fabio Colonna, Galileo Galilei, and also, of course, his brother Guidobaldo Del Monte. Guidobaldo was one of the most important perspective scholars of his time and his works are a cornerstone of the history of perspective science. To better frame the depth and breadth of the cardinal’s personality and insight, one can reflect on the fact that, in addition to protecting Caravaggio, he was also the protector of Galileo to whom he secured a position as a reader at the University of Pisa in 1588; Del Monte was thus the patron of the greatest artist and the greatest scientist of his time. The cardinal also held several important positions in the papal sphere: he was prefect of the fabbrica of St. Peter’s, and several of his additional positions involved music. To these responsibilities should also be added that of greater prestige: the role of official protector of the Accademia di San Luca, that is, the most important academy that brought together the painters of Rome. The Cardinal was, in short, one of the most prominent and also powerful personalities in the sphere of Roman artistic culture, within which by means of his assignments he had assumed a guiding role, a task he also performed with regard to the painters who were in his service, such as Caravaggio, whom precisely for this reason he called “my students.”

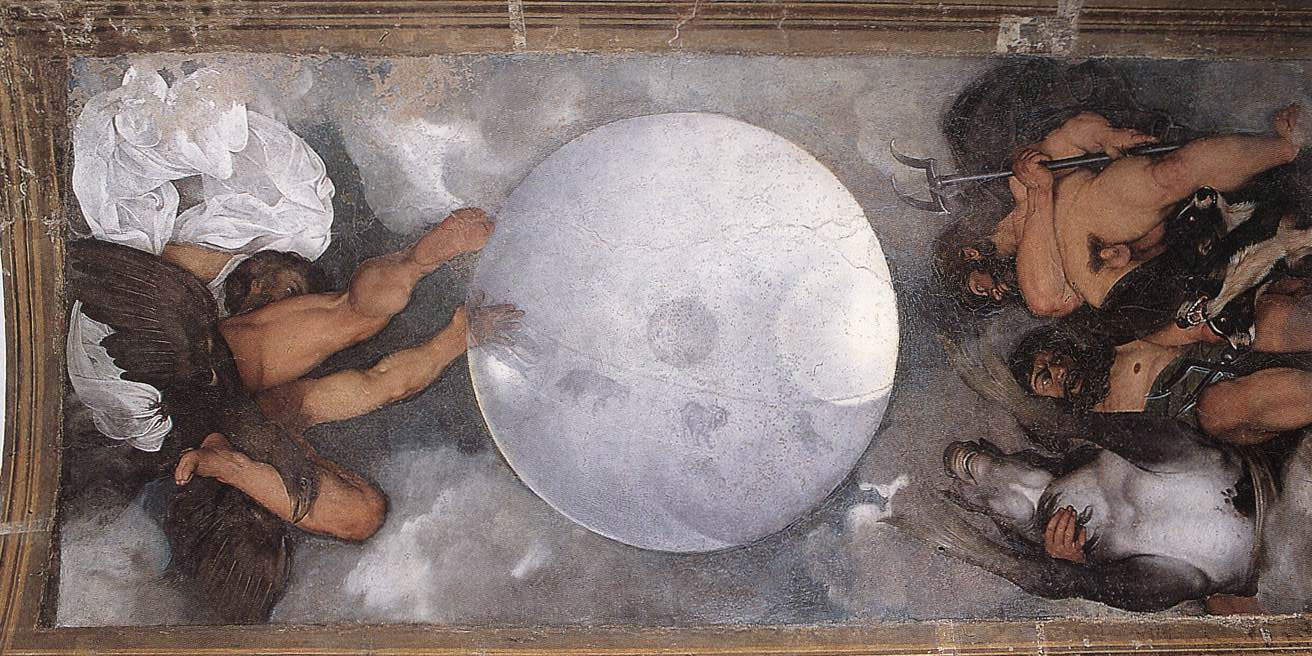

The fresco with the gods

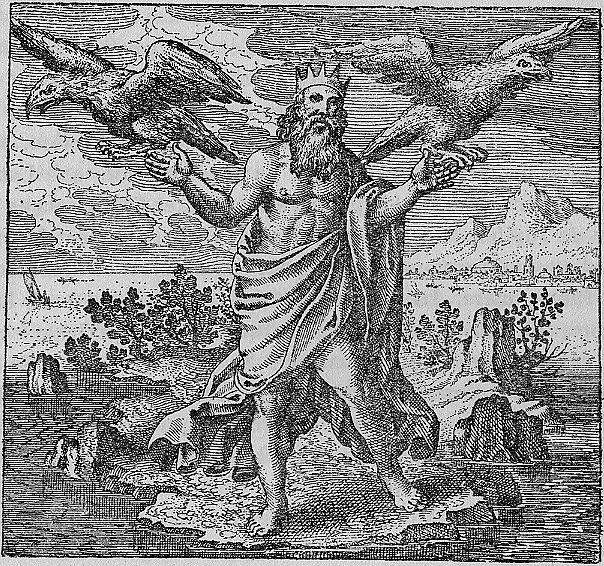

Concerning the paintings executed for the cardinal we can see that some achievements were related to themes of Caravaggesque invention; more interesting now appear the novelty of the works whose invention was born precisely by virtue of the contacts with Del Monte, so we will begin the analysis of these works with an important painting executed to satisfy the interests of his patron. During his stay in the cardinal’s house, at the request of his patron, who according to historical sources was a devotee of alchemy, Caravaggio executed his only known “fresco” (316 by 152 cm, fig. 3), which depicts the three sons of Saturn: Jupiter in his white cloak riding an eagle in his natural element (the sky), Neptune in his green cloak and trident sitting on his sea horse, and finally Pluto in his black cloak symbolizing the darkness of Hades (he holds the gallows and is accompanied by his three-headed dog, Cerberus). As we have seen before, Caravaggio, in making this work took inspiration from an engraving by Goltzius, from Titian (topics we will discuss in more detail below), and also may have taken as reference the perspective fresco works of brothers Antonio and Vincenzo Campi or the fresco of Mercury painted by Camillo Procaccini (fig. 4) in the nymphaeum of Pirro Visconti.

Monte’s fresco is mentioned from ancient times as the work of Caravaggio, in fact Bellori describes it as follows: “Tiensi ancora in Roma essere di sua mano Giove, Nettuno e Plutone nel Giardino Ludovisi a Porta Pinciana, nel casino che fu del cardinal del Monte, il quale essendo studioso di medicmenti chimici, vi adornò il camerino della sua distilleria, appropriando questi dei a gli elementi col globo del mondo nel mezzo di loro. It is said that Caravaggio, feeling blamed for not understanding either planes or perspective, so helped himself by placing the bodies in view from below upward that he wished to counteract the most difficult views. It is well true that these gods do not retain their own forms and are colored in oil in the vault, Michael never having touched a brush in fresco, as his followers together always resort to the convenience of oil color to portray the model. ”The historian, in his excerpt, accurately describes to us a first peculiarity of his: that of having been painted in oil and not with water pigments as is usually used in frescoes. He also gives us the further information that the setting in which the work was placed was a distillery. This second detail has also proven to be accurate; in fact, Frommel has traced the inventory of Del Monte’s possessions compiled in 1627, where not only all the instruments with which that room was equipped that made it a well-equipped chemical laboratory are listed, but also the rest of the paintings that adorned that space; it is therefore necessary to analyze the whole context in order to understand precisely what the meaning and character of Caravaggio’s fresco was, which must necessarily have conformed to the rest of the furnishings contained in the room. We do not know whether Del Monte dabbled in chemistry only with a scientific interest or whether he also studied and practiced alchemy proper, but the second hypothesis seems the most likely, since at the time the boundaries of these two disciplines were rather uncertain. Wanting now to make a point-by-point inspection of the numerous chemical equipment in his laboratory we find there a: “Fornicello of copper made in the shape of a tower with Walnut Feet, with small columns, and with eight vases to be distilled with a little figure at the top of a skull,” which because of this figure has all the appearance of being an atanor (fig. 5),which as the inventory describes isan oven that was used by alchemists to purify the raw starting matter. The skull with which it is adorned most likely alludes to caput mortuum, the symbol of nigredo, putrefaction, and that is, the first stage of alchemical distillation.

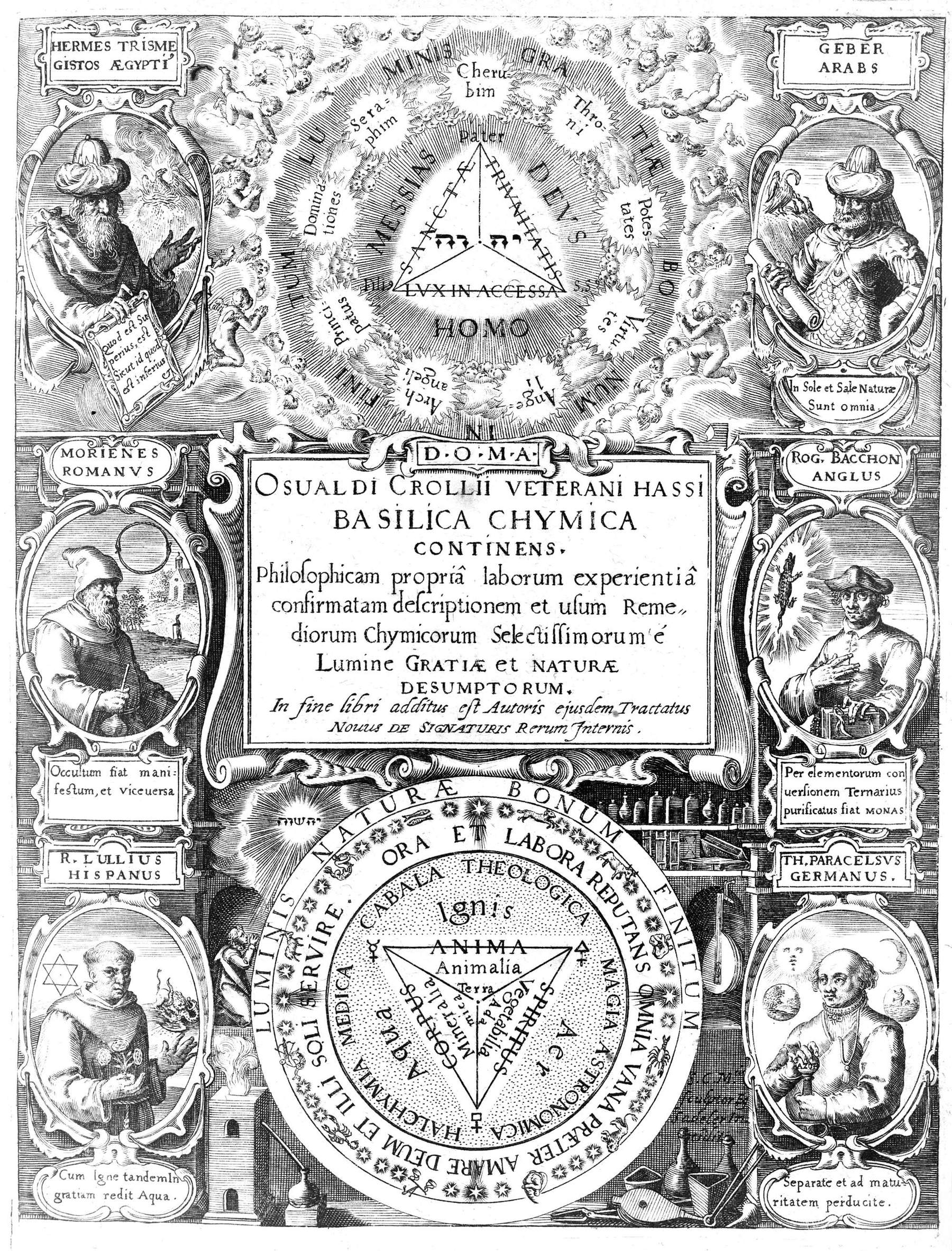

In addition to this object, we also find in the inventory “a philosophic gold with its foot and two padlocks” and “ two other philosophic ovi of copper without a foot”; at this point there is no doubt as to the purpose of these objects, since the philosophic egg is a term used specifically in alchemy (it is in fact an ovoid-shaped container that was part of theatanor and was intended to collect purified matter: the use of the philosophical egg was particularly studied by Roger Bacon, whose portrait is found among those that adorned the studiolo). It should also be borne in mind that the mysterious philosopher’s stone, the object of all alchemical research, was also called by another name and that is “the gold of the philosophers,” a very timely term that is also mentioned in the inventory to describe another container that is called “a philosopher’s gold,” intended to collect the fruit of the alchemist’s labors. In addition, as also noted by Spezzaferro, the Camerino Del Monte was adorned with several paintings that all portrayed figures related to the alchemical world: Isabella Cortese who was the author of a treatise published in 1561 concerning alchemy, medicine, and the preparation of ointments; Andrea Libavio who was a German physician who dealt with both alchemy and actual chemistry; and Arnaldo di Villanova, the alchemist physician. In addition to these portraits, on the walls hung an additional group of 6 paintings accompanied by explanatory inscriptions that leave little doubt as to their alchemical significance: we find Morienus Romanus, a legendary hermit and alchemist who lived near Jerusalem around the 7th century his image bears the motto(Occultum fiat manifestum et vice versa), a painting of Hermes Trismegistus, alsoalso a legendary figure who was believed to be one of the fathers of alchemy (with the motto Quod est sit perius, est sicut id quod est inferius), then a portrait of Paracelsus who was one of the most famous alchemists, with the inscription AZOF (i.e. AZOTH, the quicksilver of the alchemists) and the motto Separatem et ad maturitatem reducitem, one by Roger Bacon, the English philosopher who dealt also in alchemy (with the motto Per elementum conversionem ternarium purificatus fiat monas), one by Ramon Llull the forerunner of combinatorial calculus and alchemist (who bore the motto Cum ignis tandem in gratiam redit acqua), one by Geber who was one of the most famous medieval alchemists and also dealt with actual chemistry, with the motto In sole et sale nature sunt omnia. The phrases accompanying the portraits are all related to alchemical “science.” These six images of alchemists are all contained, with the same exact inscriptions as in the paintings in the dressing room, on the title page of a book: the Basilica Chymica (fig. 6) by Oswald Croll, a physician-alchemist follower of Paracelsus and adviser to Emperor Rudolf II. Thus there seems to be a connection between the dressing room and this book, although the nature of this relationship remains to be understood-in fact, the book was published in 1609.A clue can perhaps be found in the fact that Croll traveled to Italy and in particular went to Naples where he became well acquainted with Giovan Battista della Porta, whom he mentions in his book: he may therefore have passed through Rome and seen the dressing room. If so, in this image we can get an idea of the portraits that were in it.

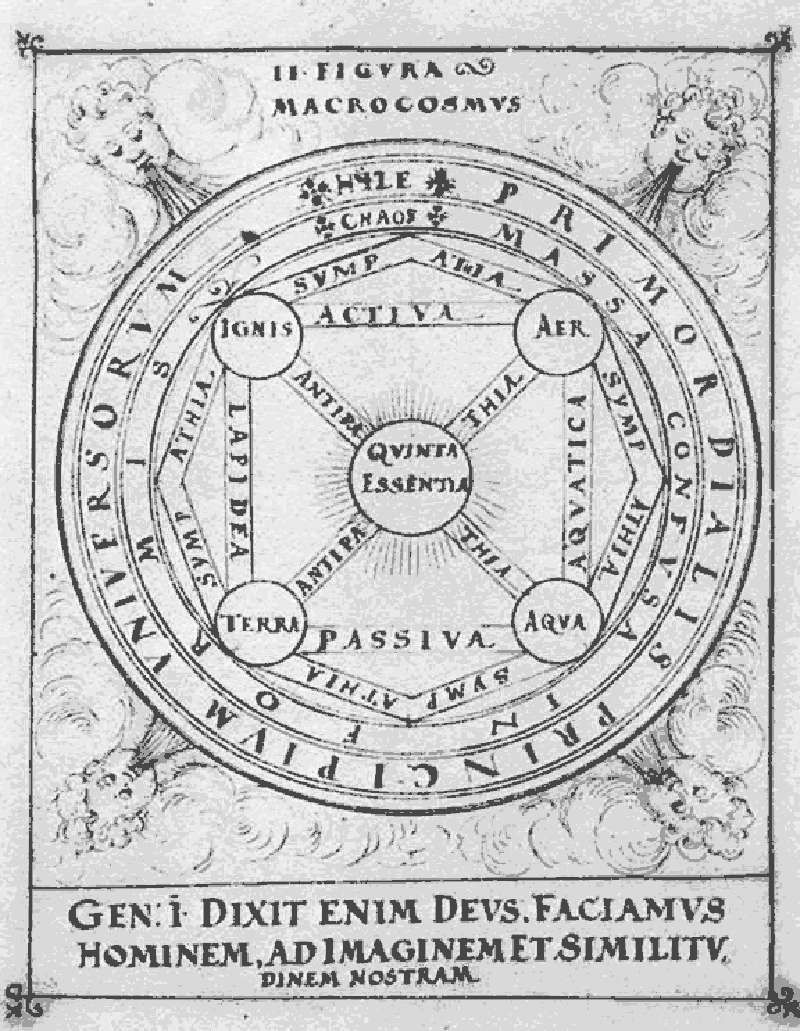

Consistent with these assumptions, Caravaggio’s fresco also shows many interesting symbols that direct its reading in an alchemical key: in fact, the three deities represented are traditionally linked to the different phases of alchemy and to the colors that are characteristic to each of them; their three images are found together in an illustration of an alchemical text, theEscalier des Sages.

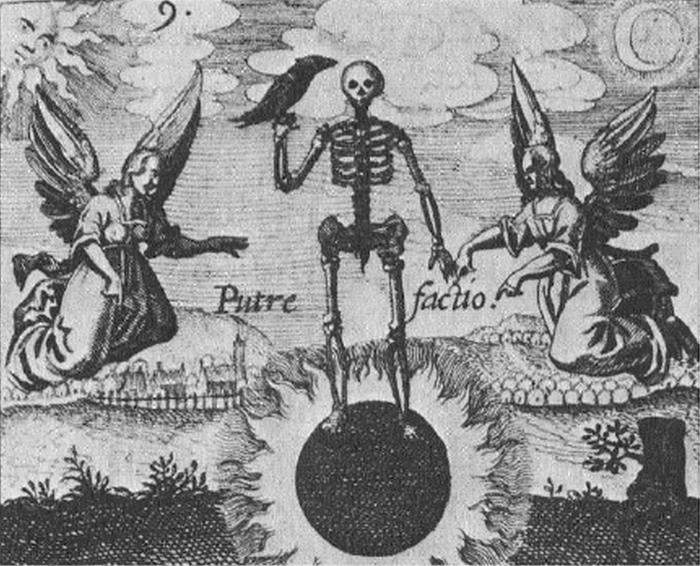

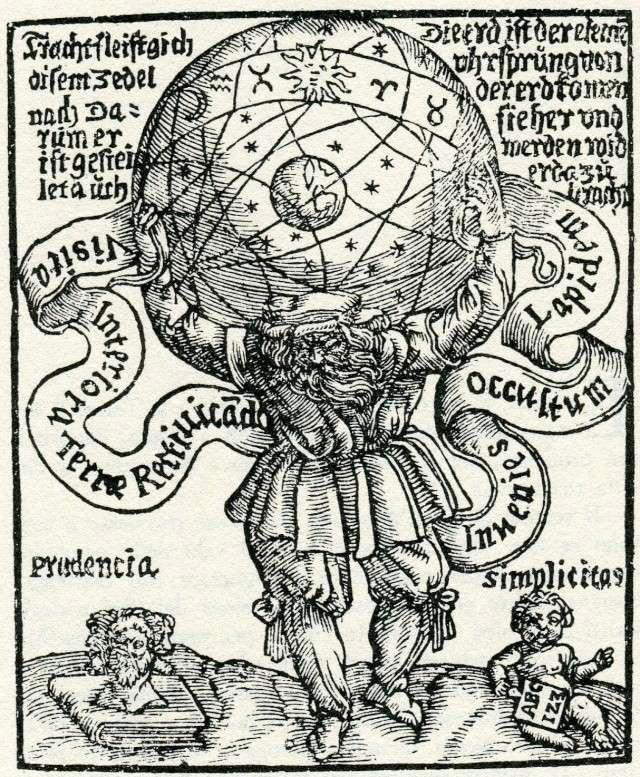

Pluto with his black-colored mantle is to be associated with the first phase of the work: the Nigredo (Work in Black), which represents not only the raw material from which one starts to arrive at the philosopher’s stone, but also the inner emotional state in which the alchemist finds himself at the beginning of his journey, a state that is one of depression, despair, abandonment, and loneliness. This is a psychological condition that is identified with Melancholia, as seen in Dürer’s print of the same name.It is necessary to keep in mind that alchemical stages should always be understood on two planes that run parallel to each other, the external and concrete one that concerns the world of matter and the chemical operations that transform it, and the mental one relating to the inner states that are created in the alchemist during the making of the work. The first step with which the alchemist begins his journey is identified symbolically by Pluto, lord of the underworld, in the depths of the earth (and the alchemist’s dark interiority): this is the first step in the alchemical procedure, which is identified as a whole by the alchemical motto: Visita Interiora Terrae Rectificando Invenies Occultum Lapidem, i.e. VITRIOL, the phrase translated into Italian means: visit the interiority of the earth and by rectifying you will find the hidden stone, i.e. the philosopher’s stone. In the path outlined here, three steps are identified to be carried out in sequence: 1) visit the interiority of the earth, 2) perform the operation of rectification (i.e., purification), 3) and you will find the philosopher’s stone (the first step is thus related to the Earth element). We find this alchemical motto represented in this image (fig. 7) taken from the book, published in 1613, which was written by Basil Valentine, a 15th-century alchemist, and titled Azoth, a fundamental term for alchemists (and in fact we find it in the Mount’s laboratory under the portrait of Paracelsus).

The next stage therefore consists of a purification process: on the material plane it consists of the elimination of the dross present in the starting matter, while on the inner plane the descent into the interiority of the earth, the descent into the underworld in the dark depths of one’s own being, must be followed by the elimination of the harmful elements in order to then begin the ascent upward, toward purity of spirit. For the alchemists, this activity had to be accomplished by means of an agent, a green-colored liquid called Vitriol: this is the protagonist and the fundamental element necessary to carry out the following alchemical phase, which translates on the material operational level into the refining of a compound by means of a chemical operation that the alchemists call “Rectification,” from the Latin rectificare, meaning to make correct: the term is still used in modern chemistry to refer to the distillation of a pure element from a compound, while at the level of the alchemist’s inner self in the same way a process of spiritual purification takes place. For alchemists, this substance called Vitriol has the property of being able to dissolve all kinds of matter and has been much studied in the field of Arabic alchemy, especially by Geber (the portrait of this important alchemist is among those that adorned the Del Monte dressing room).

The second step of the alchemical path is traditionally linked to Neptune, since it consists of a washing activity to purify the raw material: this stage is identified by the Water element of which Neptune is king, and the color associated with this stage is Green since the element used is Vitriol which is precisely green in color (we see it symbolically represented in the fresco by Neptune’s green cloak). In this phase the black starting matter is washed and purified in order to be freed of impurities: this passage in alchemical texts is called Viriditas (Work to Green), and its fundamental element is Vitriol, which is used to make the raw matter finally become pure and white (white will thus be the color that for the alchemists identifies the next phase, and in fact we punctually find this color in Jupiter’s cloak painted in the fresco). The characteristic action of the second phase was also called Solutio, i.e., dissolution, because it can go so far as to completely dissolve the solid state of matter, so as to make the compound completely liquid, transforming it into what is called, philosophical mercury i.e., the Azoth: the Vitriol is thus the tool needed to get to the point of producing the Azoth.

The three most important scholars of the Azoth or philosophical mercury were Geber, Paracelsus and Morienus, and all three their portraits in fact are found punctually among the paintings hanging on the walls of the distillery. The purification process we have just discussed, on the other hand, is described in the studiolo below the portrait of the alchemist Ramon Llull: Cum ignis tandem in gratiam redit acqua, meaning “through fire we return to water,” since the processes of distillation are carried out by means of the heat of fire and the result of distillation is a liquid substance, Azoth.

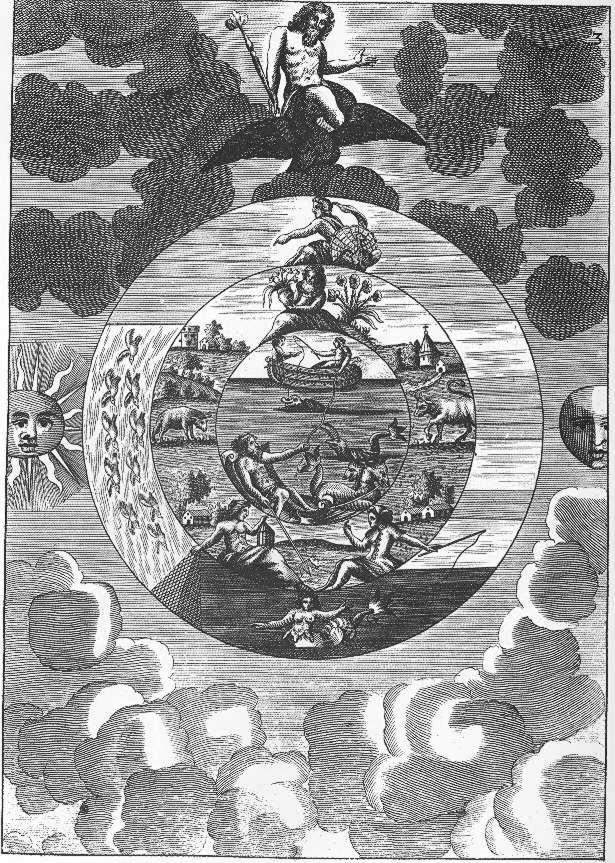

From a concrete point of view, these first two steps that we have just described are part of the phase that in alchemy is called Solve, a term by which we identify the first part of the alchemical procedure summarized in its completeness by the famous alchemical motto Solve et Co agula (“first dissolve and then coagulate”). The procedure, or subsequent purification procedures since this activity could be repeated several times, were also called by the appellation “Sublimation,” a term that even today in common parlance means to elevate to a greater degree of purity. This word is used in modern chemistry to refer to the transition of a substance from the solid state to the aeriform state, and the alchemists also called this operation by another name(Eagle),and described it as the process necessary to obtain a completely pure element that would later be the constituent of the philosopher’s stone. And it is indeed an eagle that we see, painted in the fresco, raising (sublimating) Jupiter, the king of the air, wrapped in his mantle of White color which is the color that identifies the third phase the one that is called Albedo (Work to White). The color associated with this phase is White and the element that identifies it is Air: in treatises on alchemy it is always linked to the figure of the king, as seen in an image taken fromAtalanta fugiens (fig. 8), because this passage preludes the Re-bis, the double king, the union of opposites, which will later be synthesized in the philosopher’s stone.

At this point, following a clockwise circular path in the painting, we have reached the culmination of the purification process, and Jupiter is placed in the fresco in the apical position. The figures of Pluto, Neptune, and Jupiter are used by alchemists because they are the lords of the three kingdoms-Earth, Water, Air-the three states through which the raw starting matter (solid, liquid, aeriform) must pass

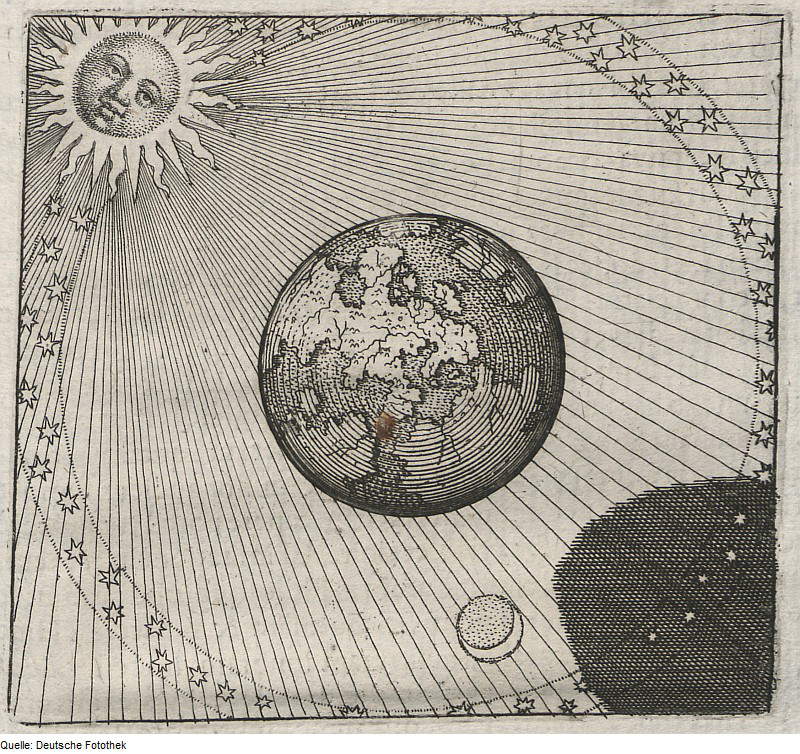

The alchemist has now finally reached a period, for he has started from a black, raw element and arrived at producing an element so pure and white that it is almost incorporeal, consisting of only one element: this is the process of purification leading to the isolation of a totally pure element, which in the paintings of the Del Monte dressing room is described in the text adorning the portrait of Paracelsus(Separatem et ad maturitatem reducitem), or the one under the portrait of Bacon. Now the phase called Solve has definitely ended and the Coagula phase needs to begin. We are helped in this regard by the indications provided by another of the alchemists portrayed in the Mount’s dressing room: Hermes Trismegistus. This author wrote one of the oldest, and perhaps the most important, of the alchemical texts (his translation from the original Arabic to Latin dates to 1250): the Emerald Table, which was written on a green-colored table. The treatise explains in great detail the alchemical process in its entirety and begins, “It is true without falsehood, certain and most true, that what is below is like what is above and what is above is like what is below to make the miracle of the one thing. And since all things are and come from one, by the mediation of one, so all things came into being from this one thing by adaptation. The Sun is its father, the Moon is its mother, the Wind carried it in its womb, the Earth is its nurturer. The father of everything, the purpose of the whole world is here. Its strength or power is whole if it is converted into Earth. You will separate the Earth from the Fire, the thin from the thick gently and with great ingenuity. It ascends from the Earth to Heaven and again descends to Earth and receives the power of higher and lower things.” This scripture highlights and instructs us about what we are looking for, and that is the last phase of the alchemical process: until now we have ascended from Earth to Heaven (from Pluto to Jupiter) obtaining a pure and almost incorporeal substance, but now we need to begin the process of descending downward, we need to descend back to Earth, to realize the Coagula phase and return to the solid state. The complete path therefore has its beginning in the interiority of the earth and one’s own being, which is followed by a path of purification, and then finally returns to the earth in order to find the philosopher’s stone: this is the same path indicated in the acronym Vitriol, and this pattern is perfectly reflected by the images of which the fresco is composed. In fact, just below Jupiter, we find the representation of the cosmos according to the Aristotelian conception: if we look closely, this is the exact same iconography contained in the Vitriol print (fig. 7) where the Earth is placed in the center and is surrounded by the sun and the moon (and in fact the alchemist must now return to the earth in order to find the philosopher’s stone).

One can see something similar to what was depicted by Caravaggio in the fresco in an image taken from another alchemical text, the Mutus liber of 1677 (fig. 9), where at the top of everything stands Jupiter seated on the eagle and below him the terracqueous globe. It should be kept in mind that according to the conception in force at the time, the Cosmos was divided into two worlds: the sublunar world and the celestial world. The sublunar world included everything located below the moon, including the Earth, and was dominated by the four elements, while the celestial world included all the other portion of the universe, that which is located above the moon: the stars. Therefore, starting from the top of the universe, which is the point where Jupiter is and which also corresponds to the alchemical stage we had reached, we must begin the process of descent to the earth, so we must first cross the sphere of the stars (the celestial world), which in the fresco are represented by the band of the four zodiac signs: these symbols were not chosen at random, in fact each represents one of the four elements that dominate the sublunar world that lies below these constellations (in astrology each zodiac sign is linked to one of the four elements). As the Emerald Table says, “what is below is like what is above, and what is above is like what is below-the lower is the mirror of the higher.” this concept is also timely under another of the portraits that adorned the dressing room, the one depicting Hermes Trismegistus himself where the inscriptionQuodest sit perius, est sicut id quod est inferius appears. As far as the fresco is concerned, therefore, the pattern Pisces-Water, Aries-Fire, Taurus-Earth, Gemini-Air occurs; Fire, Water, Earth, Air are the four elements that dominate the sublunar world.

If we carefully compare the central part of the fresco with the depiction contained in the figure seen above of the VITRIOL (fig. 7), we can find there the exact same depiction as seen in the fresco, with the celestial globe, the four zodiac signs, the sun, the moon, and in the center the Earth: this makes us realize that we are back where we started. The zodiac signs here, however, are not exactly the same; there is only one significant change: instead of the fish sign present in the fresco we find that of Aquarius (it is, however, still a water sign). This variation, which is absolutely consistent with the logic we have just proposed, further confirms the correctness of reading the zodiac signs as symbols of the four elements. Their sequence is also not random: their precise placement in sequence alludes to the union of the opposing pairs of the elements, namely Water-Fire and Earth-Air. From the union of all four opposite elements will come the quintessence, that is, the substance that constitutes the philosopher’s stone (fig. 11). Continuing in the fresco our path of descent, we pass the zodiacal band and come to the orbit of the sun and moon that is opposite it: these two planets apparently both luminous are represented by two white globes, one smaller and one larger, and we find the same image in emblem 45 of the famous Alchemical Book, the Atalanta Fugiens (fig. 9). This image alludes to the marriage of opposites, the confrontation between light and shadow, between the masculine and the feminine; it is the phase that heralds their union, their marriage. As the Emerald Tablet says about the philosopher’s stone, “The Sun is its father, the Moon is its mother.” Descending still further we thus finally arrive at the center of the fresco, that is, at the Earth that represents the end of the alchemist’s journey. We have passed from an almost incorporeal state(Solve) to return to the solid state of matter from which we started(Coagula): now, however, the matter in our hands no longer consists of vile but purified substances, it is made only of quintessence (fig. 11): it is therefore finally the philosopher’s stone, the child of the masculine and the feminine, of the sun, the moon and the Azoth, which being a participant in both sanctions their union. We have finally reached the end of the Coagula phase and the philosopher’s stone, which is composed of the union of all four elements, that is, the quintessence, the fifth element.

The fresco therefore effectively illustrates in a complete way the process of creating the philosopher’s stone as described in the alchemical texts, and it makes precise use of the symbolism and imagery that are characteristic of alchemy. The sequence of stages depicted therein follows in a canonical manner what is expected: first the work to black, then the work to green, then the work to white. These three terms or colors symbolically testify to the passage of the raw starting matter through the liquid state to the aeriform state, and finally the alchemist must bring this pure substance back to the solid state to complete the circular path thus finally realizing the philosopher’s stone. In making this explanation, we have referred to concepts taken from the texts of the alchemists portrayed in the dressing room and the phrases that have been added beneath them: reading the meaning of the fresco cannot disregard the context in which it was placed (nor go beyond this) since it is part of and completes the furnishings of the studiolo, which should be read as a whole having its own coherence and homogeneity.

This work by Caravaggio, because of its complexity, represents one of the pinnacles of his ability to use the language of symbols, a skill that, moreover, we have already been able to appreciate while reading the meanings contained in his other youthful paintings: in making this effort he must undoubtedly have been helped by Cardinal Del Monte, who must have erudite him on the specific symbologies of alchemy and designed together with him this beautiful alchemical illustration.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.