What a blow to old Luca Carlevarijs this story was. He had been in Venice for some time devoted to picturesque landscape painting and was therefore also the leading specialist in topographical veduta, a genre he cultivated with the merit of technical-scientific study widely acknowledged to him. He seems to be, in the later part of the seventeenth century, the most gifted from the point of view of preparation, so much so that it is suggested that he was motivated on the problems of the mechanics of composition required by the topographical reconnaissance of places. Indeed, the portrait of the mature artist made of him by Bartolomeo Nazzari (Oxford, Ashmolean Museum) shows the instrumentation with which he habitually surrounded himself, globe, compasses, measurers, scientific texts and, only more defiladed, the palette.

As much as the master appears mechanical in construction, so much of the larity of vision emerges that would instead have been the quintessential Canaletto gaze applied to lagoon horizons.

Stefano Conti, the Lucchese nobleman who was heir to the family fortunes in the cloth market, was a widower and no longer traveled; it had now been several years since he had visited Venice, and therefore he longed for more views of Luca Carlevarijs, whom he knew and whom he wanted to rely on again to recall the happy hours spent in that spectacular city.

She turned to Alessandro Marchesini, a Veronese painter who had already guided her in her purchases, but was unexpectedly contradicted in a letter sent to her from Venice on July 14, 1725: “V.S.Ill.ma wishes for li due accennati quadri da accompagnare gli altri che tiene dipinti dal Sig. Luca Carlevari. But now truly lives the subject, if it were not surpassed in greater esteem by Sig. Ant. Canal, who makes in this country universally stun everyone who sees his works, which consists on the order of Carlevari but is seen there lucer within the sun.” Within a year or so, Canaletto devoted himself to four new views for Stefano Conti, which ended up in the Elwood B. Hosmer collection in Montreal: the Rialto Bridge and the Grand Canal from the Bridge, two views that develop the direction of the gaze right from the Lucchese client’s favorite apartment, and thus also linfinite nostalgia (and perhaps regret) for the place and happy days, and then the Grand Canal with Santa Maria della Carità and Campo Santi Giovanni e Paolo.

Perhaps the most beautiful passage, among the hundreds and hundreds of eighteenth-century letters, for a Venetian artist on his way to widespread fame is that stordire referred to by Alessandro Marchesini (étonner if we wanted to think of it in the most international language of the moment) and that is, something that leaves us shaken, motionless and dumb with wonder, momentarily less conscious, so much so that we need a fan to revive us, just to cultivate the habits of the era. This happened to the curious onlookers who saw Canaletto’s work displayed at the annual feast of St. Roch on August 16, 1725.

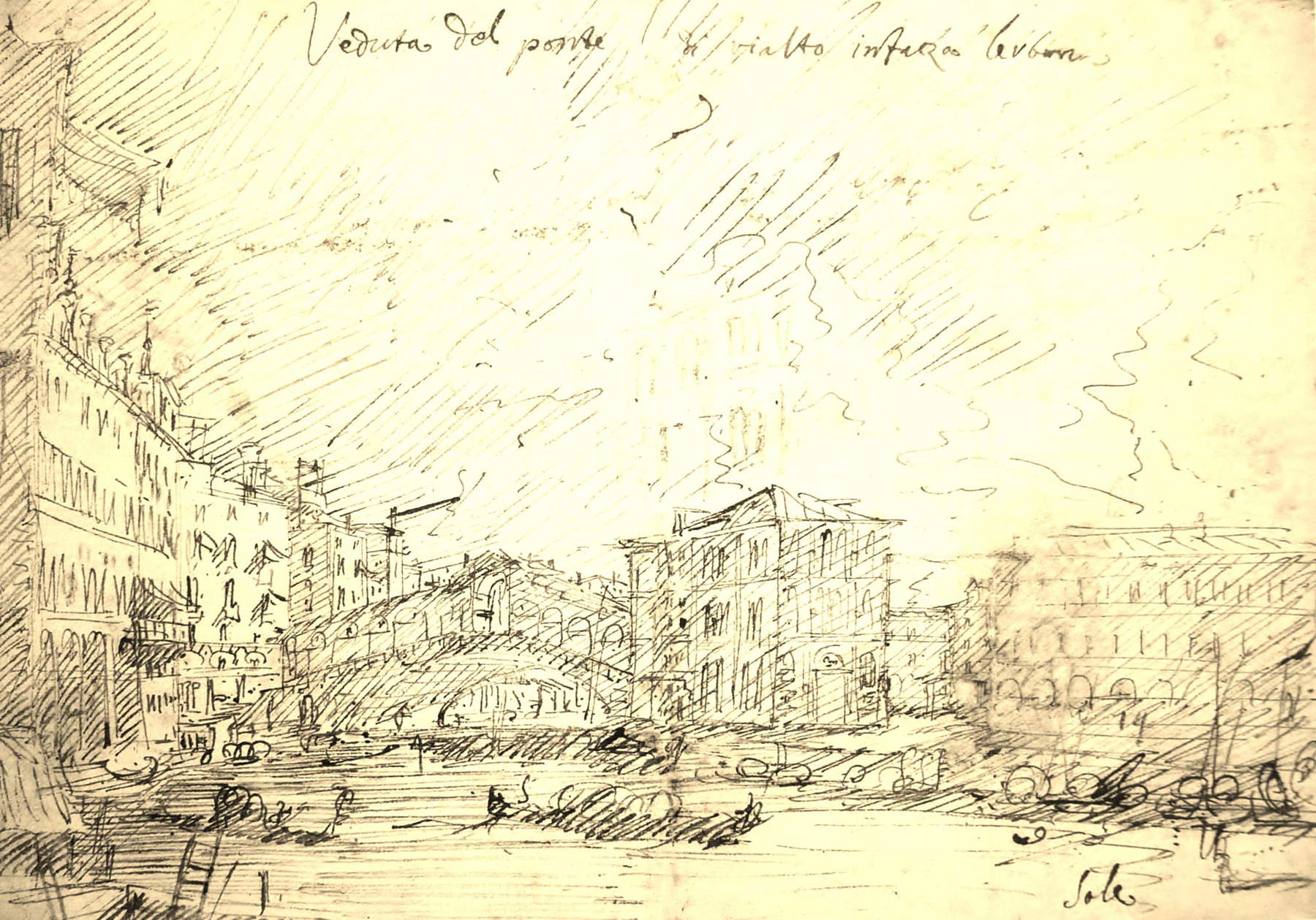

Such exquisitely formal convictions dress up Canaletto’s particular relationship with Luca Carlevarijs vedutismo. Therefore, Alessandro Marchesini’s references to the experience of light, which in some ways, though mute and motionless, appears visibly superior to our experience of it, appear more conspicuous, because they are internal to the device of the birth of modern Venetian veduta. A rapture of the senses and trigger of the persuasive deception of the eyes, as if the viewer were sucked into the wide-open skies of Venice. Canaletto seemed to enjoy a new vitality by going after that seduction directly on the places where it manifested itself, which, through the eyes, became the artist’s mental laboratory, the gateway offered by the elaboration of the sketches. Like the vividness of the drawing at theAshmolean Museum in Oxford, Veduta del ponte di Rialto infaza lerberia, made in preparation for the first painting commissioned by the Lucchese nobleman to Canaletto: the Venetian fragment was born allimpronta, without technical mediation, on the place and the moment, as the sun point at the bottom, on the right of the sheet, which corresponds punctually to the magnificent stroke of light on the water in the final version, is proof.

It is an eye that participates from the inside in the life of the city, that can now capture its shining of things, animate and inanimate, the certainty of time that is entirely identified with the work, if we consider, for example, the details of the scaffolding that describe what was happening in the city’s construction, with its transformations that allow us to date the paintings even if we do not possess written statements. Canaletto manufactured in turn, with charm and originality (and without copying), the city of desires; one did not yet buy glass, bags, shoes and other souvenirs, as is the case today, but the vision of that world, matured with the relative slowness of the style of travel, followed home in new visits, when the winter skies turned gray and (just a glance) the summer of Venice returned.

The discovery of reality revealing itself to the eyes in its fullest intentions is a free conquest of the eighteenth century, but one should not overlook how widespread were lattenzione and the study of the compositional mechanics proper to scenic installations. Indeed, for the visible to be a grand theater with its variations of light and things, it was advisable for a specialist to delve into the secrets of that technique. The common matrix to the rules of scenic composition, with lability to organize in verisimilitude the very different parts of the panorama, qualifies one of the peculiarities of the 18th century. The theme of capriccio in particular, which in itself represents a very special declination of the vedutistico genre, is the quintessence of the concept of variety and surprise, capable of clasping together reason and pleasure. Canaletto himself did not hesitate to devote himself successfully to this genre, although he had already found a precise vedutistic identity after his first experiences with lincarico as a set designer.

Side by side in a room of Villa Giovanelli in Noventa Padovana stood two giant canvases with class ruins that, architectures and figures; they had probably been purchased through the mediation of Domenico Coronato, one of the best-known picture shopkeepers in the Venetian square, owner of those peculiar stores comparable to some of today’s discount stores. But Canaletto, signing and dating 1723 one of the specimens (as rarely happened to him) wanted to warn that his skills were great and showed themselves in the three-dimensional space of whimsy. There the directorial idea is appreciated, landscapes are set up showing space and stage machinery together: to discover its secret better, one should imagine a kind of examination of the theater behind the scenes. And so one would become familiar with the compositional variants, with ever new scenery flattering the amateurs of the era to welcome into the drawing rooms of their homes that freak of nature, capable of bending to the picturesque arrangement foreshortenings and testimonies of the ancient grandeur of the cities visited.

We could also speak of whimsy for the eighteenth-century family of Palladian knowledge, with its past and the gravamen of myths and rituals (the trips between Venice and Vicenza, to say, to visit his works) that interested the good education of the European, especially English,upper class. Thus it was that the collaboration of Antonio Visentini and Francesco Zuccarelli took as its model the churches of San Giorgio Maggiore and the Redeemer, or the Palazzo Chiericati, set in a contour of countryside as unrealistic as it was inviting.

The gesture of love toward Andrea Palladio is fulfilled in the path that had found fertile material in the painted re-enactment accomplished by Canaletto at the behest of Joseph Smith, the British consul in Venice, famous for protecting artists, for invitations to the magnificent house on the Grand Canal at Santi Apostoli, where in the good old days there was also a market for paintings and other things. He had commissioned him thirteen sopraporte with monuments of Venetian architecture, including the best things of Palladio, San Giorgio Maggiore, San Francesco della Vigna and that Rialto Bridge on the project never realized by the great architect, which became a dress rehearsal for the most Palladian caprice in history, of which the learned Francesco Algarotti wrote in his letter of September 28, 1759, with Rialto again, Palazzo Chiericati and the Basilica of Vicenza: “a new kind, I would almost say, of painting, which consists in taking a site from life, and then adorning it with beautiful edifices either taken from here and there, or else ideal. In this way one comes to bring together nature and art, and can make a rare grafting of what has moon more studied on what the other presents more simple.”

Canaletto’s conversation with Palladio’s architecture continued in London, where he moved from 1746 for a decade damage. New paintings were in demand to spread the Vicenza legacy, such as the Church of the Redeemer, which resurfaced in England in the mid-nineteenth century to be repurchased with intact passion.

This view allows us to clarify how the balance between spatial verisimilitude and atmospheric sensitivity, while admitting all the technicalities of the camera ottica, a true ante litteram photographic instrumentation for setting the foreshortening, lies in the breath of the final representation, in which the complexity and all the energy of invention is concentrated, thus far beyond a simple compositional mechanics.

Venice in the eighteenth century had become one of the most popular cities in Europe, a place of appearances and pleasure for the traveling populace, mirrored in the work of the vedutisti and in that of Canaletto in particular, who could seem an exquisite flower all sentimental with his plein air to which he had been able to give ever new variations on some favorite t emes. That repertoire of his seemed to be revived again in London. In the great capital a sensibility for the veduta seems to be revitalized with the arrival in George III’s collections of Joseph Smith’s Canaletto (1762), when the artist had long since returned to Venice.

So many gifts would have warmed the hearts of the many lovers of Venice during the nineteenth century as well, and so it was that the paintings developed for Stefano Conti’s collection, among the many already there, entered the home of Robert Townley Parker in London in 1832, the city where Canaletto had long worked.

Already: the nineteenth century and the fortunes of Venetian vedutismo. Canaletto, who also did not have good relations with the home Academy, where he entered with difficulty only at the end of his career, continued to be copied in school desks through his famous engravings. He had no official glory, but for example we find leccentric Niccolò Tommaseo with a Christian Romanticist theoretical interpretation of the figure of the vedutista (1838), which he delivers to an ideal commentary based on some works seen in Montpellier, actually by Francesco Guardi. An artist, this one, rediscovered and discovered in the early twentieth century by Simonson and Damerini in a pre-Impressionist key because of the rapidity and lesuberance of his painting of views, those forms evoked among skies and waters that nevertheless appeared to be the result of an unregulated imagination to the devotees of late eighteenth-century classicism. Yet he did not fail to interest a small circle of amateurs, as Francis Haskell has told us by also investigating the releases of certain of his works during the nineteenth century, which were highly appreciated in England. One wonders how much they were not rather attracted to the traditional fortune of the vedutistico theme by resigning themselves to the absence in the collector’s market of examples by the renowned Canaletto, almost nothing by his nephew Bellotto, little by Marieschi, perhaps a few whims of Visentini, Joli and Battaglioli. “There remain Guardi’s things,” Pietro Edwards told the sculptor Antonio Canova, who from Rome in 1804 was interested in the subject, “as incorrect as ever, but very witty, and of these there is now much searching, perhaps because no better can be found. Ella knows, however, that this Painter worked for the daily loaf; he bought discarded cloths with dastardly imprimiture.” An image that in a kind of visual transference has left obvious traces in the artist’s graceless history, if still the Milanese Giuseppe Bertini portrayed him, in a painting presented at Brera in 1894, a little sullenly selling his little paintings to the idle customers of the cafes of Piazza San Marco.

Today, however, we remember him (and in some ways it makes an impression) with one of his most successful views, the Rialto Bridge with the Palace of the Camerlenghi, purchased in 1768 by the politician Chaloner Arcedeckne (still an Englishman traveling to Venice), which was offered at twenty-five million pounds at Christies in London in 2017.

As in some ways happened to Giambattista Tiepolo’s painting, Francesco Guardi’s judgment of modernity no longer contrasts with the qualities of immagination, things that now take on positive valence thanks to the passage of the umpressionists. Such as light, in its obvious traces that represented the vedutismo of Canaletto and Guardi himself; indeed better the latter than the former, with the freshness of the vivid gaze of memory, sprinkled with the colors of theimprovisation that reveals an instantaneous experience, rather than the other and his essays of an objective Venice, spaced from memory even in the technical preparation of perspective framing.

Viva Guardi, would have said from Paris Paul Leroi in the nineteenth century and, we add, his innocence that accompanies us forever within the illusion of Venice. And to think that it all began in the workshop of his brother Giannantonio Guardi. Between the 1930s and 1940s they were forced into the work of copyists from works of more highly-rated masters; products to be destined mainly for the collections of the Giovanellis and Johann Matthias von Schulenburg, who had included them among the poor on the payroll.

Reflection on theffective beginnings of Francesco Guardi’s vedutismo is not marginal, as critics still divide. Did the practice begin upon the death of his older brother, Giannantonio (1760)? And if so, how to justify a stylistic direction of Francesco’s vedutismo that was entirely opposed to the sunlight, which at the time had laid the pictorial genre on the attentions and understanding of the Canalettian eye? How could one think that the root of contemporary Vedutism, its grandeur and the novelty of the light radiating to infinity, qualities that amazed collectors throughout Europe, would find an answer in Venice so out of sync in the 1960s, that is, in Francesco Guardi’s first hypothetical attempts; cuts with deep atmospheres, almost as if the master wanted to propose a journey to the beginnings of Canaletto’s own manner? But we will have to go deeper into the deeper suggestions of Guardi’s training, before the most famous images of Venice, quilted with darting light and passed by air. A testimony dating back to the early 19th century tells us of a collaboration of Francesco Guardi with Canaletto in the execution of some views. This is a supposition, but it cannot be ruled out that an adolescent novice in painting, as he is known to have belonged to a poor family, could have helped an already renowned vedutista such as Canaletto was; discovering his ideas and the transition from a vedutismo contrasted in atmospheres, I would say picturesque as his views of the early 1920s seemed to have been. However, if that were true, who knows how he must have goggled at the two capriccios for the Giovanelli at the villa in Noventa near Padua.

A distant debt to Canaletto, quite normal for someone who lived practicing copyist work still during the fifth decade. And then the function of the stain with which he lights up the Venetian panorama of immobile architecture with life, for example in the figures, which we see traced in an UnExperience of style that the master built up in a sphere of consumption of the vedutistico genre of which one could also be a victim in the local market. Here is formed the characteristic of a master who would be among the leading interpreters of the second half of the century and who seems to commend himself to the fate of demand in the Venetian square.

And so it is that the eighteenth-century poetics on which the free combination of architecture and figures depends in the clear consciousness of the triumph of invention, seems to bend to that vision of wonder. One recognizes in it the confidence of the eye led to expand the space, and the quality of the compositional and atmospheric texture, all veering, it would seem, into the transparency of a sophisticated monochrome. Who knows, wanting to run with the imagination, we could also imagine that Francesco Guardi wanted to think of his city with his eyes closed, untouched, living humble but honest and serene days, which we see for the last time in his paintings. As if he never wanted to detach himself from that pleasure.

This contribution was originally published in No. 3 of our print magazine Finestre Sull’Arte Magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.