Boldini, Corcos, Toulouse-Lautrec: the women of the Belle √?poque in an Emilian collection

Boldini was the painter of his age: he painted women with shattered nerves, fatigued by this tormented century. His love-struck prostitutes, twisted in silk girdles with phosphorescent ripples, their corsets infioreted, their legs maddened, epileptic, their arms stretched out, ending in hands fringed like grapes, these dazzling visions zigzagging like emanations of heat, all these shivers, these tremors, these contractions, are in tune with this age of neurosis. Writing these words was Sem, stage name of Georges Goursat (Périguex, 1863 - Paris, 1934), illustrator and caricaturist and friend of Giovanni Boldini (Ferrara, 1842 Paris, 1931), the Italian painter who perhaps more than any other managed to embody the myth and at the same time the contradictions of the Belle Époque. In the collective imagination, this period between the last two decades of the nineteenth century and the beginning of World War I is substantiated by the female forms: sensual, refined, but also with shattered nerves, crazed, zigzagging. Beauty and seduction, desire and the first yearnings for enfranchisement from the male, often somewhere between the real and the coveted: the women of the Belle Époque take on the guise of Boldini’s sinuous femmes fatales, Toulouse-Lautrec’s procacious dancers, Vittorio Corcos’s elegant ladies.

The undoubted charm of the women of the Belle Époque had to strike no small chord with the great collector Giulio Bargellini, who granted considerable space in his collection to paintings of the time whose subject matter was, precisely, women. A passion all the more precious if we think that for some time now it has been housed in the museum, the MAGI 900, which he himself founded in 2000 in Pieve di Cento, in the province of Bologna: a museum set up in the spaces of an old grain silo that, since the date of its opening, has undergone continuous renovations and expansions. The section devoted to the Belle Époque is but the latest chapter in this story that began seventeen years ago. Paintings, prints, posters, photographs, and magazines have been brought together in an itinerary inaugurated on November 5, 2016 with an exhibition, entitled Homage to the Femininity of the Belle Époque, from Toulouse-Lautrec to Ehrenberger and curated by Fausto Gozzi and Valeria Tassinari, whose goal is to present this particular section of MAGI 900 to the public, providing a reading that placesItaly at the center of reflection but also opens up to an international perspective.

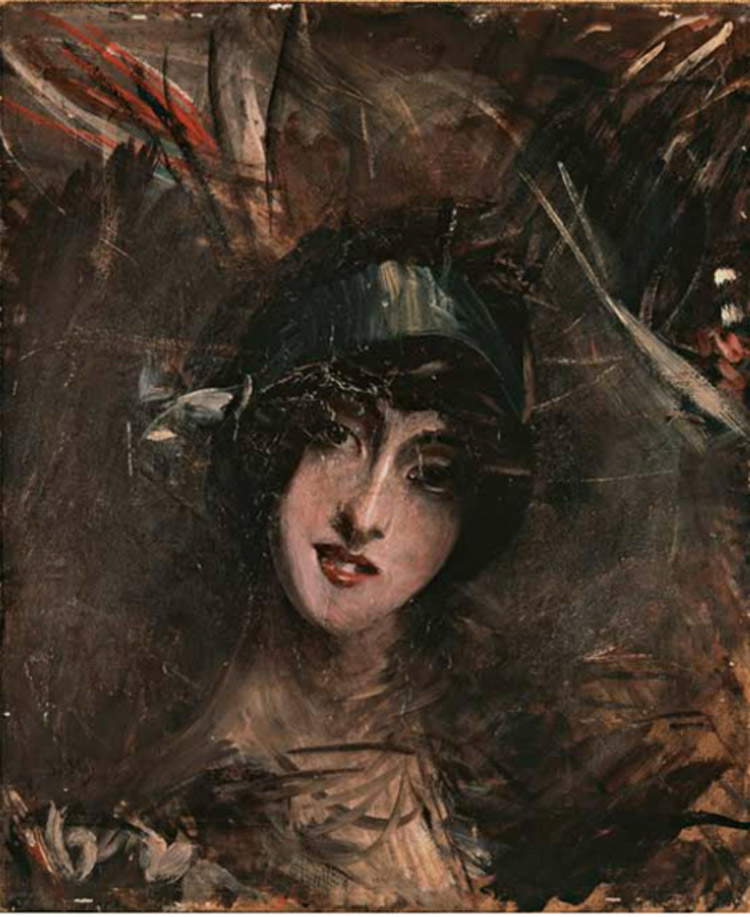

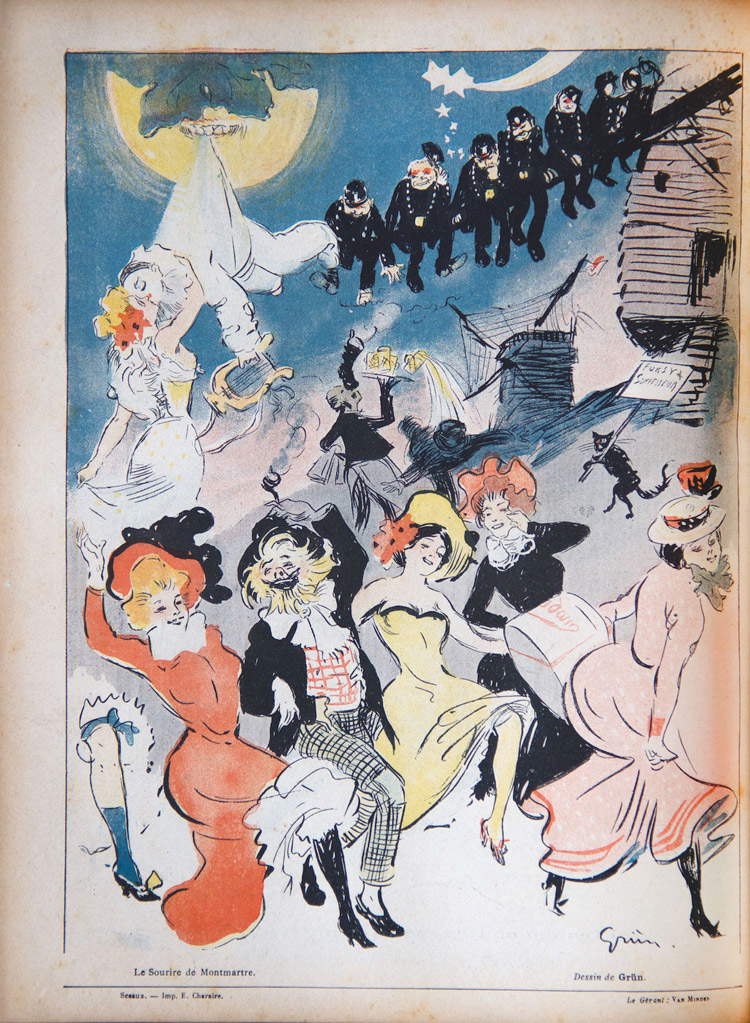

The journey can only begin in France, and evoking the atmosphere of the Paris of the time we immediately find Giovanni Boldini with one of his most famous portraits, the one known as The Little Blue Hat, one of the central paintings of the collection and the exhibition: a close-up portrait, not so usual in the Ferrara painter’s art, shows us a self-confident woman, looking at us with an almost mocking smile, and at the same time denoting an air of coquetry in the movement of her head covered by the blue hat that gives the title to this work often lent to exhibitions on Boldini and his time, and therefore particularly well-known to the public. Boldini’s Madame is accompanied by the graphic works of Paul César Helleu (Vannes, 1859 - Paris, 1923), a friend of the Emilian painter with whom, in the exhibition, he establishes a fruitful dialogue, because also at the center of Helleu’s work are the women of high society in early 20th-century Paris, with their furs, their fanciful and colorful headdresses, and their desire for freedom. An examination of the Parisian milieu of the time would not be complete, however, without the illustrations from magazines (such as LAssiette au Beurre, La Vie Parisienne, Le Sourire, Le Frou Frou, LEclipse, La Lune Rousse), which in Pieve di Cento also include a rare specimen of Le Rire with illustrations by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (Albi, 1864 - Saint-André-du-Bois, 1901) who, as is well known, devoted much of his activity to this particular art form, and without a few works highlighting the contradictions of the time: this is thought of in Adolphe Willette ’s Seven Deadly Vices (Châlons-sur-Marne, 1857 Paris, 1926), a work that launches a critique against the double morality of the time.

|

| Giovanni Boldini, Il cappellino azzurro (1912; oil on canvas, 46 x 55 cm; Pieve di Cento, Museo MAGI 900) |

|

| Jules-Alexandre Grün, Illustration for Le sourire de Montmartre |

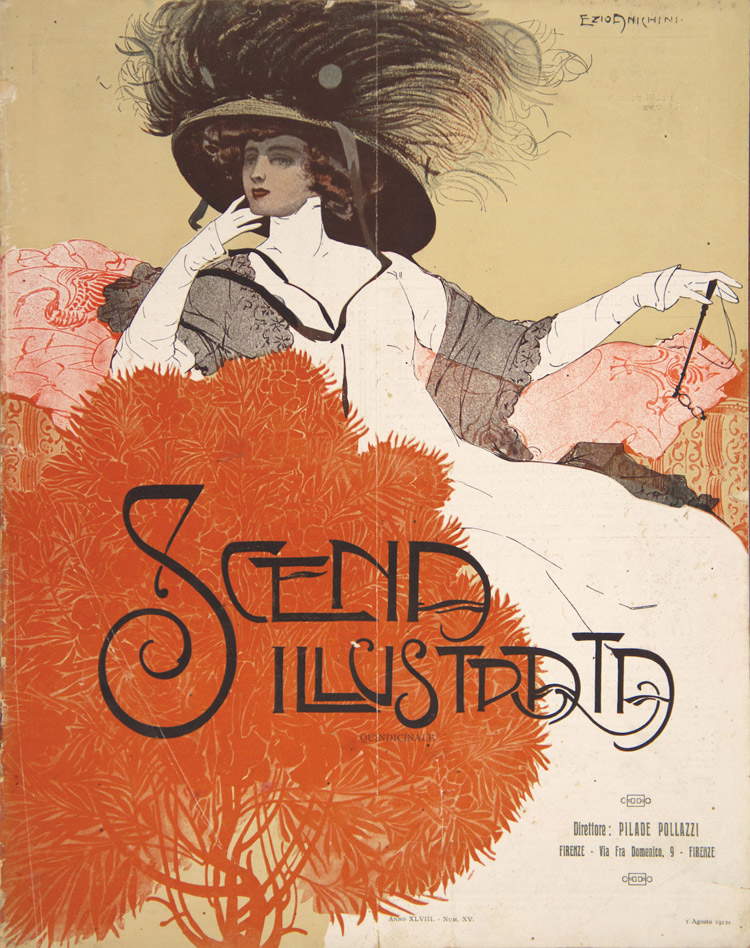

A strong charge of social criticism also emerges from the works of Aroldo Bonzagni (Cento, 1887 Milan, 1918), an excellent painter with a very short parabola and a refined caricaturist whom Giulio Carlo Argan spoke of as the Italian Toulouse-Lautrec. One of his paintings reproduced in the exhibition, Mondanità , has been called the Fourth Estate turned upside down: a group of haughty aristocrats on their way to the theater strolls toward the viewer showing off rich clothes and luxurious accessories, evoking Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo’s famous painting but sarcastically and with a hint of bitterness reversing its meaning. A less disillusioned (and more celebratory) reading of the fashion of the time is that of the advertising postersî by Marcello Dudovich (Trieste, 1878 Milan, 1962), which opens the section devoted to the Belle Époque in Italy (i.e., the one where we also find Bonzagni’s works) and which dialogues with the great Art Nouveau elegance of the illustrations by Ezio Anichini (Florence, 1886 - 1948), who often lent his work for the magazine Scena illustrata, and the sweet refinement of the women of Vittorio Corcos (Livorno, 1859 Florence, 1933), present with Al ballo of 1888, a chromolithograph depicting a lady in a white satin dress while holding a voluminous boa tightly around her neck.

|

| Ezio Anichini, Illustration for Scena illustrata, issue 15, Aug. 1, 1912 |

|

| Vittorio Corcos, At the Ball (1888; chromolithograph, 60 x 38 cm; Pieve di Cento, MAGI 900 Museum) |

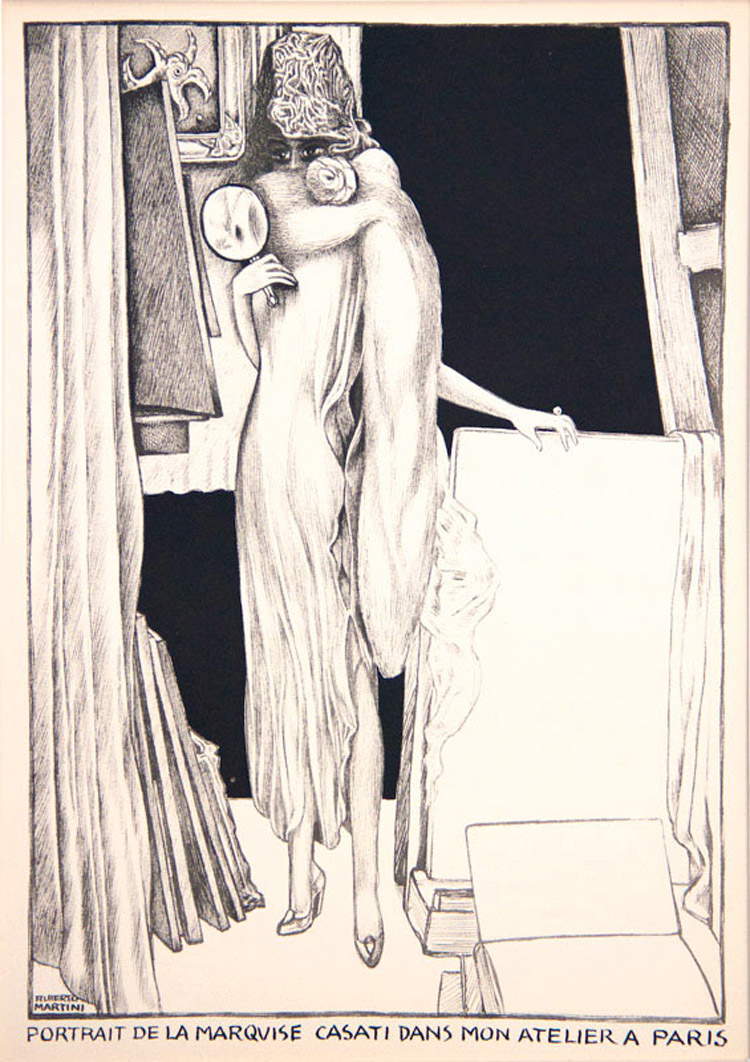

This air of enchantment is then overwhelmed by the more provocative works of artists such as Arturo Martini (Oderzo, 1876 Milan, 1954), who is present with, among other works, an engraving depicting one of the most symbolic and evocative femme fatales of the time, the Marchesa Luisa Casati who, in the print, is depicted in the artist’s Parisatelier while, with a disturbing manner and a mirror in her hand, she approaches the viewer with her face covered by a scarf. Representing the more distinctly sensual side of the Belle Époque are the transgressive and unconventional engravings of the Belgian Félicien Rops (Namur, 1833 Essonnes, 1898) and, to a certain extent, also the albums of the American Charles Dana Gibson (Roxbury, 1867 New York, 1944), who is credited with inventing and subsequently spreading in Europe the type of the Gibson girl, an ideal of a slender, athletic and hips-wearing woman, squeezed into corsets that highlighted her form, characterized by often contemptuous looks and attitudes of superiority towards the man who, in the presence of the Gibson girls, was almost always seen as succubus and ready to satisfy their every desire. A refined yet proud, proud, peremptory woman, a kind of U.S. counterpart to the European femme fatale, but more ironic.

The exhibition is closed by the works of artists from the Germanic area, such as Gustav Klimt (Vienna, 1862 Neubau, 1918), whose famous cover of Ver sacrum, a work published in 1898 and considered germinal for the Viennese Secession, is featured, or such as Ferdinand Reznicek (Vienna, 1868 Munich, 1909), an illustrator who was among the main protagonists of that season. Finally, MAGI900, in closing the exhibition, exalts the figure of Lutz Ehrenberger (Graz, 1878 Saalfelden, 1950), an Austrian artist whose several tempera paintings were purchased by the Emilia museum: in Ehrenberger’s work, too, a prominent role is played by women. The imagery of this still little-known painter and illustrator, who sojourned in Paris on several occasions, frequenting its clubs and traversing its nightlife, is populated by slender but proud and emancipated female figurines, who dance, dabble on stages, celebrate and revel in the company of men, laugh and joke, often overstepping boundaries but never falling into triviality. Ehrenberger’s illustrations, which capture these women with sagacity, savvy and immediacy, also prolong the atmosphere of the Belle Époque beyond the first decade of the twentieth century, manifesting a desire to recapture that joie de vivre typical of early twentieth-century Paris even after the atrocities of the world conflict.

|

|

| Lutz Ehrenberger, Ballerina with Figure in Red (1929; tempera on paper, 29 x 38 cm; Pieve di Cento, Museo MAGI 900) |

If it is true that in the Belle Époque, as the scholar of nineteenth-century France Máire Cross has recently written, it is necessary to discern the prodromes of feminism in the second half of the twentieth century and, above all, it is necessary to observe a turning point in the path of women’s emancipation, the art of the time contributes a strong and immediate image of these transformations. And with its Homage to Femininity, MAGI 900 intends to offer a particular reading of art at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, without neglecting the production of local artists (such as Remo Fabbri and Antonio Alberghini) and offering a lively overview of how the big names measured up to the novelties of an era of great changes, destined to make its echo felt even today, and which is still capable of exerting considerable fascination on the public.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.