Curzio Malaparte, in his Maledetti toscani, said that the libeccio is not a home wind. It is the humid, hot wind that comes from the southwest: it blows especially in summer, rises suddenly, lashing the coast with violent gusts that cut the breath, scatters desert sand over everything it encounters, agitates the sea to the point of causing strong swells. “It pounces like a battering ram on the scattered waves, mussels them, rallies them, pushes them, similar to a flock of baleful sheep, against the white shores, the purple cliffs, the coal-black piers,” Malaparte writes.

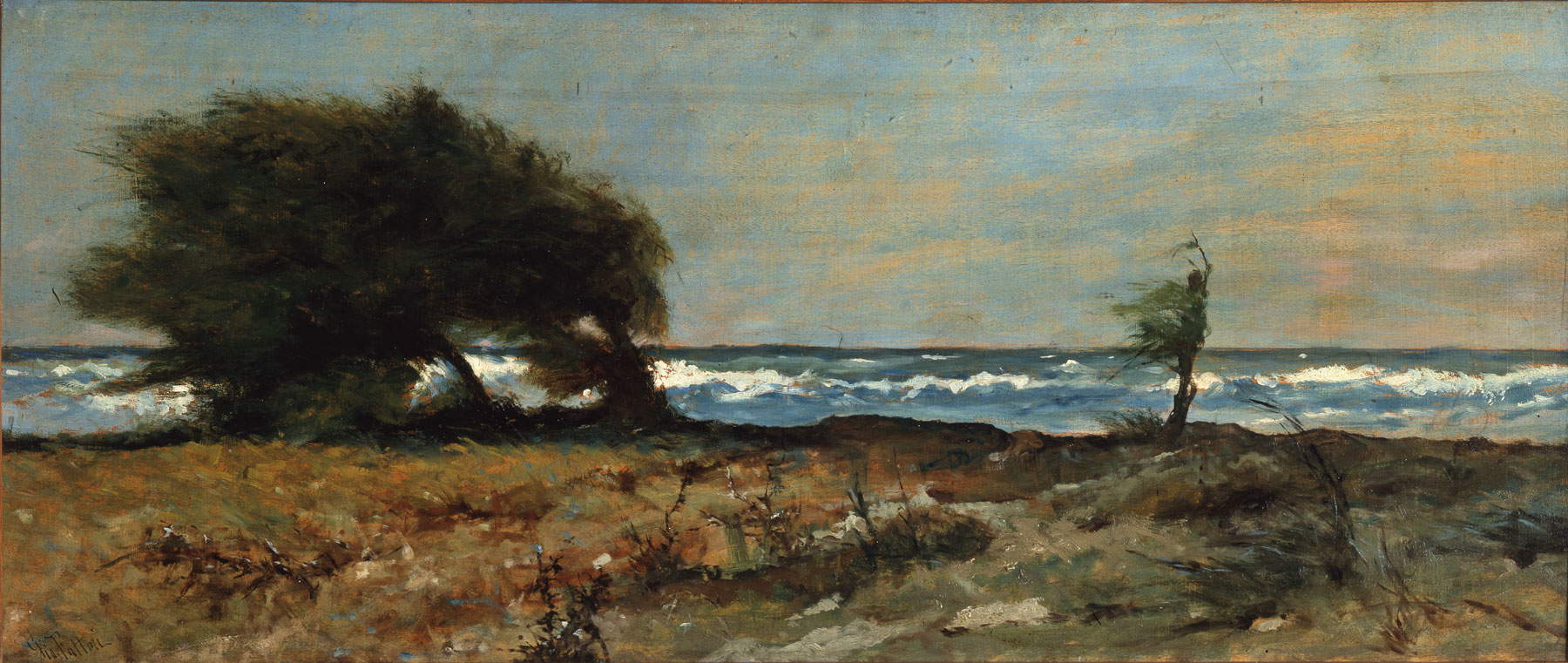

On the coast of Tuscany, where the inhabitants are well acquainted with the libeccio and the consequences of its action, the often unwelcome visits that this wind makes on the shorelines are called “libecciate”: and a libecciata is the one that Giovanni Fattori, a Macchiaiolo and Tuscan of the coast, painted in one of his panels from the 1980s, which is now in the Gallery of Modern Art in the Pitti Palace in Florence. Admired there is a stretch of coastline near Livorno, Fattori’s hometown: it is the coastline of Antignano, just south of the city center, a neighborhood now incorporated into 20th-century urban sprawl, but which in Fattori’s time was nothing more than a village carved out of the ramparts of an old Medici fortress, around the small church of Santa Lucia. Fattori went there often because the stretch of coast from Antignano to Castiglioncello, another place dear to the painter, is one of the most beautiful in Tuscany: the narrow sandy shores that accompany the last glimpses of the town give way to steep cliffs that plunge into the sea, to slabs of sandstone where dense heather bushes cling, to small coves hidden among the inlets and beaten by the waves, to promontories on which, here and there, a few solitary pines or isolated tamarisk trees stand guard over the shoreline.

And the tamarisk that Fattori paints in his Libecciata is still there in its place, alone above a stunted expanse of stones, sand and gravel lying on a rock, watching the sea ripple, a piece of nature resisting the assault of the city behind it. The artist catches her as she is bent by the libeccio (south-westerly wind) that, punctual as every summer, has appeared on the Tuscan coast. All the shrubs that have sprouted from the sand are bowed down by the wind, the sand rises, the sea begins to ripple and whiten, the air swells with saltiness, and the sky begins to cover itself with the first milky veils of the “silvery haze” that “rises from the shores and cliffs, invades the cities, the suburbs, spreads across the countryside.” the libeccio has taken over the coast and is unleashing its fury. Here is that wind which, Malaparte continues, “drops like a hawk on the sails, and tears them: flaps of sail fly away in the whirlwind, like doves. Its long, angry hiss, sharp as a sickle, cuts through the grass of the sea pastures, where herds of horses with frothy manes roar, which the sudden hissing scatters with a gallop over the green sea streaked with long white nitrites.”

|

| Giovanni Fattori, La lib ecciata (c. 1880-1885; oil on panel, 28.5 x 68 cm; Florence, Galleria dArte Moderna di Palazzo Pitti) |

|

| Giovanni Fattori, La libecciata, detail |

|

| Giovanni Fattori, La libecciata, detail |

Fattori painted from life the long, angry hissing of the libeccio. Analyses of the Libecciata, which underwent reflectographic investigations in 2019, have returned the hidden image of a synthetic sign drawn with great speed: the artist concentrated mainly, as one would imagine, on the outline of the coast and the tamarisk, working with the pencil directly on the panel, without any preparation. We seem to see him, Giovanni Fattori, who with a rectangular piece of wood and a pencil in his hand sets off towards the coast of Antignano on a windy day, and there, en plein air, in front of the rocks, he quickly pins this glimpse of landscape on the board, and then finishes the painting in his studio. The elements of the landscape, as is typical of Macchiaioli painting, are defined by large patches of pure color juxtaposed, spread with quick, short brushstrokes, with the colors (the ochre and earthy tones of the sand-covered cliffs stand out here, and the Prussian blue used to evoke the true color of the sea in front of Livorno) also being spreadthem without preparation, directly on the board, so much so that sometimes the artist, in spreading the colors, followed the natural grain of the wood. “Everything I saw, wanted, desired to reproduce,” the artist wrote to Carlo Raffaelli in a letter dated August 16, 1907. “Lacking money and not being able to get an animal, easels and studio, I thought I could study by observing at my pleasure in the streets, and then I emptied and still emptied my little albums with signs; so misery to something is good, strength to observe and draw: all this was at the beginning of my studies.”

Art en plein air, then, as a necessity: a necessity that prompted Fattori to also define himself as a “meticulous observer of the sea in all its phases, for I love the sea because I was born in a seaside town.” Meticulous to the point of transfiguring the Livorno coast into an emotional sensation, ahead of the landscape-state theories of Jean-Marie Guyau and Paul Soriau. In the 1980s, Fattori’s painting inaugurated a new taste for landscape by becoming more poignant and touching, cloaked in lyrical tones and melancholy. The force with which the wind crashes down on nature is almost the image of a restlessness that the artist carried within himself in those years. A landscape as a mirror of the soul, then. But its charm also lies in the contrast of emotions in it. It is not reassuring, but it is a familiar landscape. In 1925, Plinio Nomellini, a favorite pupil and rebel, had to recall the intensity of this relationship Fattori had with the landscapes where he was born and raised, with some words that could well fit to describe La libecciata: “On the bleak beach, where only the tamarisk trees infoliate, his soul felt placated, the libeccio swerved the clouds and the crux of his thoughts, the wave lapping the sandy beat, whispered a lullaby of hope.”

The emotional intensity of this painting is not only the reason for its modernity, making it a masterpiece of European significance, but it is also why we see it hanging on a wall in the Pitti Palace today. In 1908, the painting was in the possession of Giovanni Malesci, a good painter, a pupil of Fattori and his heir: Fattori had passed away on August 30 of that year, and the City of Florence had immediately convened a commission of experts, consisting of Ugo Ojetti, Angelo Orvieto and Domenico Trentacoste, with the intention of purchasing some of the artist’s works to enrich the public collections. On September 15, 1908, the commission produced a report advocating the purchase of "an oil landscape, Libecciata, where even with very simple but precise means, without figures, he has given to a short line of country the same force of expression as to a human face." A landscape, then, that is as alive as a portrait. Or perhaps, like a self-portrait.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.