Between surrealism and homage to Carlo Scarpa: the double abstraction of Michele Chiossi

In his work Le surréalisme et la peinture, André Breton offered the most direct and vivid account about the birth of the game of Cadavre exquis, or the “game on folded paper that consists of having several people compose a sentence or drawing, without any of them being able to take into account the previous collaboration or collaborations,” as per the definition that Breton himself included in his Dictionnaire abrégé du surréalisme, compiled together with Paul Éluard in 1938. The game is said to have originated around 1925, and Breton attributed its invention to Jacques Prévert, Yves Tanguy and Marcel Duhamel, who allegedly came up with it to revive conversations destined to die out. One takes a sheet of paper, folds it, writes a word on it, and passes it on to a companion, who can see only the contribution of the one before him, but not everything that was written previously. Apparently, the first sentence to spring from the game was the now-famous “Le cadavre exquis boira le vin nouveau” (“The exquisite corpse will drink the new wine”). For Breton, the Cadavre exquis was an “infallible means” of giving free rein to the activity of the spirit, freed from constraints and conventions of all sorts. A spontaneous association of elements, provoked by the evocative power of words and images, in line with Surrealist research on thatpsychic automatism that was supposed to express the functioning of thought.

It is to these experiences that Michele Chiossi (Lucca, 1970) refers when he presents me with his latest work, which he has brought to an exhibition in Carrara, at Palazzo Binelli. It is a large sculpture, more than two meters high, composed of the most varied elements. He entitled it Marble Exquise, he explains to me, just based on the surrealist idea of the juxtaposition of very distant and different materials. And here we have marble, wood, wind, lace. On marble and wood, the questions are not many: Michele Chiossi is a sculptor, and for this work he used two materials of millennia-old tradition. More curious, however, is to know where he got the idea of creating this cabinet introduced by two lace curtains gently moved by a breeze powered by some hidden fans. The artist is fascinated by the material, and with a certain deference he intends to evoke the places where the marble comes from: the quarries of the Apuan Alps, often swept by the wind rising at high altitudes. But the game of Cadavre exquis continues. The Surrealist psychic automatism must have brought to Michele Chiossi’s mind the opening scenes of Luchino Visconti’s The Leopard: “I was reminded,” he tells me, “of the prayer scene at Donnafugata behind the windows of the palace: the windows are open, there is wind, the wind moves the nineteenth-century lace of the curtains.” And it also involved a lot of research, because Michele Chiossi also set himself the goal of being philologically unimpeachable: "I went to look for early 19th-century Calais lace. I then did color baths to create chromatics that were as close as possible to the original ones. And with the wind moving them, I really tried to evoke the Leopard sequence." Turning to the side, you will notice, stamped on the side, on the wood, the title of the work, in characters reminiscent of the branding used in the food industry. It is a kind of connection with the traditions of our country. "I liked to give this character of branding impression. When I started working in the 1990s in New York, I began to reread our culture through food as well. I wanted to reconnect with that experience, I thought about the lettering of Parmesan cheese, and so I created these burns with a kitchen brûleur."

|

| Michele Chiossi, Marble Exquise (2017; Breccia Capraia marble, wood, steel, fans and lace, 220 x 140 x 60 cm). Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte. |

|

| A photogram from the opening sequence of The Leopard. |

In the critical text that accompanies the Carrara exhibition at Palazzo Binelli(Carrara Subabstraction the title, organized by Nicola Ricci Contemporary Art), critic Marco Bazzini notes how Marble Exquise is also inherent in that double abstraction that characterizes all the works on display. The first level is that of the curtain, which with its weave constitutes ageometric abstraction. And then there is the marble, with its veins that give rise to an“organic” abstraction. An abstraction that leads our imagination to see, in those veins, everything that our imagination suggests to us: clouds, landscapes, characters, stories, maps. It is again our unconscious that drives the experience and makes abstraction a highly subjective thing. A double abstraction that can have more than one valence: it can be a way to offer the observer a key, willingly also rather ironic, in order to look with a different and renewed eye atabstract art of all ages. One can catch a glimpse of the idea, in rather nouveau realiste taste, of inserting a sort of gate through which to provide a spur for the observer’s imagination to picture its own marble landscapes. It can be a way of opening mental but also physical windows, with an effect accentuated by the concrete and recurring presence of the curtains and gates. It is a very lyrical, poetic pursuit, one that lets a great sensitivity shine through. “My fellow painters,” Michele Chiossi continues, “have always told me that for them the painting is always a window that can also become a space on the wall. And this space opens windows through which to observe a world made up of everything that can be seen and interpreted.”

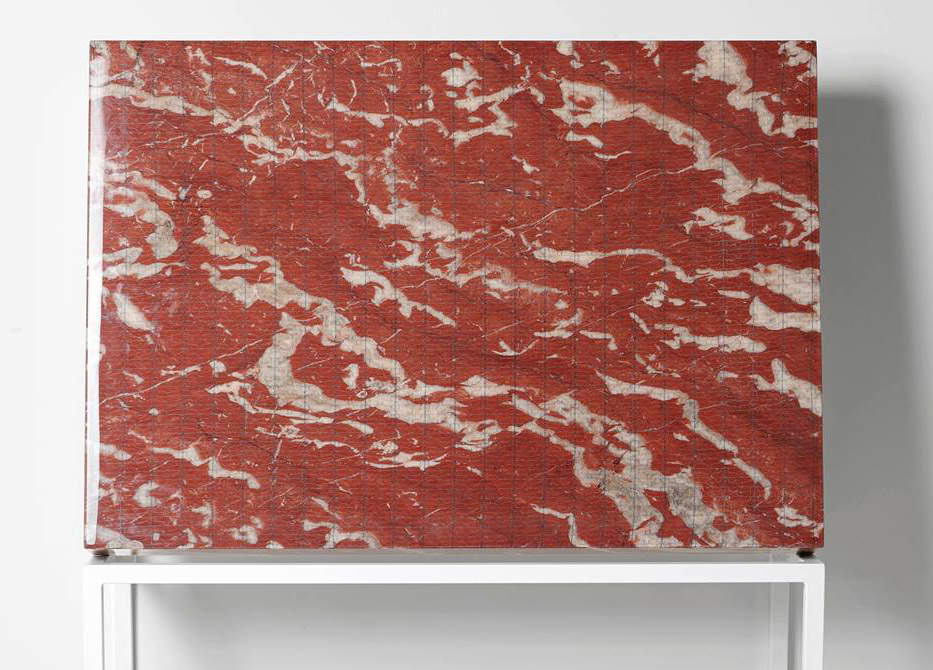

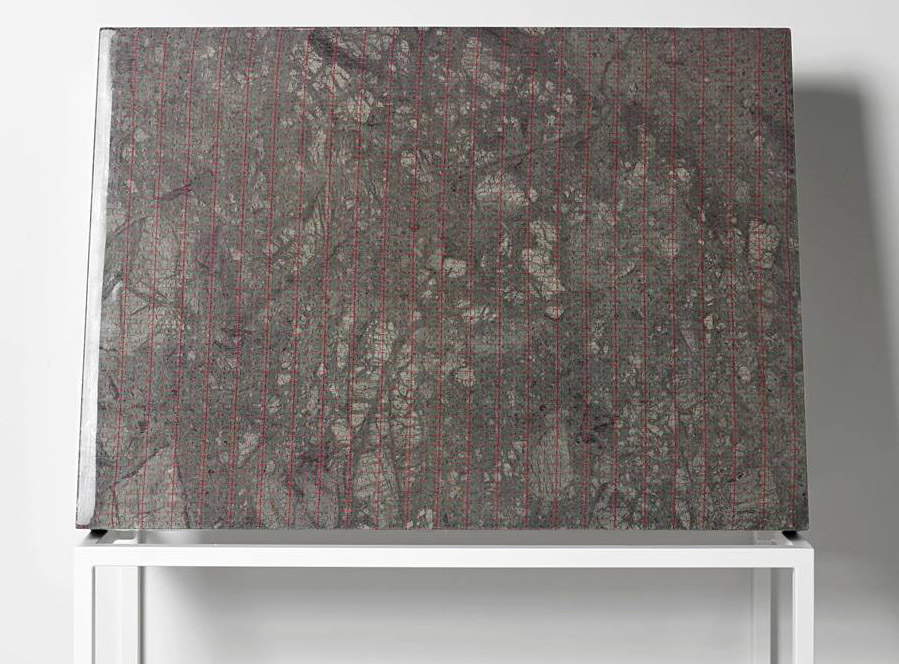

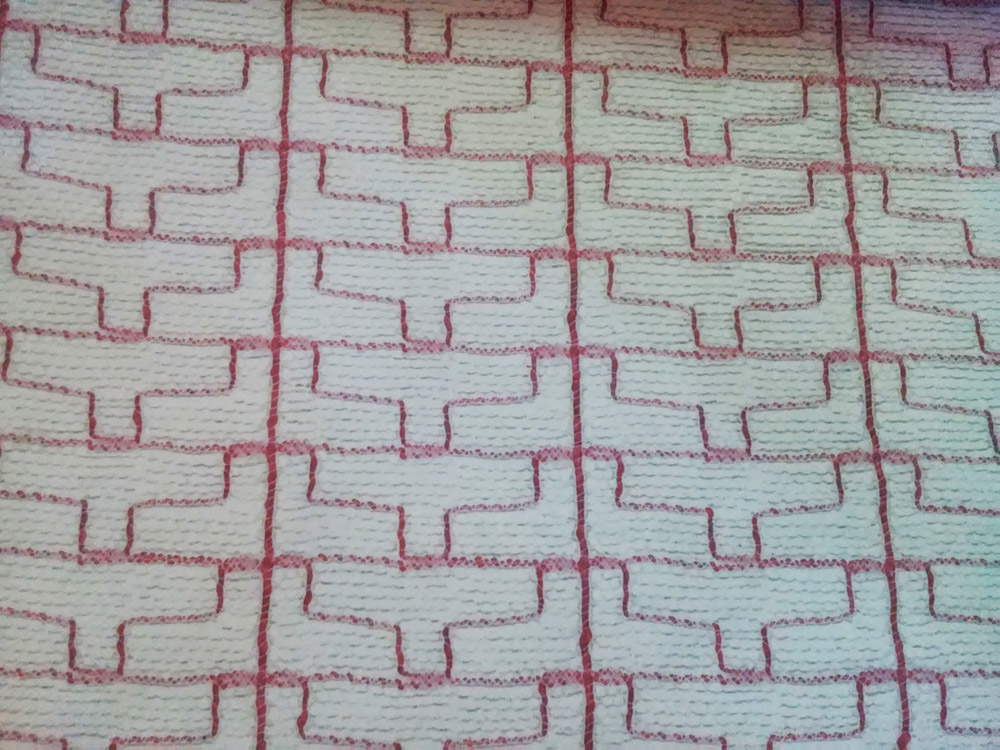

All the works in the Subabstraction series are nothing more than thin slabs of marble, ten centimeters thick, and wrapped in these laces with regular geometric texture. One of the typical features of Michele Chiossi’s art (he is used to call it his “trade mark”) is the zigzag line that breaks the contours of his figures and is charged with symbolic meanings that refer to artistic research, creative practice, the co-presence of the ancient and the contemporary, and the multiform variety of our existences. In these works, the zigzag line takes on the appearance of a tribute, because the motif of all of Michele Chiossi’s latest works is none other than the grid that the great Carlo Scarpa designed in 1963 for the water doors of the Fondazione Querini Stampalia in Venice. The architect was called in to refurbish the rooms on the ground floor of the old building that houses the Foundation’s headquarters and was subject to frequent damage from high water. Carlo Scarpa opted for a design that, instead of preventing water from entering the building, would assist the flow of water through a series of bulkheads that would route it into a basin located in the garden at the back of the building. And for the water gates, that is, those that give directly to the canal, he imagined large gates within which to repeat the geometric motif. For Michele Chiossi this is a tribute particularly consonant with his way of making art: his lines find full agreement with the broken lines often used by Carlo Scarpa. The gate of water gates is thus transferred to marbles, specially chosen for their veining, as well as for their colors, which are accentuated by the chromatics of the lace.

|

| Michele Chiossi, Subabstraction - White (2017; Piana Arabescato marble, lace and resin, 100 x 70 x 10 cm). Ph. Credit Camilla Santini |

|

| Michele Chiossi, Subabstraction - Red (2017; Rouge Languedoc marble, lace and resin, 100 x 70 x 10 cm). Ph. Credit Camilla Santini |

|

| Michele Chiossi, Subabstraction - Green (2017; Verde Guatemala marble, lace and resin, 100 x 70 x 10 cm). Ph. Credit Camilla Santini |

|

| The geometric motif |

|

| Carlo Scarpa, Water Doors at the Querini Stampalia Foundation (1963) in 2014 on the occasion of the Carlo Scarpa exhibition. Photo credit. |

“I did not want to analyze marble from a sculptural point of view,” the artist elaborates, “but I wanted to observe the soul of marble, its most intimate nature, and I wanted to detect it.” He shows me a diptych composed of two squares of marble forty centimeters on each side, one mauve and the other sage in color. “Here I wanted to make the color of the marble that can be seen through the weave of the lace even more evident, and to do this I used special color baths, which I chose personally, so as to also accentuate certain effects of the veining, as well as the color of the material.” And then there are the drawings, where again this idea of layering recurs: the motif of the scarp grid, shown in gold and silver on sheets of tracing paper, is superimposed on photographs of marbles that are also heavily veined. The effect that is achieved is similar to that of the sculptures.

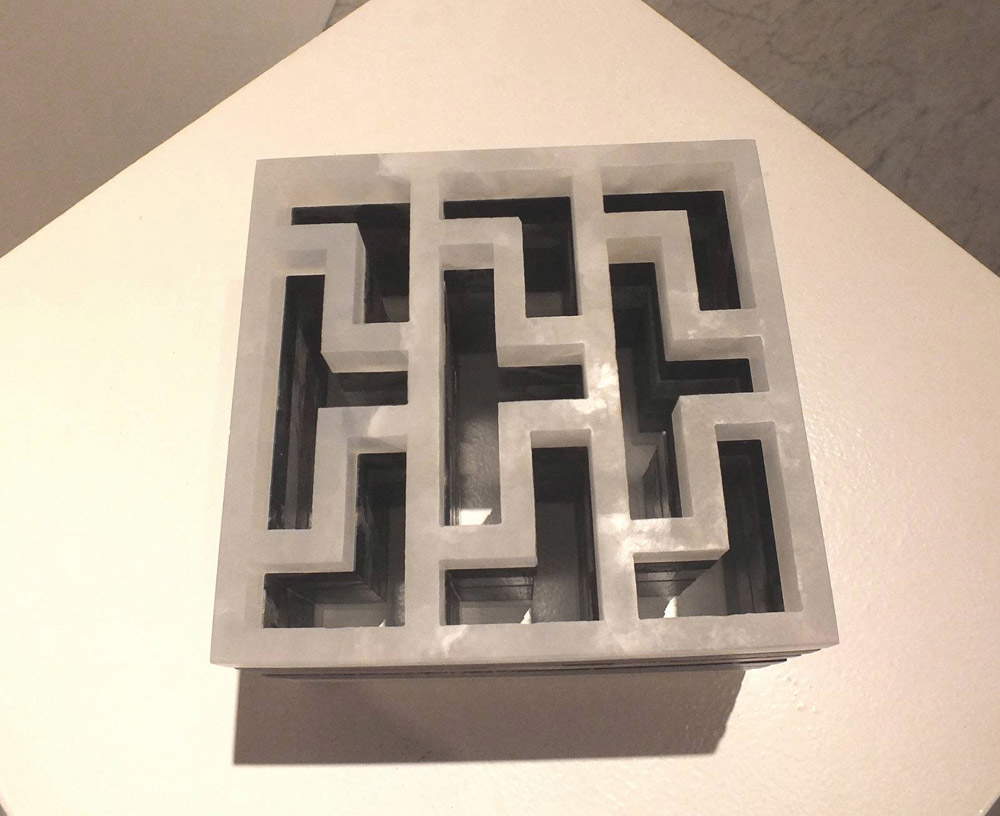

Michele Chiossi then gathers my attention to one last work, a kind of decomposable marble cube, composed of several levels, symbolizing the artist’s work, as an allegory of the different levels of reading that can be given of a work, but also of the various technical stages of material processing. He called it Portego Policromo and it is therefore a sculpture that, even in its title, pays homage to Carlo Scarpa. The “portego” the artist has in mind is that of the Fondazione Querini Stampalia, which is accessed through the gates mentioned above. And the motif is again that of Carlo Scarpa’s grid. There are six overlapping levels, all in different materials: there is a statuary marble, a Rosso Levanto, a Rouge Languedoc, a Portoro, a Verde Guatemala, and there is also a white alabaster level. He takes one in his hand and puts it in front of his eyes, “this sculpture is a small architecture to show a world through Carlo Scarpa’s grid.” I also see in it a contemporary reading of thattotal art that was characteristic of Baroque culture. Michele Chiossi set himself the problem of also being a painter and an architect. The marbles of the Subabstraction series, for him, are paintings in their own right. The motif of ornament is of architectural descent, so much so that it becomes architecture itself in the Portego Policromo. And the so consistent achievement of such a unity, capable of annulling distances with a certain degree of spontaneity, is but one of the clues that reveal all the culture and intelligence of one of the most talented and up-to-date Italian sculptors on the contemporary scene.

|

| Michele Chiossi, Subabstraction - Mauve (2016; Breccia Capraia marble, lace and resin, 40 x 40 x 4 cm) and Subabstraction - Sage (2016; arabesque marble, lace and resin, 40 x 40 x 4 cm) |

|

| Michele Chiossi, Portego Policromo (2017; statuary Carrara marble, Rosso Levanto marble, rouge Languedoc marble, Portoro Extra marble, Verde Guatelama marble, alabaster, 18 x 19 x 12 cm). Ph. Credit Nicola Ricci Contemporary Art |

|

| Michele Chiossi shows the Portego Policromo. Ph. Credit Nicola Ricci Contemporary Art |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.