Between Reality and Desire. The homosexual imagery of Jean Cocteau's drawings.

It sounds perhaps a little strange, to those who were to leaf through Jean Cocteau’s The White Book today, the idea that the author of this singular tale, somewhere between autobiography, novel and confession, does not use precise terms to define his own homosexuality, nor does he hint at the slightest claim or declaration of his orientation, however clear it obviously appears from those pages composed with such ardor, such poetry. The White Book (Le livre blanc) is one of the first autobiographical writings in the history of literature in which the author traces the origins and development of his own homoerotic feelings. It is not the first ever: one only has to think of André Gide’s If the Grain Doesn’t Die , which precedes The White Book by four years, although there are many differences that divide the two works: Gide’s is an account of all the writer’s first twenty-six years, while Cocteau’s book is nothing more than an account of his erotic experiences. However, it is possible to regard it as one of the cornerstones, one of the most brilliant manifestos of homosexual literature, for several reasons. The absence of any literary pretence or disguise. Its character as an autobiographical novel in which each story revolves around the discovery, and then the realization, of one’s sexual orientation. The frankness with which Cocteau confesses to himself and to readers his own inclinations, the disturbances that result from this condition, even to the idea of seeking solace in spirituality, except then coming to the conclusion that it is not possible to escape oneself, and that not even society can reject a man who is part of it simply because his nature is different from that which someone has elevated to canon (“this book,” Cocteau writes in the finale, “will perhaps help to understand that by exiling myself I am not exiling a monster, but a man whom society does not allow to live because it considers him an error in the mysterious gears of the divine masterpiece”).

It is hard not to consider, reading the author’s conclusions, The White Book also as a book of denunciation, although perhaps Cocteau did not have this understanding: the idea that the title derives from the use of employing the expression “white paper” to refer to a political report that includes lists of actions or information on a given subject can only seem anachronistic, since the use of the term white paper first appeared in 1922, and certainly had not yet entered common usage at the time Cocteau published his account. Or if not as a book of denunciation, The White Paper could nonetheless be considered a writing from which some form of contestation shines through: in the finale, Cocteau indulges in the same remarks that, three centuries earlier, Salvator Rosa entrusted to his Satires (“quel che aborriscon vivo, aman dipinto”): “This is the time of murderers,” Cocteau writes, “and young people would do well to remember the phrase ’Love must be reinvented.’ Dangerous experiences, the world accepts them in the field of art because it does not take art seriously, but condemns them in life.” Yet despite the assumptions, the book came out almost hidden. It was first published in 1928, “white” as per its title, that is, without illustrations, with only the title on the cover, and even anonymous. Only two years later, in a new publication for Editions du Signe, would the book, though still anonymous, come out with some illustrations. And never would Cocteau claim autograph authorship of the book, although he agreed, at the end of his career, to have it included in his opera omnia.

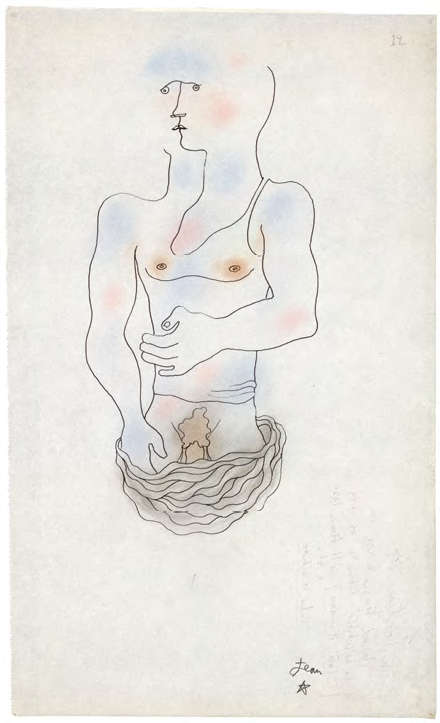

The monographic exhibition that the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice has dedicated to Jean Cocteau (April 13 to September 16, 2024, curated by Kenneth E. Silver) has brought together a couple of studî for Le livre blanc, along with a rather large number of folios from other periods into which the artist, we can think, nonetheless pours some of the imagery that innervates the book. “These are,” Silver explains referring to the illustrations for Le livre blanc, “beautiful and evocative drawings, not ’realistic,’ images of young men entwined and entwined, where body parts are often broken up: a mixture of sensitively drawn outlines and blurred passages.”

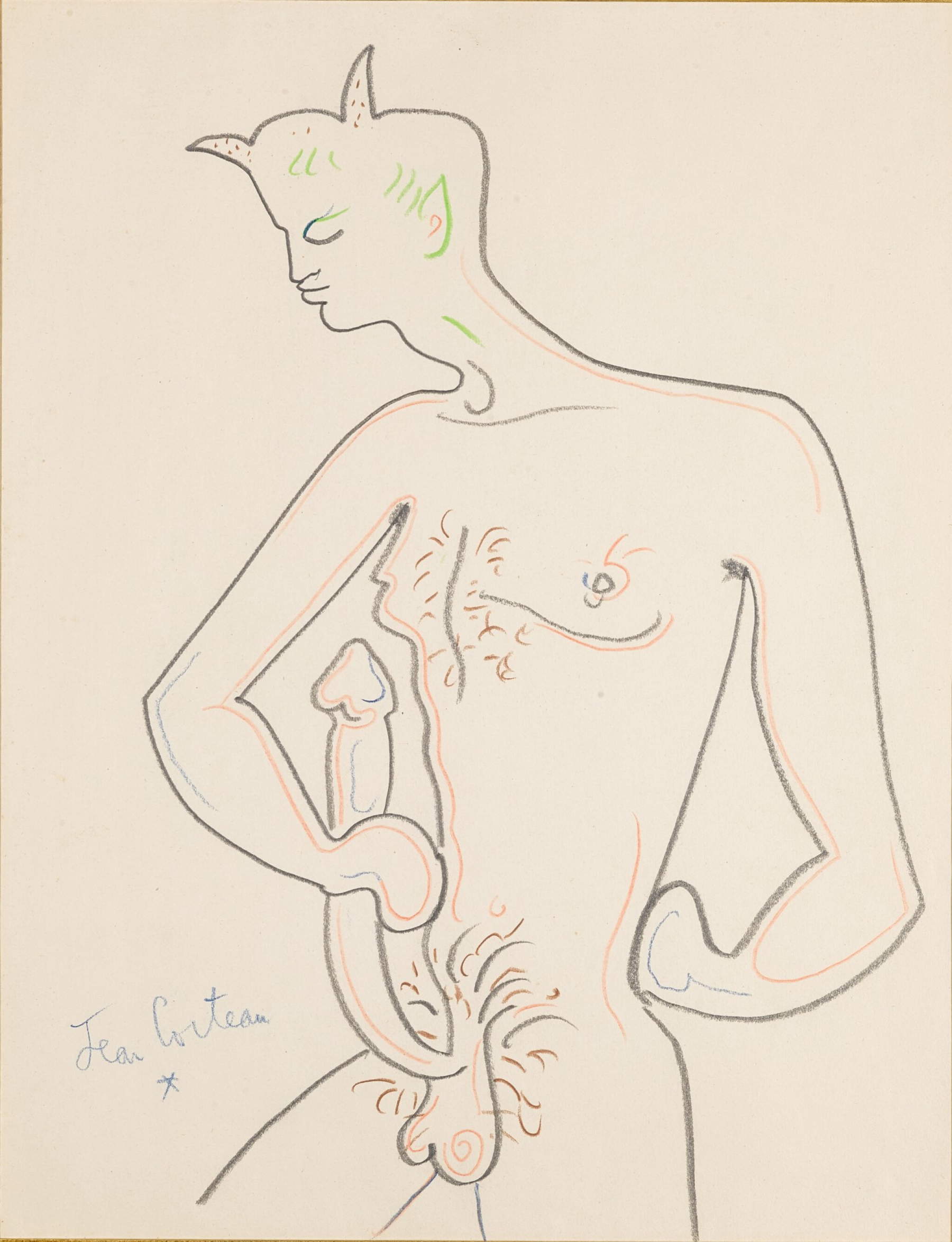

It was with the illustrations for The White Book that Cocteau first ventured into the depiction of a “visually abstract” homosexuality, as Silver calls it, followed later by “decades of realistic drawings of various kinds, all quite explicit,” beginning with those executed to illustrate Jean Genet’s Querelle de Brest . Of course: even the images for The White Book, while less loaded and less bold than those Cocteau would later sketch, do not leave much room for the imagination and are often a faithful visual translation of the frank and forthright language with which the artist speaks of his homosexuality in the book, although the figures, to the viewer’s eye, almost seem to float in a dreamlike aura. Cocteau’s drawings move in the space of a reverie that mixes abstraction and figuration, where the use of decompositions rooted in Cubism is functional in mixing (but at the same time also separating) the narrator’s body with that of the book’s characters, and leaving room for an ambiguity that amplifies that which transpires from the pages. Cocteau himself, after all, had described himself as “a lie that always tells the truth.” If in reading The White Book one finds oneself enveloped in the credible tale of a formative journey, a sort of initiation into homoerotic love described with sincerity and ease by an author who, however, does not fail to mix fact and fiction (for example, the real Cocteau as a young man ran away to Marseilles and not to Toulon where some of the most daring daring events of the novel) and avoids presenting itself to the reader by exhibiting even the slightest vindication; with the illustrations, the reader is left with the added inconvenience of figuring out whether the story that melts before his eyes is reality or dream, is life or confessed fantasy, is an account of an experience or a projection of desire. The very young Dargelos, Cocteau’s schoolmate, the first boy with whom the author falls in love, unrequited (he will later die under tragic circumstances), is drawn in the grip of two bare legs that are not matched in the novel and should, if anything, be read as the translation of’an obsession of Cocteau, who even as a young adult would see the image of that long-dreamed of boy again in the faces of the lovers he would meet in his life.

There is no shortage, however, of more pointed correspondences between the imagery of the illustrations and that of the novel. The episode of the glace transparente, the “transparent mirror,” the glass that, in the novel, divides the hall of a public men’s bathhouse into two rooms, and on one side is treated as a mirror while on the other is transparent allowing those in one room to look at those in the other without being seen, seems to be more of an erotic fantasy than a description of a real experience (“One of my only regrets was the transparent glass. We sit in a dark booth and open a shutter. This shutter reveals a metal canvas through which the gaze embraces a small bathroom. On the other side, the canvas was a glass so reflective and smooth that it was impossible to guess that it was full of gazes. For a few pennies I could spend Sunday there. Of the twelve mirrors in the twelve bathrooms, it was the only one of its kind. The boss had paid a lot of money for it and had it flown in from Germany. His staff was not aware of the observatory. The working youth served as a show. Everyone followed the same program. They would undress and carefully hang up their new clothes. [...]. Standing in the bathtub, they would look at each other-they would look at me-and begin with a Parisian grimace that showed off their gums. Then they would rub one shoulder, take the soap, get soapy. The soaping would turn into a caress. Suddenly their eyes would leave the world, their heads would fall back, and their bodies would spit like furious animals. Some, exhausted, would let themselves melt into the steaming water, others would begin the maneuver again [...]. Once, a Narcissus who was enjoying himself brought his mouth to the glass, stuck to it and carried on the adventure with himself to the end. Invisible like the Greek gods, I pressed my lips against his and imitated his gestures. He had never known that instead of reflecting, the glass acted, was alive and had loved him.”). There: those drawn images, so delicate, almost aerial, of bodies merging, of young men uncovering their genitals and beginning to touch each other, even that of the naked peasant on horseback who represents for Cocteau the first contact with his own homosexuality, seem to have more to do with the invisible than with the visible, they are glimmers within a fog that combines memories, cravings, projections, they offer the viewer the sensation of’a fuzzy tangle where the boundary between fiction and reality is as blurred as the one that separates the Cocteau of the mirror from the boy in front of whom he masturbates, leaving the reader to wonder about the actual concreteness of that experience (“Aestheticism in Cocteau is often expressed through the image of the mirror,” scholar Richard Dyer has written: “Mirrors aestheticize because they frame fragments of reality, which they return on a shimmering, one-dimensional surface: they transform reality into beautiful images.”).

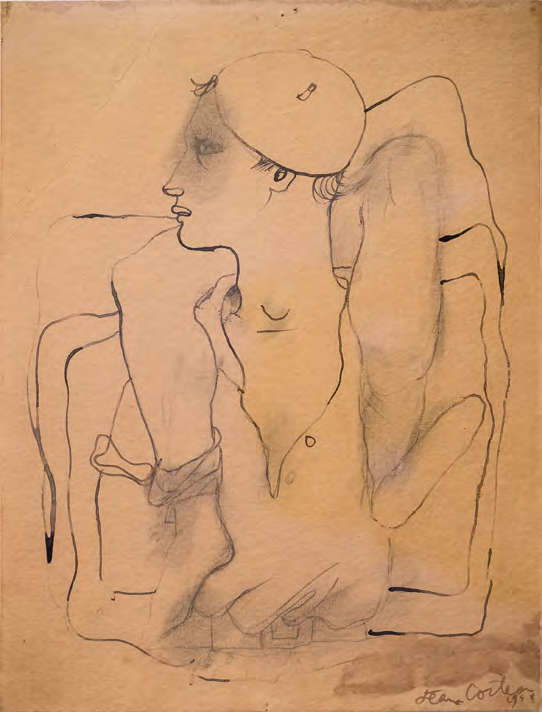

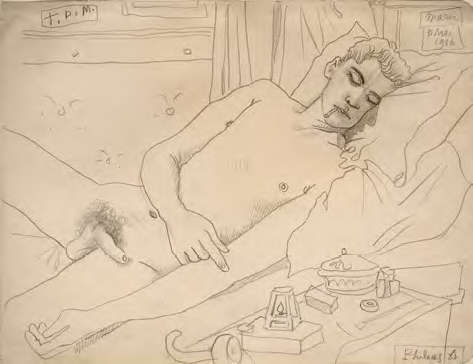

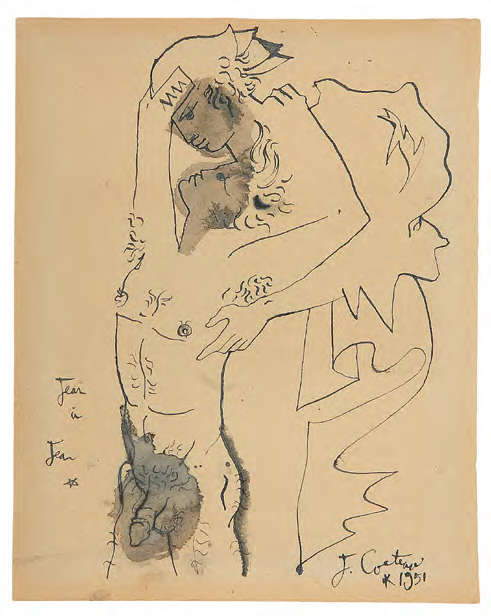

The drawings that Cocteau would produce after that first illustrated edition of the White Paper do not have the same dreamlike character: while drawing from the same imagery, they appear decidedly more descriptive. The Venice exhibition rounded up a good number of them: Two naked lovers in bed, their genitals well described, their pubic hair minutely outlined, depicted spooning (a pair of sailors for Genet’s Querelle de Brest ), and then again the portrait of Édouard Dermit, Cocteau’s lover, depicted naked in bed, or the Deux hommes enlacés “Jean à Jean” (a double portrait of Cocteau himself portraying himself together with his partner, actor Jean Marais), not forgetting the intense portrait of lover Marcel Khill depicted naked, in bed, smoking opium. “It is difficult,” writes Kenneth Silver, “to overestimate the impact of this body of work on Cocteau’s contemporaries and on gay men in general from then on: there is nothing comparable, no other queer male art form so seductively produced by a major figure of the avant-garde, Parisian or otherwise.”

![Jean Cocteau, Erotic Scene (Sleeping Nude) (Scène érotique [Nu endormi]) (ca. 1937-1939; ink on paper, 26 × 21 cm Basel, Kinzel-Schilling Collection) Jean Cocteau, Erotic Scene (Sleeping Nude) (Scène érotique [Nu endormi]) (ca. 1937-1939; ink on paper, 26 × 21 cm Basel, Kinzel-Schilling Collection)](https://cdn.finestresullarte.info/rivista/immagini/2024/2663/jean-cocteau-scena-erotica.jpg)

![Jean Cocteau, Couple of Sailors (Querelle de Brest) (Couple de marins [Querelle de Brest]) (1947; graphite on paper, 27 × 21 cm; Brussels, Kontaxopoulos Prokopchuk Collection) Jean Cocteau, Couple of Sailors (Querelle de Brest) (Couple de marins [Querelle de Brest]) (1947; graphite on paper, 27 × 21 cm; Brussels, Kontaxopoulos Prokopchuk Collection)](https://cdn.finestresullarte.info/rivista/immagini/2024/2663/jean-cocteau-querelle-de-brest.jpg)

A direct, explicit eroticism, which not infrequently finds references in the art of the past, both when Cocteau employs the written word (an example of this is the glass episode itself, in which the young man who s’attaches himself to the mirror is compared to a novel Narcissus), as well as when he resorts to drawing (it is hard not to see in Édouard Dermit’s nude portrait of Édouard Dermit some echo of the Barberini Faun, or a kind of homosexual translation of Canova’s Cupid and Psyche in the portrait Jean à Jean): myth served Cocteau to investigate reality beyond its visible and tangible aspects, as well as to conceal, at least in part and according to refined devices, his own homoerotic desire, leaving the audience with the task of decoding it. An eroticism that, read through the drawings Cocteau executed for the first illustrated edition of the White Paper and those he would later produce from the late 1930s onward (and particularly those from the 1940s and 1950s) also helps us to understand how the artist had to perceive his own homosexuality during his lifetime.

It was scholar Frédéric Canovas who highlighted this difference in perception. From the writing of the White Paper, we get the idea of a Cocteau torn between the need and desire to know himself and the difficulty of expressing, if not achieving, this knowledge. Canovas notes how Cocteau expresses this homosexuality, in the White Paper, with terms such as “ignorance,” “blindness,” “wave,” and “mystery.” a preoccupation, an absence, something of which the artist is aware but perhaps cannot fully comprehend, a reason for which, in the end, he will try to resort to the help of his own spiritual dimension, only to conclude with the final realization, which takes the form of the awareness of’a society that rejects homosexuals (a rejection, a contempt that Cocteau also had to suffer personally, even in his own artistic milieu, given the obstructionism that André Breton opposed against his presence in the Surrealist group: “I accuse the pederasts,” Breton wrote in 1928, “of proposing to human tolerance a mental and moral deficit that tends to configure itself as a system and paralyze all the societies I respect.”) Perhaps, even the drawings of the 1930s are to be read on the basis of this elusive self-perception.

The sheets of the 1940s and 1950s are those of the Cocteau who, on the other hand, better grasped the contours of his own orientation: an awareness that would later result in the publication, in 1947, of La Difficulté d’être, another autobiographical writing in which the artist emphasizes how his homosexuality should not have meanings and consequences for his position within society. “Blindness, instinct, confusion and lack of form, once perceived as curses,” Canovas writes, “are now considered positive and pleasant aspects of homosexuality.” The characters who populate Cocteau’s later drawings, beginning with those accompanying the 1949 edition of the White Paper, appear satisfied, fulfilled, perhaps even proud; their bodies take on a more definite material texture but above all they demonstrate a maturity that is instead difficult to find in the works of fifteen to twenty years earlier. They embody what Cocteau calls “strength in love with strength,” or, Canovas explains, “a more positive but also more idealistic and narcissistic vision of homosexuality.” Hence also the more markedly sensual character of the late drawings, the absence of any form of censorship, the uninhibited and unfiltered eroticism, sometimes bordering on pornography. However, it should be noted that Cocteau would never have exhibited, or in any case allowed public dissemination of, the more racy drawings: he evidently did not feel ready, or felt that the public was not yet ready to deal with similar figurations. However, the editorial history of the White Paper, to be read in parallel with the evolution of his drawings, makes it clear how Cocteau used the images, as Canovas has written, to “’rewrite’ his story and give it a new twist or at least a more positive tinge.” Cocteau’s drawings tell the story of a man who tried on several occasions to change the way he declared his homosexuality. The white paper could not be rewritten, and it should be reiterated, however, that Cocteau, throughout his life, would refuse to explicitly acknowledge its authorship. The illustrative apparatus could, however, be modified, and probably the transformation of the images reflects the change of position that Cocteau took regarding his own homosexuality, a position that, in his mature years, would prove to be more conciliatory with his own past, less guarded, decidedly more proud, aware that those homophobic resistances that the artist was always forced to face, and which remain to this day the most plausible explanation for his choice to publish The White Book anonymously, were beginning to grow weaker. A sign that perhaps the times were maturing as well.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.