There was a time in the history of Italy when putting up a Christmas tree was a custom looked upon with suspicion: it was the 1930s, and Fascism was concerned with discouraging what is perhaps today the most beloved Christmas decoration, on the grounds that it is a custom imported from Nordic countries. Thus, in the fall of 1933, prefects sent circulars to the podestas (mayors, as they were called during the regime’s era) asking local governments to “take care that on the occasion of the forthcoming Christmas and Epiphany festivities city charities and institutions do not use trees to adorn halls or to hang toys, packages, etc. on them.” (thus a circular issued by the prefecture of Parma on November 25, 1933): “As is well known,” it explained, “Fascism is opposed to the Christmas Tree because it is derived from a Nordic custom, introduced into our country out of an ill-conceived spirit of imitation, substituting it for the ’Nativity scene,’ which instead represents a typical Italian tradition.” Disincentivizing the Christmas tree, encouraging the spread of the nativity scene: this is how fascism also intervened in Christmas decorations. And it was in this context that one of the most interesting nativity scenes of the time was created, the Umbrian Nativity by Enrico Cagianelli (Perugia, 1886 - Gubbio, 1938), a work that was presented in 1934 at the International Exhibition of Sacred Art in Rome, where it was awarded a gold medal and 1,500 Lire, and of which today the Cagianelli Center for the ’900 in Pisa preserves some statues and specimens from the run of original casts made between the 1950s and 1960s in the workshop of Gubbio ceramist Leo Grilli, as well as various documentary material.

The 1934 exhibition was the second edition of an event aimed at reviving sacred art in Italy and, at the same time, putting small Italian craft centers in the spotlight: the exhibition also had a section, placed under the auspices ofENAPI, the Ente Nazionale per l’Artigianato e le Piccole Industrie, established in 1925 with the aim of encouraging small industry and craftsmanship. The first edition was held in Padua the year before, and the Roman edition was organized in the halls of what is now the National Gallery of Modern Art. It was a particularly popular event, and several of the greatest artists of the time took part: suffice it to think that in that edition a masterpiece by Adolfo Wildt such as Pius XI was presented, but scrolling through the catalog of participants it is possible to find the names of Felice Carena, Ardengo Soffici, Pietro Gaudenzi and others, artists linked above all to traditional subjects but nevertheless in contact with the avant-garde of their time, so much so that a critic who reviewed the exhibition in Emporium, Renato Pacini, could lament that “for many the intentional deformation is still the ideal of inspiration, and this concept that can be more or less fallacious in the field of secular art is even deleterious in the field of sacred art [...]. If today the modern tendency is to move away from traditionalist forms for an art that is a character of our time, I do not believe that one can in the limit of sacred art solve the problem by futuristically painting saints and Madonnas, that is, by bringing to art value that which is fashionable and which perhaps can be art-not according to my concept-in a field absolutely different from that of images before which one must turn one’s soul to God.” Fortunately for Cagianelli, the exhibition’s jury, composed of six artists, namely Baccio Maria Bacci, Eugenio Baroni, Ferruccio Ferrazzi, Pietro Gaudenzi, Giovanni Guerrini and Attilio Selva, had broader views than Pacini’s and had no problem awarding a work, such as the Perugian sculptor’s Umbrian Nativity , that was open to multiple sources, ancient and contemporary.

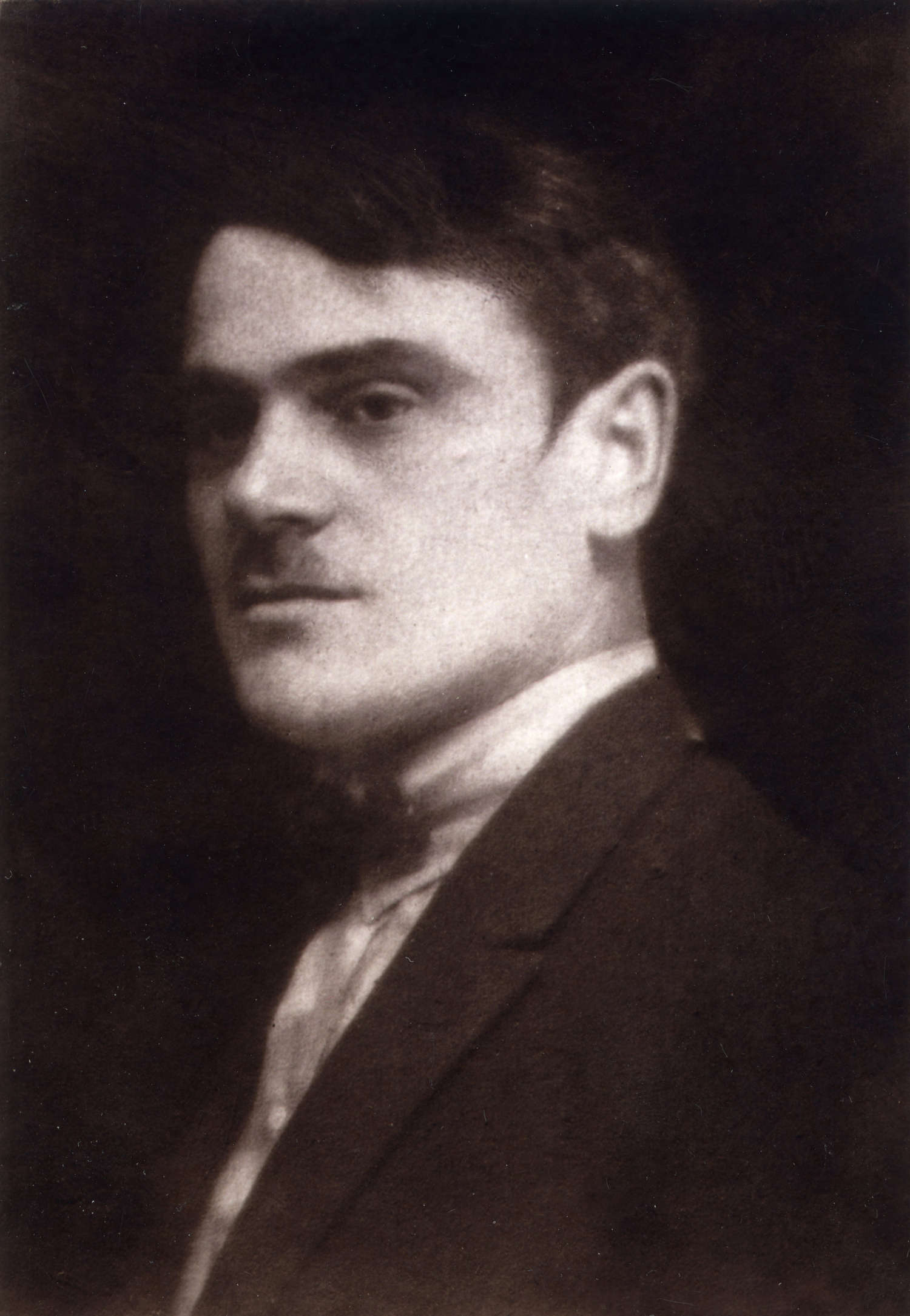

Cagianelli himself, after all, was a difficult artist to include in one category. Even his contemporaries were aware of this. This is how Gerardo Dottori spoke of him: “Futurist? Passatist? One cannot with precision classify him. If one attempted it one would have strange surprises. Certainly, as Marinetti said of him, he is a sculptor-born who possesses an unquestionable personality. He is varied, undisciplined, fickle in his art. He lets himself drift by the calm or impetuous current of his sensations. He has never bothered to seek his own way. He roams the fields, scampering about, intoxicated by his freedom.” A free artist, in short. Just as free is the Umbrian Nativity with which he presented himself at the ENAPI section of the 1934 Exhibition of Sacred Art: in fact, the organization had organized, within its section, three competitions intended for Italian craftsmanship, and reserved for organs of small churches, sacred book bindings and, precisely, nativity scenes. The idea behind the section organized by the body was to promote “new stylistic forms while respecting tradition and liturgical canons,” as stated in the pages of a magazine of the time, Modern Artist, which also attested to the success of thatexhibition, since it had been shown that the production of handcrafted nativity scenes was not the exclusive preserve of traditional centers such as Naples, Alto Adige or Lecce, but was spreading to ateliers throughout the country. Cagianelli was among the thirty participants in the exhibition, although only eight nativities were allowed to be exhibited in the rooms of the Royal Gallery: his own, and those of Vinzenz Peristi from Gardena, Arrigo Righini from Bologna, Dante Sernesi from Florence and Cavallari from Rome. Another magazine, Illustrazione Toscana e dell’Etruria, gives an account of a name that curiously does not appear in the report of Artista moderno, that of Maria Delago from Bolzano, a sculptor who was moreover very prolific.

Cagianelli presented herself at the exhibition with a nativity scene that looked to medieval statuary, especiallyRomanesque art, in which there was a strong interest at the time (and not only in the national sphere), but was’was also open to suggestions drawn from the avant-garde, according to a diversity of directions that also reflects the multiple interests of the Umbrian sculptor, capable of looking to futurism and cubism as well as to the historical-artistic tradition of his lands. The gaze turned toward medieval art was not, of course, the result of acquiescence to the wishes of regime critics, far from it: Francesca Cagianelli, a descendant of the artist and his scholar, has noted how the Nativity scene and, in general, the works the artist produced at the time were fully inserted in a European figurative context substantiated by a’accentuated primitivist vein that made possible experiences such as those of Émile-Antoine Bourdelle and Ivan Meštrović, to which one could add names such as those of Aristide Maillol, Jacob Epstein, or even the Jacques Lipchitz of the 1930s. In the characters of the nativity scene, originally made of white Furlo stone, a white-pink flake quarried in the Marche region, the Perugian sculptor, wrote Francesca Cagianelli in the monograph dedicated to Enrico, re-proposes, in a “frame that is perhaps less populist also by virtue of the materials chosen,” the “linguistic paradigm exemplified by the dramatic cadence of the various Stations of the Cross made between 1934 and 1936 for the church of Sant’Agata in Perugia, retraced on the wave of the language of the two-thirteenth century, never as on this occasion revived in relation to the spirituality of its religious content.”

One of the special features of Cagianelli’s Umbrian Nativity scene are the characters accompanying the Holy Family: these are the figurines in which the artist experimented the most, trying his hand at depicting the humble, the workers of the land that he could possibly study even from life in the Umbria of those years. Some characters, such as the shepherds approaching leaning on sticks or with loads of faggots on their shoulders, can be placed in the groove of contemporary expressionist experiences, and a character such as the Accordion Player from 1930 (the genesis of the Umbrian Nativity scene in fact dates to some time before 1934), Francesca Cagianelli notes, can be considered a “sort of reinterpretation [...] of Jean and Joel Martel’s terracotta players, albeit with the addition of a coloristic frisson and craftsmanship sensibility that reveal Umbrian spirituality.” On the other hand, the tendency to decompose forms (observed especially in the angels and certain shepherds with completely unnatural postures) is an obvious reflection of Cagianelli’s interests in the Cubist language, to which his art had long since approached. More traditional, on the other hand, are the depictions of the main characters, from the Holy Family to the Magi, which instead show closer ties to Romanesque statuary, revealing a certain debt to thirteenth-century wooden sculpture in Umbria.

Art historian Enzo Storelli, quoted in Francesca Cagianelli’s monograph, pointed out that the Nativity scene had some success: after the exhibition it was exhibited in Gubbio, casts of it were made in the workshop of ceramist Leo Grilli, and inspired by Enrico Cagianelli’s work in 1938 sculptor and ceramist Bruno Arzilli and painter Alessandro Bruschetti, who together with Gerardo Dottori could be considered two spearheads of Umbrian art at the time, made a similar nativity scene for the parish church of Monte Petrisco, near Perugia. “Like many sculptors of his time,” Storelli would have said, “[Cagianelli] gives much of himself, of his talent in works of small and medium size-in which he expresses a contained and contemplative archaism.” To see Enrico Cagianelli’s Nativity scene today, one can go to the Cagianelli Center for the 1900s in Pisa, where three plaster figures from 1929-1930 (the Accordion Player, the Wood Carrier , and the Shepherd) are on display, as well as some examples from the run of original casts.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.