Bernardo Strozzi's cook: a work of pilgrim ingenuity

His works will be “highly esteemed in every time and place” thanks to the “perfection in the use of brushes.” This is how Raffaele Soprani, in Lives de pittori scoltori et, architetteti genovesi (1674), opens the medallion dedicated to Bernardo Strozzi allowing, more than anything else, an understanding of why “Il Cappuccino,” author of the very famous Cuoca, is considered “Pittore tra i Genovesi di virtuosa fama.” Such an incipit might lead one to believe how simple it can be to analyze the pictorial corpus of an artist whose activity, due to his “pilgrim wits,” marked an extraordinary novelty in the Genoese scene, perhaps not fully understood. In fact, in the 1674 edition, the Genoese humanist indirectly tends to focus mainly on Strozzi’s youthful artistic training, pointing out how the artist’s rare and mind-bending pictorial language was certainly the outcome of the Cappuccino’s skill, which, however, would not have come so far without the indispensable “istradar [of someone] in the true rule of good drawing.” Such a premise might, therefore, be superfluous but, in fact, it fully enables us to understand how Strozzi’s innovative pictorial language, given its disruptive scope, was difficult to frame and, above all, to “justify” in a period when, at the turn of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the Cambiasque manner was established as the predominant culture.

Born in 1581 in Campo Ligure, Strozzi took his first steps at the workshop of Cesare Corte, among the most illustrious “followers” precisely of Luca Cambiaso, and then, during the very last years of the 16th century, continued his training under the aegis of Pietro Sorri. His frequentation of the Sienese master inevitably led him to reflect on the vivid Tuscan colors that were further deepened thanks to the presence of Aurelio Lomi, active in Genoa from 1597 to 1604.

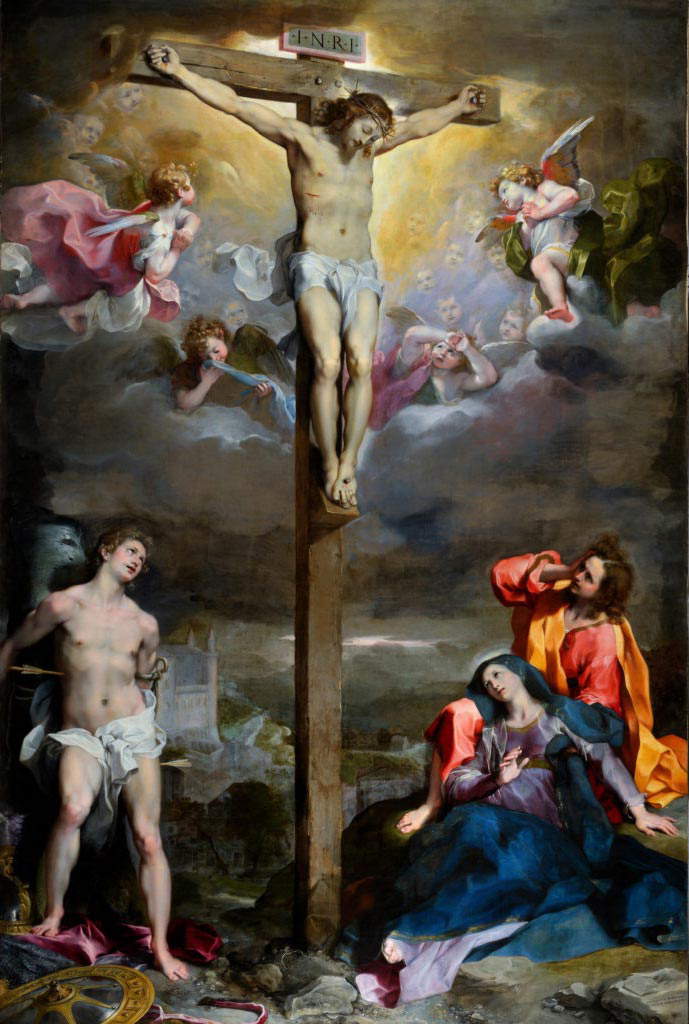

The late Mannerist influence, marked by Raphaelesque, Tuscan-urbinate chromatic range, was further accentuated in 1596 with the arrival in San Lorenzo of Federico Barocci’s admirable Crucifixion, placed in the Senarega Chapel. The latter’s appearance on the Genoese scene (an event that would deserve more critical attention) greatly enriched the artistic landscape of the Superb, allowing young local artists, such as Strozzi, to update themselves on the most innovative modi pingendi.

The Tuscan pictorial lemma, moreover, crept even further into the rigid meshes of the local artistic language thanks to the return to Genoa of Giovanni Battista Paggi, who, condemned to “perpetual banishment,” found first in Pisa and then in Florence a magnanimous hospitality thanks to which he entered the service of the Medici Court. Protected by Giovanni Carlo Doria and consort (Zenobia del Carretto), in 1590 Paggi returned to Genoa, a city to which he brought with him the fervent Medici cultural climate, linked yes to a new and lively pictorial far but, even more, to a new forma mentis that would allow painting to break away definitively from the mere corporative conception to achieve a definitive liberalization of the profession.

The dawn of the new century fueled this fervent cultural climate even more thanks to one of the absolute protagonists of European painting, Pieter Paul Rubens, who in 1605 painted, commissioned by Marcello Pallavicino, the extraordinary Circumcision for the high altar of the church of Saints Andrew and Ambrose, now more commonly known as the Gesù church. The scope and stylistic significance of the canvas must inevitably have attracted Strozzi who, like all painters in being, observed with particular attention the spatial but especially chromatic outcomes proposed by the Siegen master. It seems appropriate to point out, even if closer to the second decade of the seventeenth century, how the rich Genoese artistic proposal was further expanded in 1616 by Guido Reni’sAssumption and, five years later, Simon Vouet’s Crucifixion, also still at the Gesù Church. Reni’s more classicist language combined with Caravaggesque naturalism, professed by the French artist, completed a cultural framework by then consisting of the most up-to-date and revolutionary stylistic languages of the time.

In this articulated and rich artistic scenario, it seems most fundamental to open a necessary biographical aside concerning 1599, the year in which Strozzi, taking his vows, entered the convent of San Babila, a Franciscan institution at which he remained until 1608-1609 and which allows us to understand why in the chronicles he is remembered under the pseudonym of “Il Cappuccino” or the “Genoese Priest.”

In spite of the inevitable restrictions due to convent life, because of the skillful mastery he achieved in the use of the brush, Bernardo could not limit himself exclusively to a careful analysis of local proposals but, in the first decade of the century, had to frequent artistic centers such as Rome (1608?) and especially Milan, which were fundamental for fully grasping and learning a common taste that by then was increasingly moving away from Mannerist mannerism.

And it is certainly no coincidence that the “Reverend Bernardo Strozzi [of] 28 years of age” appears in the States of the souls of Milan in 1610. In that year, in fact, he appears as a tutor to the nobleman Andrea Manrique de Lara y Mendoza, son of Giorgio and Giustina Borromeo, a family linked to the better-known Cardinal Federico, commissioner of the famous Canestra di frutta.

Attention to the rendering of the natural datum, moreover, became an even more familiar aspect thanks to the figures of Giulio Cesare Procaccini, Giovanni Battista Crespi known as “Il Cerano” and Pier Francesco Mazzucchelli known as "Il Morazzone.“ The importance and excellence of the three painters is well attested by an epistolary correspondence between the literati Borsieri and Marino in the course of which the former specifies how the gift of a canvas by Cerano addressed precisely to his friend resulted ”ventura di sommo principe, che premio di privato." The language of the three Lombards, in fact, fascinated, and not a little, a refined and up-to-date patron such as Giovanni Carlo Doria who, during his visits to the city of Milan accompanied by Luciano Borzone, acquired numerous works on naturalistic themes. The fruit of such acquisitions conveyed to the nobleman’s residence located in vico del Gelsomino, a residence that also became the seat of the Accademia del nudo, established by Giovanni Battista Paggi and sponsored by Giovanni Carlo himself. Thanks to this institution the leading artists of the time, including our own Bernardo, were able to further their study of this fascinating genre. Thus, knowledge of the naturalism professed by the Lombards and Caravaggio, combined with the vivid colors of the Tuscans and Rubens, constituted a solid cultural substrate for Strozzi.

Central, then, in the Capuchin’s artistic formation turns out to be the figure of Giovanni Carlo (famous for his Equestrian Portrait “vivified” by Rubens) so much so as to be, according to Boccardo’s suggestion, the gentleman to whom we owe the commission of perhaps among the most iconic works of the painter’s production: The Cook.

The canvas can be generically dated around the early 1620s (ca. 1625); this uncertain chronological framing, relative to much of the Strozzesco corpus, can be ascribed not only to a biographical narrative particularly attentive to lively religious-judicial events, but above all to a skilful workshop organization that led Bernardo to have numerous helpers focused on completing the works baked by the master and on a constant serial reproduction of particularly fortunate subjects. The workshop inventory of 1644 (the year of the artist’s death) gives an account, in fact, of “paintings by the hand of Signor Don Bernardo,” “sketches,” and “several copies taken from the paintings of Monsignor aforesaid.” Such “incomplete” authorship certainly does not concern the work under consideration, which, for its refined, powerful and textured composition fully reflects the acknowledged “perfettione nell’uso de pennelli” achieved by the Genoese painter.

Known as La cuoca (The Cook), if one takes into consideration the customs and traditions of the time, which saw the role of cook reserved mainly for the male rank, the effigy should perhaps more properly be traced to a woman of more “humble” employment, perhaps a servant, intent on plucking a goose. What is certain is that, regardless of the task performed, the refined female figure is within an “aristocratic” kitchen, as the silver tinplate in the foreground and the rich variety of game, worthy of a true royal banquet, well testify.

Regardless of the timely identification of the cook’s task, what is most striking is the skill with which Strozzi delineates the face of the maiden, whose gaze, sketched with tangible brushstrokes, cannot help but captivate the viewer’s attention. From a stylistic point of view, moreover, Strozzi’s debt to Barocci appears particularly evident, from whom he takes the candid rendering of female faces, emphasized through the slight redness of the cheeks.

The Tuscan matrix (afferent to a more generic Umbrian-Tuscan Mannerism) is denoted, moreover, in the chromatics of the entire composition which, despite the secluded monotonous interior of the kitchen, do not fall into indistinguishable and gloomy chromatic “spots” but rather, through a crisp palette, seek to faithfully render each and every chiaroscuro contrast.

Bernardo

Bernardo Bernardo Strozzi, The

Bernardo Strozzi, The Bernardo Strozzi,

Bernardo Strozzi, Bernardo Strozzi, The

Bernardo Strozzi, The Bernardo Strozzi, The

Bernardo Strozzi, TheBut the opportunity to “see the works of the best masters” in the Genoese land (and beyond) led Cappuccino to reflect inevitably also on Rubensian novelties rubensiane, thanks to which the Tuscan tints merged with that chromatic “earthiness” familiar to the Flemish master, centered on reddish-brown tones, clearly evident in the glittering fire enveloping the boiling cauldron. Masterful moreover is the steam made tangible by the contrast with the illuminated wall behind in the background.

The chromatics, therefore, play a preponderant part in the fascination aroused by this work, which, however, increases even more its intrinsic beauty thanks to the extraordinary still life pieces that punctuate every single portion of the canvas. The Lombard lesson, for the reasons previously stated, appears definitively understood and made explicit by a rendering of the natural datum at the limits of lenticularity. The precision with which aspects of the sensible world are rendered are also to be traced in that Flemish “colony” which during the early seventeenth century found itself in instance in Genoa and of which Jan Roos and Giacomo Legi represent a useful comparison.

The refined silver tinwork, the ruffled drapery of the cook, her refined headdress, intent on “containing” the disheveled hair, constitute elements of absolute adherence to the world us surrounding. But what perhaps most of all explicates the wisdom achieved by Strozzi in blending all the assimilated artistic components can be well traced in the work’s indirect protagonist, thegoose, whose “natural” plumage, rendered through the “pastiness” of the chromatic material, is investigated in every single nuance through the use of particularly vivid and vibrant hues. Striking, moreover, appears the skill with which Strozzi succeeds in rendering a decidedly intense action, such as “plucking,” in a delicate and slight manner: the cook’s right hand, intent on removing the first feather, fully manifests such sensitivity, allowing even more to remark on a total understanding of adherence to true-Flemish and Caravaggesque naturalism.

In addition, although mere hypothesis, it seems interesting to point out a key provided by critics that The Cook can be read as an allegorical representation of the four natural elements, found in the birds, the silvery tinplate, the cook and fire, which can be associated with air, water, earth and fire, respectively.

In conclusion, it can be stated how the naturamortist genre (despite Strozzi’s predilection for religious narrative and portraiture) appears to be remarkably investigated and proposed by Cappuccino even in canvases widely distant in subject matter addressed, as evidenced by the Tobias cures his father’s blindness in New York. While not representing conceptually refined and elevated painting, his adherence to the real enjoyed no small amount of success in the Genoese milieu, a success that Strozzi tried to “transfer” to the lagoon land, where he repaired in 1635 following a “proud storm of controversy.”

And it can hardly be a coincidence that, in an attempt to reintroduce a not particularly popular genre in the Lagoon, the inventories of the Venetian workshop established by Strozzi in Santa Fosca include a second “Cuoga with several chickens,” listed as being by the hand of “soddetto signor don Bernardo.” The copy, now housed in the National Gallery of Scotland in Edinburgh, appears to be a complete mirror image (slightly smaller in size due to obvious curtailment) and, therefore, could be derived from a cartoon taken from the Genoese prototype, brought by the artist himself to enrich his Venetian workshop following his escape from the Superb. The hypothesis resulting from the transposition of an already existing Genoese cartoon is further supported by infrared investigations, thanks to which it was possible to ascertain that the “Venetian cook” does not show, unlike its Genoese “sister,” obvious signs of repentance in preparation, the outcome of a sped and certain graphic elaboration.

The Scottish version, unlike the canvas examined so far, also differs in some aspects such as: the absence of the cauldron, the replacement of the silver tinner with a copper one, and the presence of a decidedly more nourished game than the more frugal Genoese canteen.

Again thanks to the IR images, however, it was possible to see that in the Edinburgh cloth the only striking repentance concerns the silver tinner, which, infrared analysis showed how it had originally been maintained by Bernardo who, however, for reasons unknown to this day, decided to replace it with a more humble copper vessel.

Many keys appear, therefore, through which it is possible to read a work such as The Cook, which, the result of a mixture of influences masterfully assimilated and re-proposed by Strozzi through a completely unique, new and personal stylistic figure, can be considered without any doubt the most iconic and intriguing pictorial testimony of the Genoese cultural panorama as well as one of the most fascinating and well-known at the European level.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.