Benvenuto Cellini's Perseus. The story of a masterpiece of Mannerism.

There is a particular anecdote that is often told around Benvenuto Cellini ’s Perseus with the Head of Medusa (Florence, 1500 - 1571), the Florentine sculptor’s great bronze masterpiece, the symbolic monument of Mannerism, more than five meters high, that towers under the Loggia dei Lanzi in Piazza della Signoria in Florence. It was commissioned from him in 1545 by Duke Cosimo I de’ Medici, and took nine years to complete. The anecdote is recounted by Cellini himself in his autobiography, the Vita di Benvenuto di Maestro Giovanni Cellini Fiorentino written for him: the artist had begun to prepare the bronze casting in his furnace, but because of too much fire the alloy had become excessively dense, and it needed to be made more fluid by adding tin. “I had taken,” Cellini writes in his Life, “all my plates and bowls and rounds of tin, which numbered about a hundred, and one by one I placed them before my channels, and part of them I had thrown drento the furnace; So that when each one saw that my bronze was well made liquid, and that my form was filled, they all animatedly and gladly helped and obeyed me; and I here and there commanded, helped and said: ’O God, who by Your immense virtues You raised from the dead, and glorious You ascended to heaven!’”. In essence, to lower the density level of the league.... Cellini had lost out on his crockery. On the occasion of a conference on Cellini held in 1971, for the fourth centenary of the artist’s death, restorer Bruno Bearzi had the alloy of which the figure of Perseus was composed analyzed and noted that, unlike that of the head of Medusa (consisting of 90 percent copper and 10 percent tin), that of the hero bore a curious composition: 95.5 percent copper, 2.5 percent tin, 1 percent lead and 1 percent zinc. “And with the plates,” Bearzi concluded, “the presence of lead and zinc is explained.”

The making of this challenging work was, indeed, quite painful. In 1545 Cellini had just returned from France, where he had delivered to King Francis I the celebrated Saliera, which today figures among the most admired pieces in the collection of the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. Cosimo I commissioned him to make a bronze statue to flank Donatello’s Judith for the Loggia dei Lanzi, and to make his work easier he also gave him a foundry in what is now Via della Pergola. The artist, as we learn from the Vita, immediately set to work to make an initial model in yellow wax, as was the practice (and in his autobiography Cellini does not fail to say that the model “well was made with grandissimo istudio and art”). However, problems with the excellent patron immediately began to become apparent: Cosimo I was often absent, delayed, and troubled the artist over payments so much so that he is even described as a gentleman who behaved more like a merchant than a duke, leading Cellini to the point of regretting not having fixed all the conditions of the work on a contract. What’s more, the artist had constant disagreements, when not quarrels, with the duke’s servants (he often refers to them as “beasts”), and also with one of the most great artists of the time, Baccio Bandinelli, his bitter rival (Cellini, who calls him “Buaccio” mispronouncing his name, complained that Bandinelli was taking away his best workers on the square and in doing so delaying the delivery of the work, so much so that he went so far as to expose the problem to Cosimo himself: “I complained to the Duke of the great boredom that this beast was giving me.”). But that’s not all: the work was saddened by the death of his brother-in-law, his sister’s husband, with the consequence that the artist had to take charge of his family.

Benvenuto Cellini was still determined to continue his work, however, but the situation threatened to precipitate as a result of blackmail the artist was subjected to by the mother of one of his apprentices, 18-year-old Bernardino Manellini, who was wanted on suspicion of sodomy: the mother asked Cellini to put him up in her house, and to the artist’s refusal, the woman replied by saying that he was also under suspicion of having “sinned” with Bernardino, but that if he gave him a hundred scudi to bribe the authorities, everything would go smoothly. Cellini responded in his own way (insulting the woman and threatening her with a dagger), but in order to be safe he left Florence and moved to Venice for some time, taking Bernardino with him. That was in 1548: the artist returned to Florence after a few months, and in the summer of that year he finally cast the head of Medusa, the first part of the monument to be completed. Work languished, however, because Cellini had few collaborators, and because his enemies were stonewalling by spreading bad rumors about his ability to complete such a demanding work (and Cosimo I himself, according to the account in the Life, began to have doubts): the artist, however, at the cost of losing his health (he was in fact ill and bedridden perhaps from metal fumes), managed to complete the work, and between 1549 and 1550 the group was finally completed. It then took another period of time, between three and four years, for renetting and the finishing and decorations. Eventually, on April 27, 1554, the statue was uncovered under the Loggia dei Lanzi, where it still stands today. To the great satisfaction of Cellini, who received the praise of the duke and the appreciation of the Florentines: “Immediately, that e’ nonnera still clear the day, there was gathered there such an infinite quantity of people, that e’ saria impossible to say it, ettutti a una voce did gara a chi meglio dire ne.” Less satisfying, however, was the economic gratification: Cellini, for his work, obtained only 3,300 scudi, compared to the 10,000 he had hoped to receive. The work was a success, but the history between the artist and the duke did not favor the continuation of the collaboration: from then on, in fact, Cellini would no longer work for Cosimo I.

Cellini’s large sculptural group depicts the mythological hero Perseus, son of Zeus and Danae, slayer of Medusa, one of the three Gorgons, who petrified anyone who looked at her with her eyes: Perseus was able to kill her by looking at the monstrous woman in the reflection of the shield. The work was cast in four pieces, then assembled: the head of Medusa, the body of Medusa, that of Perseus, and the sword (the original of Perseus’s weapon, replaced in 1945 by a copy as it had deteriorated due to weathering, is kept at the Bargello National Museum, where the original marble base with the bronze statues is also located, as well as the two surviving models of the sculpture, one in bronze and one in wax). Precisely because of the monument’s size, and the choice to cast it in such a small number of pieces, it was a technical challenge to the limits, an operation that required the use of a large amount of metal (the work weighs a total of 24 quintals). Instead, the choice of subject had an eminently political significance. The Greek hero, “a male figure who had made a gesture similar to Judith by chopping off Medusa’s head,” wrote art historian Francesca Petrucci, “was supposed to represent the response to the past republic by showing the triumph of the ducal empire. Already in the choice of the rare subject Cosimo was inspired by Etruscan bronzes, which he researched and collected to recall the mythical origins of Florence and the ancient rulers of Tuscany, victors over the Romans under the leadership of King Porsenna, an absolute monarch who seemed to legitimize the new dynastic course proposed by himself.”

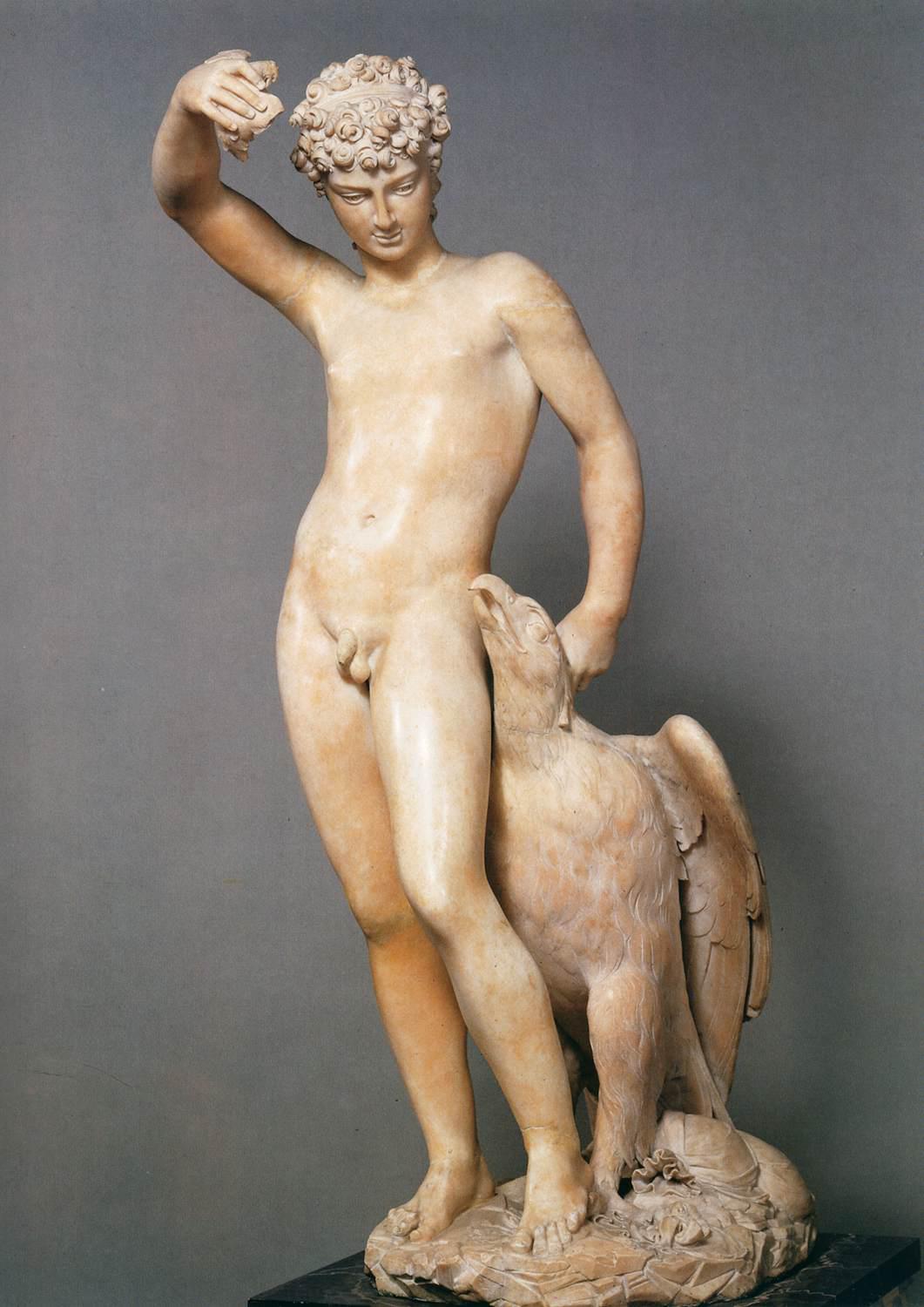

The hero is depicted as a young man with an adolescent face (apparently the model was Bernardino Manellini himself), in contrast (the right leg is straight and on it the figure unloads his weight, while the left is at rest, with the knee advanced and the foot raised), while with his left arm he lifts the head of Medusa to show it (from the severed head and neck gush streams of blood: no one before Cellini in sculpture had dared so much), with his right he still holds the sword that decapitated her, and rests his feet on her body in victory. The pose recalls that of Michelangelo’s David, although her back is slightly turned to the side, following that famous serpentine line that was typical of the taste of the time. The work is studied from life, but conceived according to a well-thought-out pose, which also appears in another work Cellini completed at that time, the Ganymede, which was actually a restoration of a Roman torso received in 1548 from Cosimo I (the artist added the base, feet, eagle, arms and head to it: it was delivered finished in 1550). Perseus is completely nude: he wears only the winged footwear that allowed him to move quickly, the bag that would have contained Medusa’s severed head (on the shoulder strap, moreover, the artist has left, very evidently, his signature: a clear Michelangelo reference, since Buonarroti had signed the Vatican Pietà in the same way, writing his name on the Virgin’s shoulder band), and the helmet of Hades, which according to the myth made him invisible. Observing the helmet from below, by the way, a human face will be easily distinguishable: it has been assumed that Cellini exploited this expedient, with a typically Mannerist artifice, to include his own self-portrait in his best-known and most difficult sculpture. More likely, if anything, is that the artist wanted to create a parade helmet with a mask on the nape of the neck, along the lines of the bizarre coeval creations of the Milanese armor-maker Giovanni Paolo Negroli (Milan, 1513 - 1569), from whose forge came out “heroic armor” in the most disparate shapes, which did not lack helmets with animal or anthropomorphic forms. Moreover, Negroli had also worked for the Medici: it was, in essence, an object in line with the taste of the courts of the time, and the Florentine court was no less.

The elongated proportions of the figure respond to the need for a view from below: Benvenuto Cellini’s Perseus was in fact, at that date, the only work expressly made for that location, where it has always remained, except for a brief period between 1996 and 2000 when it was moved to be restored. The titanism of the gigantic figure (the statue alone is more than three meters tall) has its most direct antecedent in Michelangelo, Benvenuto Cellini’s main point of reference (the David was nearby, after all, but another model was undoubtedly Donatello’s bronze David ): the enterprising and determined goldsmith and sculptor saw in this enterprise a challenge in all respects, and the hero’s proportions also became an allusion to his virtue triumphing over adverse chance. Cellini, Petrucci writes again, proposed himself as a “model of the greatness of genius and, ultimately, as the last heir of the craftsmanship method in use in Florentine workshops before Cosimo I activated the iron organization of the arts at the service of political power with the creation of the grand ducal workshops.” One could then also read into it a polemic with regard to the eternal enemy Baccio Bandinelli: a few years earlier, a very short distance away, in Piazza della Signoria, his group, theHercules and Cacus, had been discovered, much criticized even by his contemporaries (and of course by Cellini himself) because of its overly charged and excessive interpretation of Michelangelo’s titanism, with bodies of massive proportions and bulging muscles in strong evidence, and tormented faces. Cellini opposes to his rival’s figures a figure that is indeed grandiose but at the same time also capable of retaining a certain grace, especially in the face.

Of the Perseus, as anticipated, we preserve two models, one in wax and one in bronze, a rather rare fact for Renaissance sculpture. They are, moreover, the only two records of the work’s working stages, since no drawings or sketches have come down to us. We do not know how they came down to us: there is no mention of them in the inventories of Benvenuto Cellini’s possessions, reasoning that it is likely that the artist had given them to someone close to him. They reappeared in 1826: they were in the possession of a Florentine painter and art dealer, Fedele Acciai, who proposed them to the Uffizi for purchase: the institution accepted and the two models became part of the museum’s collections, which then in 1888 gave them to the Bargello National Museum. The wax model presents an already rather advanced idea of the work: “Cellini,” wrote scholar Maria Grazia Vaccari, “aims at the rendering of the overall effect, so as to put the client in a position to be able to evaluate the project. That is why he does not dwell on defining all the details, limiting himself to suggesting some solutions, modeling, for example, only one of the shoes. The figure appears slender and slender, with an underdeveloped musculature, but the tension of the victorious gesture of the left arm lifting the severed head and the right arm still holding the weapon is already fully expressed.” With the bronze model, we come even closer to the finished work, since here the details are much more defined, and the sketch shows, Vaccari again writes, “how the artist is still linked to the world of goldsmithing in his search for an elegant rhythm and formal refinement.” Comparison with the models shows how the monumental work acquires decidedly more robust proportions, in line with the allegorical bearing of the subject, but perhaps also for reasons of statics. Not only that: the face of Perseus also changes, losing the naturalness it had in the model and acquiring a greater ideal beauty, suitable for a Greek hero.

Also of particular finesse is the plinth, the original of which, as mentioned, is kept at the Bargello National Museum, for reasons related to the preservation of the monument. On the four faces the artist has carved as many niches within which he has placed four bronze statues of characters related to the Perseus myth: the hero’s father, Jupiter, his mother Danae, depicted together with Perseus as a child, and finally Mercury and Minerva (the former gave him the weapon to decapitate Medusa, the latter had given him the shield to observe the reflected image of the Gorgon). Each of the characters is accompanied by an inscription in Latin that identifies him, according to the program developed by the scholar Benedetto Varchi. Under Jupiter appears the inscription “Te fili, si quis laeserit, ulter ero” (“Son, if anyone offends you, I will avenge you”), under Danae “Tuta Iove ac tanto pignore laeta fugor” (“Protected by Jupiter and glad for such a great commitment, I go into exile.” refers to the fact that the princess had to live far from her father Acrisius to avoid being murdered by him along with his son, since according to a prophecy Acrisius would be killed by a nephew), under Mercury “Fr[atr]is ut arma geras, nudus ad astra volo” (“I fly naked to the sky so that you may bear your brother’s weapons”) and finally under Minerva “Quo vincas, clypeum do tibi, casta soror” (“I, your chaste sister, give you this shield that you may win”).

These characters are not only inserted to provide a narrative framework for the monument: they also have an allegorical function, since they rise as symbols of the forces that determine the destiny of Medici Florence in general and Cosimo I in particular (which, as we have seen, is to triumph over enemies). Indeed, it will be necessary to add that, on the sides of the base, carved in marble, we see some goat heads: capricorn was probably his ascendant zodiac sign and was certainly linked to the Emperor Augustus, so much so that Cosimo decided to adopt it as his personal feat. Also preserved at the Bargello is the bronze relief that stood beneath the marble plinth (now replaced by a replica), depicting the episode of the liberation of Andromeda from the sea monster by Perseus: again, this was a work of clear political significance, similar to that of the monument. A statement of triumph over the republic (the monster), a warning to anyone who dared to challenge Medici power. Decidedly peculiar is the decoration of the base, with the festoons of flowers and fruit, the grotesque masks, and the caryatids at the corners taking on the likeness of the Diana of Ephesus, with her feet resting on the water, symbolizing the impossible (like that challenged by Perseus with his heroic feat): iconographic motifs also probably suggested by Benedetto Varchi (perhaps an allusion to the fruits of good government, perhaps an image of the idea of nature according to Varchi), were above all ornaments without precedent in Florence, and which derived, if anything, from France, where Cellini had stayed before returning to his native city. The most direct precedent, John Pope-Hennessy noted, was the stucco work executed by Francesco Primaticcio at the Palace of Fontainebleau for King Francis I.

Benvenuto Cellini, Model for Perseus with the

Benvenuto Cellini, Model for Perseus with the

The most important restoration that the Perseus underwent was the one that began in 1996: at that time an attempt was made, for the first time in history, to move the statue from the Loggia dei Lanzi to take it to the Uffizi, where the room had been prepared to conduct the intervention, which had become necessary in order to thoroughly assess the state of preservation of Benvenuto Cellini’s masterpiece and to remedy its problems. The transport succeeded without problems: the Perseus was moved in a large steel cage, designed for the occasion by engineer Antonio Raffagli, who had had to take into account the fragility of the work and its weight. Centuries of weathering had altered the surface of the bronze, so much so that, after the work’s arrival at the restoration laboratory, the first year of the intervention and much of 1998 were spent under the banner of diagnostic investigations, carried out by theOpificio delle Pietre Dure in Florence and theIstituto Centrale per il Restauro in Rome (the former dealt with the analysis of the alterations, while the latter investigated the surfaces and the alloy): the results were used to guide the laboratory of Giovanni and Lorenzo Morigi, who handled the material operations instead. Thus, an initial washing of the work with water spray was carried out to dissolve the accumulations deposited on the surface of the bronze: the subsequent cleaning served to remove deposits and residues that had covered the bronze, and had to be conducted with different methods (some deposits, the more tenacious ones, were removed with scalpel and ultrasonic scaler). Singular was the treatment that Giovanni and Lorenzo Morigi reserved for the Perseus in order to identify areas of active corrosion, those that would therefore begin to manifest problems even at the end of the work, if not fixed. “The sculptural group,” the two restorers recounted, “was enclosed in a large sealed polyethylene bag and water vapor was insufflated inside for 96 hours. The high percentage of relative humidity accelerated the formation of green copper oxychloride powder expulsions from the active corrosion craters, allowing the exact location of the foci to be identified. Once the wet chamber was removed, we found that there were a large number of active craters, mostly of modest size but, especially among the hair, a substantial group of large and particularly virulent craters.” The areas of corrosion were fixed with protectants to prevent further alteration, and finally the restoration was concluded with the application of two coats of a clear outdoor acrylic and three coats of a high softening temperature microcrystalline wax to further protect the surface.

At the end of the work it was realized that the base was too delicate to allow it to return to Piazza della Signoria: so it was arranged to be transferred to the Bargello National Museum, and a faithful copy was made for the Loggia dei Lanzi. It initially seemed that the sculptural group would also have to be admitted to the museum because of the critical state of its preservation: however, in the end the predictions of the eve were overturned by the evaluations of the technicians who deemed the Perseus capable of returning to the square without particular danger, provided it underwent regular maintenance. The Perseus finally returned to its place on June 23, 2000, with a new ceremony anticipated by a theatrical prologue performed by Flavio Bucci and Alessandro Haber. Since then Benvenuto Cellini’s Perseus has continued to show itself to the eyes of millions of people who every day, between Palazzo Vecchio and the Uffizi, lift their gaze to admire that “disaster turned into success,” as Alessandro Cecchi effectively called it, the best-known work by one of the most extraordinary figures of the 16th century, which has become one of the symbols of Florence and Italian art.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.