If one wished to list the capitals of the Baroque, perhaps the collective imagination would hardly grant the town of Pontremoli one of the first places on the list: yet, between the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the important center of Lunigiana witnessed a lively flourishing of the arts, with a concentration that can be compared, even taking into account the size of the town, to that of the great Italian cities. This artistic and cultural flourishing was due to a favorable economic situation that guaranteed the town’s prosperity for decades. One can therefore speak of "Baroque Pontremoli" given the spread that the Baroque experienced in the town, so much so that today, tours are regularly organized to discover this soul of Pontremoli, such as those of Sigeric. Baroque Pontremoli has a specific conventional date of birth: September 28, 1650, the day Florentine senator Alessandro Vettori arrived in Pontremoli to take possession of the town on behalf of the Grand Duke of Tuscany, Ferdinand II, who had purchased it from the King of Spain, Philip IV, for the considerable sum of 500,000 scudi. The sovereign had decided not to grant his ratification to the agreement by which, three years earlier, the Spanish governor of Milan ceded Pontremoli to the Republic of Genoa, with the result that the complex negotiations were broken off and Florence, given its attractive offer (more than twice the sum Genoa would have paid), succeeded in obtaining the significant trading junction of Pontremoli, located on the road that connected the Tuscan territories to the Duchy of Parma and Piacenza and to Milan. For the Pontremolese, already vocated to mercantile activities, it meant considerably expanding their interests, having access to the rich markets of Florence and Livorno and the possibility of serving as an indispensable axis to connect them with northern Italy. Add to this the considerable financial and fiscal privileges that Pontremoli was able to take advantage of under the Grand Duchy of Tuscany: the substantial fiscal autonomy the town enjoyed represented a further factor in its development.

Thus it was that between the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries arose in Pontremoli, as the scholar Vasco Bianchi has written, “a new patriciate of mercantile and industrial origin that flanked the old noble class and sometimes replaced it. In other cities, the rich bourgeoisie tied their economic fortunes to the land; the nobles and wealthy bourgeoisie of Pontremoli, while not disdaining the purchase of land, engaged instead in industrial and commercial activities, taking advantage of the favorable conjuncture, in which they had come to find themselves as intermediaries between the port of Livorno and the great cities of northern Italy.” A new rising social class that strongly nurtured the desire to show off the prestige it had acquired: the years between the two centuries thus saw in Pontremoli a strong building renewal, promoted by the families that had made their fortunes with their activities expanding also in Tuscany and Emilia (Dosi, Bocconi, Pavesi, Damiani, Bertolini, Ferdani, Negri, Petrucci, Pizzati, Ricci, Venturini: these are the recurring names in the events of Baroque Pontremoli), and which led the town center to assume the physiognomy that even today can be admired by walking around its elegant streets.

Pontremoli was a town that had basically not undergone any transformations during the Renaissance, which is why the interventions of the seventeenth-century town went to insist directly on a medieval village, which remained almost intact until the seventeenth century. In these years the face of the city changed dramatically: “a series of Baroque scenic wings,” wrote scholar Isa Trivelloni Manganelli, “gives the sensation to those who walk through the space, dimensionally unchanged, of being at the center of an ever-changing perspective. Elegant portals and windows framed with great display of worked stone (the sandstone of the rivers that lap the city), delightful wrought-iron balconies with expert craftsmanship, street entrances that hint at porticoed courtyards, with a succession of arches even in the elevation and, often, gardens and loggias adorned with statues.” A facies that the city would later maintain over the centuries, and this is the one with which it still presents itself today, with few substantial changes, to the eyes of the traveler who comes to the historic center. The Capuchin friar Bernardino Campi, visiting the city at the beginning of the 18th century, would have had occasion to describe its qualities: “Not a little praised is Pontremoli for the many palaces and comfortable houses of the inhabitants, for the most part in our days restored to and reduced to a more modern form, nobly adorned and adorned with remarkable furnishings, as s’è più volte veduto nell’alloggio di diversi qualificati personaggi e gran principi.”

Campi then went on to look in detail at some of the palaces, starting with what is still today the most representative and emblematic example of Pontremoli Baroque, Villa Dosi Delfini, an unmissable stop on any tour to discover Baroque in the city. Built in the locality of Chiosi, on the outskirts of Pontremoli’s historic center, the sumptuous mansion dates back to the last years of the 17th century: it was built by the brothers Carlo and Francesco Dosi (their busts can be admired on the villa’s façade along with the family coat of arms, consisting of a stork and a tower), wealthy merchants who had greatly expanded the family’s fortunes precisely as a result of Pontremoli’s passage to the Grand Duchy of Tuscany. The date affixed to the facade indicates 1700 as the date to which the villa dates: we actually know that the construction of the building was already finished in 1693, the year in which Villa Dosi Delfini is referred to as a “palace with garden” and the purchase of works of art to decorate it is attested. One of the many special features of the villa lies in the fact that the Dosi Delfini family still owns the property (it is therefore a private residence, but open for visits). Consequently, to visit Villa Dosi Delfini is to admire not only the best-preserved example of Pontremolese Baroque, but also to experience an aristocratic residence that, apart from a thirty-year interlude in the Napoleonic era when the villa was abandoned, has always been inhabited by the same family, which has carefully preserved it.

The visit begins from the large two-level hall, along which runs a wrought-iron gallery, and which surprises the visitor with its wonderful decorations capable of offering an important example of the main genre in which Pontremolese Baroque is substantiated: decorative painting on quadratures. Quadratures are sumptuous painted scenographic apparatuses that offer the visitor the impression that space expands beyond its physical limits: all rooms, such as the salon of Villa Dosi Delfini, are filled with paintings that occupy the quadratures, elements created by specialized painters who imitated architecture or broke through space perspective. The frescoes in Villa Dosi Delfini were most likely executed between 1697 and 1700 by Francesco Natali (Casalmaggiore, 1669 - Pontremoli, 1735) and Alessandro Gherardini (Florence, 1655 - Livorno, 1723): the former was in charge of the quadratures, while the latter (who, as will be seen below, had already worked for the Dosi: for Natali, on the other hand, it was his first assignment on behalf of the family) painted the frescoed scenes within the settings drawn by his colleague. Thus we can admire Natali’s extraordinary faux-architectures in which Gherardini’s figures take their place: the enthroned Virgin, the three Fates, a then-crowned poet, a life-size woman. The hall’s uniqueness, however, lies precisely in Natali’s intervention: although still less famous than his Florentine colleague, and even less experienced at the time (the commission at Villa Dosi was his first major work engagement and independent of his brother Giuseppe, also a quadraturista), Francesco Natali played a leading role in bringing the paintings in the salon into dialogue with the outdoor spaces, since everything is calibrated on a strict balance that also extends to the villa’s garden, the driveway, the splendid Chiosi bridge and the chapel that stands near the bridge, also designed by Natali. The space of the salon is punctuated by a large number of Corinthian twisted columns, closed by a mock balustrade imitating marble, with decorations studied in the most minute detail: an inspiration, Natali’s, that is also evident in the other rooms of the main floor of Villa Dosi Delfini, where indeed according to some the young quadraturist, free in some rooms from his collaboration with Gherardini, had a chance to express himself at his best. “The barrel ceilings,” Luciano Bertocchi has written, “stretch out, prolonged by columns and pillars, to open into small domes full of light that become a limit to the gaze and at the same time sources of a bursting luminosity.”

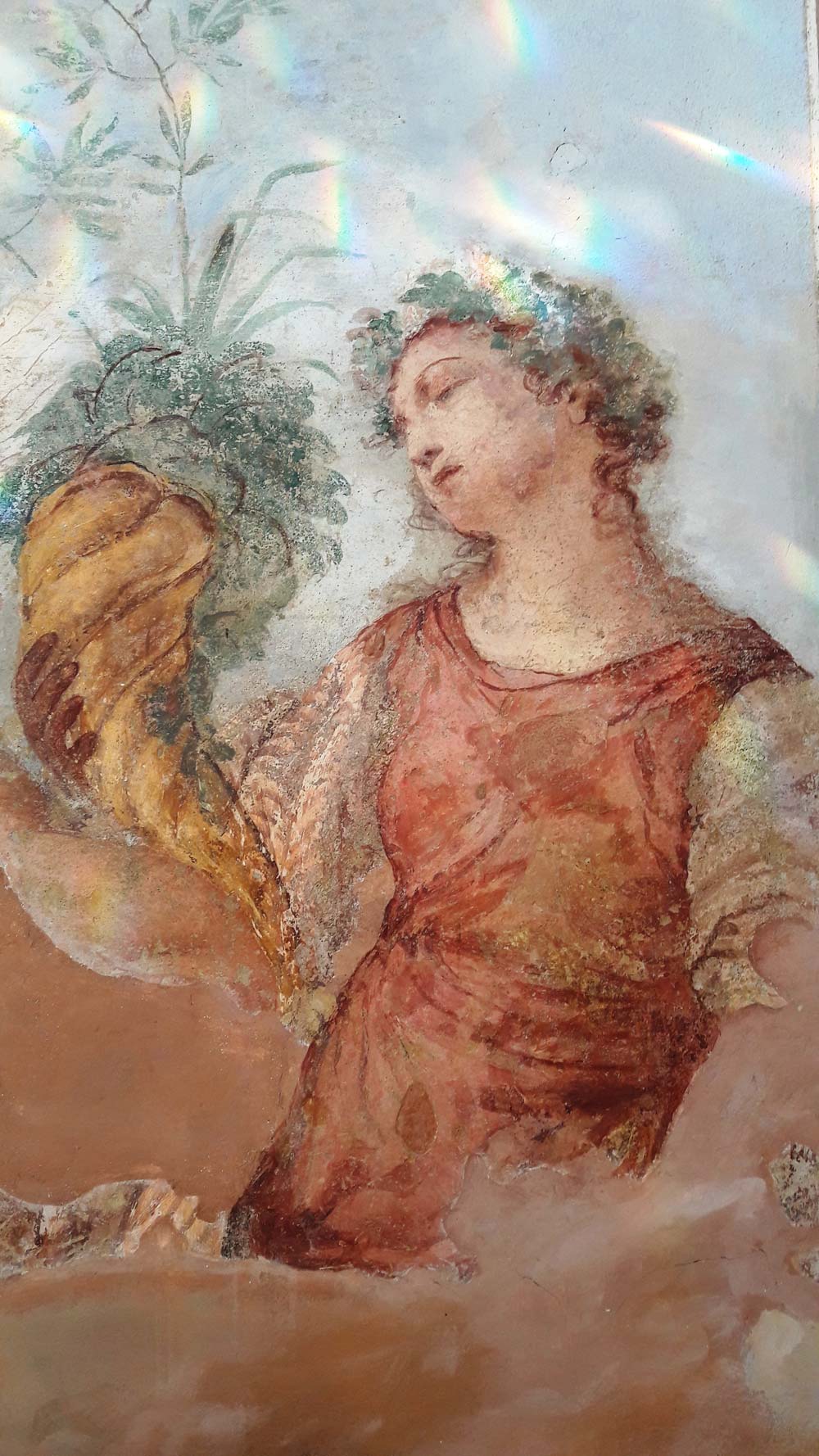

It has been said that the Villa Dosi Delfini commission was not Gherardini’s first engagement for the Dosi family: in fact, a letter from Carlo Dosi dated October 1689 documents the painting of a canvas depicting the Miracle of St. Nicholas that the Florentine artist executed for the family’s city palace, Palazzo Dosi, known today as Palazzo Dosi Magnavacca since it was purchased by the Magnavacas in 1931. The building we see today is the result of the transformations the complex underwent between 1742 and 1750, when architect Giovanni Battista Natali (Pontremoli, 1698 - Piacenza, 1768), Francesco’s son, was commissioned to fully renovate the palace. Natali was also responsible for the quadratures of the piano nobile: the most important work is certainly the decoration of the Salone where the artist is “veiledly neoclassical,” writes Luciano Bertocchi, “seeking no longer the grandeur of the composition or decoration for its own sake, but the spatiality of the construction.” As in Villa Dosi Delfini, the faux architectures here open up to enlarge the physical space of their surroundings, but the result is a more composed-looking ensemble than the one his father had designed fifty years earlier: fashions and tastes had changed, and Giovanni Battista Natali had sensed the changes of the time, although perhaps to speak of neoclassicism is premature. If anything, these are quadratures that open to the airiness of the scenes by Giuseppe Galeotti (Florence, 1708 - Genoa, 1778), a figurist who attended to the frescoes in the salon, two adjoining rooms and the alcove, following an iconographic program aimed at celebrating the virtues of the Dosi family with frescoes of mythological and allegorical subjects. Unfortunately, the paintings that once adorned the palace are no longer preserved: only the empty painted frames remain. One can still perceive, however, that “immediate feeling of grandeur and pomp,” to use Trivelloni Manganelli’s words, that must have taken anyone who entered these rooms, especially in the Salone (to which the scholar referred), where Giuseppe Antonio Dosi, the promoter of the reconstruction work on the palace, had himself portrayed naked and crowned with laurel among the gods of Olympus.

As anticipated, this genre of paintings constituted the main strand of Baroque Pontremoli, where it was introduced precisely by Francesco Natali: it was not a locally born genre, but the specificity of the Lunigiana town, the scholar Rossana Bossaglia already noted, lies in the fact that in a small town such as Pontremoli is concentrated “a series of examples of a specialty which eighteenth-century Italy cultivated and developed in a splendid and spectacular way, and which represented the highest point of evolution of perspective and subjunctive painting, initiated since the fifteenth century, as a tension and then reversal of architectural-illusionistic premises.” Moreover, for the innovative and exquisitely architectural character of the quadratures of Villa Dosi Delfini, Bossaglia assigns a leading role on the national scene to Francesco Natali, trained in that Emilian environment where the genre developed earlier than elsewhere, and a connoisseur of the Perspective of painters and architects, which Andrea Pozzo published in Rome in 1693, the first treatise on perspective applied to pictorial fiction, in which is codified a theoretical foundation matured precisely in the Bolognese environment, namely, Bossaglia writes, “the assumption that the quadrature should be a mock architecture and therefore reproduce, in terms of illusory environment, the effects of real environments, the sense of tectonic concreteness, of subt, of spatial depth, keeping good the criterion of the evidence of the central focus and thus of a precise point of reference in the perspective construction, with special interest in the strong foreshortening.” However, Pontremoli was not only a city of painted architecture: it was also a lively collecting center, where paintings by the greatest Italian artists arrived. The town’s most prominent families boasted works by the greatest artists of the time in their picture galleries: from Carlo Dolci to Francesco Furini, from Francesco Cairo to Bernardo Cavallino, from Panfilo Nuvolone to Giuseppe Bottani, and one should not forget the artistic heritage of the town’s churches, where one comes across works by Domenico Fiasella, Luca Cambiaso, Giambettino Cignaroli and even a Crucifixion by Guido Reni (an attribution long debated: today, however, there is a tendency to assign the work to the hand of the master), which can be admired inside the church of San Francesco.

It was, moreover, precisely from the churches that the renewal of Pontremoli began in the mid-seventeenth century: in 1644 the oratory of San Lorenzo was consecrated, in 1670 restoration work was begun on the church of San Niccolò, between 1670 and 1688 work was proceeded with the demolition and reconstruction of the churches of San Geminiano and Santa Caterina, while in 1699 the church of Santa Maria del Popolo, the construction of which had begun in 1636, designed by the Cremonese architect Alessandro Capra, and finished in the 1680s, was recognized as “insigne collegiata,” and finally, in 1787, it became a cathedral with the elevation of the city to an episcopal see. The Cathedral of Pontremoli is the largest Baroque building of worship in the city: it has the typical layout of Jesuit temples, that is, with a large single nave, side chapels, a short transept, and a vast and luminous dome, in this case designed by Ticino architects Marco Antonio Grighi and Domenico Garusambo between 1681 and 1683. The nave had been entirely frescoed by Francesco Natali at the end of the 17th century: its decoration, however, was replaced with stucco during the 19th century, just as the facade is also 19th-century. Even though it is no longer possible to admire all of Natali’s frescoes (only the figures of St. Rose of Lima and St. Geminianus remain), Pontremoli Cathedral stands out as one of the most magniloquent products of the great season of Pontremoli Baroque, not least because of the many works it houses: A Birth of the Virgin by Giovanni Domenico Ferretti, a Visitation by Vincenzo Meucci, an Annunciation by Giuseppe Bottani, Saint Neighbor by Pierre Subleyras, and the Oath of the Municipal Council of Pontremoli by Giovanni Battista Tempesti can be admired there.

If, however, one moves to the nearby church of San Francesco, it will be possible to see a still intact example of Francesco Natali’s great Baroque decoration: these are the chapels of St. Anthony and St. Ursula, where the great quadraturist painted faux altars with twisting columns arranged within faux architecture that develop upward, ending on the ceiling with oculi open to the sky, where one witnesses the apparition of saints. The decoration of St. Francis dates from 1725-1726: on the other hand, Natali’s interventions in the Sanctuary of the Santissima Annunziata, where the artist worked in the Sacristy and the Chapel of St. Nicholas of Tolentino, are slightly earlier, though not yet datable with certainty. In the latter space Natali’s visionary flair opens up to show the appearance of the saint in a luminous sky that we glimpse beyond the majestic painted architecture, while in the vault of the Sacristy the artist, Bertocchi writes, “is all delicacy and masterfully succeeds in creating the illusion of space opening up beyond the ceiling; the colors themselves, from light blues, to pinks, greens, lilacs, and browns, so variously shaded and interspersed, never too violent, softened by the light bursting from two large windows, help the eye to escape upward along with the slender columns perfectly foreshortened up to the central opening, artistically contoured by a circle of leaves, the last contrast to the gaze that sinks into the vision of a dome that seems so far away.” Then, among the religious buildings, it is worth mentioning theOratory of Our Lady where, in addition to some canvases by Alessandro Gherardini and Giuseppe Galeotti, it is possible to admire the fresco decoration executed by Sebastiano Galeotti (Florence, 1675 - Mondovi, 1741) within the quadratures of Giovanni Battista Natali: these are frescoes with biblical subjects executed between 1735 and 1738 and can be placed among the best products of the brush of the Florentine artist who was among the most important fresco painters of his time.

Finally, among the most noteworthy palaces of Baroque Pontremoli, we should certainly mention Palazzo Petrucci, with the interventions of Francesco and Giovanni Battista Natali on the piano nobile, Palazzo Negri, defined as a “house of beautiful appearance” in Antonio Contestabili’s Descrizione delle Chiese e dei Palazzi di Pontremoli, already in existence in 1673 (two years later Gherardini was called to fresco the hall, which no longer existing as the palace was later rebuilt), and with a façade reminiscent on a smaller scale of that of the Palazzo Barberini in Rome, and Palazzo Pavesi Ruschi, one of the most striking buildings in the historic center with its three façades enlivened by curvilinear cornices and stringcourses, one of which, the main one, overlooks Piazza della Repubblica, the heart of Pontremoli’s historic center. The palace was bought by Geronimo di Lorenzo Pavesi in 1688 (it had previously belonged to another important Pontremolese family, the Belmesseri), after which, between 1734 and 1743, it was entirely renovated by his grandsons Giuseppe, Francesco and Paolo, who made it take its present form, unifying the previous bodies of the building into a single whole, divided, however, into two parts, with two courtyards, two staircases and two representative apartments, formerly belonging to Francesco and Giuseppe Pavesi. The frescoes are due to Giovanni Battista Natali and collaborators: these include the aforementioned Antonio Contestabili (Piacenza, 1716 - Pontremoli, 1790), Natali’s nephew and another illustrious name in Pontremoli Baroque. The gallery of Palazzo Pavesi Ruschi is the palace’s most sumptuous room: “it is painted as a colonnaded courtyard,” Isa Trivelloni has written, “because the architect, constrained by the pre-existences, could not realize in the palace an adequate gallery, bright and equipped with large windows overlooking the courtyard (as, for example, in Palazzi Dosi and Negri). That is why he painted the largest hall, which serves as a hallway to the other rooms on the piano nobile (and is called La Galleria), with large columned compartments that open onto visions of landscapes: on both sides, four columns and two corner pillars support the impost of the vault; the colonnades are treated in faux marble in green, have gilded capitals and are banded with roses [...]. The decoration of the vault is structured asu three planes, with corbels supporting a nimble balcony, beyond which green marble columns support a stucco ceiling, over which the skylight opens, beyond which a dome can still be glimpsed in the distance; the colors are blue and gold, white, verdino. In the corners, on the spandrels of the vault, four beautiful ovals frame views and landscapes. Next to the salon, a drawing room frescoed only in the vaulting, with intertwining and chasing balustrades and balconies, whose vertical walls are still wallpapered with the fabulous damask that the Pavesi family produced and traded in, physically takes us back to the eighteenth-century dimension.”

Some of these places can be visited regularly today (this is the case with the Duomo and San Francesco and Villa Dosi Delfini), while others can be visited by appointment only (Palazzo Dosi and the Santissima Annunziata), and still others cannot be visited because they are private.

The season of Pontremolese Baroque can be considered closed with the works executed by the Lombard Giuseppe Bottani (Cremona, 1717 - Mantua, 1784) for Pontremolese collectors and for town churches. Bottani was the major representative of a classical current that, from the mid-18th century, began to spread in Pontremoli, helping to steer the tastes of the town oligarchy toward the nascent neoclassical movement. For Pontremoli another epoch was opening, no less relevant since important figures such as the French-Piedmontese Jacques Berger and the Tuscan Giuseppe Collignon came to town, and the town also managed to produce an interesting artist such as Pietro Pedroni, a native of Pontremoli although trained in Parma and then settled in Florence (Collignon himself was his pupil at the Academy of Fine Arts in the Tuscan capital). Gone, however, were the glories of what was literally the golden century of Pontremoli Baroque, the coordinates of which could be traced between 1650, the year of the town’s entry into the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, and 1750, the year of the completion of the paintings on the piano nobile of Palazzo Dosi Magnavacca.

Pontremoli was also beginning to experience a gradual loss of prestige, which went hand in hand with the city’s loss of commercial importance: from the decline that had begun in the Napoleonic era, the town would never recover, so much so that in 1847 Pontremoli, in implementation of the Treaty of Florence concluded three years earlier between the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, the Duchy of Modena and Reggio, and the Duchy of Parma and Piacenza, passed, along with the entire upper Lunigiana, to the Parmesan states, which in turn ceded Guastalla to Modena (Florence in return obtained from Modena the relinquishment of Pietrasanta and Barga). Even at that time the Parmesans considered the treaty disadvantageous for them, since Pontremoli was no longer the important and flourishing economic and commercial center it had been until a few decades earlier. The most splendid season had passed: however, an indelible trace of it remains today in the heart of the city.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.