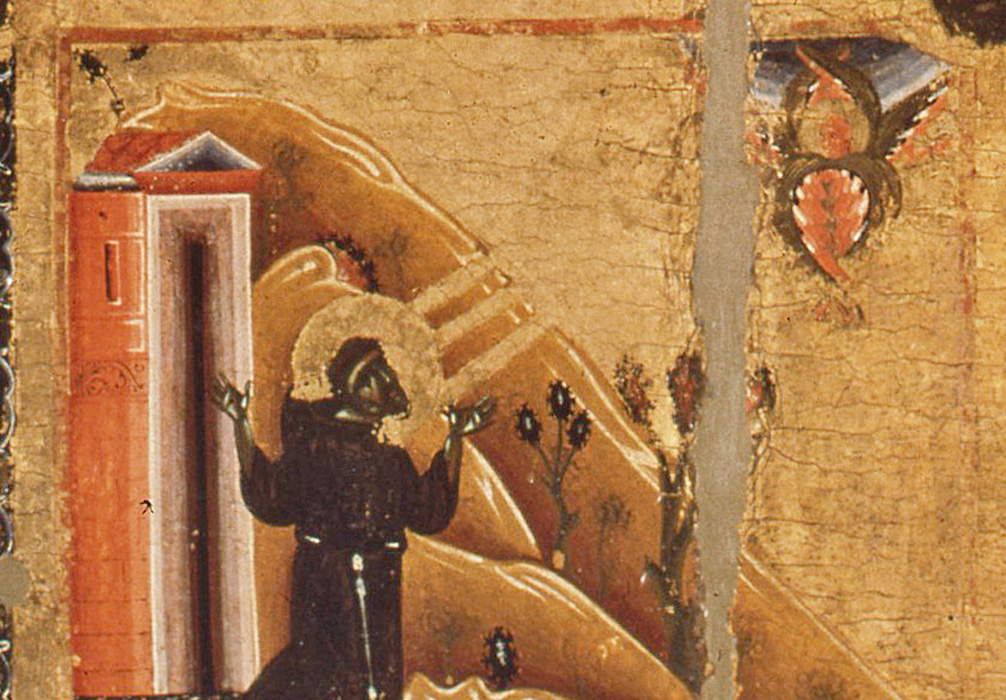

St. Francis appears kneeling, on the barren land in the territory of La Verna, Casentino: behind him steep cliffs and sparse vegetation, a few tufts of grass and a tree near the crest of the mountain, offered to him as a hermitage by Count Orlando Cattani. Just below the summit is the hermitage’s first church, dedicated to St. Mary of the Angels, and in the upper right-hand corner a seraphim from which come the rays of light that strike Francis, leaving him imprinted with the stigmata, the wounds that the sufferings of the Crucifixion caused Christ to have on his body (there are five: two on his hands, two on his feet, and one on his side). This is the way the episode of the Stigmata of St. Francis is depicted in a precious panel painting from 1240-1250, a work attributed after a long critical debate to the Master of the Cross 434 and conserved at the Uffizi, which made it the protagonist of the first stage of the Uffizi project spread outside Tuscany, the exhibition inTORNO a Francesco (Assisi, Sala ex Pinacoteca, from November 14, 2021 to January 6, 2022, curated by Giulio Proietti Bocchini and Stefano Brufani).

According to Catholic mysticism (the stigmata, however, are not a dogma), some believers would be able to receive the signs of Jesus’ sufferings when they come into spiritual union with Christ, identifying with him. St. Francis (Giovanni di Pietro di Bernardone; Assisi, 1181/1182 - 1226) is, according to religion, the first saint to receive the stigmata. According to his hagiography, the saint, in September 1224, while on the mountain of La Verna, finding himself in a state of perfect union with Christ, allegedly received the stigmata through a seraphim. In the Legenda maior, one of the earliest hagiographies of the saint, compiled in 1263 by Bonaventure of Bagno regio (Bagnoregio, 1217/1221 circa Lyon, 1274), the episode is narrated as follows (here in Simpliciano Olgiati’s translation): “Two years before he rendered his spirit to God, after many and various labors, divine Providence drew him aside, and led him to a lofty mountain, called the mountain of Verna. Here he had begun, according to his custom, to fast Lent in honor of St. Michael the Archangel, when he began to feel himself inundated with extraordinary sweetness in contemplation, kindled by brighter flames of heavenly desires, filled with richer divine bestowments. [...] The indomitable fire of love for the good Jesus erupted in him with flames and flames of charity so strong, that the many waters could not extinguish them. The seraphic ardor of desire, therefore, ravished him into God, and a tender feeling of compassion transformed him into the One who wanted, through an excess of charity, to be crucified. One morning, at the approach of the feast of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross, as he was praying on the side of the mountain, he saw the figure as of a seraphim, with six wings as bright as they were fiery, descending from the sublimity of the heavens: it, with very rapid flight, holding itself hovering in the air, came near the man of God, and then there appeared between its wings the effigy of a crucified man, who had his hands and feet spread out and confined on the cross. Two wings rose above his head, two stretched out to fly, and two veiled his whole body. At that sight he was greatly astonished, while joy and sadness flooded his heart. [...] But from here he understood, at last, by divine revelation, the purpose for which divine providence had shown that vision to his gaze, namely, that of making known to him in advance that he, the friend of Christ, was about to be transformed wholly into the visible portrait of Christ Jesus crucified, not by the martyrdom of the flesh, but by the fire of the spirit. As he disappeared, the vision left a wondrous ardor in his heart and equally wondrous marks it left imprinted in his flesh. Immediately, in fact, in his hands and feet, nail marks began to appear, like those he had just before observed in the image of the crucified man. The hands and feet, right in the center, were seen to be confined to the nails; the nail heads protruded on the inside of the hands and the top of the feet, while the tips protruded on the opposite side. The nailsheads in the hands and feet were round and black; the tips, on the other hand, were elongated, bent backward and as if riveted, and came out of the flesh itself, protruding over the rest of the flesh. The right side was as if pierced by a spear and covered with a red scar, which often emanated holy blood, soaking the cassock and underpants. He saw, the servant of Christ, that the stigmata imprinted in such an obvious form could not remain hidden from his closest companions; he feared, nevertheless, to put the Lord’s secret in public and was torn by a great doubt: to tell what he had seen or to keep silent? He called, therefore, some of the friars and, speaking in general terms, explained the doubt to them and asked for advice. One of the friars, Enlightened, by name and grace, guessed that the saint had had an extraordinary vision, due to the fact that he looked so stupefied, and said to him, ’Brother, know that sometimes divine secrets are revealed not only to you, but also to others. There is, therefore, good reason to fear that if you keep hidden what you have received for the benefit of all, you will be found guilty of concealing the talent.’ The saint was struck by these words and [...] with much fear, reported how the vision had occurred and added that during the apparition the seraphim had told him some things, which in his life he would never have confided to anyone. Evidently the speeches of that holy seraphim, who had admirably appeared on the cross, had been so sublime that men were not permitted to utter them. Thus the true love of Christ had transformed the lover into the very image of the beloved.”

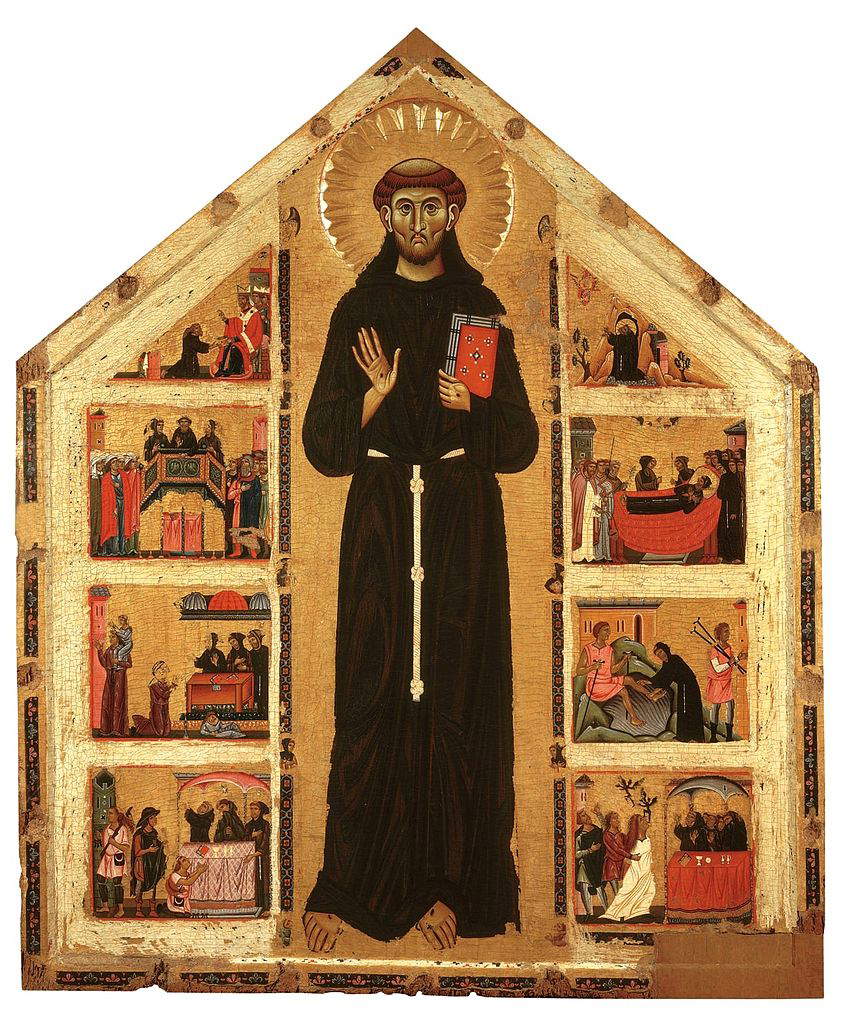

The miracle of the stigmata was made known shortly after Francis’ death by Brother Elias, his confrere, who mentioned it in the letter in which he announced to Gregory IX and the Franciscan provinces the departure of the Assisiate. Instead, the first “public” narrative, so to speak, of the event, reported in the biography of Francis written by Thomas of Celano, dates back to 1228. The Uffizi panel is one of the earliest attestations known to us in painting of the episode concerning the saint’s life, as well as being probably the earliest depiction not found in a fresco or panel where more than one story of Franciscan hagiography is represented: here, the episode of the Stigmata occupies the entire panel, which was originally perhaps part of a diptych, or could even have been an autonomous work, thus an object of particular value, produced for devotional purposes. We do not know where it came from: what is certain is that it is a particularly fortunate panel, since in Paris, in 1266, the Franciscan General Chapter gave orders to destroy all images of St. Francis, and the Uffizi work evidently survived the operation. The work is first recorded on September 22, 1863, when Florentine merchant Ugo Baldi donated the panel to the Accademia di Belle Arti in Florence, and it has not left the Florentine public collections since (it was finally transferred to the Uffizi in 1948).

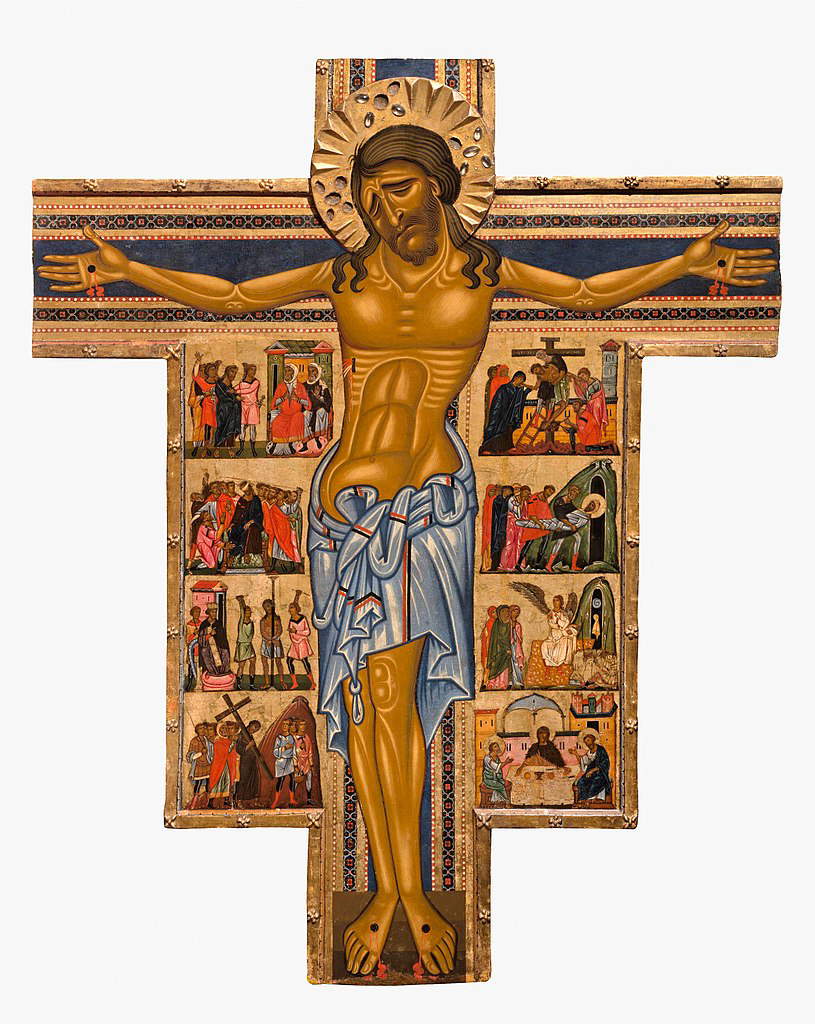

Just as we do not know where the panel came from, similarly we do not know the name of its author. Pietro Toesca, in 1927, assigned it to the Lucchese Bonaventura Berlinghieri (Lucca, c. 1210 - c. 1287), author of the first known painting in which episodes from the life of the Poverello of Assisi are depicted, the panel with St. Francis and stories from his life in the church of San Francesco in Pescia, where we also note the episode of the stigmata. However, similarities can be noted with the episode of the Stigmata of St. Francis painted in the altarpiece by the so-called Master of St. Francis Bardi, the author of a panel preserved in the church of Santa Croce in Florence (although today some of the most authoritative critics, above all Angelo Tartuferi, tend to assign it to Coppo di Marcovaldo, a great personality of mid-13th-century Florentine art): indeed, according to Mina Gregori, the Uffizi panel is “the sure work of the author of the great altarpiece placed on the altar of the Bardi Chapel in the church of Santa Croce.” Before that, Edward B. Garrison, the art historian who coined the name “Master of the San Francesco Bardi,” referred both the Santa Croce panel, the Uffizi tablet, and, albeit dubiously, the Uffizi Cross 434 to the latter. Cross 434 is another of the enigmatic works in our medieval art history, the work of an author identified as an artist active in Florence, but trained in the Lucca area (an ascendancy, however, also noted by Gregori for the Uffizi tablet) and indebted to the ways of Berlinghiero Berlinghieri (Volterra, c. 1175 - Lucca?, 1235/1236).

Miklós Boskovits, on the contrary, saw substantial differences between the painter who had painted the St. Francis of the Bardi Chapel and the author of the Stigmata di san Francesco: the Hungarian scholar was in fact the first to formulate the name of the Master of the Cross 434 for the Stigmata, an attribution later confirmed by Angelo Tartuferi on several occasions (in 2000, 2004 and 2007) and by Francesca Pasut, and accepted by the Uffizi Galleries. “Conspicuous” differences, Boskovits wrote in his work The Origins of Florentine Painting, 1100-1270 (written in collaboration with Ada Labriola and Angelo Tartuferi), “both in the arrangement of the individual elements of the scene and in the choices of colors and decorations. There is no trace, in the San Francesco Bardi altarpiece, of the preference for the use of various shades of the same color, of toned-down chromatic harmonies along with brighter notes, limited to a few areas of the composition, which are decisive traits of the Uffizi panel. The Santa Croce altarpiece is the product of an artist of less controlled talent, intolerant of rules, which must therefore be analyzed as a work in its own right. Here it is necessary merely to say that I cannot see a place for the San Francesco Bardi in the catalog of the Master of the Cross 434, while on the contrary the Stigmata in the Uffizi seem to me a characteristic product of that painter, executed in a period placeable between the Cross itself and the Pistoia altarpiece [now in the city’s Museo Civico, ed.], around the second half of the 1940s.”

Also agreeing with an early dating is Chiara Frugoni, who in 1993 related the Uffizi Stigmata to the Bardi panel (which she believed to be earlier) in order to point out how, on the iconographic level, the Florentine museum panel features the attribute of the cross of Christ behind the seraphim, which is absent in the Santa Croce altarpiece. Stylistically, we are faced with a work that, wrote the curators of the exhibition inTORNO a Francesco di Assisi, is presented with an “intimate and spiritual style of Byzantine matrix, while favoring frontal perspective and two-dimensional schematization of forms,” and is presented with “new features , more realistic and refined, starting from the space, which is more defined thanks to the clear demarcation of the rocky boundaries of the promontory from the gold background, as well as from the presence of vegetal elements emerging from the rock, to the accurate rendering of the saint’s robe.” The revival of traditional patterns of Byzantine matrix updated, however, on the basis of a space that becomes more realistic characterizes Lucchese painting of the time, a sphere to which, as mentioned, the Master of 434 had to look.

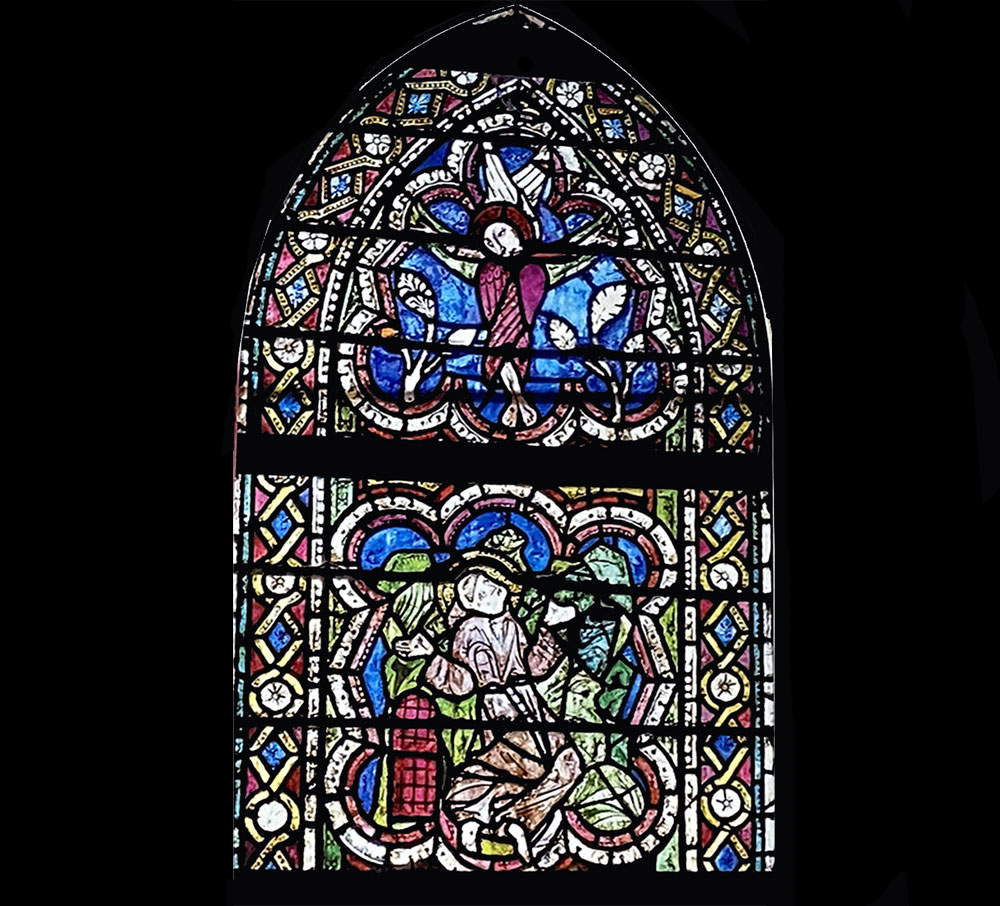

The depiction of the episode of the Stigmata that we see in the Uffizi panel is rare, but there are other contemporary or slightly later attestations, and a couple of them are found in Assisi itself. These are a stained glass window and a fresco both attributed to the so-called Master of St. Francis, another artist active in the Umbrian site in the mid-13th century. The stained-glass window is part of what is now the most complete Italian series of medieval stained-glass windows (despite extensive remodeling), that of the Upper Basilica of St. Francis. The oldest are those of the apse, which probably followed the consecration of the basilica by a short time (1253), and which are attributed to German craftsmen, while the stained-glass window from which the stigmata come is the one with the Stories from the Life of St. Francis, which is located in the first window of the right wall of the nave, attributed as mentioned to the Master of St. Francis and made in all likelihood after 1263, since the subjects appear to owe a strong debt to the Legenda Maior of Bonaventure of Bagnoregio. The stained glass window was first attributed to Cimabue, while it was Henry Thode who formulated the attribution to the “Master of St. Francis,” a designation he coined.

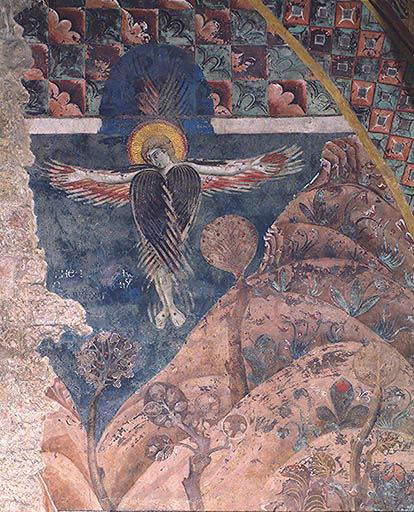

In the stained-glass window, the saint is kneeling, palms facing upward, as in the Uffizi panel, although the two works are not in a relationship of dependence, they are nonetheless interesting as among the earliest examples of the depiction of the episode of stigmatization. The same is true of the other painting attributed to the Master of St. Francis, the fragmentary fresco that is part of the scene with St. Francis receiving the stigmata and is found among the remains of the pictorial cycle painted along the nave of the lower basilica of St. Francis, which was partially destroyed a few decades after its completion, when the arches leading to the chapels were opened. Very little remains of the depiction: only the seraphim and a piece of the Verna landscape, while the figure of the Poverello has been completely lost. Nevertheless, it is a relevant work because it belongs to the oldest decoration of the church, executed around 1260 by the Master of St. Francis, who painted stories from the life of Christ on one side and stories from the life of St. Francis on the other.

One of the most poignant episodes in the life of St. Francis and among the most spiritually significant, that of the stigmatization would shortly thereafter also become one of the most present in the history of art. The miracle of the stigmata had made St. Francis an alter Christus (as Bonaventure of Bagnoregio himself described him) that made his faith journey different from that of other saints (St. Francis was canonized in 1228). It was an event that also took on strong theological connotations, since the miracle was the way in which it was possible to demonstrate Francis’ sanctity and edify his image (although for Thomas of Celano Francis’ sanctity was given above all by his works), and philosophical meanings, since the miracle is also the means by which Francis understands the meaning of the cross (which also appears to him in the vision of the seraphim) in order to come to the full knowledge of Christ.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.