by Federico Giannini, Ilaria Baratta , published on 06/07/2015

Categories: Works and artists

/ Disclaimer

Bernardo Bertolucci's The Dreamers, a cinematic masterpiece of the early 2000s, counts several artistic references: here are some of the most interesting ones

For anyone who was a kid in the early 2000s, Bernardo Bertolucci ’s The Dreamers has always constituted one of the “cult films,” as they say. It may be because it introduced the world to the beauty and sensuality of Eva Green, the lead actress; it may be because the three boys around whose story the film’s plot unfolds were about the age we who were watching the film were; it may be because of theexplicit eroticism with an initiatory flavor with which the film overflows; and it may be because of the numerous cultural references: it may be, therefore, for all these reasons that The Dreamers has remained etched in our minds and memories.

Several critics would say that the uprisings of ’68 are but a pretext, which remains distant and is confined to the streets of a Paris in full turmoil, to tell the story of the three main characters, three boys little more than teenagers who bond in a menage à trois with a morbid flavor: because two of them are twin brothers, but this does not prevent them from experimenting with an eroticism that is yes refined and yes rather tenuous (and, of course, incestuous), but still certainly not shy or submissive. The revolution, then, would merely constitute a backdrop against which to weave the story of two brothers who take advantage of their parents’ absence from home to give free rein to their urges by involving an American boy they met thanks to their shared passion for cinema (and numerous, in fact, are the cinematic references). But if the revolution was just a pretext, what is the point of dotting the film with numerous artistic quotations that refer back to the revolution itself?

In one of the most famous scenes, the three main characters attempt to break the record for running through the Louvre, an explicit reference to the 1964 film Bande à part, in which we first witness this bizarre competition: Isabelle (Eva Green), Théo (Louis Garrel), and Matthew (Michael Pitt) manage to beat the record set in Bande à part, lowering it by seventeen seconds. The fact that the director dwells on Jacques-Louis David ’s Oath of the Horatii is probably not only due to the fact that in Bande à part we see the same shot, and probably not even to the fact that there are three Horatii, like the protagonists in Bande à part and like the protagonists in The Dreamers. The Oath of the Horatii, although painted a few years before the outbreak of the French Revolution, nonetheless constituted a point of reference for many of those who hoped for a renewal of society, so much so that there were not a few who, when the work was exhibited at the Paris Salon in 1784, paradoxically saw it as a kind of critique of the very circles that had commissioned it: what was extolled were civic virtues, loyalty to the state, and attachment to the values that constitute the foundation of society. And many revolutionaries felt close to the ideals embodied by the three siblings depicted in the painting.

|

| Isabelle, Théo and Matthew run through the corridors of the Louvre. |

|

| The camera lingers on David’s Oath of the Horatii. |

The revolution appears somewhat “actualized” when, during one scene, in Isabelle and Théo’s house we see a reproduction of Eugène Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People, the very famous painting made to celebrate the so-called July Revolution of the"Trois Glorieuses" of 1830, when the people of Paris rebelled against the repressive policies of Charles X. Actualized because on the face of Liberty, Isabelle and Théo attached a photo of Marilyn Monroe: an image that, in turn, constitutes an artistic homage, this time to Andy Warhol. The revolution, in the Sixty-Eight, has also moved to the level of costume, the revolution becoming even more something close to the masses, because it appropriates one of its icons, the revolution eliminates society’s sexual inhibitions: all the more so that, during one scene, as a token for losing at a game, Théo forces Matthew to deflower his consenting sister right under the reproduction of Delacroix’s painting. The young American, initially reluctant, will later become involved: in the background, from the open window, come the cries of rioters running through the streets.

|

| Delacroix’s image of Liberty with Marilyn’s picture affixed to it. |

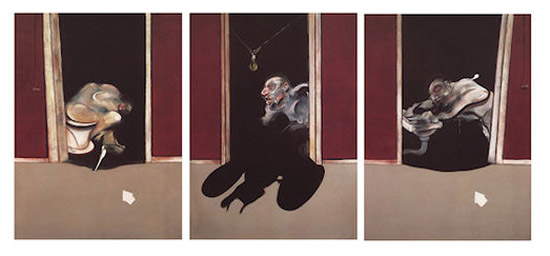

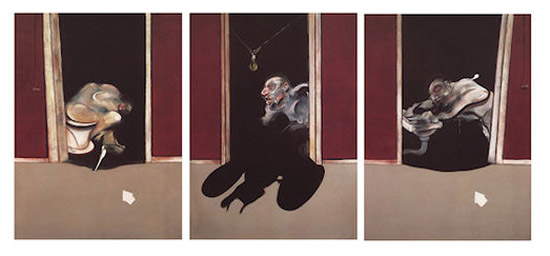

Isabelle and Matthew later become lovers, and they do not fail to involve Théo in their “experiments.” Famous are the scenes in which they share intimate moments: in one of the most famous ones, the three share a bath in a tub, with three mirrors on the rim reflecting their image, reminiscent of Francis Bacon’s triptychs. And again, toward the finale, we see the boys sleeping, naked together, in an image that evokes, through Eva Green’s voluptuous forms, the odalisques of Ingres, and on the other, a painting like Delacroix’s Death of Sardanapalo, both for its exotic setting, sensuality and nudity, and its reference to the theme of suicide. Just as Sardanapalo decided to kill himself along with his concubines and servants, similarly Isabelle, after realizing that her parents have discovered the “games” of the three boys, decides to flood the room with gas and end their brief existence. It will be, however, a providential stone thrown by protesters that will save them and call them back to the streets in the midst of a sedition. And it will be in the streets that Matthew will realize the gap that separates him from the two brothers.

|

| Isabelle, Théo and Matthew in the bath. |

|

| Francis Bacon, Triptych, MayJune 1973 |

|

| Isabelle, Théo and Matthew in bed |

|

| Eugène Delacroix, The Death of Sardanapalo. |

But perhaps the best known scene is when Isabelle bursts, sensual and sinuous, into Matthew’s room to the notes of The spy by The Doors. Her arms are covered by long black gloves: the gloves blend into the half-light and the figure of Eva Green, standing still in the doorway of the room, echoes the Venus de Milo. It is perhaps the main reference to art in the entire film. “I always wanted to make love to the Venus de Milo,” whispers Matthew as soon as he notices Isabelle’s presence. The girl approaches, and Matthew begins to perform oral sex on her. “I can’t stop you,” Isabelle says. “I don’t have arms.”

|

| Eva Green as the Venus de Milo |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.