Art criticism: developments in formalism (Roger Fry, Lionello Venturi)

In the last installment of our short little history of art criticism we had talked about the theory of pure visibility and the origins of formalism: in this new “installment” we will see how some great art historians approached formalism. We will see, in particular, the achievements of two big names, namely Roger Fry and Lionello Venturi, and we will reserve the right to devote a further article shortly to Bernard Berenson, another important scholar who was influenced by formalist theories.

Let us start from a point of contact with what had been said last time: in brief, we had seen how the Swiss scholar Heinrich Wölfflin had proposed five pairs of fundamental concepts in art history that would determine the ways of an artist. Art history would be a kind of continuous “alternation” of opposing principles that, in certain styles, find application as reactions to earlier forms of expression. In 1921, Englishman Roger Fry (London, 1866 - 1934) published a review of Wölfflin’s book Kunstgeschichtliche Grundbegriffe (Fundamental Concepts of Art History), which was titled The Baroque: In his essay, Fry argued that, just as neoclassicism had been a reaction to the Baroque, similarly postimpressionism (a term coined by Fry himself and which has had a very remarkable fortune in the study of art history, such a fortune that even today the experiences of the artists who came immediately after the Impressionists are identified with this term: Seurat, Van Gogh, Gauguin, Cézanne... ), with its character devoted to linearism, took the form of a reaction to the pictorial style typical, instead, of Impressionism. Roger Fry’s aesthetics derive precisely from Wölfflin’s formalist aesthetics: for Fry, too, a work of art is, first and foremost, a collection of lines, shapes and colors, and it is therefore on the formal elements of the work (and not on the content that the work represents) that the scholar should base his judgment. Fry was very fascinated byAfrican art: it is worth pointing this out because this interest of Roger Fry’s can provide us with an example to better understand formalist aesthetics, since, when we are confronted with a work of African art, our impressions are based on the outward qualities of the work, rather than on what the work represents or on the message, incomprehensible to most, that the artifact we are looking at is meant to convey.

|

| Roger Fry |

Of course, for Fry, too, art is not imitation, but an activity of free creation. In an essay titled The French Post-Impressionists, published in 1912 as a preface to the catalog of the second exhibition of Post-Impressionist painters, Fry wrote, referring to Cézanne and his followers, “these artists do not seek to imitate form, but to create it; they do not seek to imitate life, but seek an equivalent of life. The artist is driven to the study of nature by his own curiosity, but from this study he will derive structures that he will employ, through his own mode of expression, in his works to create, precisely, ”an equivalent of life." This ability to create a system of logical structures was particularly appreciable, according to Fry, in the art of the Florentine painters of the fifteenth century, to whom the English scholar devoted much of his work, trying, moreover, to find a common thread uniting them with the Post-Impressionist artists (and on the relationship between Fry and the Post-Impressionists we will return shortly with a dedicated article, because the subject is interesting). It will be useful to recall that Fry, early in his career, interested as he was in the art of the so-called “Italian primitives,” wrote some interesting essays on Giotto, about which he would return to in a note in the collection Vision and Design, published in 1920. While early in his career Fry was primarily fascinated by the dramatic aspects in the art of the great Tuscan painter, in the 1920s his perspective would undergo a marked change: “it will be seen that [in the 1901 essay on Giotto] much emphasis was placed on how Giotto expressed his own dramaticism in his works. I believe that this is still true, in spite of everything [...] but I am also inclined to no longer agree with the points in the essay from which the assumption leaks out that not only might the idea of drama have inspired the artist in the creation of his form, but also that the value of the form is linked to the recognition of this idea of drama. Now it seems to me that it is possible, as a result of a more thorough investigation of our experience before a work of art, to liberate our reaction before the pure form from our reaction with respect to the associated ideas it implies.” In this passage, Fry explains how it is possible to have a reaction that pertains exclusively to the pure form, without therefore minding the “associated ideas” (the content, the drama) that are related to that form we are observing.

An example may better clarify. We are well aware of the Lamentation over the Dead Christ that Giotto painted in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua. In his 1901 article, Fry wrote that the painting’s characteristics could not be separated from the powerful drama that connotes the composition. But in 1920, the English scholar provided a quite different interpretation of Giotto’s masterpiece: he was convinced that the forms were independent of their meaning, and were therefore sufficient in themselves to move the viewer’s response. Thus, one could analyze this painting solely on the basis of its formal elements: the diagonal lines converging to the left, the solid masses of the figures crowding the scene (and the plasticity of the figures was one of the elements to which Fry attributed the most consideration in his work), the lightness of the angels in flight in the sky and their circular movement. The anecdote according to which Fry, finding himself lecturing in front of an unspecified Crucifixion in the National Gallery in London, referred to the body of Christ on the cross as this important mass, “this important mass,” should therefore come as no surprise. Yet even this seemingly outlandish approach, insofar as it may seem strange to us that an analysis should disregard the meaning of the work, would, according to the advocates of formalism, entail considerable advantages, first of all allowing a reading of the work free of the biases that might arise from the very message the work carries, or from our emotional reaction to the scene we are observing. And then it allows the expression of judgment even by those who do not necessarily know the meaning of the work: and here we return to the example of the African work of art mentioned earlier.

|

| Giotto, Lamentation over the Dead Christ (1303-1305; fresco, 112 x 73 cm; Padua, Scrovegni Chapel) |

|

| Lionello Venturi |

The formalist approach implies the fact that there is no absolute form, valid for all content: therefore, there can be no absolute formal perfection. Lionello Venturi (Modena, 1885 - Rome, 1961) was fully convinced of this, writing as follows in his essay Tradition, Taste and Form: "If the form achieved by the artist is the form of his content, it is always perfect. But in the concept of perfection lurks that of formal perfection in itself, established once and for all and elevated to the degree de la forma identified with a particular form, for example that of Phidias. Now it is easy to note that this does not make sense. Phidias’ form is perfect for Phidias’ content, just as Giovanni Pisano’s form is perfect for Giovanni Pisano’s content. Every authentic artist has his formal perfection, and outside of a perfection relative to each one, which is then a metaphor to indicate the presence of art, there is no absolute perfection." Since there is, for Lionello Venturi, no absolute perfection, the element around which his critical work revolves is what he calls "creative imagination." Fantasy is the means by which the painter succeeds in reinterpreting reality: for Venturi, too, artists do not imitate reality, but create a new one according to their sensibility.

The artist’s creativity, however, is constrained by several elements (which nevertheless can be transformed by the artist’s own creative imagination): social and environmental conditioning, moral attitudes, historical situations, cultural baggage and ideals, contingencies and whatnot. Often these elements are common to groups of artists who share an era or live in the same region. It is here, therefore, that the concept of"taste" comes into play, which Lionello Venturi reformulated in these terms in his 1926 essay Il gusto dei primitivi: “This book [...] does not look for what singles out artists, it looks for what unites them, not their art, but their taste. I don’t know if the word ’taste’ is the most appropriate to mean what I mean; I have not found a better one. And to avoid misunderstanding, I state that I mean by taste the set of preferences in the art world on the part of an artist or group of artists. Michelangelo prefers plastic form and the naked body, he despises portraiture and landscape, and so on: this is Michelangelo’s taste. Titian prefers color effects and shimmering clothes, he loves portrait and landscape and the like: this is Titian’s taste.” And to further clarify the concept, Venturi wrote in his 1936 History of Art Criticism, “None of those preferences are identified with creativity. They accompany the formation of the work of art, they are included in the work of art, but when the work of art is perfect they result transformed by creativity, and can be recognized only if detached from that whole, from that character of synthesis, which is proper to creation. These constructive elements of the artistic fact are of various natures, from technique to the ideal, but they have a common character in the face of the synthesis, the creation of the work of art. That common character was many years ago called ’taste’ by me.”

|

| Niccolò di Pietro, San Lorenzo (c. 1420; panel, 62 x 22 cm; Venice, Gallerie dell’Accademia) |

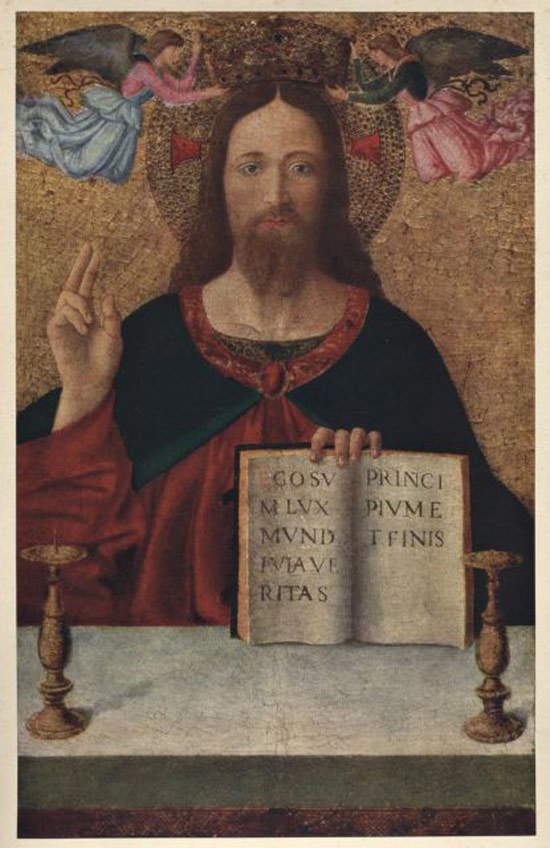

An example of how these principles guided Lionello Venturi in the attribution of works of art (an activity that the scholar conducted throughout his career) is offered by a catalog of the Gualino collection in Turin, exhibited at the Galleria Sabauda, which the art historian made known with this 1928 publication. In describing a Blessing Christ, which he believed to be the work of Melozzo da Forlì, Venturi praised Melozzo’s ability to combine Byzantine hieraticism, identified in certain features such as the “rigidity of the image of Christ , the ”golden background“ and the ”chromatic richness“ typical of Byzantine mosaics, to the Renaissance ”human conception of the world“ revealed by the ”perspective rigor of the parapet“ and by the candelabras that drop their shadows on the marble of the parapet ”with impeccable and absolute pierfrancescana justness." The artist’s creativity, in essence, acts on typical elements of taste (on the one hand the grandiose and solemn one that refers to Byzantine mosaics, on the other the Renaissance one) to make a synthesis that creates, through forms, a new reality. For the sake of completeness, we can say that not all scholars accepted the attribution of the Turin Christ: already in the famous exhibition on Melozzo in 1938 a weakness in the structure was identified, when compared with other works by the Romagna artist, such as to suggest a follower rather than the master (and in fact today the painting is considered the work of an artist of the circle). There are, however, attributions formulated by Venturi that still endure to this day: we can cite, for example, an early attribution (included in a 1907 work by the scholar, Le origini della pittura veneziana: 1300-1500, which takes the form, in practice, of his first study) concerning a San Lorenzo preserved in the Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice, and assigned by the scholar to the Venetian painter Niccolò di Pietro. The correctness of Venturi’s attribution was recently reaffirmed on the occasion of the Florentine exhibition La fortuna dei primitivi (2014), in which the Venetian work was on display.

|

| Follower of Melozzo da Forlì, Christ Blessing (second half of the 15th century; panel, 112 x 73 cm; Turin, Galleria Sabauda) |

In conclusion, one last note is necessary to better frame the figure of Lionello Venturi. For the great scholar, the artist’s creative imagination is always free (not by chance, one of his most important essays is entitled Per la libertà della fantasia creatrice): consequently, it cannot be caged in preconstituted schemes or, even worse, instrumentalized. From this conception of art probably originates Lionello Venturi’s civil commitment, which led him, in 1931, to refuse to swear allegiance to the Fascist regime, together with a small group of intellectuals. The refusal would have meant the loss of his professorship at the University of Turin, where the scholar was teaching at the time: but, after all, the oath was not compatible with his principles. Thus the scholar wrote, to justify his refusal, to the rector of the Piedmontese university: “it is not possible for me to commit myself to ’form citizens devoted to the Fascist regime,’ because the ideal premises of my discipline do not allow me to make propaganda in the school for any political regime.” Forced therefore into exile, and returning to Italy only after the end of World War II, Lionello Venturi is also remembered today for his remarkable ethical stature, which went hand in hand with his critical and professional stature.

Reference bibliography

- Andrew Leach, John Macarthur, The Baroque in Architectural Culture, 1880-1980, Routledge, 2015

- Angelo Tartuferi, Gianluca Tormen (eds.), La fortuna dei primitivi, exhibition catalog (Florence, Galleria dell’Accademia, June 24-December 8, 2014), Giunti, 2014

- Mascia Cardelli, The aesthetic perspective of Lionello Venturi, Le CÃ riti Editore, 2004

- Roger Fry, Vision and Design, edited by J.B. Bullen, Dover Publications, 1999

- Jurgis Baltruaitis, Maddalena Mazzocut, The paths of forms: texts and theories, Bruno Mondadori, 1997

- Christoph Reed, A Roger Fry Reader, University of Chicago Press, 1996

- Lionello Venturi, History of Art Criticism (ed. 1964), Einaudi, 1964

- Lionello Venturi, The taste of the primitives, Zanichelli, 1926

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.