The current historical moment advocates a reflection on some themes referable to the perception of landscape and artistic language, in the hope of delving into new methods of investigation and on the case of re-discussing some that are far from exhausted. The relationship between art and the surrounding space has already incited a heated cultural debate in the years immediately following World War II, in light of the new formal considerations on art and the scenarios triggered by the situationist experiences coined overseas, such as environments, happenings, and land-art.The Italian artistic trend of the 1960s-1970s is certainly interesting in its spatial and landscape relationship because it is in direct confrontation with a permanent historical and cultural load both in memory and in the physicality of everyday life: the urban and naturalistic architecture of the Italian context reflectsa unicumstillvalid and inescapable today for the contemporary artist, who is aware of how much his own research (whether objectual or conceptual) must touch the surrounding spaces and even synchronize them temporally in the stylistic overlap inevitably spent in the Italian landscape.

The decoding of the physical space of galleries and museums led the artist to confront the outside world in a dimensional and performative crescendoinerentto the work; the artistic environment took consensus from a social, political and cultural perspective, quantifying aesthetics to the temporal process included in the making of the work, often ephemeral for actuative or even idealized reasons. Noting how many Italian artists effectively sensed some international background (see Luca Maria Patella’s work, particularly Terra animatadel1967, ahead of Land Art), the certainly most emblematic case to designate the beginnings of Environmental Art was Volterra ’73, curated by Enrico Crispolti.

Starting with promotional intentions that were decisive to the setback suffered in the post-World War II period by the artisanal industry linked to alabaster working, the event proved to be a surprising opportunity to put into action all those issues buzzing around art since the 1950s, issues dear to Crispolti, such as the active participation of the public userand the social utility of artistic events. The variety of the proposal became the hinge on which the semantic meanings of the term environmental revolved, yet with the operators well aware of what was the indispensable element of a city: the population.

The artists intertwined lives and ideasforwhat was going to be defined as a crucial point in artistic historiography, alternating playful moments with real community apologies; recall La PilladiUgo Nespolo’s enormous pill-fetish set on fire, and its timely j’accuseallesuffocating and drug-dependent conditions suffered by the patients of Volterra’s psychiatric hospital. In essence, the very definition of “Environmental Art” was being outlined , in its marked dialectical character, not solely between the work and the surrounding space (i.e., not only a sculptural question) but primarily a collective confrontation, for a plastic investigation where the principles of Relational Aestheticsthatwould be formulated by Nicolas Bourriaud were already being glimpsed.

|

| Luca Maria Patella, Animated Earth (1967) |

|

| Ugo Nespolo, photogram of La Pillola (1973) |

|

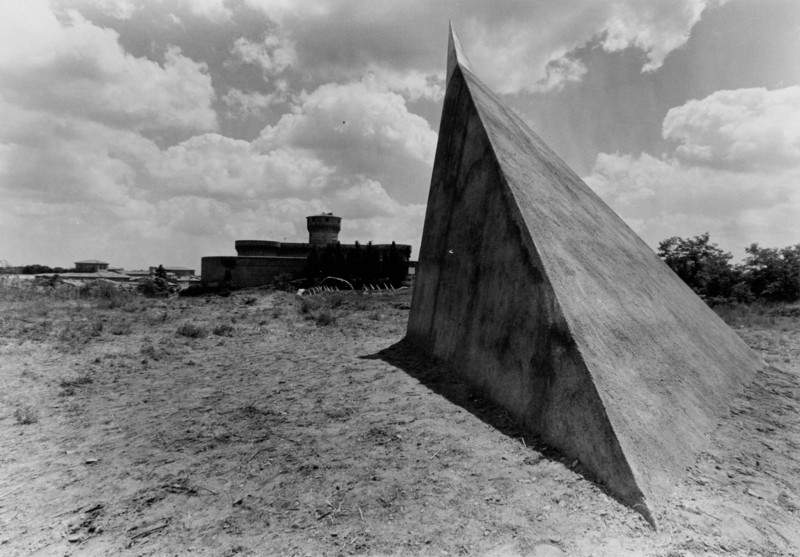

| Speech by Mauro Staccioli at Volterra ’73 |

|

| Intervention by Franco Mazzucchelli at Volterra ’73 |

|

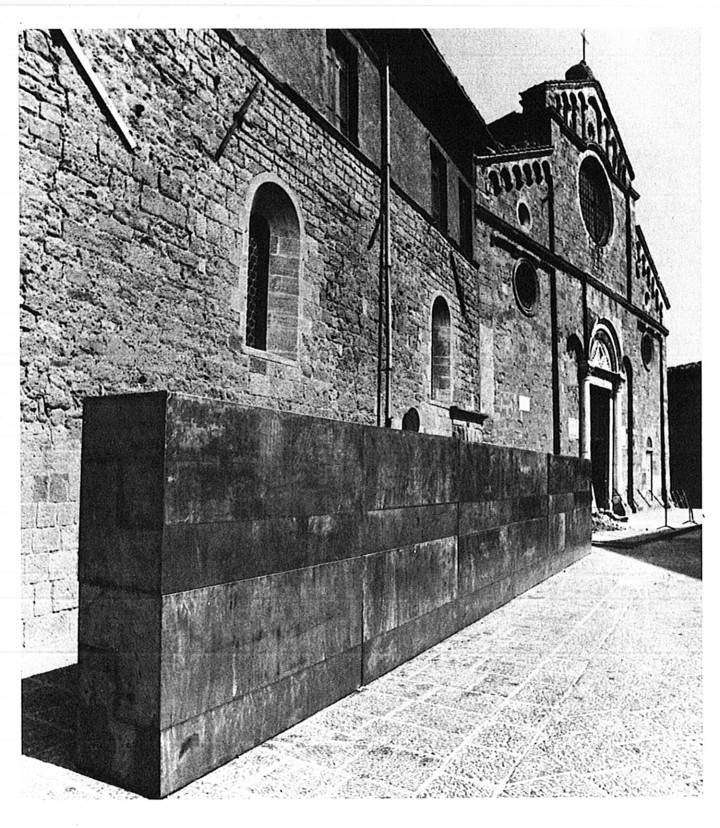

| Intervention by Nicola Carrino at Volterra ’73 |

In the fall of 1973, Pier Paolo Pasolini shot a documentary portraying the medieval village of Orte, at the invitation of a Rai television program known to involve intellectuals of all sorts to comment on one of their chosen works of art. Pasolini chose not to choose: with unfailing acuity, he proposed The Shape of the City, focusing attention not on a particular object-work but on the empirical matter of the community, synthesized perfectly in the urban dimension, realizing how this fabric had to be defended “with the same doggedness with the same good will, with the same rigor with which one defends a work of art by a great author.” Wrote Henri Lefebvre, “The urban? It is a general form: that of assemblage, that of simultaneity, that of spatiotemporal in societies, a form that is affirmed on all sides throughout history, whatever the vicissitudes of this history. From the origins and birth of societies onward, this form is confirmed as a form right up to the explosion we are witnessing.”

The problem moved by Pasolini is the same one addressed by Crispolti pioneeringly in Volterra 73 and in a more mature form in the XXXVII Venice Art Biennale in 1976 with the famous exhibition for the Italian Pavilion L’ambiente come sociale. Indi the issue was to promote a season of cultural engagement, without deconstructing the traditional apparatus but rather engaging and integrating it into a contemporary language enriched by the use of new media. Documentation and video espoused the same cause as sculpture and painting, in a modus operandi involving direct interaction with the public, for a new existential consciousness.

|

| The Gori Collection in the Fattoria di Celle (work by Alberto Burri). Photo Visit Tuscany |

If Crispolti was undoubtedly the forerunner of an etymological and programmatic coinage of Environmental Art addressed to the public apparatus, one must count the alternative parallel of the Fattoria di Celle in Santomato, in the province of Pistoia. As early as 1970, collector Giuliano Gori set up the grounds of his villa at Celle with the specific intention of bringing to life a large-scale collection of monumental settings and sculptures with an environmental character, rigorously moderated on criteria preserving both the surrounding nature and the Romantic precontext grafted on in 1840 by Pistoia architect Giovanni Gambini: Launched in 1982, the Gori Collection in the Fattoria di Celle is still one of the most internationally known examples of Environmental Art, benefiting the uniqueness of the patron’s taste, a quality indulgent in shaping the immanent character of the works present (with signatures ranging from Mauro Staccioli to Robert Morris to Dani Karavan to Daniel Buren), which not only distance themselves from the ephemeral tone of other environmental proposals, rather evolve over time by integrating organically with the vegetative cadence of the land.

This example, in addition to Crispoltian theoretical innovations, perfectly summarizes how much Environmental Art fostered the process from aesthetics to ethics: as the postmodern era progressed, the work of art matured in meaning in its social spillover, or relationality,“from the processes that preceded it to those that are produced as a result of its existence.” Art-related environmentalist and ecosophical considerations take a decidedly topical turn, targeting the burning issues of anthropocentric climate change. As proof of how far-sighted Volterra 73 has been in this ethical (and even aesthetic, just think of the 2015 reenactment, again in Volterra, again under the curatorship of Enrico Crispolti) sense, it is decisive to propose a hermeneutics of the contemporary as a response to this environmental quest. Hermeneutics, meaning translation, interpretation, that communicative effort preparatory to universal understanding and awareness of common roots. Art as environment translates "living."

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.