Art and sport. Fencing according to Arturo Rietti

Long is the list of artists who, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, at the dawn of modern sports, began to take an interest in a wide variety of sports, to the point of becoming athletes themselves: Gustave Caillebotte in his spare time devoted himself to rowing and sailing; Paul Signac also indulged in the latter activity, traveling the Mediterranean in his boat; Maurice de Vlaminck as a young man was a good cyclist; and in some cases artists practiced both creative activity and professional sports at the same time (this is the case, for example, of the Portuguese Francisco dos Santos, who was a sculptor but also a midfielder for Sporting Lisbon). There is, however, a substantial difference that separates sports that began to spread in those years, such as soccer and cycling, and that managed to gain cross-popularity, from a practice such as fencing. Fencing is inescapably linked to its past as a military and chivalric art, and experiences a present in which it treads the blurry line between sporting activity and method for settling disputes: past the First World War, duels of honor stubbornly continue to survive, but it is possible to say that, from 1918 onward, fencing becomes, as master Davide Lazzaroni puts it, “more and more a sporting practice, formative on a psychophysical level and untethered from bloody objectives,” and that young fencers become “more and more sportsmen trained in the goal of medal achievement and less and less in having to save their skins in a duel.” It is in this context that the story of Arturo Rietti (Trieste, 1863 - Fontaniva, 1943), a painter linked to the realism of Nikolaos Gysis and partly to the painting of the Macchiaioli but also to the Lombard scapigliatura, an excellent portraitist, and a valiant fencer, takes place.

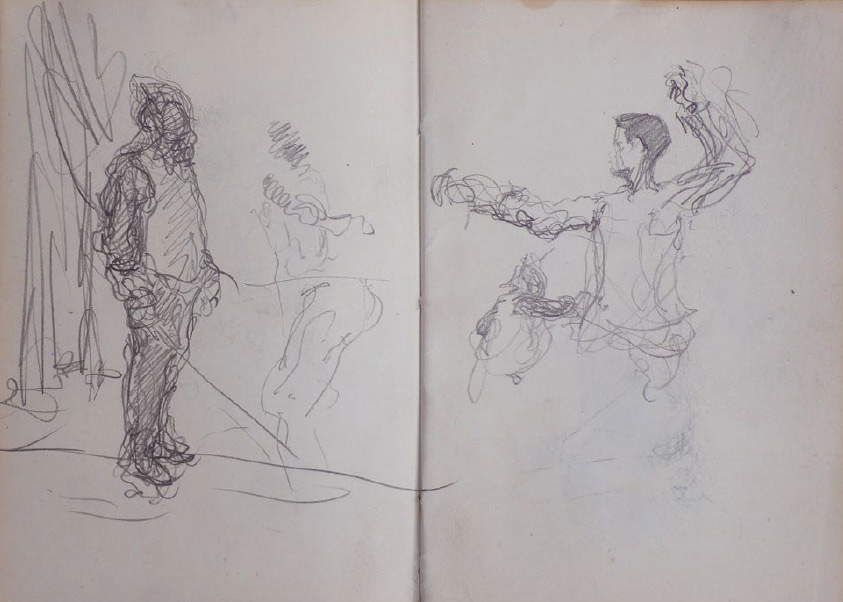

Rietti began fencing at a young age. We know that he also dabbled with arms in Munich, where he was a student at the local Academy of Fine Arts (it was at this juncture that he met Gysis, who became his teacher): as a Triestine from a wealthy family and a citizen of the Habsburg empire, though a proud irredentist, the artist knew German well and was a participant in the multicultural climate that was alive in turn-of-the-century Trieste. Having finished his academic studies, Rietti did not abandon the fencing environment, and in the city to which he moved in 1886, namely Milan, he began to frequent the Società del Giardino, an exclusive club founded in 1783, which in 1882 opened its own fencing hall (still active today: it is one of the most titled societies in Italy and every year organizes a tournament in the sumptuous clubhouse). Indeed: we could say that fencing makes it easier for the artist to obtain the commissions he would soon begin to receive from high society. Milan guaranteed good economic income for the young painter (although they would become stable only at the beginning of the twentieth century), who did not, however, renounce frequent visits to his hometown: it was precisely in Trieste that he met Count Francesco Sordina, of whom he executed, in 1896, a “Ritratto in assetto da scherma,” which he exhibited at the Circolo Artistico in the Julian city and whose current location we do not know. We do know, however, that fellow citizens liked Rietti’s work (who, in addition to the portrait of the count, exhibited six other paintings), and given the success he found in the world of fencing, it is possible to establish precisely at the year 1896 the beginning of the production of a good number of portraits of fencing masters, athletes and, more generally, works on the theme of fencing. A theme present, however, in the artist’s notes since his youthful years: in the recent monograph edited by Maurizio Lorber, a number of sheets have been published that testify how the interest in fencing is a constant in Rietti’s art. The painter had developed a particular graphic technique, which consisted of filling the sheets with thick curved marks with a flickering appearance, almost a tangle of apparent scribbles that actually reveal attention to movement, postures, and expressions. We see this well in a couple of these sheets, where we observe what appears to be a master, posed, his weapon pointed toward the ground, apparently explaining the lesson to his pupils. In addition to his figure we see another, barely sketched, of the torso and back leg of an athlete, and a third: a fencer on guard, with his armed arm outstretched and his unarmed arm bent upward, as was the custom at the time.

|

| Arturo Rietti, Fencers from a Notebook (1886-1887; drawing on paper; Trieste, Rietti Heirs Archive) |

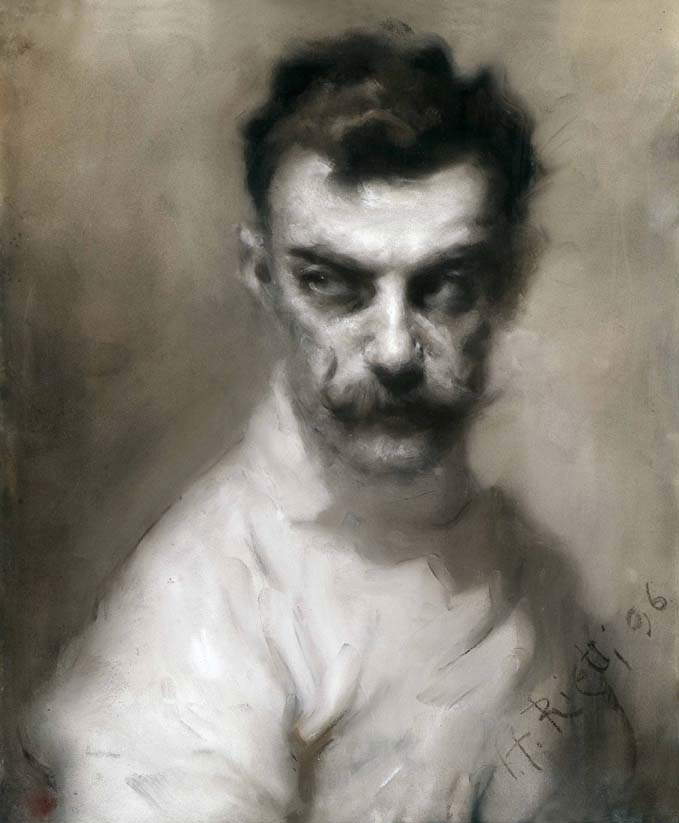

One of the earliest portraits that Rietti executed is that of the Friulian master Luigi Barbasetti (Cividale del Friuli, 1859 - Verona, 1948), now kept at the Revoltella Museum in Trieste, which moreover houses a conspicuous nucleus of Rietti’s works, devoted to fencing and beyond. Barbasetti was one of the most exalted masters of his time: during the period in which Rietti portrays him he taught his art in Trieste, but already in those years (in 1894 to be exact) he received a call from the Archduke of Austria Francis Savior of Habsburg-Tuscany, who wanted him in Vienna to update the local school. Barbasetti immediately moved to the capital of the empire, where he founded a fencing school that would be enormously successful in spreading his method throughout Austria and Hungary. The Friulian master specialized in saber: if the Hungarian fencing school soon became one of the strongest in the world (and the tradition of Magyar fencing continues to this day), much of the credit goes to Barbasetti himself. Rietti depicts him in one of his most intense portraits. The face is slightly downcast, typical of the fencer about to don the mask. The gaze, however, is fiercely turned in front of him: it does not meet the gaze of the observer, but seems almost to scrutinize an opponent with an air of defiance and, at the same time, communicates great confidence and awareness of his own means. Rietti thinks that “if the portrait does not reveal a secret, deep truth of the subject’s soul, it is not poetry.” Few portraits (and not only in his production) are as poetic and strong as that of master Luigi Barbasetti. The choice of color (only black and white) and the technique used (pastel, which suggests the impression that the master’s figure stands out against a curtain of smoke, and which contributes to the vividness of his expression) are functional to best achieve the final result: an expressive portrait that captures deep down “the soul of the subject.”

|

| Arturo Rietti, Portrait of Master Luigi Barbasetti (1896; pastel on cardboard, 51 x 42 cm; Trieste, Museo Revoltella) |

|

| Arturo Rietti’s paintings of fencing at the Revoltella Museum in Trieste. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

If Barbasetti is one of the best masters of northern Italy, one of the greatest interpreters of fencing of the Neapolitan school of the time is instead Carlo De Palma, who between 1906 and 1910 taught at the Società Ginnastica Triestina (the fencing club where Arturo Rietti trained), and who years later would train one of the greatest champions of the specialty, winning two Olympic medals: Irene Camber. The painting depicting the Naples-born master is an oil on canvas, dating from 1908, which has different assumptions than Luigi Barbasetti’s portrait. Rietti succeeds in giving considerable plastic relief to the figure of Carlo De Palma through the use of strong chiaroscuro contrasts, which also enhance the artist’s ability to probe, through his keen sense for psychological introspection, the character of the subject. The sense of defiance derived from Luigi Barbasetti’s portrait (his stance seemed almost to affirm his being a fencer even before being a master) is here replaced by pride in his role, which is expressed in the form of a haughty pose: hands resting on his hips, uniform neatly buttoned, gaze fixed and imperturbable. The figure emerges from a dark background: a peculiarity that has become characteristic of Rietti’s art, through which seems to be reflected, as the aforementioned Lorber has written, “the character of the artist, introverted and shadowy, who yearns to sublimate himself in his peculiar stylistic figure.”

|

| Arturo Rietti, Portrait of Master Carlo De Palma (1908; oil on canvas, 86 x 70 cm; Trieste, Museo Revoltella) |

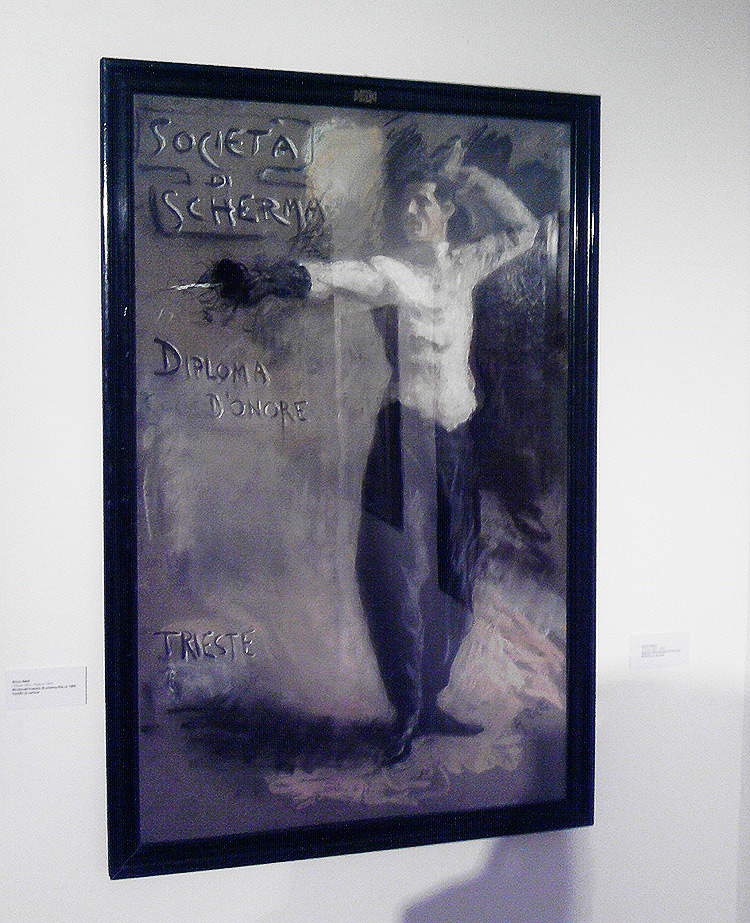

The Triestine artist’s activity is not confined, in the field of fencing, to portraits of masters. In fact, the painter ventured into the production of diplomas for fencing societies. One of these is preserved in the Revoltella Museum: in the work, probably dating from 1909 (to this year refers a letter from Count Sordina, who requests the diploma from the painter, and in the nobleman’s collection it will remain until it is donated to the Trieste museum), a fencer with a longilinear physique, elegant in his white uniform with black pants and glove, is about to take up a guard position silhouetted against an undefined background, shaded in pastel, the colors of which echo those used for the fencer, with a chromatic range that, again, is particularly reduced to achieve an effect of immediacy as well as greater refinement. We have reports that Rietti was often invited to Vienna and Budapest, the two major centers of the empire, on the occasion of important fencing tournaments for which the artist was called upon to make, precisely, diplomas of honor.

|

| Arturo Rietti, Diploma for Fencing Society (c. 1909; pastel on cardboard, 98 x 62 cm; Trieste, Museo Revoltella) |

Fencing would continue to be, for almost all of Arturo Rietti’s life, not only a way to create a good network of contacts that would allow him to work (many of his assignments, as anticipated, would come to him from well-known figures in the fencing milieu), but also an art to which the artist would always be intimately attached and of which he would continue to remember even when his strength began to fail. In his monograph, Lorber quotes a passage from Rietti’s notes, dated January 20, 1943 (two weeks before his death). In an Italy ravaged by war and twenty years of fascism (towards which Rietti would always, and publicly, declare his utter aversion, eventually subjecting himself to enormous risks), the painter, by now tired and disillusioned, is reminded, as in a dream, of a duel, probably for reasons of honor, against a professor in Venice, which ended successfully for the artist: “When the scene at the Caffè Filodrammatico? My slaps at prof. Ara? Challenge. Trip to Venice, dinner with Pallich and Stuparich at the Quadri, duel (naked torso, great cold in the bomb room, campo la Fenice) cut off Ara’s nose, my little wounds, breakfast at the Cavalletto, I think.”

Reference bibliography

- Luca Caburlotto, Enrico Lecchese (eds.), Arturo Rietti (1863-1943) and his time, conference proceedings (Trieste, October 17-18, 2013), Arte Ricerca & Circolo Artistico di Trieste , 2013

- Davide Lazzaroni, The fencing master: the evolution of a profession .

- Past, present and future prospects, Master’s thesis National Fencing Academy, 2013

- Maurizio Lorber, Arturo Rietti, CRTrieste Foundation, 2008

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.