Art and sport. Athletics according to Robert Delaunay

The eighth Olympic Games were held in 1924 in Paris. Theathletics program, what is now known as the “queen” discipline of the Olympics, is held July 6-13, at the Stade Olympique in Colombes, a suburb of the French capital not far from Argenteuil. The competitions, reserved for male athletes only, are dominated by Americans and Finns, but there are brilliant exceptions, such as that of Britain’s Harold Abrahams, who surprisingly wins the 100-meter race, or Scotland’s Eric Liddell who, as a fervent Christian, skips just the 100 meters as the race is run on a Sunday, but makes up for it by winning the 400 (the story of the two Britons will inspire the film Moments of Glory), and again the Italian Ugo Frigerio, the only champion of the 1920 Olympics to confirm his title (in his case, in the 10.000 meters), or Australia’s Nick Winter, who set the triple jump world record. Attending the competitions, in the audience, is a very special spectator, who is very strongly affected by the fascination of athletics: he is the artist Robert Delaunay (Paris, 1885 - Montpellier, 1941).

For some years now, Delaunay has been offering a suggestive reinterpretation of Cubism: the French artist starts from fragmentation, geometric decomposition and analysis of objects observed from all angles and points of view, as Picasso, Braque and colleagues did, but he prefers to focus on color, which was not decisive for the purposes of Cubist poetics (indeed: for many years color lost importance in the eyes of the Cubist painters, who in several works simply used grays and browns). Delaunay, on the contrary, is enthusiastic about the expressive use of color that he sees in the works of the Fauves, and he shows enormous appreciation for the work of Seurat and Signac, who based their art on a scientific approach to color: consequently, Delaunay’s painting also finds its raison d’être in the study of the relationships between light and color. For Delaunay, chromatic tones are like the harmony of music: his is therefore an attempt to bring, in painting, the qualities of music. This is noticed by a great poet, Guillaume Apollinaire, who, observing the work of an artist moved by the same convictions as Delaunay, the Czech Frantiek Kupka, coined the term"orphism": just as the mythical cantor Orpheus beguiled the beasts through the sweetness of his song, so Orphic painting aims to attenuate, with its lyricism and suavity, the rigorous severity of Cubism (so much so that it is also called"Orphic Cubism"). Delaunay began his research in the 1910s: after a brief interlude in Spain to escape the consequences of World War I, the artist returned to Paris in 1921.

The athletic competitions of the Olympics offered Delaunay the cue for a series of paintings that the artist made between 1924 and 1926, and which represented a first for his art: this was the series of Runners(Les coureurs). Eight paintings (to which one will be added in 1930) depicting athletes competing in a running race. This is not only new for Delaunay’s art: it is new for art in general. In fact, the French artist has a goal: to seek a theme that can fit the contemporary. Cubists like Picasso and Braque, in fact, had almost always focused on classical themes: still lifes, landscapes, musicians, portraits. For Delaunay, a new artistic language must also have a new theme: therefore, what better metaphor for modernity than sports, an activity that began to be structured and organized at the very beginning of the twentieth century, that drew thousands of people to stadiums, that thrilled people from all over the world, that could be easily understood by anyone?

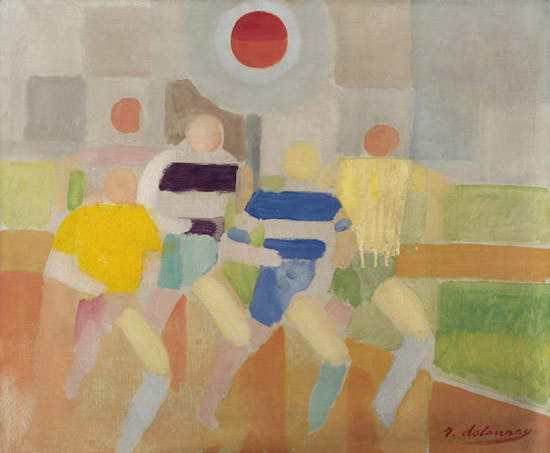

One of the earliest paintings, made in 1924, is now in the Musée d’Art Moderne in Troyes. It is a strikingly realistic painting: after this work, others followed that instead sought to reduce the figures of the runners to more essential forms. Using bright colors typical of Delaunay’s palette, the artist constructs the shapes of a group of five athletes competing for victory on the orange track of a stadium. The typically cubist geometric decomposition is still one of the foundations of Delaunay’s art, but with its iridescent colors (the jerseys of the runners are all painted in different tones of the three primary colors), the curved lines of the track and, by contrast, the horizontal blocks of the grandstands, it imparts a strong dynamism to the painting. The sense of movement is, after all, constant in Delaunay’s art. A further device that Delaunay adopted for his runners contributes to the latter: if we look at their figures, we can see that their feet are missing altogether. It is a bit as if Delaunay had taken a snapshot of the runners, come move: feet being the element of the body that the runners move the most, the result is that we do not see them well, just as we cannot distinguish the features of the faces, precisely because by catching the athletes in the moment, and in motion, we would not be able to distinguish them individually except for the most distinctive element, namely the color of the shirts (and also because Delaunay, like many other artists of the time who take on the theme of sports, is not interested in celebrating the individual champion or the individual athlete). It is a composition strongly based on rhythm, with horizontal and vertical lines that help to suggest the speed of the action (note how the grandstands were meticulously divided into three sectors through vertical lines that then follow in the lower part of the work, dividing even the runners into three different groups) strongly conveying to us all the innovative charge of Delaunay’s art.

|

| Robert Delaunay, Runners (1924; oil on canvas, 114 x 146 cm; Troyes, Musée d’Art Moderne de Troyes) |

As anticipated, the later works would know a greater degree of abstraction: these realizations are anticipated by a watercolor drawing, currently kept at the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Dijon and dating from 1924, in which runners are represented through elementary forms. Solid circles for heads and rectangles for striped jerseys are enough to convey to us the idea of athletes running on the track: similarly, in the background, black rectangles suggest that behind them are the bleachers of the grandstands. This is what happens in a work on canvas passed at auction by Bonhams in 2015: the greater degree of abstraction compared to Troyes’ Runners is evident from the fact that, to construct the athletes’ figures, Delaunay used, just as in Dijon’s watercolor drawing, pure forms (although, compared to the drawing, the degree of finesse is obviously greater and the runners are more easily distinguishable). A novelty compared to the Troyes painting, which was already hinted at in the Dijon drawing (and which appears here instead as the absolute protagonist) is the presence of the solar disk in the sky above the runners. This is an important presence because it recalls a work made about ten years earlier, known as Le Premier Disque (“The First Disc”). It is a painting that is fundamental to understanding Delaunay’s art: the artist juxtaposes, in quadrants arranged on concentric circles to form, precisely, a disk, different colors to create effects of light and movement, as the perception of a color changes depending on the colors it has nearby. This is how the writer Blaise Cendrars had expressed himself on this subject, “A color is not such in itself. It is a color insofar as it is placed in contrast with other colors. A blue becomes blue only when placed in contrast with a red, a green, an orange, a gray and all other colors.” And Delaunay himself says that on the basis of their “qualitative relations,” colors “are recreated by the eye of the observer in such a way that they gain vigor or are crushed by one another.” We see how Delaunay tries out various juxtapositions: complementary colors (the red-green and blue-orange sectors), primary colors (such as the blue and red in the center), various shades of the same colors, colors that blend through gradations (such as the yellow in the upper right quadrant that turns orange while also giving a sense of movement to the disc and breaking the strict horizontality). The purpose, as mentioned, is to test how the eye perceives the proximities of the various colors, what sensations it feels, whether the colors enhance each other or turn off, whether the observer is bothered by the proximity of two colors or whether on the contrary a relationship is pleasing to the eye.

|

| Robert Delaunay, Corridors (1924; watercolor drawing on paper, 25 x 33 cm; Dijon, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Dijon) |

|

| Robert Delaunay, Runners (1924; oil on canvas, 45.8 x 55 cm; private collection) |

|

| Robert Delaunay, Le Premier Disque (1912; oil on canvas, 134 cm diameter; private collection) |

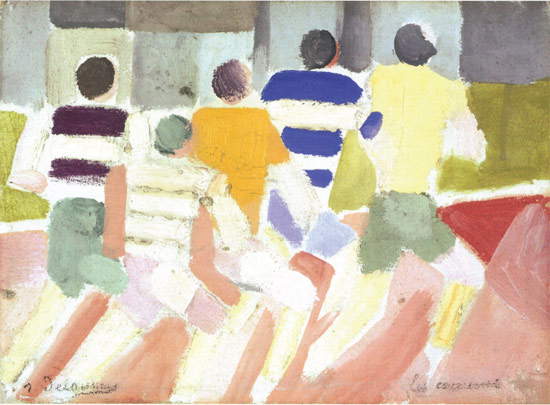

The juxtapositions between complementary and primary colors are obviously present in the Runners as well: we see this well in the painting preserved at the Staatsgalerie in Stuttgart (which, moreover, introduces a variant: the athletes are seen from behind and running to the right), where the yellow of the jersey of the central runner is contrasted with the blue of the one running next to him, and where the red of the track is placed side by side with the green of the lawn of the athletic stadium.

|

| Robert Delaunay, Runners (1924-1926; oil on canvas, 24 x 33 cm; Stuttgart, Staatsgalerie) |

There is, finally, one last interesting aspect of the Runners series: in addition to bringing together many of the fundamental characteristics of Robert Delaunay’s art, the Runners, on the one hand, bear witness to the fact that sport, in the 1920s, experienced a wide diffusion, coming to fascinate artists and literati, and on the other hand, they embody theuniversality of sport, the very essence of sporting practice. As mentioned above, Delaunay (as well as many of his contemporaries) is not interested in celebrating the individual athlete (yet, he would have stories to tell!). His runners do not have recognizable traits, they are not individually connoted: they are simply athletes running, struggling, sweating, giving their best in view of the final finish line. More gimmicks to communicate to us all the evocative charm of the sport.

Reference bibliography

- Impressionist and modern art, dasta catalog (London, Bonhams, June 24, 2015), Bonhams, 2015

- Gordon Hughes, Resisting Abstraction: Robert Delaunay and Vision in the Face of Modernism, University of Chicago Press, 2014

- Michel Hoog (ed.), Robert Delaunay (1885-1941), exhibition catalog (Paris, Orangerie des Tuileries, May 25-August 30, 1976), Editions des Musées Nationaux, 1976

- Serge Lemoine (ed.), Donation Granville : Musée des Beaux-Arts de Dijon : catalogue des peintures, dessins, estampes et sculptures : Oeuvres réalisées après 1900, Ville de Dijon, 1976

- Bernard Dorival, Robert Delaunay, 1885-1941, Jacques Damase Editions, 1975

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.