Antonio Canova and Napoleon: the complicated story of a bust-portrait

October 5, 1802: After a two-week journey departing from Rome, Antonio Canova (Possagno, 1757 Venice, 1822) finally arrives in Paris. He was given a prestigious commission: he was to be in charge of sculpting the portrait bust of Napoleon Bonaparte (Ajaccio, 1769 St. Helena Island, 1821). The invitation came directly to him from the then first consul of France (he would be proclaimed emperor of the French just two years later) in September: acting as intermediary is François Cacault, French ambassador to the Papal States. Canova, at first, is not enthusiastic about the opportunity: at the time of the French occupation in Italy he had been very critical of the future emperor. Not least because the sculptor himself had suffered the repercussions of the political instability of the time: he had had to leave Rome to return to his native Possagno, and in addition he had had his artist’s annuity, which he received from the now fallen Republic of Venice, suspended. And despite the promises of Napoleon, who had hinted in a letter dated August 6, 1797, that the entitlement would be restored to him (“Artiste célèbre, vous avez un droit particulier à la protection de l’armée d’Italie. Je viens de donner l’ordre que votre pension vous soit exactement payée et je vous prie de me faire savoir si cet ordre n’est point exécuté, et de croire au plaisir que j’ai de faire quelque chose qui vous soit utile,” “Famous artist, you have a particular right to protection from the army of Italy. I have just given orders that your pension be exactly paid to you, and I beg you to let me know if this order is not carried out, and to believe that I will have the pleasure of doing anything that may be useful to you.”), Canova, who, moreover, made use of the annuity mainly to help needy artists, would no longer enjoy his pension. Venice, in fact, following the Treaty of Campoformio, had been ceded to Austria by Napoleon, and Austrian Emperor Francis II had required the artist, as a condition for getting his pension back, to stay in Venice for at least six months a year. But Canova had refused.

Moreover, the artist did not forgive Napoleon for the offense to his native land, which had been treated as a mere bargaining chip at the end of the first Italian campaign. Already during the war years he had written, on April 20, 1797, a letter to his friend Giannantonio Selva, expressing his concern: “I would be quite happy to willingly lose anything, indeed life itself, as long as I could in such a way benefit my adorable homeland, which such I will call it as long as I have a shadow of breath left.” And of course his thoughts would not change five years later. Still, Canova also showed hostility toward Napoleon for the havoc wrought on the works of art taken from the occupied territories and sent to France: from the very first requisitions, according to his biographers, he had expressed deep regret for the spoliations. Canova had therefore first refused the invitation, citing a number of excuses to Cacault: commitments, health reasons, the difficulties of the trip. However, the new pope, Pius VII, who ascended to the papal throne in 1800, feared that the refusal of his greatest artist risked souring diplomatic relations with France: an eventuality the pontiff wanted to avoid at all costs. It had therefore become necessary for him to intervene, as well as for the Vatican Secretary of State, Cardinal Ercole Consalvi, to convince the artist: the fear of repercussions if the invitation was declined was too great. So Canova, albeit reluctantly, had left Rome to travel to the French capital.

Arriving in Paris, the sculptor was housed in the palace of the papal legate Giovanni Battista Caprara Montecuccoli: shortly after his arrival, Napoleon’s secretary, Louis Bourienne, took him to the château de Saint-Cloud, at the time the residence of the first consul. It is here that Canova meets Napoleon, and it is here that the sittings will take place that will serve the artist to obtain the first clay model of the portrait. It would take five for Canova to obtain the first clay model, dated October 16. From this first sketch, Canova would then obtain the plaster that he would take with him to Rome in order to sculpt the marble. The plaster prototype is believed to be the one now in the Possagno Gipsoteca (there is also another, identical example in theAccademia di San Luca): Napoleon is portrayed in uniform, frontally, with his eyes hollowed but fixed and slightly turned downward as a sign of reflection and concentration, his eyebrows frowned to express the depth of the first consul’s thoughts and the high responsibility derived from them, his chin pronounced, his full face conveying all the firmness of character but also the freshness of his thirty-three years.

|

| Antonio Canova, Portrait of Napoleon Bonaparte (1802; plaster, 67 x 44 cm; Possagno, Museo Canova, Gipsoteca) |

During the sessions, the artist and the first consul of France got to converse with each other. Antonio D’Este, a student of Canova known for writing the master’s memoirs, has left us a veracious account of the meetings between Canova and Napoleon. Although relations between the two, however detached, had never transcended the plane of cordiality, the sculptor, D’Este recounts, had failed to keep to himself his thoughts about the spoliations and the end of the Venetian Republic. “He did not keep silent to the first consul that the papal palaces had been stripped by the enemies of the order, that the ancient monuments were abandoned to ruin, and everything presaged a dismal future, if the pontiff lacked the ways to prepare for it [...]. He bitterly grieved at the stripping done in Rome of the monuments of the Greek and Roman arts, a lament that was now made common to all Italians, and to the healthy part of the French [...]. Greater sorrow he felt for the transportation of the horses from Venice and the subversion of that ancient republic, telling the first consul, that those were things that would afflict him all the time of his life.” Nevertheless, Napoleon happily spent his sessions in the company of Canova. However, it would not be the one modeled in presentia that would be the portrait destined to be most successful among both contemporaries and posterity. In 1801, in fact, Canova had agreed to create, for the government of the Cisalpine Republic, a colossal statue that was to portray Napoleon himself: it is likely that the sculptor had accepted the commission, despite his aversion to Napoleon, because the first consul was to be effigyed in the guise of Mars the Peacemaker. The contract, however, would not be signed until January 1803: in the meantime, the artist had been able to use the portrait created in Paris to study the statue’s head.

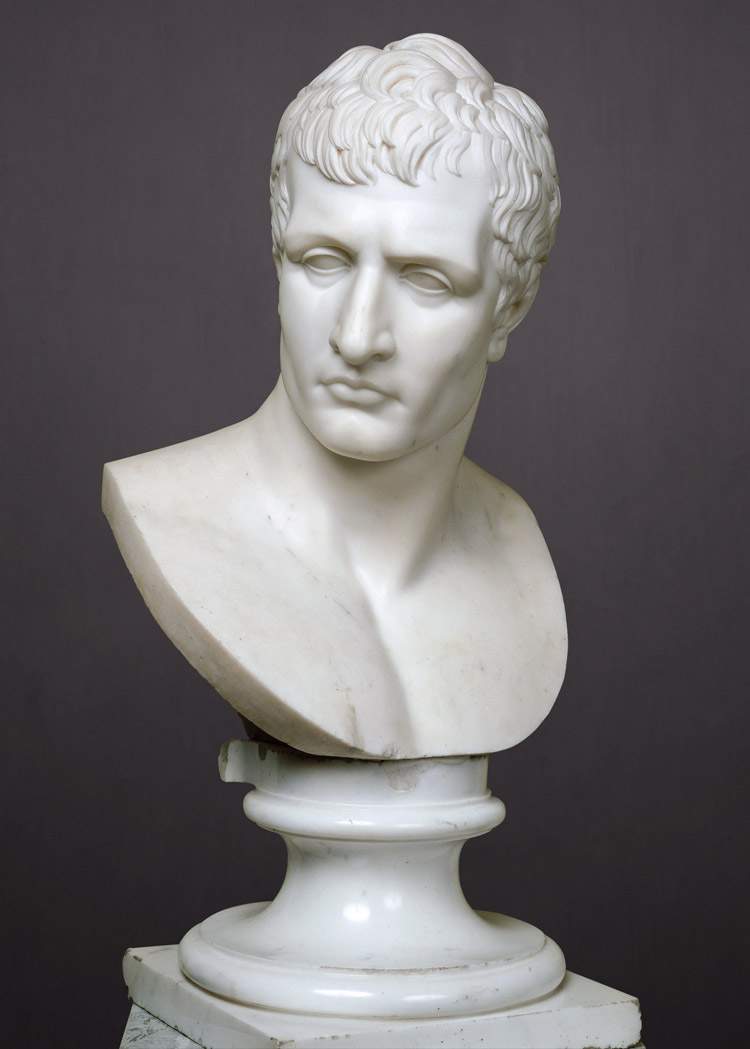

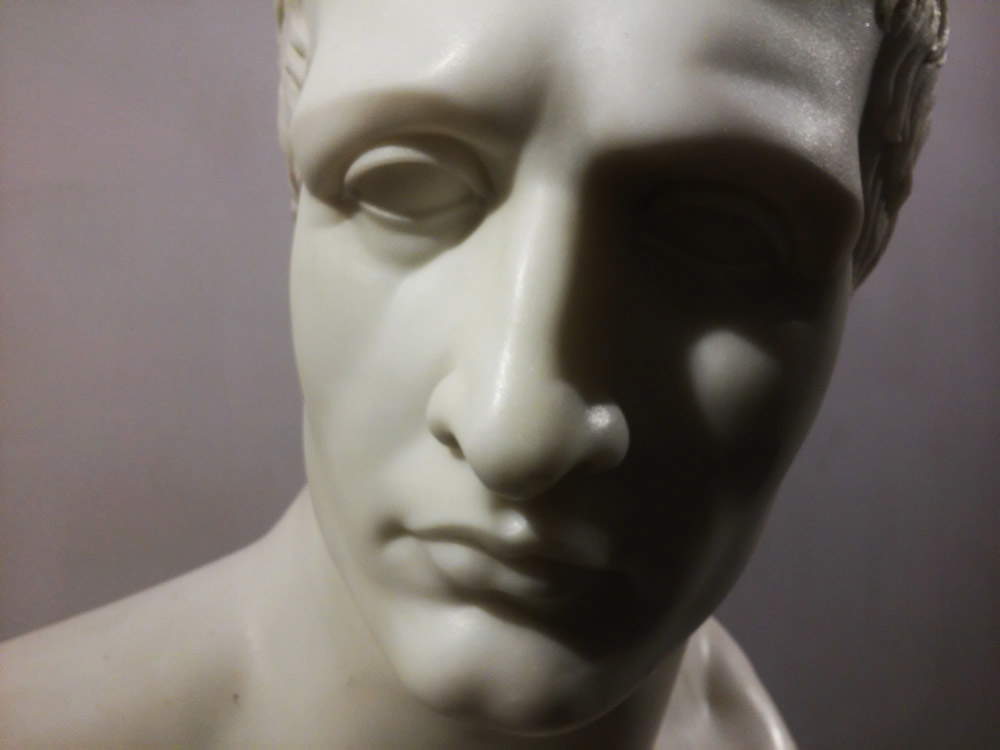

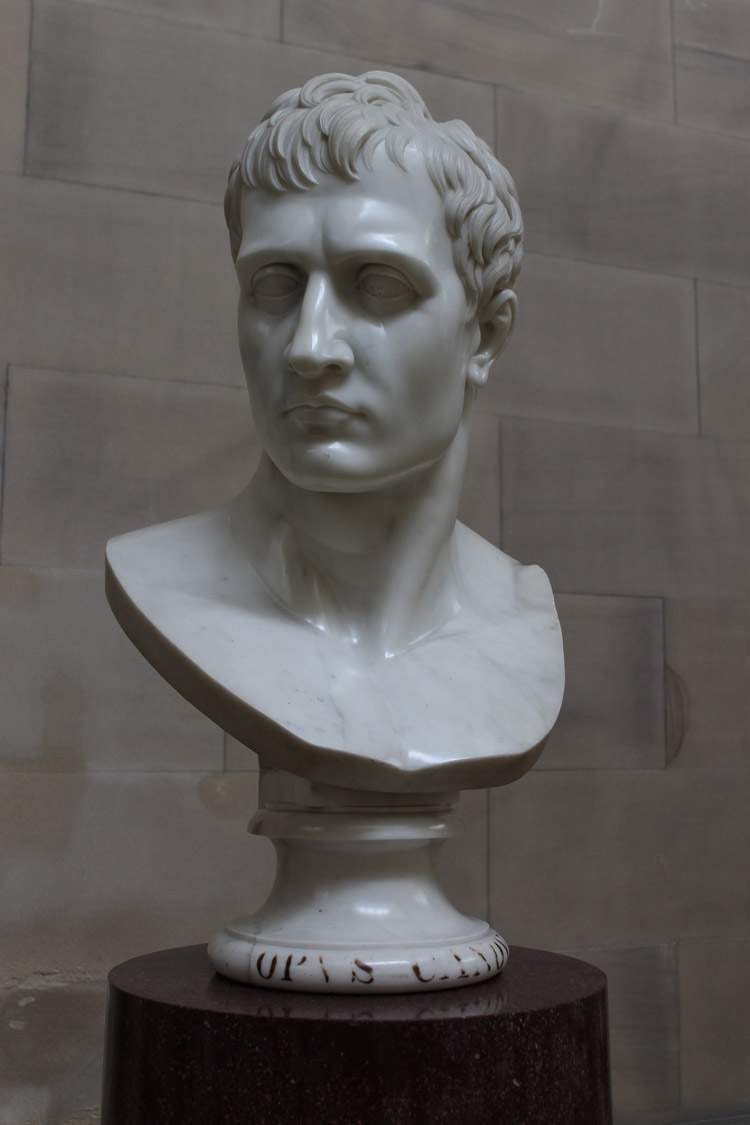

Canova literally “strips” the portrait of the first consul by removing the uniform and leaving him bare-breasted: the idea is to idealize Napoleon, to give the subject such a dimension as to place him outside of time. In addition, that twisting of the neck is introduced that gives a sense of natural movement to the head: enough to make the portrait much more alive than the one made in Paris. The resulting head is the one that would later be used for the great statue: surely we are no longer dealing with a truthful and natural Napoleon, but rather with a Napoleon who resembles a Roman emperor, an ideal portrait that is not intended to provide a truthful and realistic representation of the subject, but to emphasize his qualities and depth of character. It should also be added that Canova, according to biographers, believed that Napoleon had a physiognomy particularly suited for an old-fashioned portrait: his task was therefore made easier.

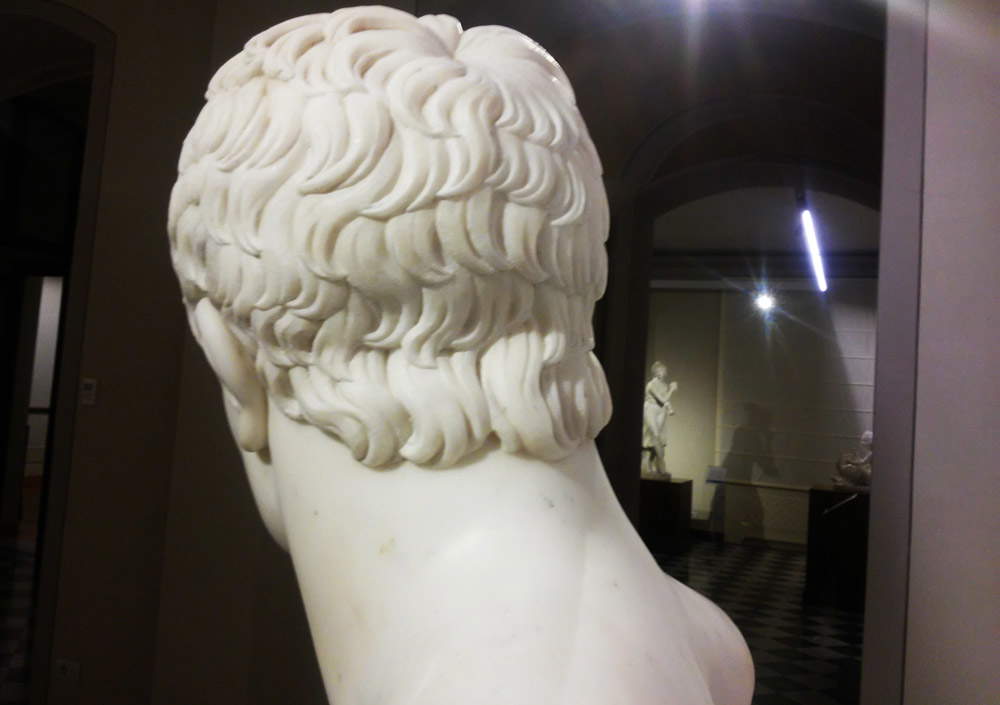

We continue to observe the portrait: the forehead is high, framed by strands of hair that fall over the face with calculated and mock unkemptness. The eyes remain hollow, but the gaze is now lost in the distance. The nose, large and pronounced, gives sign of the subject’s virility. The thin mouth shows no emotion. The hair, then, is a further distinguishing mark: Napoleon had in fact adopted the fashion, which spread after the French Revolution as a sign of discontinuity from the past, of short hair (“Caracalla style” or “Titus style,” it was said at the time), which also had an additional significance for him, because it also identified him aesthetically as the new Caesar. The end result is of a beauty that certainly did not belong to the real Napoleon, but it mattered little: the purpose of the portrait was to express a strong and convincing idea, and not to restore the true features of the first consul.

|

| Antonio Canova and workshop, Portrait of Napoleon Bonaparte (1803-1822?; marble, height 76 cm; St. Petersburg, Hermitage). All the details that follow belong to this work. |

|

| Antonio Canova and workshop, Portrait of Napoleon Bonaparte, Front view |

|

| Antonio Canova and workshop, Portrait of Napoleon Bonaparte, Right side view |

|

| Antonio Canova and workshop, Portrait of Napoleon Bonaparte, Left side view |

|

| Antonio Canova and workshop, Portrait of Napoleon Bonaparte, Detail of hair |

|

| Antonio Canova and workshop, Portrait of Napoleon Bonaparte, Close-up of the face |

|

| Antonio Canova and workshop, Portrait of Napoleon Bonaparte, Close-up of the face from the side |

|

| Antonio Canova and workshop, Portrait of Napoleon Bonaparte, Close-up of head |

|

| Antonio Canova and workshop, Portrait of Napoleon Bonaparte, exhibited at the exhibition After Canova. Paths of Sculpture in Florence and Rome (Carrara, Palazzo Cucchiari, 2017). |

This portrait was a remarkable success, so much so that even a critic who was always hard on Canova like Karl Fernow in 1806 praised the work, pointing to it as the best portrait of Napoleon: soon, Canova’s bust would become a kind of “official canon” for the representation of the first consul as well as future emperor. There are several specimens that remain of the portrait. The only one documented is the one that is now part of the Duke of Devonshire’s collections: after the artist’s death, the work, dated 1822, had remained in Canova’s studio, and the artist’s half-brother, Giovanni Battista Sartori, sold it to the Marchioness Anna of Aubercorn, who in turn gave it to the sixth Duke of Devonshire, who placed Canova’s work in the center of the sculpture gallery at the Chatsworth residence, opposite a bust of Alexander the Great. Another well-known example is the one in the Pitti Palace in Florence, among the few to be believed to be by the sculptor’s hand. In fact, many of these busts were produced on a large scale, using methods that today we would call “industrial”: even, Napoleon’s sister, Elisa Bonaparte Baciocchi, who ruled Lucca, Carrara and Tuscany, founded a factory in the city of marble that had precisely the task of mass-producing specimens of the portraits of Napoleon and his family. Again, those instead created by the sculptor’s hand might include the bust now housed in theHermitage in St. Petersburg, in Italy in 2017 for the exhibition Dopo Canova. Paths of Sculpture in Florence and Rome (Carrara, Palazzo Cucchiari). A rather difficult sculpture: undocumented, of therefore arduous dating, it was excluded from the Canova catalog by Giuseppe Pavanello, who suggested in his 1976 monograph that it should not be considered an original. The work entered the Hermitage in the second half of the 19th century, was first located in the TavriÄeskij Palace (at that time one of the residences of the Russian imperial family), and since it is in any case a work of the highest quality and has been attested in St. Petersburg since 1825, scholar Sergei Androsov considered it to be a work made directly by the artist, albeit with the help of his workshop.

It was said that the bust was a great success: many of Canova’s contemporaries praised the portrait of Napoleon. It is therefore worth concluding by quoting the testimony of the Danish poetess Frederica Brun, a friend of the Venetian sculptor, who spoke of the work in these terms: “I often went to his studij alone, or in company with some artist among my friends in Rome. We freely spoke our opinion of the works that stood before us, and I almost blissed myself among so many the so diverse works. Thus I saw with deep admiration the first bust of Napoleon, then first consul, which seemed to me equal to any ancient work. I esteemed it a head of work for ispeciality of expression, physiognomy, and art of modeling.”

Reference Bibliography

- Sergej Androsov, Massimo Bertozzi, Ettore Spalletti, After Canova. Paths of Sculpture in Florence and Rome, exhibition catalog (Carrara, Palazzo Cucchiari, July 8-October 22, 2017), Fondazione Giorgio Conti, 2017

- Massimiliano Pavan, Writings on Canova and Neoclassicism, Quaderni del Centro Studi Canoviani, 2004

- Hugh Honour, Paolo Mariuz, National edition of the works of Antonio Canova, Istituto Poligrafico e Zecca dello Stato, 1994

- Giuseppe Pavanello, Giandomenico Romanelli, Antonio Canova, exhibition catalog (Venice, Museo Correr and Possano, Gipsoteca, March 22-September 30, 1992), Marsilio, 1992

- Giambattista Vinco da Sesso, Antonio Canova: works in Possagno and the Veneto region, Tassotti, 1992

- Sergej Androsov (ed.), Canova at the Hermitage. Le sculture del museo di San Pietroburgo, exhibition catalog (Rome, Palazzo Ruspoli, December 12, 1991 - February 29, 1992), Marsilio, 1991

- Giuseppe Pavanello, The Complete Works of Canova, Rizzoli, 1976

|

| Antonio Canova and workshop, Portrait of Napoleon Bonaparte (1803-1806?; marble, height 65 cm; Chatsworth, Devonshire Collection). Credit |

|

| Antonio Canova and workshop, Portrait of Napoleon Bonaparte (1803-1822?; marble, height 77 cm; Florence, Palazzo Pitti, Galleria d’Arte Moderna) |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.