Andy Warhol: a critic or a celebrant of consumer society?

Everything has been written about Andy Warhol (1928 - 1987), but despite this, several questions still remain about many aspects of his art. There is one, in particular, that divides scholars dealing with his work: was Andy Warhol a disenchanted and disillusioned critic of the system and consumer society, or was he perfectly at home in the system and his pop art thus constitutes a kind of glorification of consumerism? Answering the question is not easy: we can therefore start from a statement by the artist. His book The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (From A to B & Back Again), published in 1975, contains a singular eulogy of Coca-Cola, which the artist celebrated in these terms: “If there is one great thing about America, it is that the tradition has begun here whereby the richest consumers buy essentially the same things as the poorest. You watch TV and you see Coca-Cola, and you know that the President drinks Coca-Cola, Liz Taylor drinks Coca-Cola, and you can think that you drink Coca-Cola too. A Coca-Cola is a Coca-Cola, and there is no amount of money that can guarantee that you will drink a better Coca-Cola than a bum on the street corner is drinking. All Cokes are the same and all Cokes are good. Liz Taylor knows it, the President knows it, the bum knows it, and so do you.”

|

| Andy Warhol, Green Coca-Cola Bottles (“Green Coke Bottles”); 1962; New York, Whitney Museum of American Art |

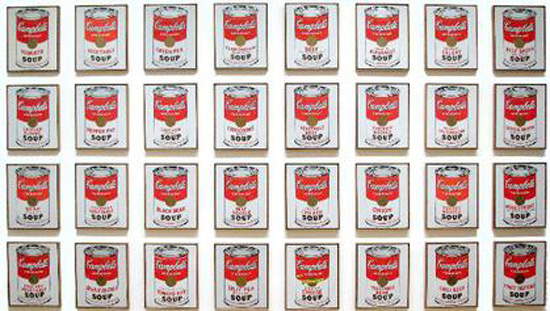

The message would therefore seem to be positive: true democracy would find fulfillment in the consumer society, which would make everyone equal before the characteristics of the most popular products. The most familiar, most mundane, everyday products, which everyone is able to obtain, thus become the most well-known specification of Andy Warhol’s art: we all have in mind the images of the same bottle of Coca-Cola or those of Campbell’s soup. Andy Warhol wished to draw the attention of observers to precisely these objects, so ordinary and commonplace that they even cause a stir. But precisely by virtue of its rise to the status of a work of art, the ordinary object takes on a strong symbolic charge, and it is on this symbolic charge that reflection must be conducted. Marcel Duchamp had also said this: “If you take the Campbell’s soup can and repeat it fifty times, what interests you is not the visual image. What you are interested in is the concept that led you to put fifty Campbell’s soup cans on the canvas.”

At a superficial analysis, the artistic representation of everyday objects, in Andy Warhol’s art, would seem to take the form of the natural consequence of their elevation as a symbol of the apparent democracy they have established. But in order to better frame the concept (to use the same term as Duchamp) that led Andy Warhol to depict the same image dozens of times, and to look more deeply into Warhol’s work, it is necessary to examine a very significant statement that the artist uttered during an interview for Art News magazine, in 1963. The interviewer, Gene Swanson, asked him for what reason he had begun to depict soup cans in his works. This was Warhol’s answer, “Because I used to consume it. I used to consume the same lunch every day, for twenty years, the same thing repeatedly. Someone told me that my life dominated me, and this idea appealed to me.” The habit of consuming the same products for days and years is characteristic of capitalist society, and for Warhol this habit had now become so repetitive that it came to dominate him: after all, we know that Warhol was fully integrated into the consumer society he represented on canvas. One U.S. art critic, Hal Foster, suggested that this integration of his into the consumer society was almost a kind of reaction: implicit in the phrase “my life dominated me, and this idea appealed to me” is, according to the critic, the consideration that if one cannot dominate a system from the outside, it is necessary to integrate oneself into that system, and thus to criticize it from within. This is another reason why Andy Warhol’s work appears to us so strongly ambiguous: because it is difficult to distinguish the blurred boundary between conformity and criticism.

|

| Andy Warhol, Campbell’s soup cans (“Campbell’s soup cans”); 1962; New York, Museum of Modern Art |

|

| Andy Warhol, Big torn Campbell’s soup can (“Big torn Campbell’s soup can”); 1962; Pittsburgh, The Andy Warhol Museum |

Warhol himself, who liked to move on the edge of this ambiguity, with his often contradictory statements about his art, does not help us understand what the real purpose of his art was. In what is considered one of his most important interviews, given to journalist Gretchen Berg in the summer of 1966 and later published under the title Andy Warhol: My true story, this is how he expressed himself about his art: “I think I represent the United States in my art, but I am not a critic of society: I simply paint certain objects in my paintings because they are the things I know best. I do not try to criticize the United States in any way, I do not intend to show any ugliness-I think I am just a pure artist. But I can’t say whether I really take myself seriously as an artist: I simply never thought about it.” In fact, Warhol never gave clear and definitive explanations of his work, and theirony that has always underpinned his art (and probably even his very existence) leads one not to attribute a literal meaning to his words, and to think that irony is Warhol’s preferred means of conducting his own critique of society: this is also why his art has divided the scholars who have dealt with it, between those who have seen Andy Warhol as an artist whose work did not aim at social ends, and those who have instead tried to give his art a deeper weight than the surface leads us to attribute to it. Campbell’s soup cans and Coca-Cola bottles thus offer a multitude of food for thought.

In these works, we might read the disenchantment of an artist who sees art now entirely subject to the laws of the market and therefore deprived of its intrinsic purity. We could glimpse the paradox whereby a dented soup can with a torn label, and therefore an object to be eliminated according to the logic of commerce, becomes on the contrary the most evident affirmation of individuality and freedom within a system based on conformism. We could also interpret them as an attempt to make art truly popular, since a subject familiar to everyone makes the work immediately recognizable: Andy Warhol, after all, began working as an illustrator for magazines with a large circulation, and he never hid the idea of wanting to vote for an art that could really reach everyone (and it is no coincidence that the name he chose for the studio he opened in 1962 was The Factory, “The Factory”). We could, in essence, say anything and everything about Andy Warhol’s art, and still fail to reach a firm conclusion. That the ultimate purpose of his art was precisely to lead us to discuss the very meaning of art in our time?

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.