Andrea Fontanari, the poetry of the everyday

From the window of Andrea Fontanari’s studio, one can see the gentle ridges that separate the Valsugana from the Adige Valley. In summer, the mountains of Trent are clothed in an emerald green that competes in intensity with the more ringing green of the grass of the valleys, under a sky tinged with a vivid blue, so far from that dusty, veiled celestial of the plain, so bright, sharp, as if purified. On the other side of the mountain is Trento, and on this side, below the slopes, lies the village of Pergine, which has none of the calm one imagines one would find in the mountains: it is a sort of continuation of the city, a bustling suburb stretching almost to the lake of Caldonazzo. It happens then that even the landscape that one admires from the window of Fontanari’s atelier contradicts itself, because below the slopes of the Marzola creeps the Valsugana state highway 47, a two-carriageway, four-lane snake that slithers toward the lake and then continues its course toward Padua: beyond the window glass, a viaduct saws the green and blue postcard of the valley in two halves. Outside, the soundtrack kindly provided by the Fersina stream, which flows just below the studio, is occasionally interrupted by other roars, those of the pressure washers of the neighboring wash, invested with the task of making presentable the buses that shuttle residents and tourists to the shores of the lake, to the streets of Trento, to the meadows of the Vigolana. It is in the midst of this verdant bustle that Andrea Fontanari’s works are born. Between the mountains and the traffic, between the city and the villages that dot the valleys, between the mountain pastures and the warehouses of the industrial zones. Attilio Bertolucci thought that painters, like poets, preserve in their work the traces of the bond that unites them to their lands, and sometimes these signs are more marked, sometimes they migrate to different altitudes, until they take on the transfigured contours of the idea. And if a glint of truth illuminates this impression, if it is really necessary to find the signs of a more or less unconscious fidelity, if it is licit to identify a possible convergence, an overlap between the memory of one’s own land and what one sees on a painted surface, then perhaps it is possible to find the reflection of this bond in Andrea Fontanari’s art as well. And so it is by looking around that it is possible to begin to survey his work.

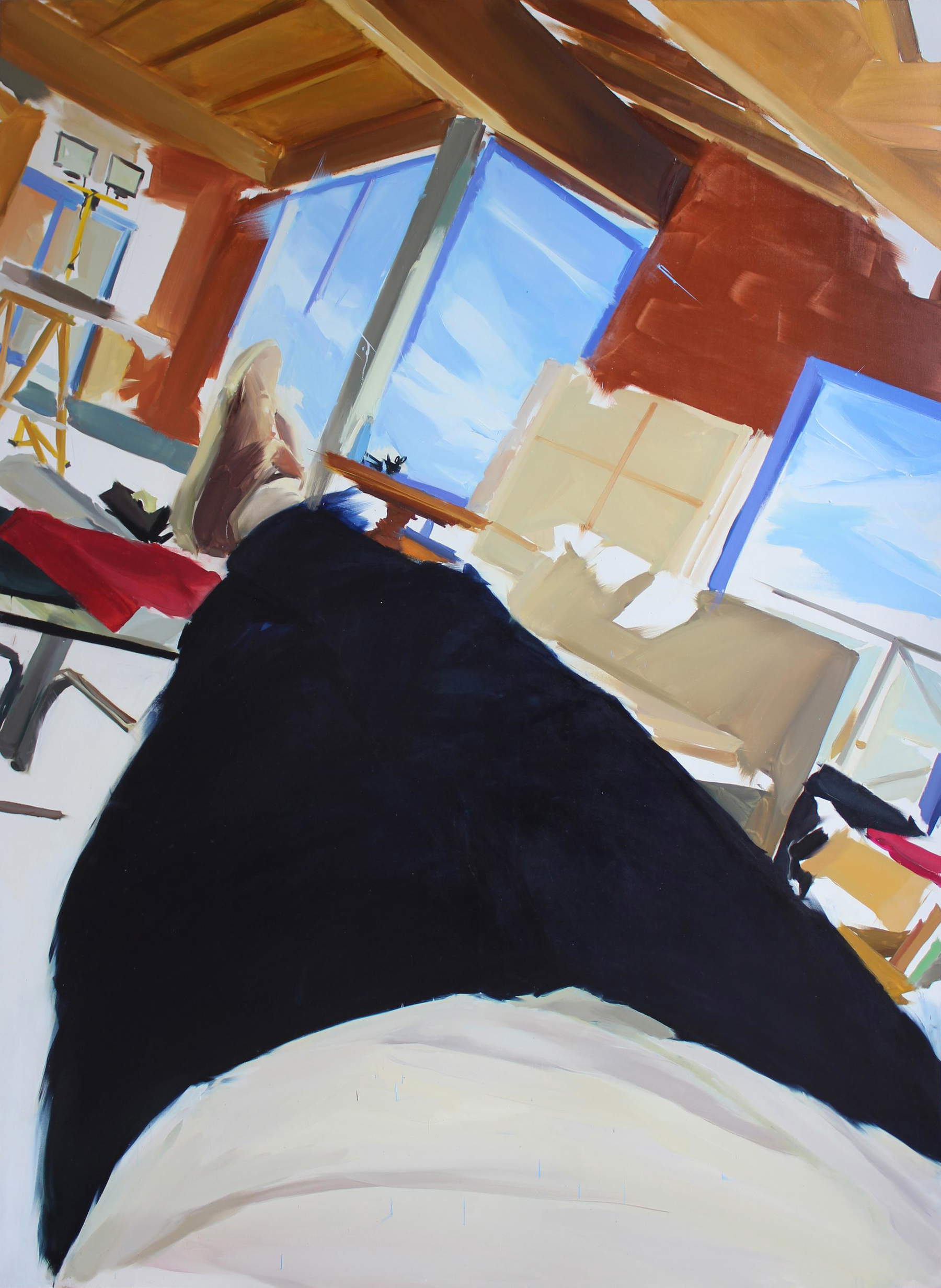

When one admires the works of Andrea Fontanari, whether contemplating the large formats or allowing oneself to be captivated by the smaller canvases, the temptation to recognize the light of Trentino in the summer in those colors so bright, so luminous, so saturated comes naturally. A festive, enveloping, if you will Mediterranean light. And zenithal: Fontanari’s scenes seem to be the continuous tale of a land where it is always noon. Merit also goes to his studio, a huge, sunburned open space , very hot in summer, with large windows facing the landscape. “Great exposure,” real estate agents would say. He also entered one of his paintings, the one that was exhibited at the end of 2023 at the exhibition on Italian painting at the Triennale in Milan: a singular self-portrait in which Fontanari’s face cannot be seen, a first-person account of a moment of rest in his studio. He is lying on the sofa, in the corner of the studio set up as a sitting room to receive guests. His legs raised and resting on the glass coffee table. In the background, the large windows through which the light from his paintings enters, open above slivers of blue. For the Romantic poets and painters, after all, the window was the symbol of the desire for infinity. Around it, the easels, the work tables, a few paintings packed to be sent to some exhibition. The oblique, photographic cut, the daring foreshortening, a lopsided undercutting that the artist from Trentino continues to practice with increasing insistence and that, with the bright colors, the liquid brushstroke and, most recently, a certain tendency toward abstraction, makes him recognizable even from miles away. Recognizability is the first proof of an artist’s personality, and Andrea Fontanari, it can be said without fear of contradiction, is among those rare young Italian artists who have been able to develop a recognizable figure since their twenties.

Of course, it was not a sudden achievement. A few years ago, at Artissima, two female visitors who were passing by the booth of Boccanera, Andrea Fontanari’s gallery, and had seen some of his works, were elated as they were convinced they had found a 20-year-old Italian who, they said, paints “paintings-beautiful-odd-looking-American pictures.” They evidently thought they were paying him a compliment (even though the artist was not there and could not hear), but the truth is that if you love an Italian artist, especially a young one, you must not, under any circumstances in the world, encourage him to be even more American, and consequently to loosen the ropes that keep him tied to tradition, to our art history. For that would be to condemn him to irrelevance, to nullify his chances of crossing national frontiers, to force him to remain confined within a local market to which imitation may be okay. Fortunately, this is not the case with Fontanari, who seems set on the right track.

The beginning of his research, of course, rests on the foundations of American Contemporary Realism, that is, the realism that began to develop in America in the late 1960s and that has experienced detours, derivations, and ramifications (all its exponents, Sidney Tillim acknowledged as early as 1969, “have a certain quality problematic that defines both their distance from each other and their distance from other kinds of supposedly figurative art”), that seemingly descriptive, apparently démodé and seemingly anachronistic realism, often flat and rapid, at other times more inclined to linger on details, which nevertheless offered a more or less direct commentary on contemporary society by measuring itself against Pop Art, Minimalism, and abstract art. Andrea Fontanari’s paintings recall in some respects the flat shapes of Fairfield Porter, certain cuts bring to mind Philip Pearlstein, scenes set outdoors evoke the crowded views of Eric Fischl. Also for Fontanari, as for Fischl, images spring from photographs, no matter whether they are compositions constructed with the photographic medium, memories fixed with the camera, or images scouted on social media. And then, like contemporary American realists, Fontanari also loves large formats. It is true: there is a lot of America in his art. But there are also the prerequisites to recognize a lot of Italy inside the paintings of the young man from Trentino.

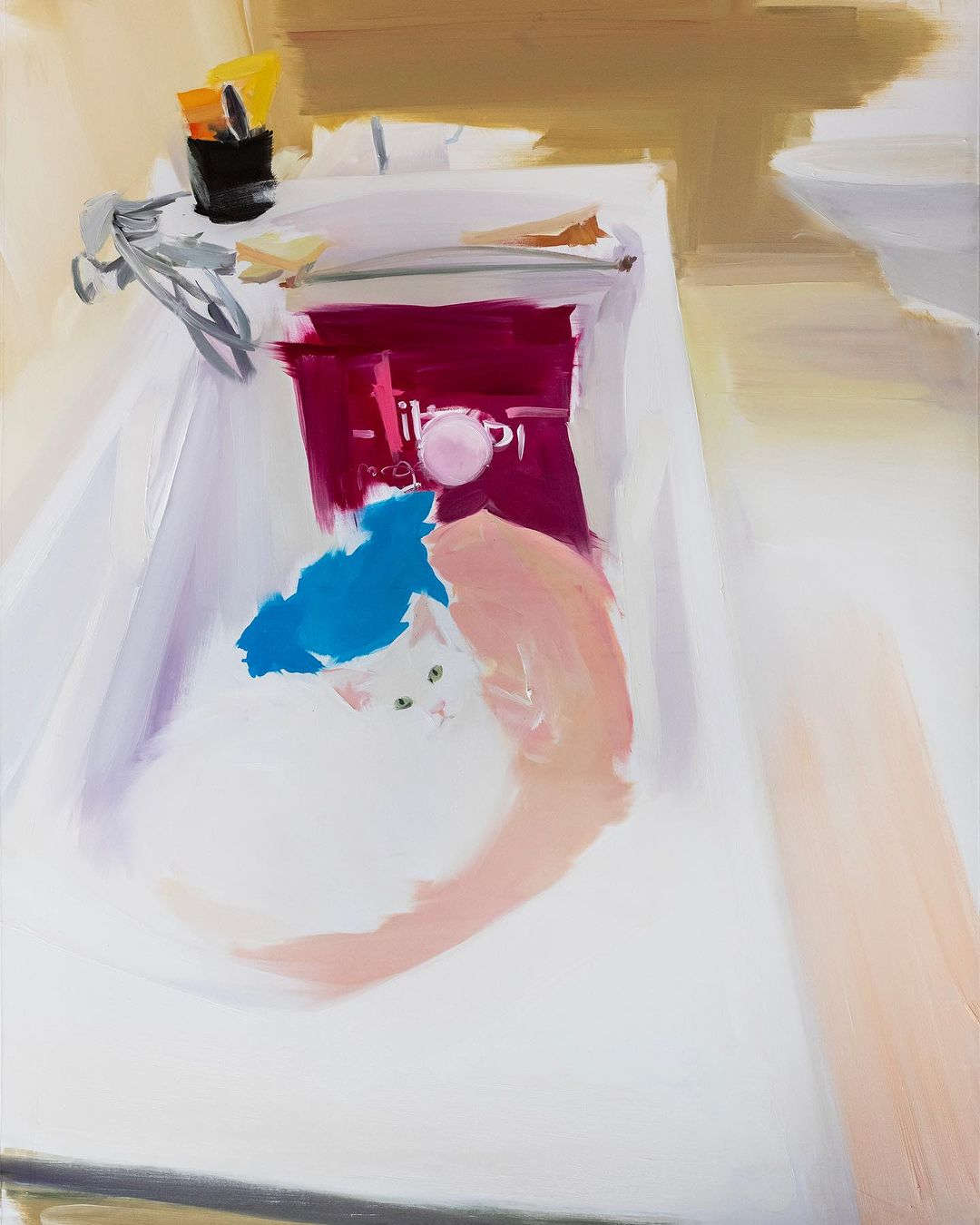

There is, meanwhile, a silent insistence on objects. An insistence that, without the need to go looking for the shores of Pop Art across the Atlantic, is common to so much postwar Italian art, from Gnoli to Ferroni, from Guttuso to Pozzati, not to mention the experiences of almost all the artists of the Scuola di Piazza del Popolo. Objects that, therefore, come to Fontanari by running along the paths of tradition. Objects that are as important in his art as human presences. Objects that are part of Fontanari’s daily experience. Objects that are part of everyone’s daily experience. An artist, however, is not a person like any other: he tends to look at the elements of his everyday life according to different insights and concerns than those of someone who is not an artist. Here, then, in Fontanari’s experience, in this relationship with the ordinary, in this intrusive nagging of the everyday, we seem to see echoes, in some ways, of Tano Festa’s objects: “for a long time,” Festa once wrote to Arturo Schwarz, “I have been looking at the objects of domestic furniture which, being the most private, are those with which we are most in contact, toward which we reveal the most intimate and secret acts and gestures of our existence. At first this interest was mainly of a formal nature, but later I began to establish a relationship of a psychological and emotional nature. [...] I thought of reconstructing objects that were mutilated of their functions, objects that in their physicality expressed a subtle restlessness in the face of their too easy and certain presence, a sense of ambiguity and impotence in the face of their physical, inorganic, obtuse being, and again a sense of mystery and impenetrability in their cold and dark geometries.” Tano Festa responded to this restlessness of the everyday by fabricating objects, notably doors and windows, and depriving them of their original function. A deprivation that was accomplished simply by transforming objects into works of art. For Fontanari, rather than responding to a disquiet, it is about removing a veil, it is about exploring the repository that lies beyond the screen of the usual. The everyday object is an inaccessible mask that hides its secrets behind that dim, muffled, inaccessible fixity; it is a hidden witness that sees everything, hears everything, records everything: joys, expectations, happiness, well-being, harmony, unity, pain, suffering, torment, anxiety, discord. For Fontanari, the object is the very symbol of the fragility of our existence, because behind an object there is a universe of affections, ties, memories. Behind an object, the artist seems to tell us, the ghosts of our lives stir, hiding traces of what no longer exists or what will be. The places we have been. The rooms we have lived in. The people we met and never saw again. The hopes for the future. And there are also the collective anxieties. One of his large canvases depicts a very ordinary red telephone: it turns out that it is inspired by the Siemens model in use by the Wehrmacht during World War II, and the one painted in Das rote Telefon, in more detail, resembles the telephone that was found in Hitler’s bunker, which was sold at auction in 2017 for the sum of $243,000. Another work, from 2017, has us enter a hotel room with an unmade bed, with a striped pillow unwittingly evoking a visit to Dachau. In yet another there is a globe, the kind that lights up showing the borders of the countries of the Earth when they plug in. Two times coexist in the painting, since in the western portion of the globe the borders are better distinguished, while on the other side they are barely perceived, mountains and deserts can be seen, a physical geography appears, the description of a globe that, were it not for human beings, would know no barriers.

Fontanari then operates a shift that subverts the status of the object with the sole medium of oil painting, and that object, from being a silent and passive observer, becomes the leading actor in a lively performance aimed at sharing that intimacy that was previously only the artist’s. Telling all that is hidden behind an object. And thus telling the story of life. For the exhibition Monumental Ordinary, the objects were all painted on large canvases, more than two meters high each, sometimes even more imposing: here is a chair, a flower, a telephone, a globe, a tea set, even a bidet and a toilet bowl (in two separate paintings, of course). Monumentality is the response Fontanari employs in regard to the ambiguity inherent in objects. As it was for Gnoli, for Fontanari, even with all the differences that divide the two artists (Trentino lacks the solemnity, the scientific detachment of Gnoli, his sense of suspension), to elevate the scale of the ordinary to the monumental is to bring out the invisible that lies behind the subject of the painting. But for Fontanari, the monumental is also the medium through which the object releases its energy, that energy that is essential to leave the artist’s inner self and necessary to open up to all. “In my paintings,” Fontanari explains, “I try to represent life. I would like not only for the paintings to capture its energy, but also for them to become themselves part of our experience. A small painting is under our control: in large paintings, it is he who welcomes us into his dimension, and it is we who must walk through it to read it in its entirety. I seek a coincidence between the reality I represent and life.” This does not mean, he is keen to add, "that small-format paintings cannot enclose within them a world. The great masterpieces of art history are often small format. But with Monumental Ordinary I wanted an exhibition that would be a kind of manifesto of the energy that painting can have in telling the story of life."

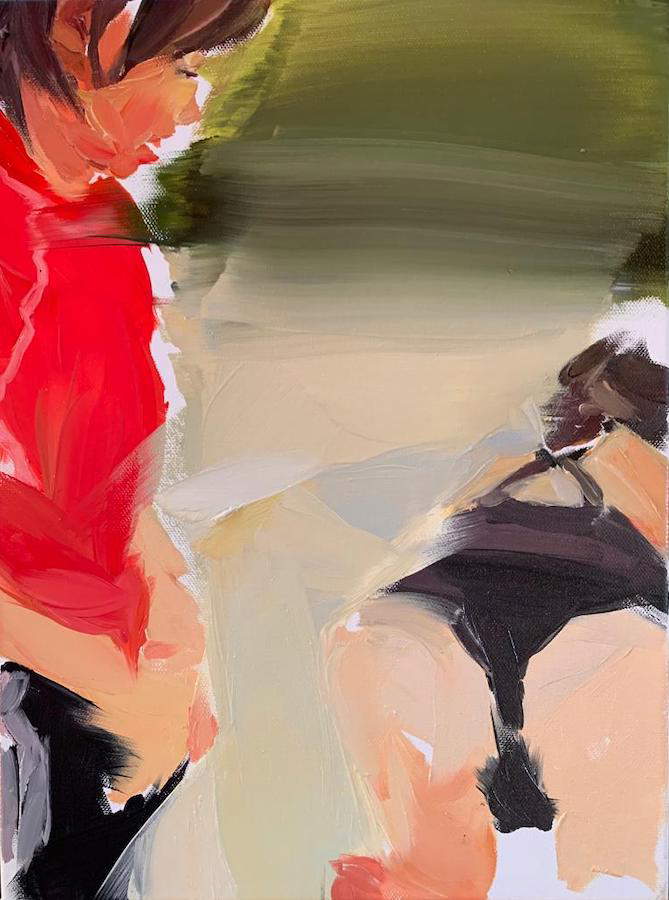

A more international attitude and more inclined toward Contemporary Realism is the one that cloaks instead the episodes of everyday life involving the presence of human figures, almost always caught in moments of leisure, rest, relaxation, almost always unrecognizable, given Fontanari’s inclination toward forms rather than content. There is almost no room for the anecdotal in his paintings. They are simple snapshots of life, almost always taken subjectively, as if Fontanari wants to invite us to become part of that quotidianity he recounts. And it doesn’t matter if the quotidianity is his or someone else’s.

We enter a bedroom and become a couple lying in front of an open window. We relax in a living room watching television. We find ourselves outdoors in front of a girl climbing down a ladder. We walk on the beach behind a small family approaching the sea. We are above a meadow, with a child coming toward us running on a unicycle. We are driving a car with someone next to us who is resting feet dressed in Converse model booties on the dashboard. We are standing still inside a dark room, next to a boy looking into an Ultrafragola mirror. Or standing, slightly bent over, inside a small living room cluttered by the presence of a Thonet rocking chair (and, incidentally, this attention to design on Fontanari’s part is also all Italian), with a floral patterned shirt thrown over it and a pair of red pumps on the floor. Some of these paintings belong to a series that the artist has called Diary: paintings that are like pages of a diary devoid of gasps, common, intimate and open, personal and collective, a diary that could be everyone’s. A diary that invites us to consider how the ordinary is precisely what we must learn to see better, to discover more: we take it for granted, but everything is possible in the ordinary. “The process of artistic creation,” writes Richard Deming in his Art of the Ordinary, “absorbs things as they are, but there is a tension between trying to present them directly and having the transformative process of art reveal itself [...]. A painting, poem, or song can enrich an experience of the world because they introduce a new perspective that complements the way a person sees the world. In other words, whatever else they may do, works of art help teach people how to look at things. The relationship between the viewer and the thing seen changes, and with it the experience of the meaning of that thing. A viewer can look at the scene as an artist does, feeling it full of potential meaning. Through painting the everyday remains everyday: it is attention to the everyday that is transformed through art. That is to say, the everyday does not change because of art: it is we who change.”

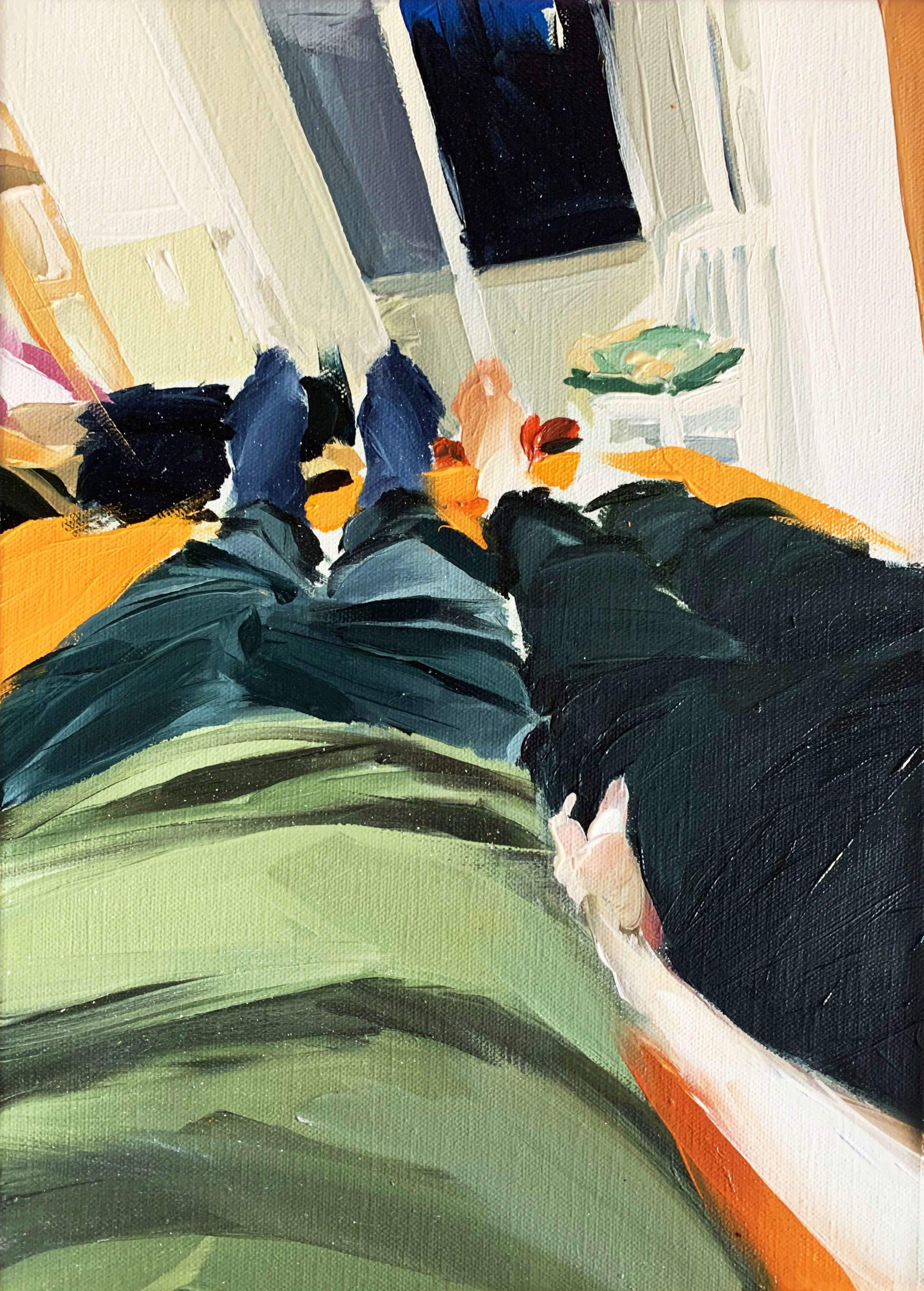

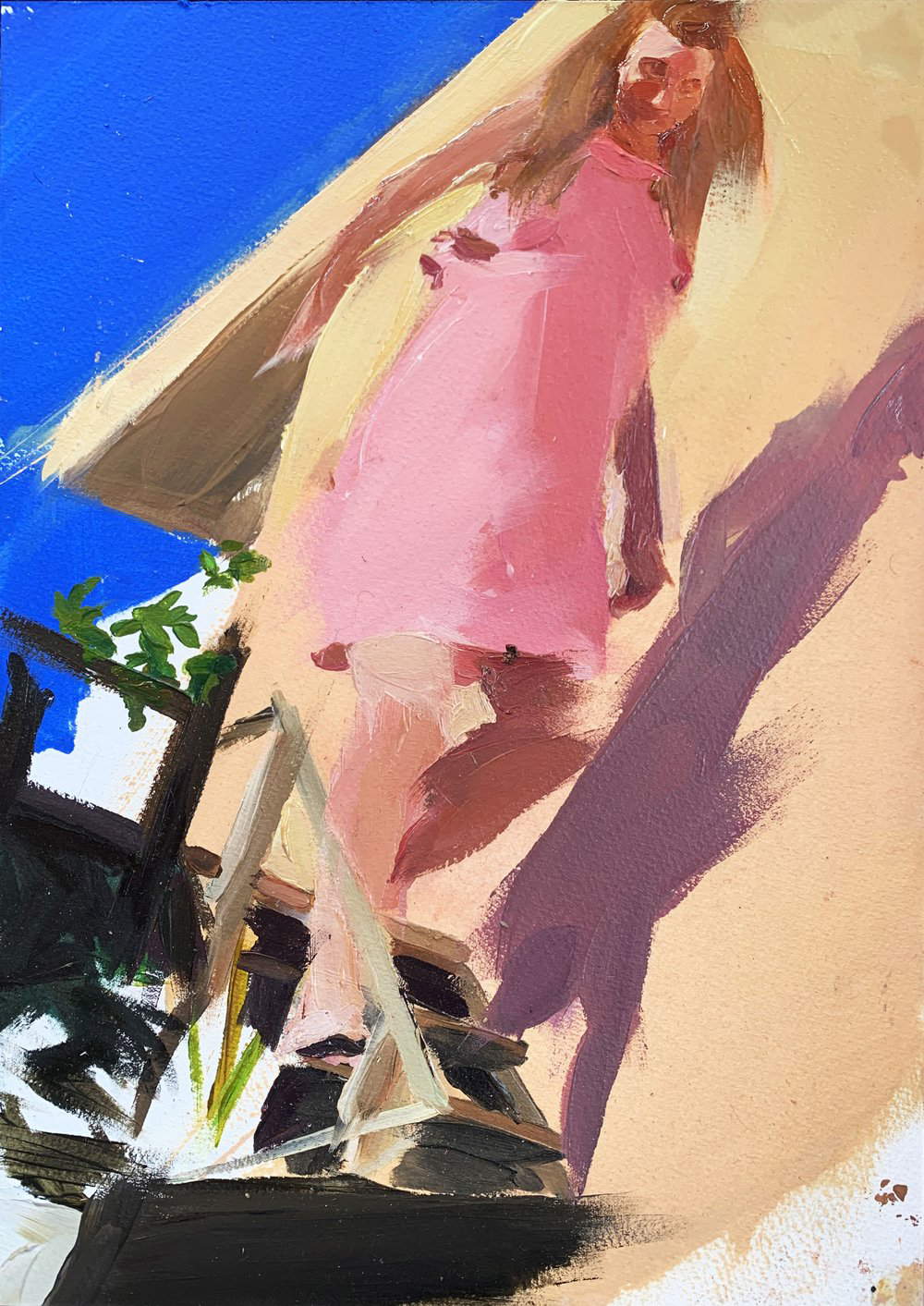

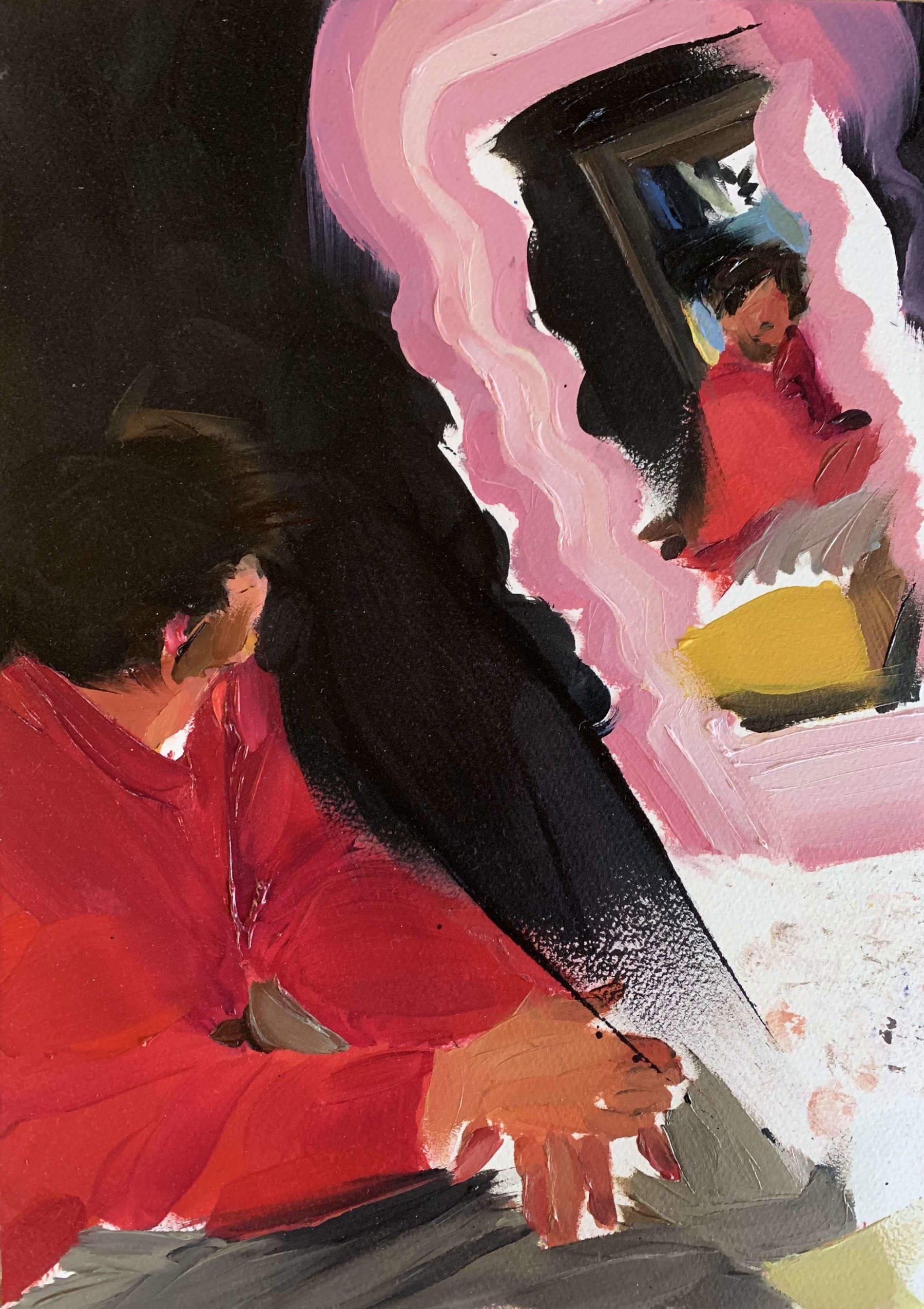

To express and to get this fullness of potential meaning across, Fontanari transfigures his scenes by working on cuts, light, shapes, and color. His paintings are almost always constructed with color: it is difficult to find compositions born from a drawing, and when it is present it means that the initial idea was more complex than usual. The most recent works, those between 2023 and 2024, for example Motherwell or Sly Boy, show an accentuation of that unfinishedness that has often characterized his production, as well as a marked, unprecedented orientation toward abstraction: it is toward this direction that his painting is moving, so in the future we will presumably expect similar images, images with which Fontanari will continue to deepen these experiments. And in the Italian tradition there is a lot of very, very good abstract painting, of which the Trentino artist we know is a careful observer. The basic toolkit, however, has remained the same as always: photographic cuts, the underpainting that looks biasedly at the art history of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, a terse and dazzling light that does not allow for subdued contrasts, every now and then some surprising, savory backlighting effects, the colors that over the years have become increasingly saturated and vivid and are arranged on the canvas forming almost uniform masses, the forms built by means of a liquid, rapid brushstroke. Certain outdoor scenes are reminiscent of the painting of a Sorolla or an Ettore Tito: the Spaniard for his extreme fluidity, the Venetian for his movement and photography-oriented compositions, dense with sloping views, close-up planes, daring cuts. Fontanari no longer uses the kodak (or at least not only), but he has updated himself on social networks: his snapshots retain the delicate fragrance of the memory of an afternoon on the beach or in the mountains captured with the speed and awkward positioning of a cell phone camera and then uploaded to Instagram or Facebook. His painting seems almost a way to save these shots, which are often forgotten as quickly as it takes toupload to social networks. That of the painter from Trentino, after all, is also a work of appropriation, since his paintings often arise from images found by chance on social networks. “They are a great resource,” he tells me, “even for us artists: I’m especially interested in the way we use it beyond the work, in the way people share moments of their private lives to a larger or smaller audience. They are a great source of inspiration for me: they have changed our perception of reality. I’m not interested in having a critical or judgmental eye; instead, I’m interested in investigating the aesthetic proposals that the contemporary world shows us and in investigating the human need to look at and be part of the lives of others.”

Perhaps it is also from these considerations that we need to start in order to find possible answers to the question that often arises when, today, in the twenty-first century, we come across an artist who has devoted himself to the figurative, and even more so if he has decided to follow the path of realism. Why paint realistic works? Peter Schjeldahl had already asked himself this question in 1981 after visiting an exhibition of Contemporary American Realists, and to find the answer he thought of Rackstraw Downes’ paintings, which had made a great impression on him because, alone in the entire exhibition, they caused him to think more about the world than about art. And, one might add, your world can surprise you all the time even if you lead an ordinary existence. The same can be said for Fontanari. Andrea Fontanari’s art weaves present and memory to compose an ode to the mystery of the mundane; it is a poetry of the everyday tinged in the light of a summer day. His painting employs the means of an original realism based on tradition, luminous and immediate, cultured and accessible at the same time, to induce the viewer to grasp the sparks of enchantment that everyday life is capable of releasing. His paintings urge the viewer to look beyond the surface of the canvas, to look at his world, without the need to go too far. They are an invitation to discover the wonder of the ordinary that surrounds us.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.