In the Paris of the early 1970s, it was not uncommon to come across a man with a bizarre appearance: tall and thin, dressed as a modern bohemian, long hair framing a face with vaguely Middle Eastern features, a gaze always absorbed to the point of looking constantly lost. And with a strange, colorful wooden bar always on his shoulders. His name was André Cadere (Warsaw, 1934 - Paris, 1979) and he was a young man who had wanted to leave the dictatorship behind: he was in fact from Romania, and it is said that he did not have a very easy life. Too free-spirited was his spirit to survive a regime as rigid as Ceau�?escu’s. He had, however, managed to get some practice in painting through the courses he had taken at theBucharest Academy of Fine Arts, where he had taken classes for some time with one of the most fashionable Romanian painters of the day, George Saru. The situation, however, must have been untenable to the point that it led him, in 1967, to the decision to leave Romania never to return. This was the turning point, the year that changed André’s life, and from here on he would begin to carve out a space for himself to enter art history.

|

| André Cadere |

|

| André Cadere, Sans titre (1968; oil on canvas, 129.5 x 195 cm; Paris, Centre Pompidou) |

But it was in 1970 that his art experienced a decisive turning point. By 1968 André had already realized that Op Art had said all it needed to say, that the artistic environment in Paris was far more advanced than that in Bucharest, and that the time had therefore come to update. Thus, two years later, the artist began to produce objects that would become practically his only form of artistic expression: they are round wooden bars, composed of many overlapping colored cylinders, sanded, stained, and hand-painted in pure, always garish hues: greens, reds, yellows, blues, sometimes even whites and blacks. Until 1971 they also consisted of cubes, but throughout the rest of his career the preferred shape would be precisely that of the cylinder. The height of these sticks varies: from a few centimeters to almost two meters in length. They are strange works, seeming to have neither a head nor a tail; it is not clear which way to look at them, whether there is a bottom and a top, whether looking at them vertically is the same as looking at them horizontally. André is certain of one thing, however: writing a letter to his friend, English art historian Lynda Morris, in 1975, he tells her that "the scientific name for my work is not sticks, but round wooden rods." It is a unique work in the art scene of the time.

|

| André Cadere, Round Wooden Bars (1973; painted wood, 155 x 3 x 3 cm; London, Tate Modern) |

|

| André Cadere, Six Round Wood en Bars (1975; painted wood, 120 x 10 x 10 cm; Paris, Centre Pompidou) |

|

| André Cadere, Cubic Wooden Bar (1971; painted wood, 196.2 x 4.8 x 4.2 cm; Madrid, Museo Reina Sofía) |

|

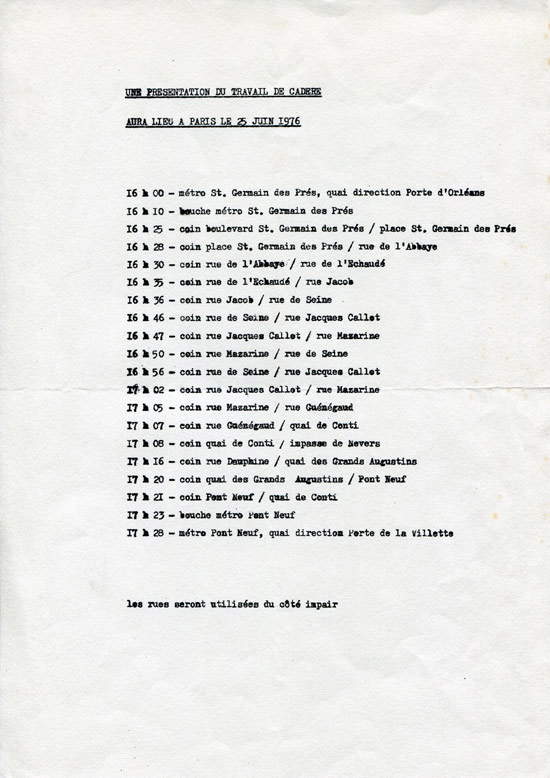

| Flyer announcing a “Presentation of André Cadere’s work” on the streets of Paris. |

|

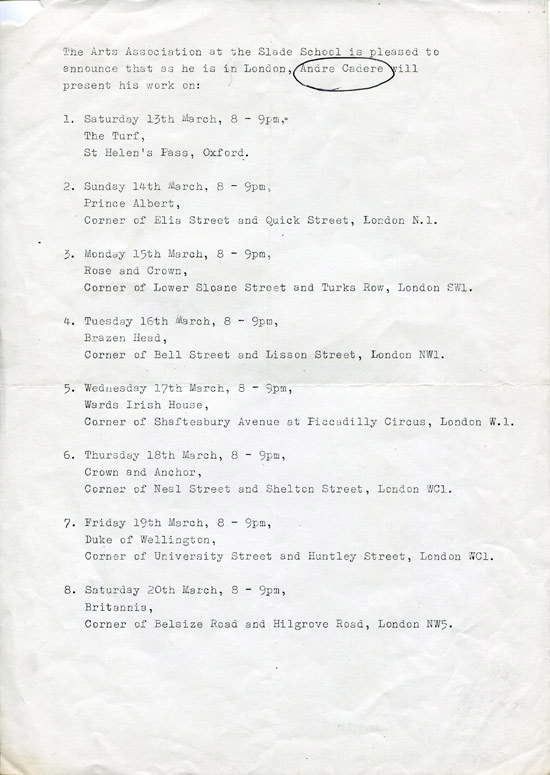

| Flyer for London pub nights. |

Public spaces proper, however, are not the only places where André takes his colorful objects. In fact, the artist also begins to crash presentations to which he is not invited, obviously always carrying one of his bars with him (it seems that, from 1970 until the last years of his life, André Cadere produced about one hundred and eighty of these objects). It is a kind of protest, as André himself would explain in 1974: “The power of museums and galleries consists first of all in the power to choose: we are not really free. And if it is not possible to destroy this power, it is at least necessary to show it...and it should be emphasized that this way of unveiling power is entirely peaceful and nonviolent. A round wooden bar is materially a small object that does not prevent an exhibition from taking place. The struggle takes place on an essential, ideological level: aggression and violence are always employed by those with power.” If an institution makes a choice, André’s innocent little bar puts the emphasis on the fact that that gallery, at the moment it chose, also made the diametrically opposite operation, that is, it excluded, perhaps often according to criteria that have little to do with art.

And of the fact that he is an artist who is not easily tamed, André gives a splendid demonstration in 1972, when the Swiss critic Harald Szeemann, who despite the age of thirty-nine is one of the most powerful and in-demand curators in Europe, invited him to Kassel, Germany, to the fifth edition of dOCUMENTA, an exhibition of contemporary art that was then and continues to be today one of the most important in the world. Szeemann had been fascinated by the figure of that Romanian who was always wandering around Paris with his works: a sort of pilgrim of contemporary art, a meditative wandering traveler who opposed his calmness, his peacefulness and, of course, his art to a frenetic world, and moreover a Romanian, thus coming from a land generally little known to Western Europeans but with centuries-old traditions, something that would also add exoticism to a mix probably considered to be a sure success. Participation in dOCUMENTA 5, however, is tied to one condition: André must make the journey from Paris to Kassel on foot, bar on his back, of course. This is also to evoke the journey that his great compatriot, Constântin Brancu�?i, had made, also on foot, when he left Munich to move to Paris. In short, André’s would have been a performance full of references and suggestions, according to Szeemann. Fall agrees, but pretends to travel on foot: he buys a series of postcards of the cities along the route between Paris and Kassel, and then sends them to the dOCUMENTA 5 organization by falsifying the dates. In Kassel they believe the artist is really making the journey on foot, but they realize they have been duped by reading André’s latest communication: the train schedule from Paris to the German city. And indeed, it is by train that André arrives in Kassel: Szeemann and the organizers of dOCUMENTA 5 are on a rampage and forbid the artist not only to show his work in the exhibition, but even to approach the venue. Cadere reacts by spreading protest leaflets and spray-painting, on a wall in Kassel (after obviously taking a walk of his own), a sequence of colorful shapes reminiscent of his bars. This is the first time the art world has had to deal with André Cadere’s irreverence outside French borders.

|

| André Cadere with one of his bars in Paris, at the Musée Rodin, in 1972 (from The Single Road) |

|

| André Cadere at the opening of an exhibition (from the book Photographies de Vernissages by Jacques Charlier) |

|

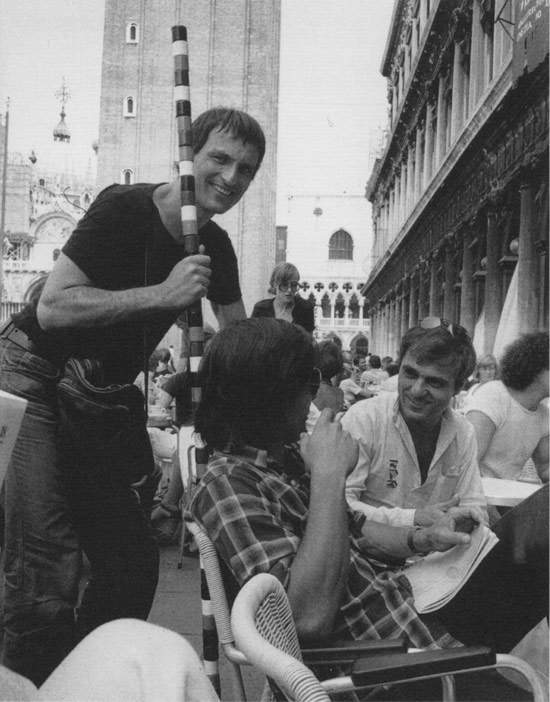

| André Cadere in Venice (from The Single Road) |

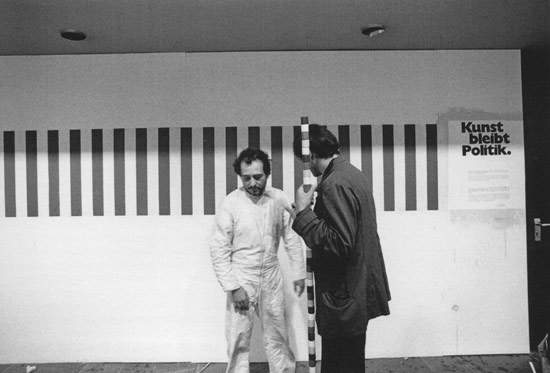

An irreverence that had made him unlikeable not only in Szeemann’s eyes. In the same 1972 he was thrown out of the Grand Palais in Paris, where the opening of a retrospective of the American Barnett Newman was in progress. Memorable then are the numerous clashes with Daniel Buren, probably the number one “enemy” of André Cadere: the two artists in fact create works that are apparently similar, but in reality ideologically at the exact opposites (a big difference between the two consists in the fact that Buren creates site-specific works, thus requiring a precise space in order to be shown and necessarily depending on that space, something that Cadere’s bars, in their total freedom, have no need of). Cadere does not fail to sneak into the openings of his rival’s exhibitions, which he often reacts to furiously, as when, in 1973, he learns that a group show in Belgium will also be attended by André, albeit not officially invited: the exhibition then does not start due to organizational problems, but the only work that is already in the gallery rooms even before the opening is precisely a wooden bar by Cadere. It must be said, however, that in 1974, when Buren was expelled from the 1974 Projekt exhibition in Cologne for his intervention on behalf of another censored artist, Hans Haacke (the latter had created a work revealing links between one of the exhibition organizers and the Nazi regime), André protested his colleagues’ exclusion by showing up in Cologne with one of his bars wrapped in paper. And again in 1974, at the vernissage of a Valerio Adami exhibition, André is stopped at the entrance, and the staff of the Galerie Maeght in Paris intimates that he must enter without the bar he carries on his shoulder. The artist agrees and leaves the bar at the entrance, but once inside the exhibition, he pulls a hidden, smaller one out from under his clothes.

|

| André Cadere with Daniel Buren at the 1974 Projekt exhibition (from The Single Road) |

Indeed, André’s bars always take on different sizes and color combinations that are never identical (although the artist always uses between three and seven colors). The fact that the bars consist of an assemblage of small cylinders and not a single piece painted in various colors hints at André’s own conception of color. In a lecture-presentation of his work at the University of Leuven in 1974, the artist had given this example: if we open a transistor we see that there are many colored wires inside. But it is not that they are colored because someone wanted to make the inside of the transistor beautiful: they are colored because each wire corresponds to a function, and the color serves to distinguish those functions. The same happens with his rods: if in a painting hanging on the wall all the colors contribute to the goal of creating a unique composition, in André Cadere’s works the cylinders serve to manifestly indicate that each color has a precise and distinct function.

But what are the artistic and stylistic assumptions of his bars? There are those who have wanted to identify in the Round Wooden Bars a debt to minimalist art, in particular the conception of art according to Sol LeWitt, for whom there is a profound difference between concept and execution, and of course the greatest importance rests with the concept: “when an artist deals with conceptual art, it means that all decisions are made in advance, and the execution becomes a small affair. The idea becomes a machine that produces art.” Add to this the fact that the minimalist art of artists such as Judd and LeWitt had, as its main characteristics, repetitiveness, formal simplicity, and the use of algorithms-all traits that recur in the art of André Cadere. However, Cadere refuses to attach little importance to the execution: his wooden cylinders are painted by hand and, unlike the minimalist artists, he himself is in charge of the making of the works. Indeed: to better show that the bars are created by hand, André often deliberately misaligns the cylinders so that the bar does not appear perfectly straight. These are contradictory works: repetitive and serial, almost as if they came out of an industrial production, but each with its own soul, with small unique errors (“if the error were reproduced, it would no longer be an error, but a new system,” says the artist), with colors that follow patterns produced by algorithms but that always contain, too, at least one error (the error, in this case, consists in subtracting a color from the logical sequence of the series: Cadere himself explained with diagrams the ways in which errors could be introduced into the compositions). And error, which minimalism rejects, has a precise function: To establish disorder, as per the title of one of his 1977 presentations.

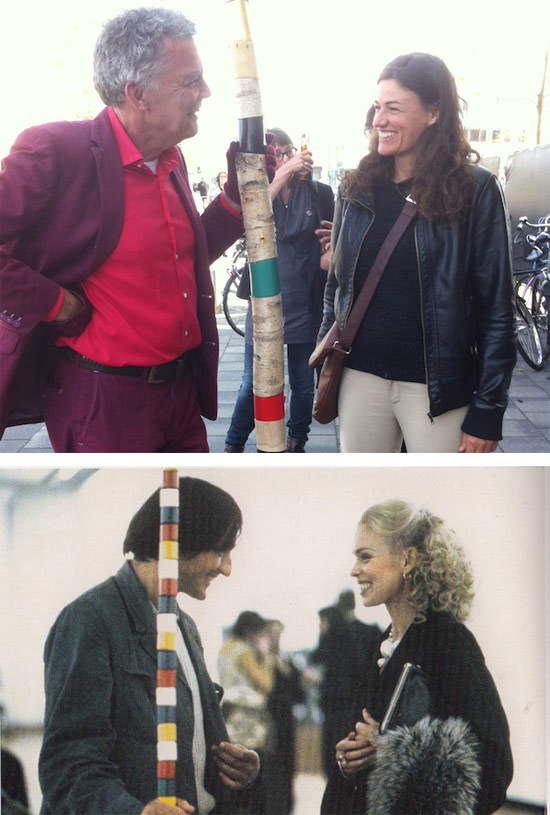

And establishing disorder in the world of apparent order is what André Cadere did all his life, cut short prematurely by cancer in 1979. Establishing disorder: a small revolution, “peaceful and nonviolent,” carried out against everything and everyone perhaps also to open the eyes of the public to the true function of art, and perhaps (why not) to get the message across that art does not belong to critics who choose artists and works according to their own often far from transparent yardsticks of judgment, and that it does not belong to museums and galleries that are increasingly self-referential and distant from the people either. No: perhaps André Cadere really wanted to tell us that art belongs to everyone. Today we are reminded of this by his Round Wooden Bars, which, paradoxically, we admire in museums around the world, because now even his art has become institutionalized. But perhaps better still, we are reminded of him by those who, several decades after his passing, continue to pay homage to him with performances similar to his, which bring art down to the street, carrying on, with the cheerfulness that always distinguished André Cadere, that desire to “establish disorder” in a world that is too often plastered, narcissistic, and capable of thinking only of itself, like that of art.

|

| The two artists Frank Bezemer and Scarlett Hooft Graafland re-enact, in Amsterdam in 2015, the image with the meeting between André Cadere and Isa Genzken in Bruxellese in 1974 (from Frank Bezemer’s website) |

Reference bibliography

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.