An Italian antiquarian complicit with the Nazis: the Ventura affair

Among the trades, often illegal, of works of art that Italian antiquarians carried on with the emissaries of Hitler and Marshal Hermann Göring, in the years before and during World War II, is the Göring-Ventura exchange, an emblematic case of collaborationism in the export of works of art from Italy to Germany, which reveals sad backstories, which involved, not only antiquarians, but also officials of the Fine Arts and well-known scholars. A case that also makes us understand how delicate and fundamental were the negotiation phases with the Allied Services, American and British, in the economy of the restitution of artworks stolen in Italy.

We are given an idea by Rodolfo Siviero, who, as head of the office responsible precisely for the recovery of works of art stolen by the Nazis, played a fundamental role in the affair. Let us reread his point of view, through the words written in the essay Exodus and Return of Italian artworks removed during World War II. Known and Lesser Known Stories (the text is found published in L’opera ritrovata: omaggio a Rodolfo Siviero, catalog of the exhibition held at Palazzo Vecchio in Florence in 1984, thus posthumous to Siviero’s death in November 1983):

the most difficult problem still remained that of Hitler’s and Göring’s illicit purchases that they, since 1937, had committed with the complicity of Italian antiquarians. Göring went so far [ ] as to carry out an exchange of paintings seized by the Gestapo from French Jews for works of art in the possession of a Florentine antiquarian. Having tracked down in Florence the nine Impressionists (works by Van Gogh, Cézanne, Degas, Utrillo, Renoir) [in fact, works by Utrillo were not found, but by Monet and Sisley, along with those of the others correctly mentioned by Siviero], I handed them over to the French ambassador in Rome amidst a swarm of protests from pseudo-jurists who demanded that first the Italian works that Göring had received in exchange be returned. Instead of these works I obtained, for Italy, that the French not take the antiquarian to Paris to try him. Fortunately, at these junctures many friends rose up in indignation; among the ministers and cultural personalities I still remember, Benedetto Croce, Alcide De Gasperi, Enrico Molé, Carlo Sforza, Ranuccio Banchi Bandinelli [ ] At the Collecting Point [in Munich a group of paintings from this exchange was being found, including a beautiful Domenico Veneziano .

In order to clarify and contextualize Siviero’s words, however, a clarification must be made: in the years leading up to and during World War II, Hitler and his Marshal Hermann Göring, the Number Two of the Nazi regime, perpetuated, in addition to the other terrible and much better-known crimes against humanity, a massive despoliation of works of art throughout Europe and especially in Italy and France. Hitler’s primary aim was to create in Linz, Austria, the largest existing Museum of Fine Arts in the world, which would collect the valuable artifacts looted at the expense of the great museums and the most important private collections, especially if the owners of the latter were Jews. Obviously, in this museum there would be room only for works by so-called classical artists (from the Primitives to the artists of the Italian Renaissance, from the seventeenth to the nineteenth centuries), excluding art considered degenerate, not in line, that is, with the aesthetic ideals imposed by the regime. The works requisitioned and belonging to the latter category served as bargaining currency, particularly in dealings with Italian, especially Florentine, antiquarians. In this practice the real specialist was, indeed, Hermann Göring. The favorite targets to hit were Jews fleeing Nazi persecution. The works that Göring raided from these then flowed into his personal and private collection, a kind of temple, where he could enjoy their beauty in solitude, called Carinhall, named after his first wife, Carin. It was located near Lake Dollnsee, sixty-five kilometers north of Berlin.

To acquire the works he was interested in, Göring often used emissaries. First and foremost was Walter Andreas Hofer, since 1937 his personal art adviser. At other times he personally went to the trading/trading places. He was in Paris often to get his hands on collections seized from Jews and deposited by the ERR at the Jeu de Paume in Place de la Concorde. In this museum, now deputed as a collection point for the German raids, the works remained waiting to be personally selected by Hermann Göring. At the request of the then director of the French National Museums, Jacques Jaujard, the young Rose Valland worked at the museum, who, an eyewitness to everything that was happening inside the museum, gathered as much information as possible about the trafficking and movement of the works of art. Information that she then communicated to the Resistance, which in turn tried to intercept the means on which the works were traveling to Germany. Valland also did a punctilious job of gathering information on all the works collected at the Jeu de Paume. This work later proved most useful in the recovery operations at the end of the war. Parallel and analogous to Valland, Rodolfo Siviero was working in Italy, who, thanks precisely to the information gathered by the French scholar, later passed on to the Allies, in the summer of 1945, was commissioned to investigate so that it would be possible to recover some paintings stolen in France by Göring and which, in all probability, were in Italy, particularly in Florence, which ended up in the hands of the antiquarian Eugenio Ventura. The affair had wide repercussions on the Italian and international public opinion, which followed the various implications through what was written in the daily press.

On August 10, 1945, at the request of the Ufficio Recupero Opere d’Arte, under whose command was Siviero, and of the Allied Subcommission for the Arts in Italy, the Command of the Internal Company of the Carabinieri in Florence ordered the arrest of the Florentine antiquarian Eugenio Ventura, who had to disclose the hiding place (the Convent of San Marco) of a nucleus of works that he owned, but whose provenance was being investigated. From the various interrogations to which Ventura and others involved were subjected, the following details emerged. Ventura stated that he had received an initial visit from Hofer, director of Marshal Göring’s art galleries, in the fall of 1941. The offer he received was to exchange works he owned, among the most valuable in his collection, for French Impressionists that his collection actually lacked. Subsequently Ventura first had photographic reproductions sent to him so that he could have the works evaluated by those in authority, in this case Roberto Longhi, and then he had the paintings delivered personally by Hofer. The negotiations between Göring and Ventura went on until March 8, 1943, when the deal and the exchange of the works were concluded. Ventura also admitted that he had, in the recent past, negotiated other sales of works destined for Germany, on behalf of other Florentine antiquarians, which investigations revealed were also Bellini and Contini Bonacossi.

Giovanni Poggi, then superintendent of the Galleries for the Provinces of Florence, Arezzo and Pistoia, was called upon by the Investigative Squad to clarify the behavior taken by Ventura, with regard to the Superintendency, on the occasion of the exchange of works made with Marshal Göring. His statements turned out to be unclear and even contradictory, betraying the fact that the Soprintendenza had become aware of the arrival in Italy of the French works, but had not forwarded regular reports to the competent authorities. Similar statements were made by the director at the Soprintendenza alle Gallerie ed alle Opere d’Arte for the provinces of Florence, Arezzo and Pistoia, Ugo Procacci. The name of Roberto Longhi also emerged. The latter was also heard, and when asked about the provenance of the works of ancient Italian art owned by Ventura, found together with the French works, Longhi replied that they came from the Gentner collection purchased by Ventura. Regarding the purchase of the Gentner collection, on the other hand, several suspicions emerged, in particular that the sale had been carried out under entirely malicious conditions, and the investigation confirmed this: Ventura had threatened the notary who signed the deed that awarded the sale, flaunting his acquaintances, in this case Senator Morelli and Mussolini, and stating that, in any way and by any means, he would obtain of them the successful bidder under the conditions he wanted and when he wanted.

Ventura was questioned again and confirmed that those found in the St. Mark’s convent were works that had remained in his possession since the purchase of the Gentner collection. The most serious admissions, however, made in the second interrogation by Ventura, were those concerning the continuity of his relations with representatives of Marshal Göring and first among them, the well-known Hofer who had already been frequenting Ventura’s residence for several years, albeit for artistic reasons.

After the seizure of the works owned by Ventura, the nine paintings by French painters were taken in charge by the ministerial authorities, brought to Rome and kept at the Galleria dArte di villa Borghese to then be shown to the public in the very capital on the occasion of the Mostra dArte Francese held at Palazzo Venezia, under the custody of Ranuccio Bianchi-Bandinelli, then Director General of Antiquities and Fine Arts, who took charge of coordinating the restitution operations. It took place, after various bureaucratic hiccups, on November 28, 1946: the works were delivered to the were kept at the premises of the Commission Récupération Artistique in Paris, waiting to be returned to their rightful owners or their heirs.

|

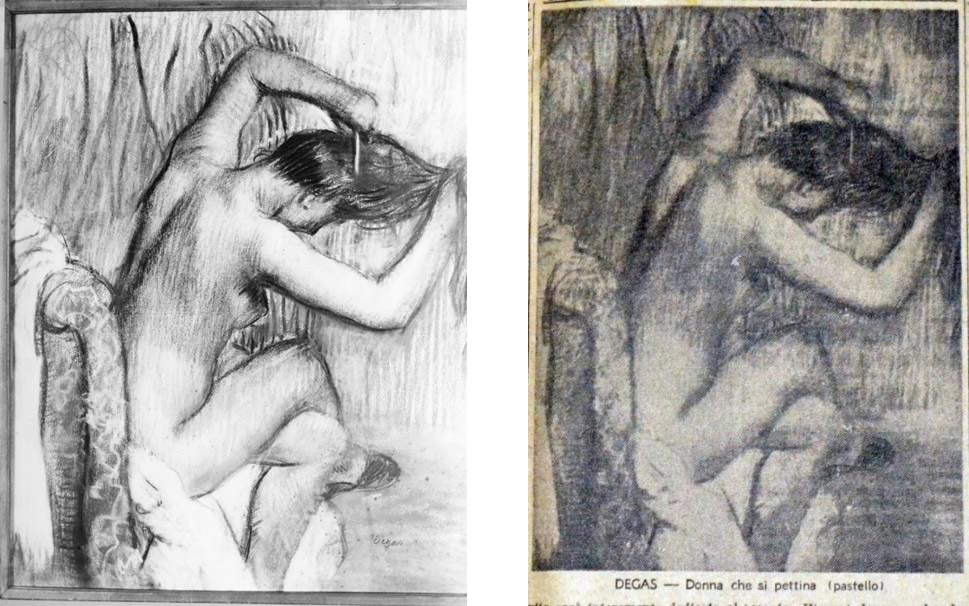

| Left: Photograph relating to the record of the Edgar Degas work, Woman Combing Her Hair given by Goering to the Ventura, in Die Kunstsammlung Hermann Göring, online database of the German Historical Museum. Right: Degas, Woman combing her hair, photograph published in La Nazione del Popolo, Aug. 17, 1945, digitized from the newspaper preserved at the Rodolfo Siviero House Museum. |

|

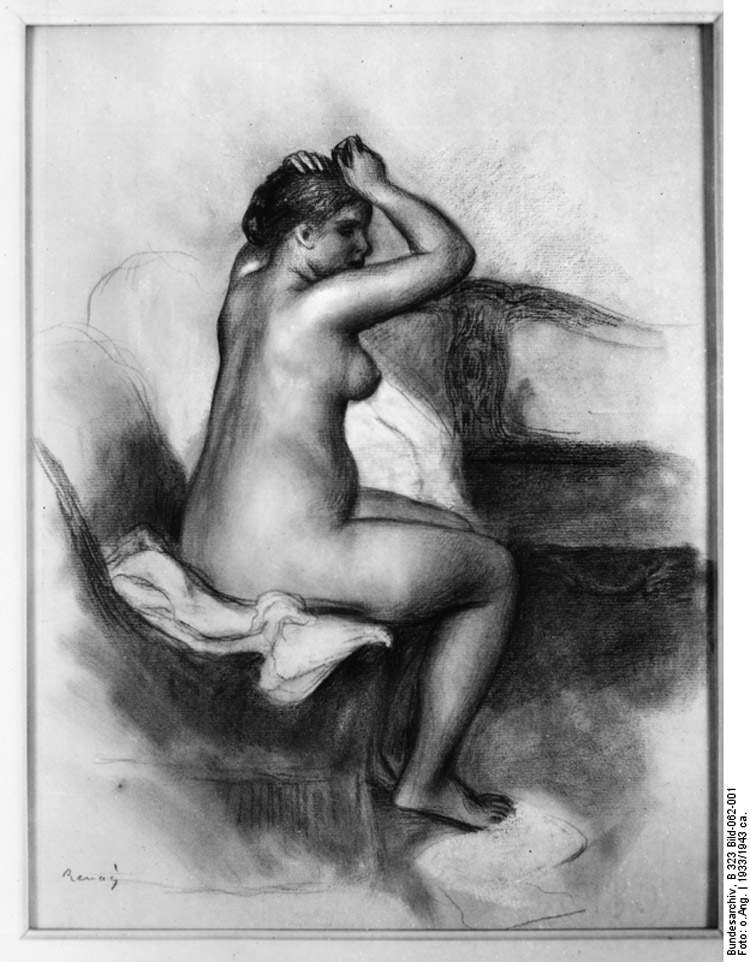

| Pierre Auguste Renoir, Seated Female Nude, photograph related to the file of the work given by Goering to Ventura, in Die Kunstsammlung Hermann Göring, online database. |

|

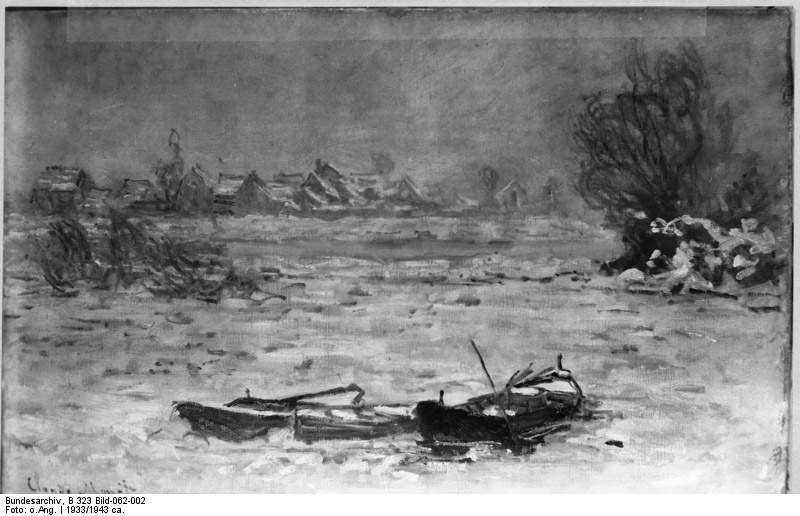

| Claude Monet, Les glaçons, photograph relating to the file of the work ceded by Goering to the Ventura, in Die Kunstsammlung Hermann Göring, database on-line. |

|

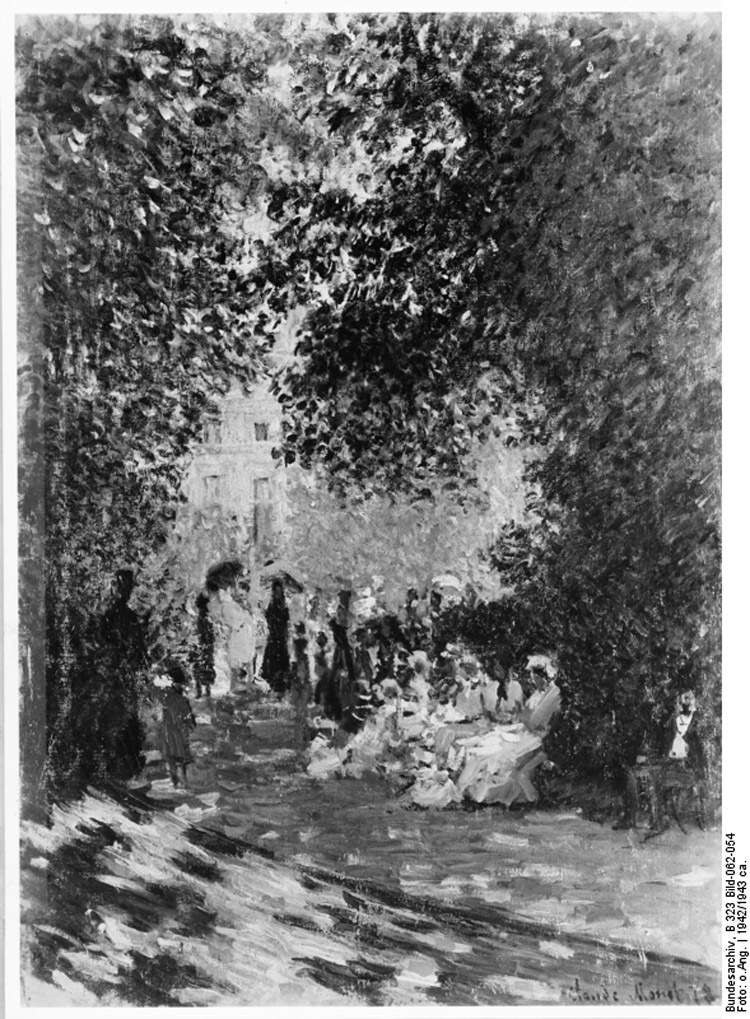

| Claude Monet, Parc Monceau, photograph relating to the file of the work ceded by Goering to Ventura, in Die Kunstsammlung Hermann Göring, database on-line. |

|

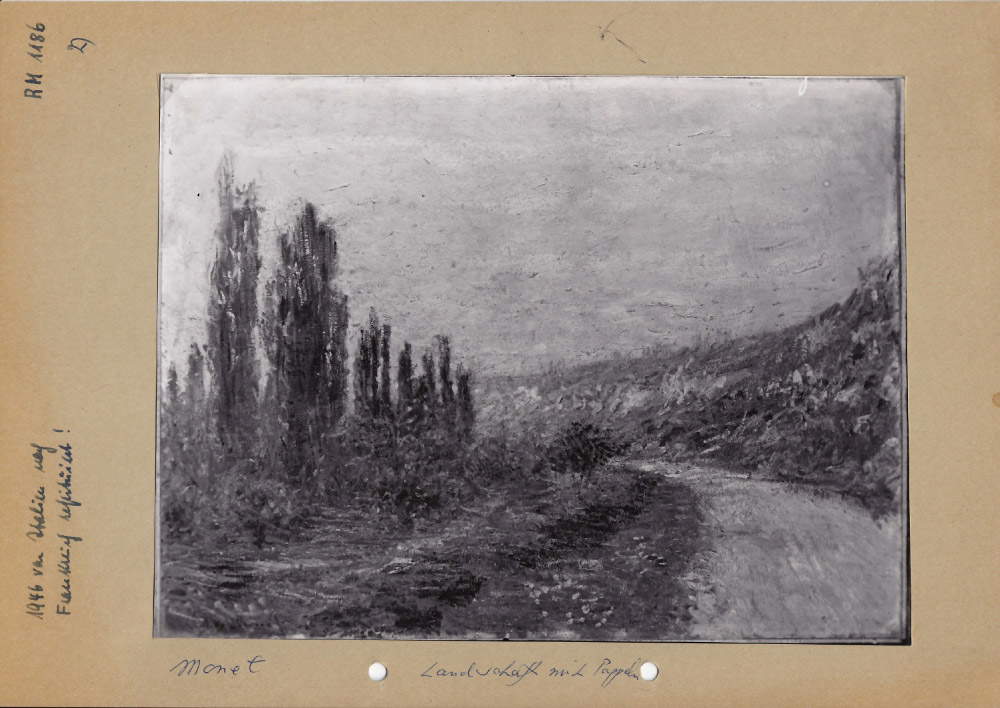

| Claude Monet, Route de Vétheuil, photograph relating to the file of the work ceded by Goering to Ventura, in Die Kunstsammlung Hermann Göring, database on-line. |

|

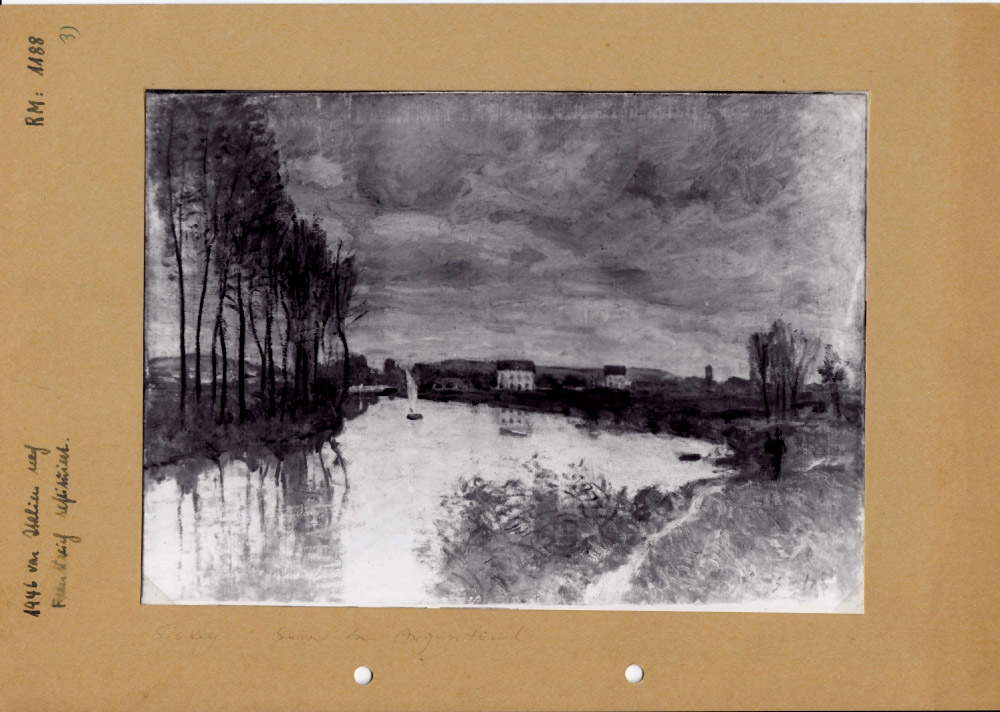

| Alfred Sisley, La Seine à Argenteuil, photograph relating to the file of the work ceded by Goering to the Ventura, in Die Kunstsammlung Hermann Göring, database on-line. |

|

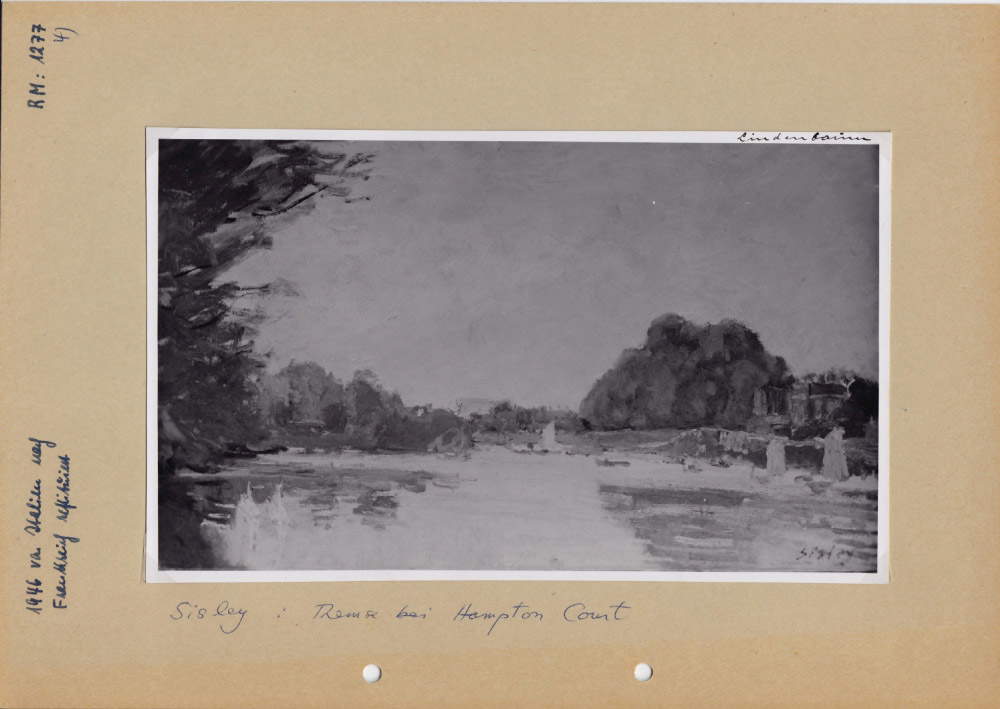

| Alfred Sisley, La Tamise à Hampton Court, photograph relating to the file of the work ceded by Goering to the Ventura, in Die Kunstsammlung Hermann Göring, database on-line. |

|

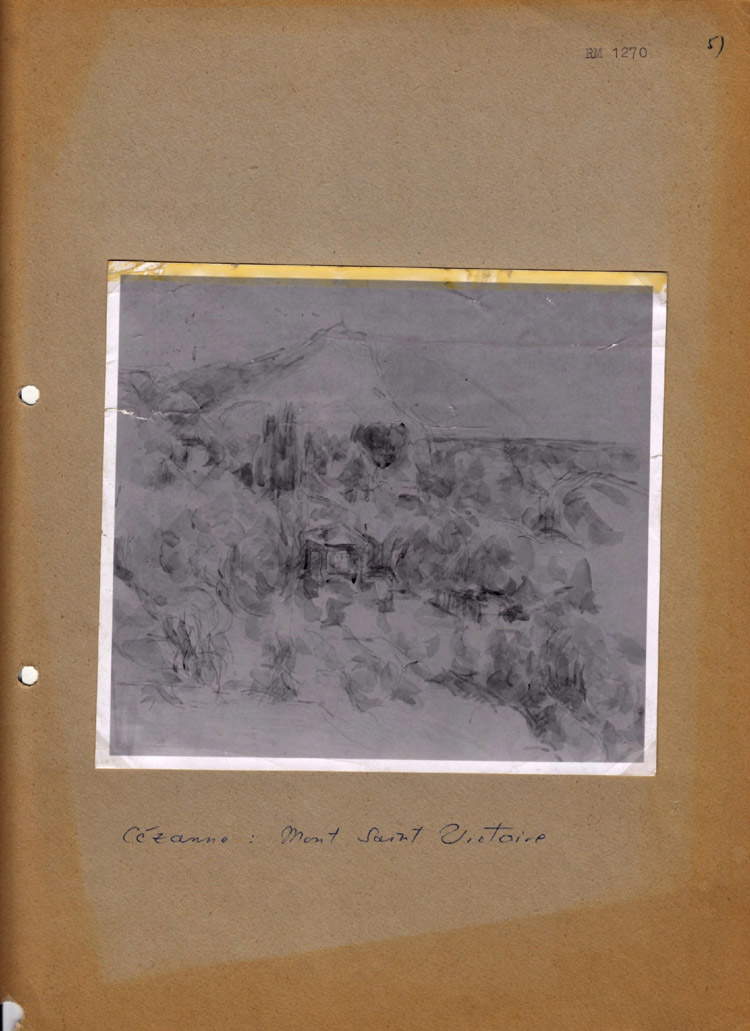

| Paul Cézanne, Mont Saint-Victoire, photograph relating to the file of the work ceded by Goering to Ventura, in Die Kunstsammlung Hermann Göring, database on-line. |

|

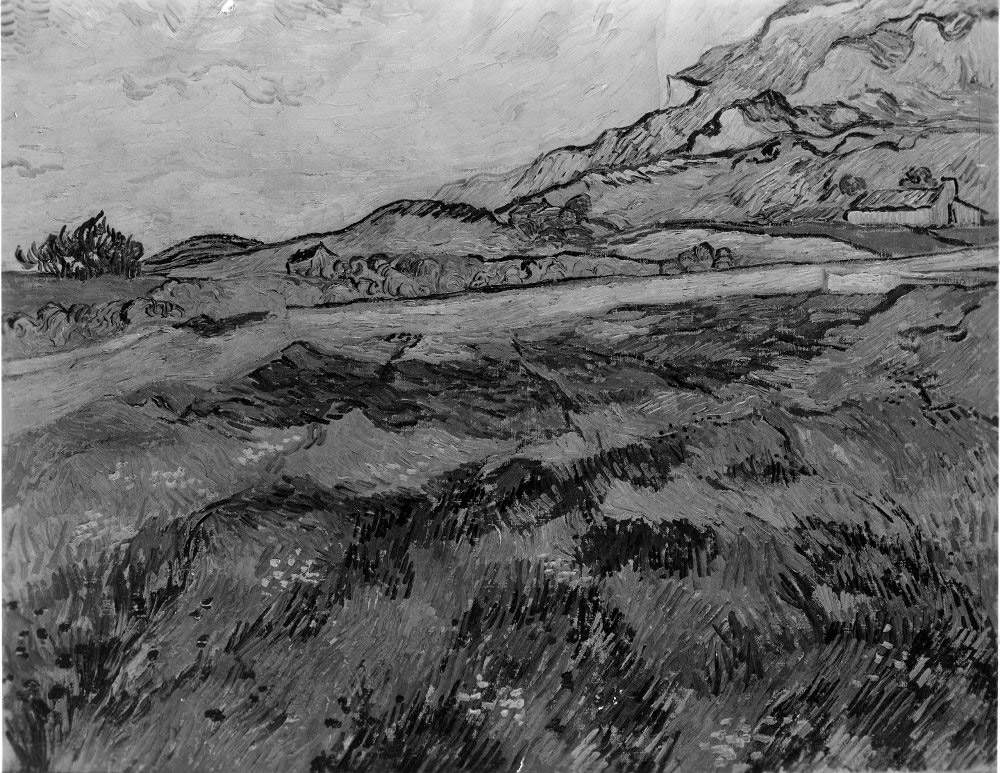

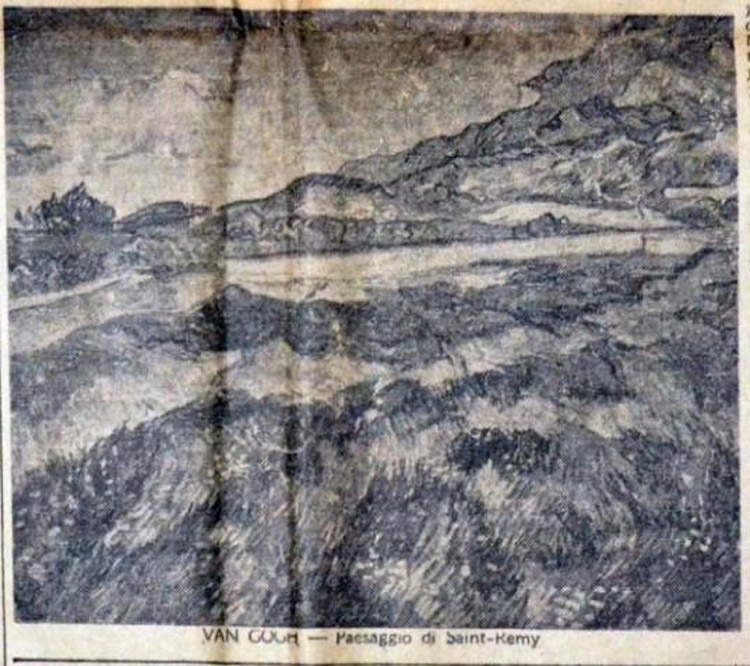

| Vincent van Gogh, Paysage à Saint-Remy, photograph related to the file of the work ceded by Goering to the Ventura, in Die Kunstsammlung Hermann Göring, database on-line. |

|

| Vincent van Gogh, Paysage à Saint-Remy, photograph published in La Nazione del Popolo, August 17, 1945, digitized from the newspaper preserved at the Rodolfo Siviero House Museum. |

The Italian works given by Ventura to Göring, on the other hand, were identified at the Collecting Point in Munich by the Italian Delegation for the Recovery of Works of Art, which left for Germany on Sept. 27, 1946. Once the nine works by Impressionist painters had been returned to the French government, and precisely in light of what the Italian government had done to make this happen, there was a strong demand from the Italian authorities for the return of the darte works still in Germany. But it was only thanks to the De Gasperi-Adenauer agreement of 1953 that the return was granted and the works physically returned to Italy in June 1954.

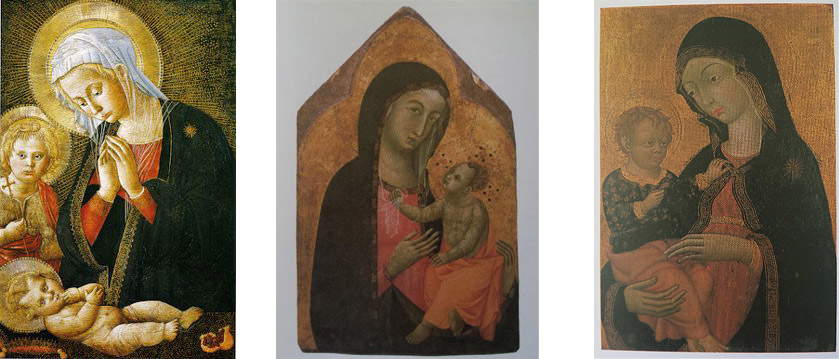

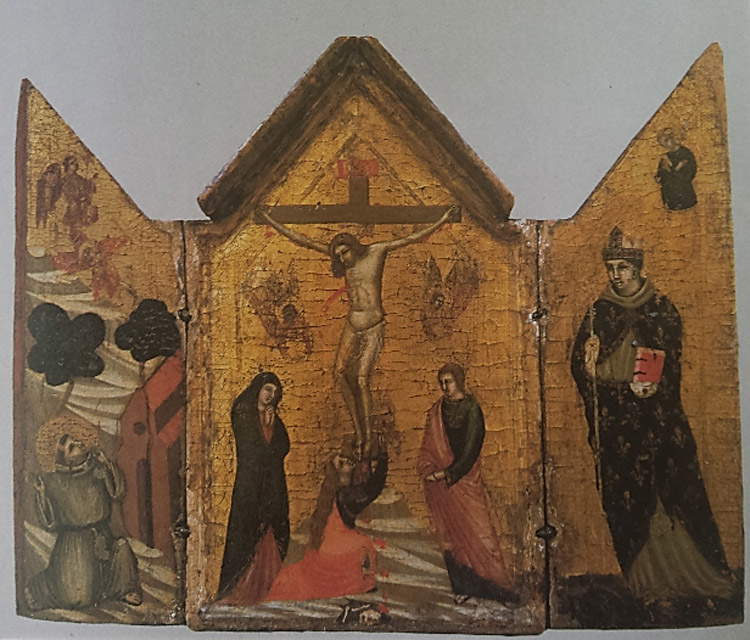

Finally, the works, once back in Italy, were returned to the city of Florence, from which they had come before being taken to Germany. From 1953 to 1988 they were part of that depository known as the Recupero Siviero, which was physically located in the Palazzo Vecchio. Then, but only between 1989 and 1990, destined for their current locations: the Uffizi Gallery and the Museum of Palazzo Davanzati.

|

| Left: Attributed to Pseudo Pier Francesco Fiorentino, Madonna in Adoration of the Infant Jesus with St. John the Bapt ist (second half 15th century; tempera on panel, 59 x 40.5 cm, Uffizi Gallery, Depot). Center: Master of Montemerano, Madonna and Child (first half 15th cent.; tempera on panel with gold ground, 57 x 39 cm; Uffizi Gallery, Deposit). Right: Master of San Torpè, Madonna and Child (early 14th cent.; tempera on panel with gold ground, 60 x 38.3 cm; Uffizi Gallery). |

|

| Bottega di Pacino di Bonaguida, Triptych of the Crucifixion with St. Mary Magdalene (central compartment), St. Francis (left compartment), St. Louis of Toulouse (right compartment) (first quarter of the 14th cent.; tempera on panel with gold leaf punched in, 39, 5 x 48, 5 cm; Uffizi Gallery, New Rooms of the Primitives). |

|

| Giovanni di Ser Giovanni known as lo Scheggia, Stories of Susanna (mid-15th cent.; tempera on panel, 41 x 127, 5 cm; Museo di Palazzo Davanzati). |

|

| Giovanni di Ser Giovanni known as lo Scheggia, Heroes Chosen by Fame (mid-15th cent.; tempera on panel, 44 x 85 cm; Museo di Palazzo Davanzati). Credit |

It is fitting, at this point, to conclude by opening a parenthesis on an affair collateral to the Ventura affair, but of no less importance.

|

| Copy from Sandro Botticelli, Cathedral Portrait (second half 15th century; oil on terracotta, 53 x 31.6 cm; Uffizi Gallery, Deposit). |

In June 1945 the article Antiques and Collaborationism was published in La Nazione del Popolo. In it it brought to light the network of relations, which the other great Florentine antiquarian, Contini-Bonacossi, had woven with Göring and his emissaries, so much so that he enjoyed the protection of the Gestapo and the S.S. And according to the author of the article it was the then Undersecretary of the General Directorate of Antiquities and Fine Arts, Carlo Ludovico Ragghianti, who had covered up and protected Contini. A few days later the Ventura case would break out. About a month later, another newspaper, LEpoca, published, on September 11, the article Justice in Slippers (More on the Goering-Ventura Affair), in which Ragghianti was accused of trying to stop the investigation into the Ventura scandal. Brought into the case by Ragghianti himself in a letter of protest to Repaci, editor of the newspaper, Siviero had stated that he had had the investigation of the Ventura Affair conducted by the Carabinieri, who had then questioned Ventura himself and other witnesses, but that he was in no way responsible for what the newspapers wrote. Ragghianti did not believe Siviero’s good faith. Hence the open clash between the two, which led to the opening of a parliamentary inquiry to verify the allegations against Ragghianti and the temporary suspension of Siviero from his position as Chief Recovery Office. Ragghianti was relieved of all charges and it was, therefore, deemed necessary to remove Siviero from his post. On the other hand, the still unsuccessful delivery of the Impressionist works to the French government and Siviero’s suspension risked blocking that delicate game of revenge on which the entire mechanism of restitutions marched. But it was undoubtedly the unexpected letter, dated October 2, 1945, from Admiral Ellery W. Stone to then Prime Minister Ferruccio Parri, that rescued Siviero from the bad situation he was in at the time.

Meanwhile, public opinion continued to take an interest in the affair and so, yet another newspaper article was published, Antiquari all’assassalto delle opere darte, which appeared on December 6, 1945 in Risorgimento Liberale. The fact that Ragghianti had Sandrino, the nephew of the well-known Florentine antiquarian, as his special secretary, gave the journalist of Risorgimento Liberale grounds to claim that, in addition to Ventura, Ragghianti was also protecting Contini. Ragghianti was, moreover, deliberately and publicly accused of calling for the suppression of the Ufficio Recuperi after the Ventura scandal broke out. In fact he made a request to the Ministry of Public Education as early as August 6, 1945; a request motivated by its lack of efficiency and the interference of the S.I.M. in the functioning of the offices dependent on this Ministry. But the Minister interrupted the process of transforming the Ufficio Recuperi, at the moment when the Ventura case broke out and in light of the decisive role that Siviero and his Office had precisely in the conduct of the investigations.

The controversy, which otherwise, in all likelihood, would have had even more unpleasant aftermaths, came to an end following the fall of the Parri government and the consequent resignation of Ragghianti. Thus, in the spring of 1946, Siviero, thanks to the favorable wind blowing in his favor after the new De Gasperi government and Enrico Molè took office at the Ministry of Education, was officially designated as head of the Ufficio recupero. And so it was that silence fell on the whole affair. Silence that seems to have been wanted by its protagonists themselves. Siviero, as if wishing to carry out a sort of damnatio memoriae, did not make the slightest explicit mention of Ragghianti, so when even much later he wrote about the Göring Ventura exchange, both in

For his part, Ragghianti did the same in his writings, alluding to the affair and the characters, without naming Siviero, as if to emphasize the appropriateness of the role that, in spite of everything, he found himself playing. It should be remembered that Siviero was not a qualified art historian, and his past in the SIM raised, and still raises, numerous doubts about his absolute probity. The fact remains, however, that Siviero remained head of the Ufficio Recuperi, despite numerous attempts to close it down, until his death. This was even though, for Ragghianti, Siviero, not meeting the necessary requirements, was probably not the man to carry out such a delicate task. A clash, that between Ragghianti and Siviero, which, at the end of the day, actually diverted the discourse toward issues not really relevant to the main one that, instead, the Ventura case had really raised: how to obtain the return of those works that the Nazis, in particular Marshal Göring, had indeed illegally exported from Italy to take to Germany, but with the collaboration and complacency of those Italian antiquarians, particularly Florentine ones, who had profited from the negotiations with the Nazis and from the exchanges or buying and selling of precious darte objects. This was a problem that was increasingly gaining ground in an Italy where laws to protect our cultural heritage existed (think of the Bottai Laws of 1939) but where the fascist regime and its corrupt bureaucratic machine had allowed them to be circumvented (see in this regard the striking case of the Lancillotti Disk, purchased by Hitler with the complacency of Ciano and Mussolini, later recovered by Siviero himself in 1948). Dynamics, these, that allowed, in the years around World War II, an exodus of countless works from our country. Many of them, thanks also to the work of people like Siviero, have fortunately returned to be part of the cultural fabric that produced them, to which they bear witness and where it is right, from an art historical and documentary point of view, that they be preserved and appropriately protected.

Reference bibliography

- Eike Schmidt, Fabrizio Paolucci, Daniela Parenti, Francesca De Luca (eds.), La Tutela Tricolore.

- The Guardians of Cultural Identity, exhibition catalog, (Florence, Gallerie degli Uffizi, Aula Magliabechiana, December 20, 2016 to February 14, 2017), Sillabe, 2016

- Commission des archives diplomatiques, Le Catalogue Goering, Edition Flammarion, 2015

- Corinne Bouchoux, Rose Valland :

- resistance at the museum, Laurel Publishing, LLC, 2013

- Francesca Bottari, Rodolfo Siviero, Castelvecchi editore, 2013

- Monica Naldi, Emanuele Pellegrini (eds.), Carlo Ludovico Ragghianti: the value of cultural heritage .

- Writings from 1935 to 1987, preface by Donata Levi, Felici editore, 2010

- Federica Rovati, Il recupero delle opere darte trafugate dai tedeschi, Annali della Facoltà di Lettere e Filosofia dellUniversità degli Studi di Milano, volume LVIII, fascicolo III, September - December 2005, pp.

- 266 291

- Ministero degli Affari Esteri, Ministero per i Beni Culturali e Ambientali, LOpera da Ritrovare, Repertorio del Patrimonio Artistico italiano disperso allepoca della Seconda guerra mondiale, Rome, Istituto Poligrafico e Zecca dello Stato, 1995

- Beatrice Paolozzi Strozzi, Fiorenza Scalia (ed.) Lopera ritrovata: A

- Tribute to Rodolfo Siviero, Florence ,

- exhibition catalog (Florence, Palazzo Vecchio, from June 29, 1984), Cantini Edizioni darte , 1984

- Rodolfo Siviero, Larte and Nazism, Florence, Cantini editore, 1984

In addition to the above texts, reference was made to the extensive documentation produced following the outbreak of the Ventura case and currently preserved in the following archival funds:

- Siviero Archives, Museo di Casa Siviero, Florence, Fondo Stampa quotidiana e riviste periodiche

- Siviero Archives, Rome, Busta 35, Pratica3/427

- Fondazione Centro Studi sullArte Licia and Carlo Ludovico Ragghianti, Ragghianti Archives, Lucca, Busta Sottosegretariato Reparto calunnie 1945-1965 (Siviero), Fascicoli Reparto Calunnie I and Reparto Calunnie II

- Archivio Centrale dello Stato, Rome, Fondo della Direzione Generale delle Antichità e Belle Arti, Divisione III, 1929-60, 1929-60, Envelope No. 147, 1938/55, Classification 4 Florence, Exhibitions and Recoveries: Florence, French Paintings Recovered at lantiquario Eugenio Ventura, Envelope No. 178, 1940/50, Classification 4 Rome, Exhibitions: Rome 1946 1947 1948, Palazzo Venezia, Mostra darte Francese

- Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Paris, Base Spoliations, Carton 377.98, Cote P8 Italie, recherche doeuvres dart dorigine française, 1940-1950, Fascicoli Italie Affaire Ventura. Correspondance 1945-1948 and Italie Exposition à Rome 9 tableaux impressionnistes hidden by Ventura 1946-1947.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.