An extraordinary episode of Franciscan art in Siena: the cycle of Pietro and Ambrogio Lorenzetti

Inside the Basilica of St. Francis in Siena, in two side chapels of the left transept, are three large wall paintings that, together with a few other fragments that are currently in the museum, are the precious evidence of what remains of the cycle created by Pietro and Ambrogio Lorenzetti in the chapter house of the adjoining Franciscan convent. They were discovered fortuitously under a layer of drapery shortly after the mid-19th century, in a room that was used as a blacksmith’s workshop at the time, and were immediately judged to be of great value and interest. The former Franciscan convent was about to be converted into the new bishop’s seminary (in particular, the old chapter house was to become the new refectory), so it was decided to remove those paintings and move them to the church. The technique used for the three large depictions was that of mass detachment, that is, a portion of the wall behind was removed in addition to the painted surface.

Given the large size of the figurations to be removed, it was considered such a significant intervention that it was taken as an example in Ulysses Forni’s Manual of the Restorative Painter in 1866. With this operation the Crucifixion, later placed on the left wall of the Piccolomini d’Aragona Todeschini chapel, the Martyrdom of the Franciscans and the Public Profession of St. Louis of Toulouse, placed instead, in the Bandini chapel, facing each other, were detached. The figure of a Resurrected Christ was also initially detached in solids, but left inside that room, which became a refectory, placed above the entrance door. It was torn off only in 1970 and, after temporary storage in the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, found its final location in the Diocesan Museum of Sacred Art, where a frame fragment depicting within a hexagon King Solomon is also preserved of this cycle. Other fragments took the path of collecting primitives since the second half of the 19th century and are now preserved in the National Gallery in London. These are a beautiful fragment depicting Heads of Poor Clares, a Mourning Virgin and a Saint Elizabeth of Hungary . There is also a further fragment, first identified by Max Seidel, possibly also attributable to this cycle: it is a Franciscan Head currently in the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery.

At first it was mistakenly believed that the frescoes found were those described by Lorenzo Ghiberti in his Commentari, in which instead was described the cycle painted by Ambrose alone for the cloister, also in the Franciscan convent in Siena. Unfortunately, of this other cycle, so praised by Ghiberti in his own text, only two fragments remain, preserved in the rectory of the University of Siena.

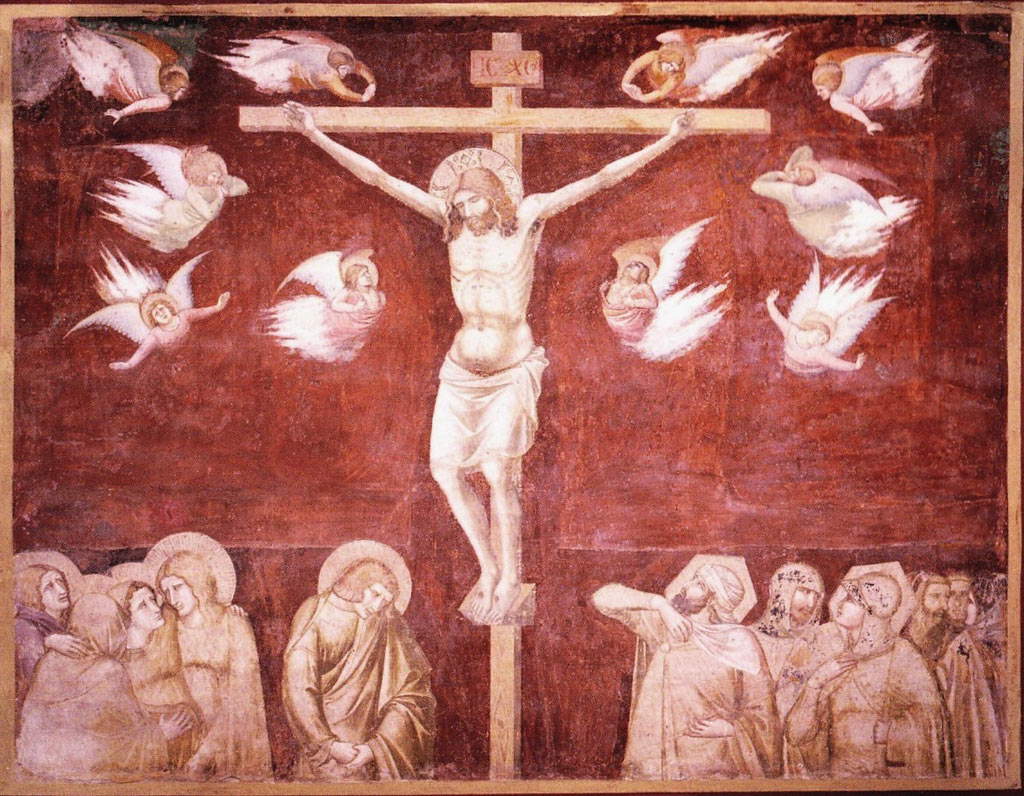

|

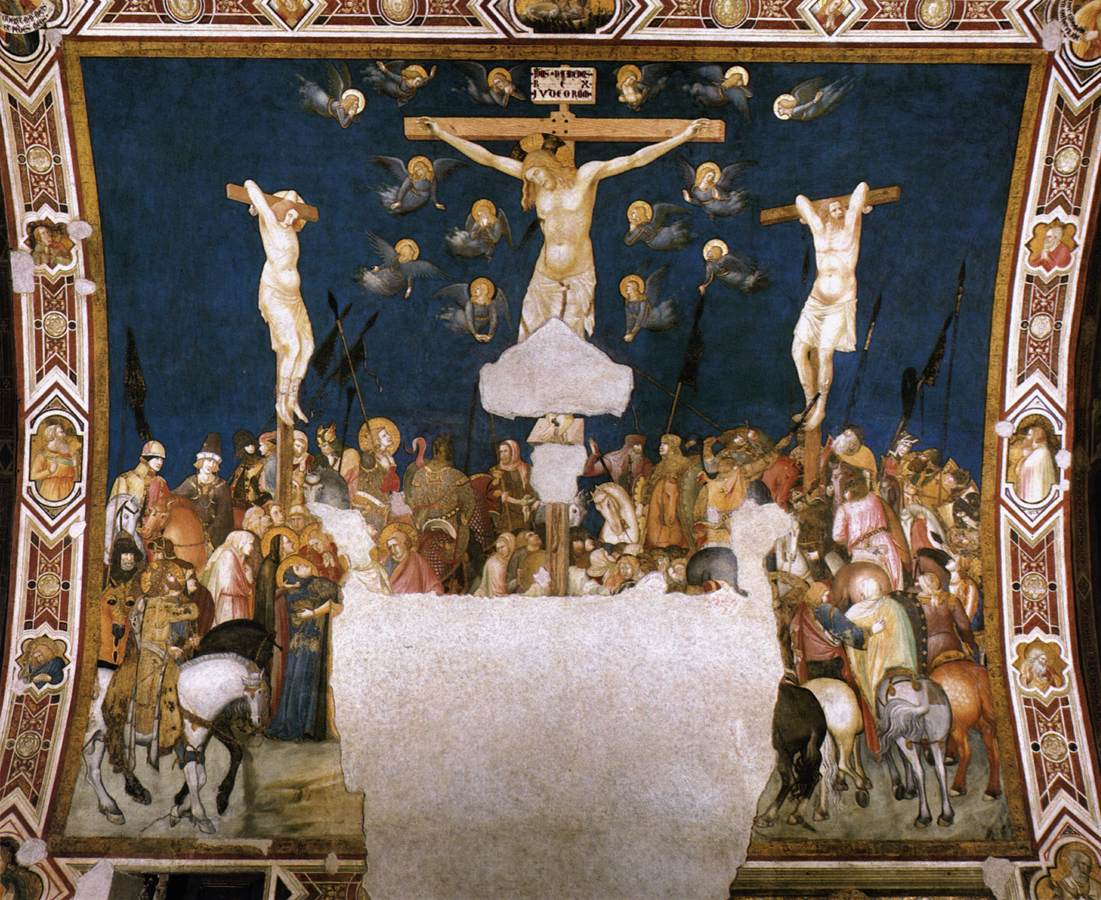

| Pietro Lorenzetti, Crucifixion (early 1420s; fresco; Siena, Basilica of San Francesco) |

|

| Pietro Lorenzetti, Risen Christ (early 1420s; fresco; Siena, Museo Diocesano di Arte Sacra) |

|

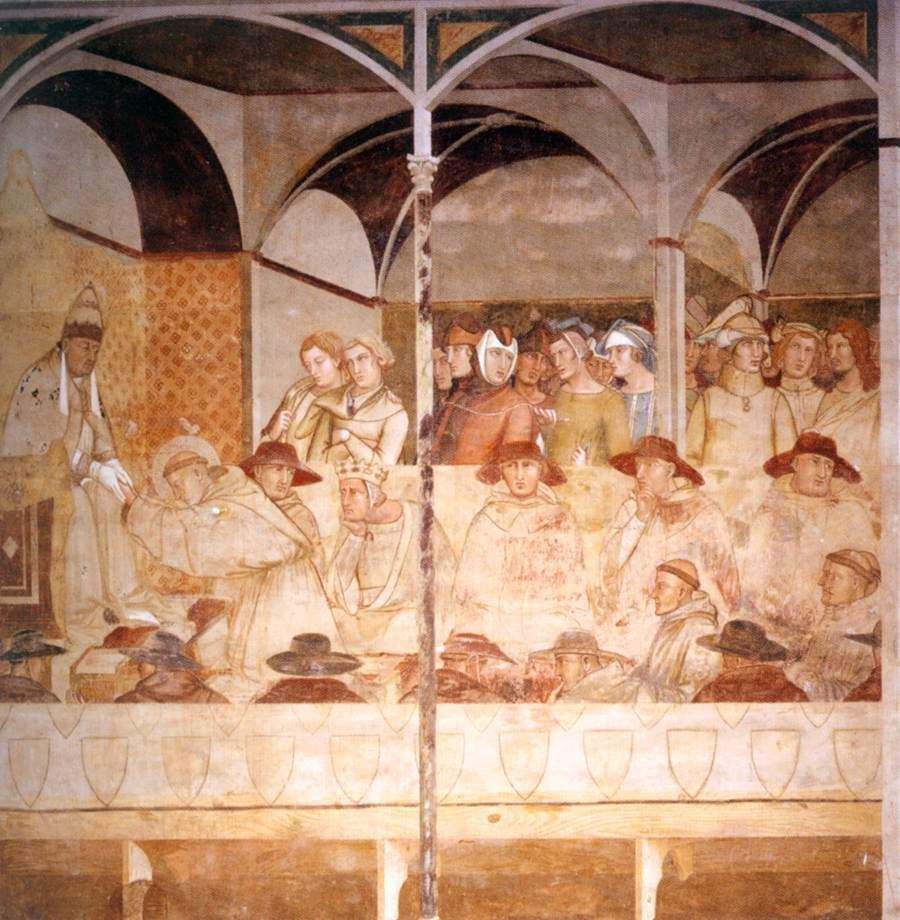

| Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Martyrdom of the Franciscans (early 1420s; fresco; Siena, Basilica of San Francesco) |

|

| Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Public Profession of St. Louis of Toulouse (early 1420s; fresco; Siena, Basilica of St. Francis) |

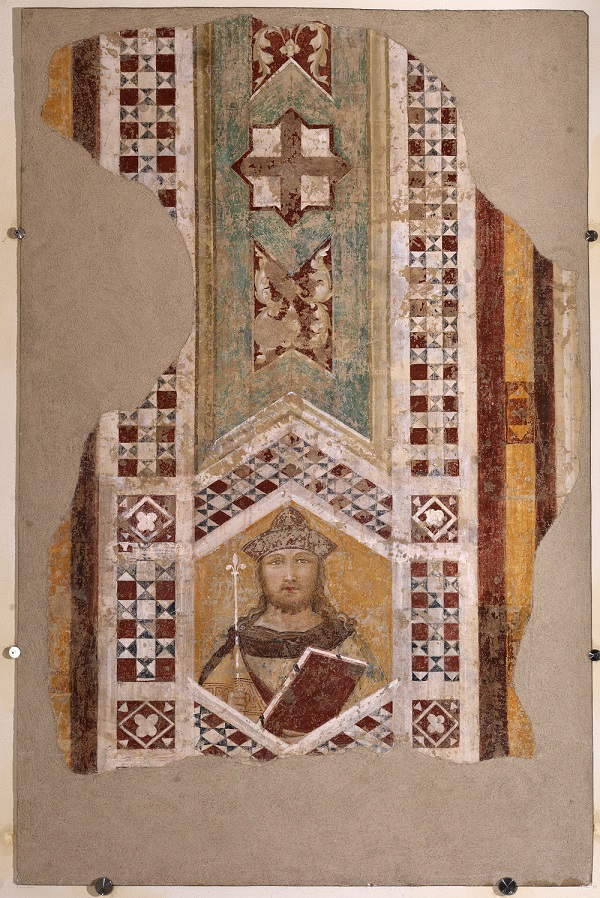

The Crucifixion and Risen Christ, found on the eastern wall, the one opposite the original entrance, can be attributed to the hand of the elder of the two brothers, Pietro, to whom the fragments of the Sorrowful Virgin and Saint Elizabeth are also attributed. To Ambrose, on the other hand, are attributed the two large narrative scenes found on the right wall, the Heads of Clarisse and King Solomon.

To understand the iconographic choices of this cycle, one must first consider that the chapter house was the second most important place, after the church, within a convent complex: it represented the decision-making heart of the convent and the place where illustrious guests who came there were welcomed. It therefore became necessary to devise specific iconographic choices for these rooms. In the case of the chapter rooms of the mendicant orders, on the back wall was an indispensable presence, drawn from monastic tradition, the Crucifixion, frequently flanked by scenes related to the Passion and Resurrection of Christ, while on the other walls the narrative element was developed, with the intention of illustrating episodes from the life of the holy founder of the order or significant events related to the order. In the Franciscan chapter of Siena one finds precisely these iconographic needs. The Risen Christ was in fact found on the same wall as the Crucifixion. This risen Christ represents an iconographic novelty: indeed, there are no known previous depictions in which Christ is standing in front of the door of the tomb, advancing with foot and holding the banner of the Resurrection. There are several subsequent attestations of the fortune of this iconographic model in the Sienese context.

The Crucifixion is dominated by the cross of Christ in a central position, while the bystanders are neatly positioned at the sides, without any confusing effect. Starting from the left, one recognizes the group of pious women supporting the Virgin and Saint John in mourning. They seem almost all restrained in expressing their grief; no exaggerated reactions are found. The figure of Christ on the cross is also composed. On the opposite side, the centurion, Longinus, another soldier, and a group of members of the sanhedrin are depicted. The centurion and Longinus have hexagonal nimbuses: at the time of the event depicted, those characters had not yet converted. At the top of the composition the real dramatic explosion takes place, with the depiction of ten angels in an attitude of sorrow, fresh from their Assyrian memories.

Ambrose was instead responsible for painting the two large narrative figurations concerning events in the Franciscan order.

|

| Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Heads of Poor Clares (early 1420s; detached fresco, 70.4 x 63.4 cm; London, National Gallery) |

|

| Ambrogio Lorenzetti, King Solomon, (early 1420s; detached and applied fresco on fiberglass support, 133 x 93 cm; Siena, Museo Diocesano di Arte Sacra) |

|

| Pietro Lorenzetti, Sorrowful Virgin (early 1420s; detached fresco, 39 x 30 cm; London, National Gallery) |

|

| Pietro Lorenzetti, Saint Elizabeth of Hungary (early 1420s; detached fresco, 38 x 33 cm; London, National Gallery) |

In order to correctly identify the scene concerning Saint Ludovico and his public profession, it is necessary to pay attention to the individual characters present and the relationships between them. Starting with the protagonist of the story, Ludovico is kneeling before the pope and wearing only the Franciscan robe, no attribute of the bishop’s dignity is yet present (Ludovico, a member of the Angevin family, would later be appointed bishop of Toulouse). He makes a specific gesture toward the pontiff: he places his joined hands within those of St. Peter’s successor. This specific gesture echoes the tradition of feudal homage and vassalage relations. Other figures are also characterized by precise gestures. On the cardinals’ bench, one character with a crown can be spotted: it is Ludwig’s father, King Charles II of Anjou, holding his chin with one hand, codified as a ’gesture of meditation.’ He was adamantly opposed to his eldest son’s choice to renounce succession to the throne to enter the Franciscan order: in his expression one can read all his despondency! Another character, another gesture: among the crowd a young man, wearing the same veiled cap worn by the Angevin ruler, points to himself with his right hand. His mouth is half-closed: astonishment, perhaps even a bit of concern. These are elements that lead us to think that he is Robert, brother of Ludovico, who would become the new Angevin heir. Already from these passages we recognize Ambrose’s extraordinary attention to detail. Unfortunately, in some parts of the pictorial surface, such as on the heraldry present on the cloth covering the structure of the bench in the foreground of which only the outlines remain, the finishes were made in tempera and are no longer legible, because they have fallen off. Looking closely, one notices the great amount of detail that Ambrose gives to his depiction: hints of beards on the faces of some of the cardinals and the pope himself, the aforementioned bonnets on the heads of the royal family, painted with an incredible sense of transparency, the irises of some of the figures, which reveal some beautiful blue eyes. Another extraordinary aspect of this composition is the mastery of the spatial element that Ambrose demonstrates. He takes an important step forward compared to Giotto and Simone Martini: in fact, the artist depicts only the interior and not also the exterior of the environment he intends to represent. This ability of ’perspective interpretation’ also emerges from certain details: observe, for example, the trilobes carved into the supports of the bench, the carpet covering the step where the papal chair is placed, or the central column that divides the room.

The other major narrative scene concerns a martyrdom of Franciscans. The composition is dominated by a three-bay loggia with ogival arches, under which stand the sovereign who ordered the execution of the friars and his court. Three friars have already been martyred, and they have haloes, while three others are about to be executed and the sign of sanctity is about to appear on their heads. One of the severed heads is depicted in a skillful foreshortening. Ambrose’s descriptive ability is perhaps even more evident in this scene: he is in fact depicting a vast sampling of physiognomies and costumes. Another extremely interesting aspect is the extensive use of metal foils applied to the surface not only to make the soldiers’ armor, as Peter had already done in the Crucifixion, but also for the sovereign’s robe. In this case he did not want to reproduce the metal, but to create another effect in the fabric. This is an expedient used by Simone Martini in his Majesty in the Palazzo Pubblico, and Ambrose fits right into the groove of this polymathism.

It has not yet been possible to identify with certainty the martyrdom reproduced in the Sienese chapter. One of the most frequently advanced hypotheses, namely that it might be the martyrdom that took place in Ceuta in 1227, has to be discarded because seven friars were martyred on that occasion, while only six are depicted here. Proposals to identify it with some martyrdoms that occurred in the East are inconsistent with the chronology that is proposed for this cycle.

The fragment with the heads of the Poor Clares will provide valuable indications for trying to reconstruct the entire iconographic cycle in this room. Coming from the left wall of the chapter house, it belonged to a larger narrative scene. The currently most convincing hypothesis, which emerges from iconographic comparison with some representations also attested in the Tuscan context, is that it was part of a scene depicting St. Francis delivering the rule to the male and female orders.

|

| Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Martyrdom of the Franciscans, detail |

|

| Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Martyrdom of the Franciscans, detail. Ph. Credit Francesco Bini |

|

| Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Martyrdom of the Franciscans, detail. Ph. Credit Francesco Bini |

|

| Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Martyrdom of the Franciscans, detail. Ph. Credit Francesco Bini |

|

| Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Public Profession of Saint Louis of Toulouse, detail. Ph. Credit Francesco Bini |

|

| Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Public Profession of St. Ludwig of Toulouse, detail. Ph. Credit Francesco Bini |

|

| Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Public Profession of St. Ludwig of Toulouse, detail. Ph. Credit Francesco Bini |

|

| Pietro Lorenzetti, Crucifixion (c. 1310-1320; fresco; Assisi, Basilica of St. Francis) |

|

| Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Madonna and Child Enthroned (1319; tempera and gold on panel, 148.5 x 78 cm; San Casciano in Val di Pesa, Museo dArte Sacra Giuliano Ghelli) |

With the identification of these scenes and through comparison with other 14th-century Franciscan chapter rooms, in the volume Ambrogio Lorenzetti published on the occasion of the exhibition dedicated to the Sienese artist in 2017, I proposed a hypothesis for reconstructing the iconographic cycle of the Sienese Franciscan chapter.

On the back wall, one has to imagine a tripartition: in the center the Crucifixion, on the right the Resurrection (of which the fragment of the Risen Christ remains), and on the left a scene taken from the Passion (e.g., the Going to Calvary or the Flagellation). Continuing on the right wall, the Public Profession of St. Louis of Toulouse was positioned, followed by the Martyrdom of Franciscans. A scene of a martyrdom of Franciscans is also found depicted in the Chapter of the Basilica del Santo in Padua. In that context, it is correlated with the episode of the Stigmata of St. Francis. St. Francis had repeatedly sought martyrdom among the infidels, without ever succeeding, because God had reserved for him another kind of martyrdom: that of receiving imprinted in the flesh the marks of Christ’s cross. In Franciscanism, therefore, a parallelism is created between the stigmatization of St. Francis and the Franciscan friars’ vocation to martyrdom, reported in images in the chapter on the Saint. It is conceivable that this choice was also made in the Sienese cycle. In no other chapter house, however, is a scene concerning Saint Ludovico attested. What, then, was intended to be expressed by the depiction of this particular episode? At this point it must be considered that the fragment of the Poor Clares and the scene to which it belonged was placed in front of that of Saint Ludovic. The connection between the two scenes is less immediate than that of martyrdom and the stigmata. What unites them is the theme of obedience, one of the three Franciscan vows along with poverty and chastity. Indeed, Ludovico’s gesture toward the pope is a gesture of obedience, as is that of the Franciscans and Poor Clares toward the rule delivered by St. Francis. The need to value and emphasize this precise aspect of one’s vocational choice stems from the particular historical moment. The Franciscan order had faced the storm of the spirituals, that is, that part of the friars who were radically faithful to the founder’s rule and will. The very trial against the Tuscan spirituals was held in Siena. It is therefore safe to assume that the Sienese Franciscans, having experienced that situation at close quarters, wanted an emblematic episode of obedience to the pope to be depicted on the walls of their chapter, together with the delivery of the rule that represents the foundation for being able to live their Franciscan experience. Thus, the cycle was meant to serve as a constant reminder, in the decision-making heart of the convent, of one’s vow of obedience, to ward off new ’drifts,’ and one’s mission of evangelization without geographic boundaries, with the possibility of even arriving at martyrdom.

Regarding the chronology of this cycle, stylistic affinities can be found with the works created by Peter and Ambrose between the late 1910s and the first half of the 1420s. For Pietro, characters akin to the frescoes painted in the left transept of the Lower Basilica of St. Francis in Assisi are different. Another work that stands in fruitful comparison is the polyptych for the parish church of Santa Maria in Arezzo commissioned by Bishop Guido Tarlati in 1320, but completed within 1324-25. In Ambrose’s case, the preponderant use of a sharp, marked line to delineate the figures and the treatment of color to give a ’shiny’ surface brings the most significant comparison with the Madonna of Vico l’Abate dated 1319. These considerations lead one to place the making of this cycle in the early 1320s.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.