A famous library can still be the site of new and exciting discoveries, especially where the amount of material is so vast as to make it plausible that hitherto even unsuspected information could be found. This is what one might think upon learning of the extraordinary discovery involving the National Central Library of Florence where, from the manuscripts collection of historian Gino Capponi (Florence, 1792 - 1876), a re-emerged a corpus of drawings dating back to the 1610s and 1920s, traceable to the circle of the brothers Giuliano da Sangallo (Giuliano Giamberti; Florence, 1445 - 1516) and Antonio da Sangallo (Antonio Giamberti; Florence, 1455 - 1534), and depicting a number of monuments and buildings, real and invented, and predominantly Roman. Presented for the first time in an exhibition held at the library’s Sala Dante from July 7 to September 30, 2022, entitled Roma ritrovata. Unknown Drawings from the Sangallo Circle at the National Central Library of Florence and curated by Anna Rebecca Sartore, Arnold Nesselrath, Simona Mammana, and David Speranzi, the drawings represent one of the most significant finds in recent times for our knowledge of early sixteenth-century art and culture.

The importance of these twenty-seven architectural drawings, traced on six large sheets of parchment, measuring 495 by 395 millimeters, which have been given the name "Libro Capponi,“ lies, as the curators of the review at the National Central Library explain, in the fact that between the pages of this book appears what was to all intents and purposes the ”Rome pursued, reconstructed, fantasized about and dreamed of by the intellectuals, architects, artists and collectors who in theage of Humanism and the Renaissance contributed to renewing its myth, with pen and stone, studying, narrating and drawing it." Nesselrath called that of the Capponi Book a “spectacular discovery”: according to the German scholar, “in recent decades the Capponi Book is perhaps the most important contribution of unknown material concerning the study of antiquity.” The discovery, although published only this summer on the occasion of the exhibition, actually dates back to late 2018, when Sartore (now curator of the editio princeps of the drawings, published in the exhibition catalog) was working on her own research, on a completely different topic (as is often the case, relevant discoveries are often the result of chance encounters): the scholar, intrigued by a typewritten addition to the copy of the catalog of Gino Capponi’s manuscripts, had decided to open the manuscript “Gino Capponi 386,” the one that contained the drawings discovered. Sartore would later find that until then no one had studied those drawings.It therefore took more than three years of work to study the sheets found in the Capponi fund, to understand their context of origin, to understand what links they had with the culture of the time, and to attempt to formulate hypotheses about the sphere that had produced them.

One can speak, to all intents and purposes, of “forgotten papers,” as Sartore and Speranzi call these sheets, which in the Capponi Book appear as an adespota (i.e., without indication of the author’s name) and anepigraphic (lacking titles) series. The research started from an anonymous note dated June 3, 1905: “The Baron of Geymüller tells me that the architectural drawings in six sheets of parchment belonging to the Capponi house (of Via S. Sebastiano) seem to him to be by the hand of Antonio da Sangallo called the Elder-executed when he was a young man-and that it seems to him to be his writing what is seen in the sheet I marked [a blank space follows] and which says ’Santo Agnolo in Pescheria di Roma.’” We do not know who noted the attribution by the Swiss art historian Heinrich von Geymüller (Vienna, 1839 - Baden-Baden, 1909), but what is certain is that at the beginning of the 20th century someone viewed the drawings, without, however, leaving a trace in the studies (or so according to what we have been able to ascertain so far): after that, no one would ever put their hands on that material again. Sartore and Speranzi have tried to reconstruct, on the basis of the known information, the recent history of these sheets: they remained among the Capponi family’s material until 1905, the year in which they were still among the property of Marquis Folco Gentile Farinola, his great-grandson. The latter asked the “friend of Geymüller” (as the anonymous writer of the note was renamed) to study the contents of the six sheets of parchment, and the latter in turn asked the art historian for an expert opinion. “It is possible,” Sartore and Speranzi speculate, "that Farinola’s intention even then was to sell the drawings, which was postponed only for some time. In fact, in 1920 the entire Capponi palace was alienated to the Fabbri family, and ten years later the National Central Library of Florence purchased the autographs and correspondence of Gino Capponi and Giuseppe Giusti, as well as a small number of manuscripts of some importance. Among these was a ’roll’ of ’architectural drawings believed to be by Antonio da Sangallo,’ i.e. the Capponi Book." The book reportedly came to the Library in 1930 as a result of a purchase. The scrolls were summarily inventoried in 1989, but have never been studied.

The drawings were executed with a metal point, ruler and compass, and then reworked in pen and ink. Crucial to attributing them to the Sangallo circle was a comparison with the Codex Barberiniano, another set of sheets in which ancient monuments are illustrated that also return in the Capponi Book, and which are united by the use of the same graphic sources, moreover numerous. The Codex Barberiniano is one of the most important collections of drawings of the Renaissance: the sheets that comprise it were put together by Giuliano da Sangallo in the course of his career. There are, however, mainly conceptual differences that separate the author of the Capponi Book from Giuliano da Sangallo, above all, as Nesselrath explains, the fact that the former was much more technical and “architectural,” and the latter more “pictorial.” And again, “Giuliano da Sangallo’s actual architecture-pondered in the whole and refined in detail-is almost at odds,” Nesselrath explains, "with the boisterous romanticism of his studies from antiquity. From the Capponi Book and its Sangallesque variations some more rational intentions emerge and what seems to be a hermeneutic dynamic of such studies behind the scenes."

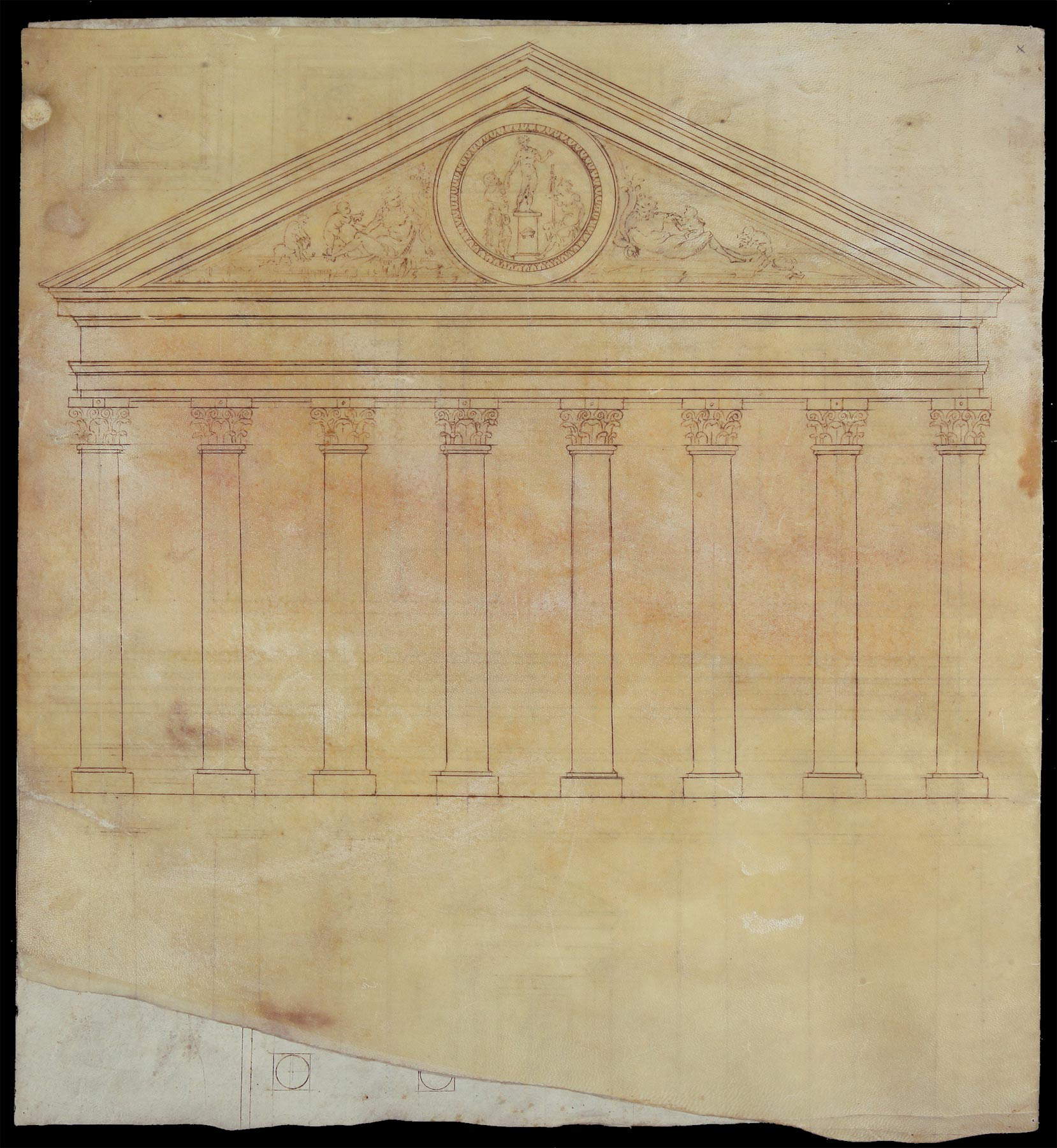

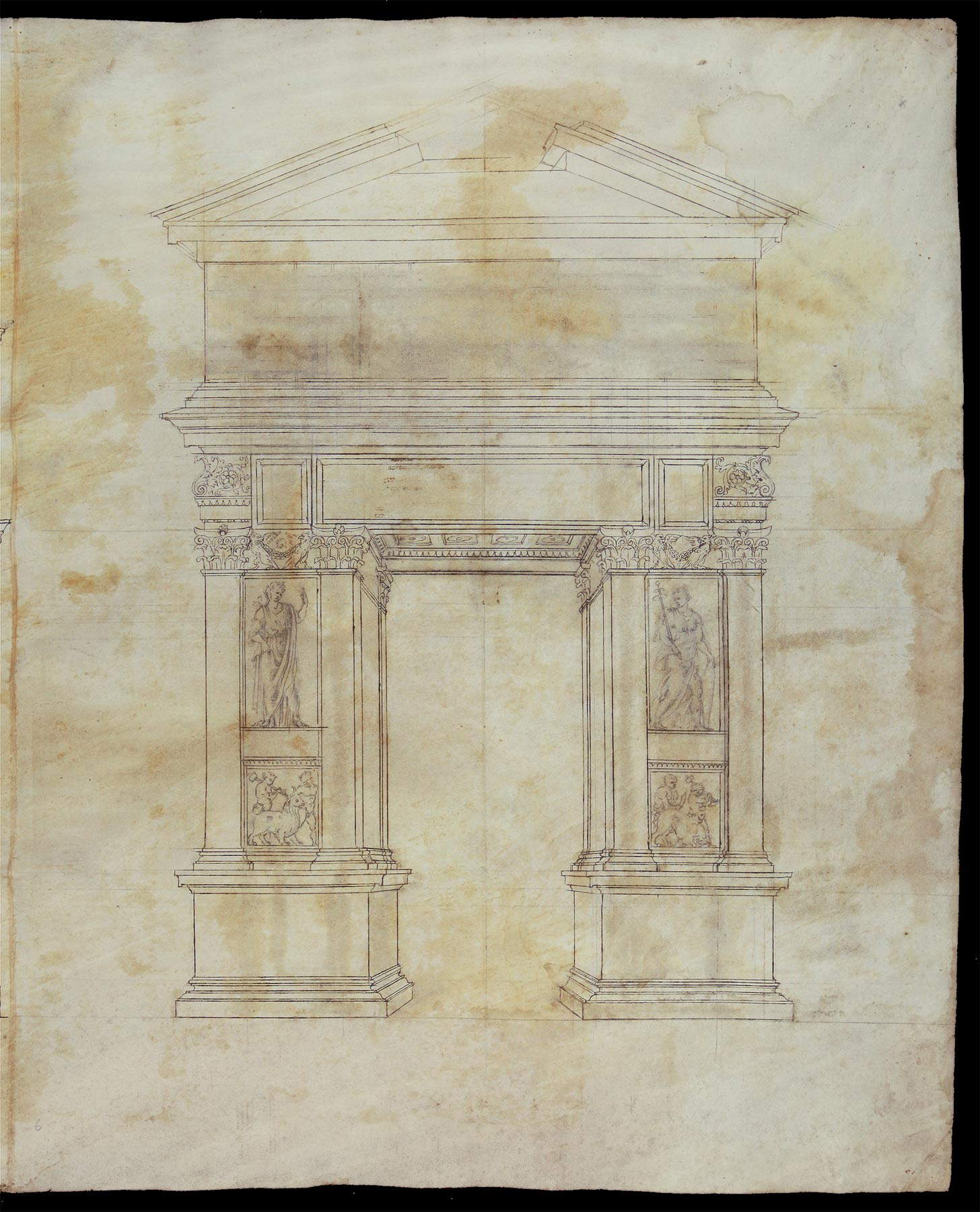

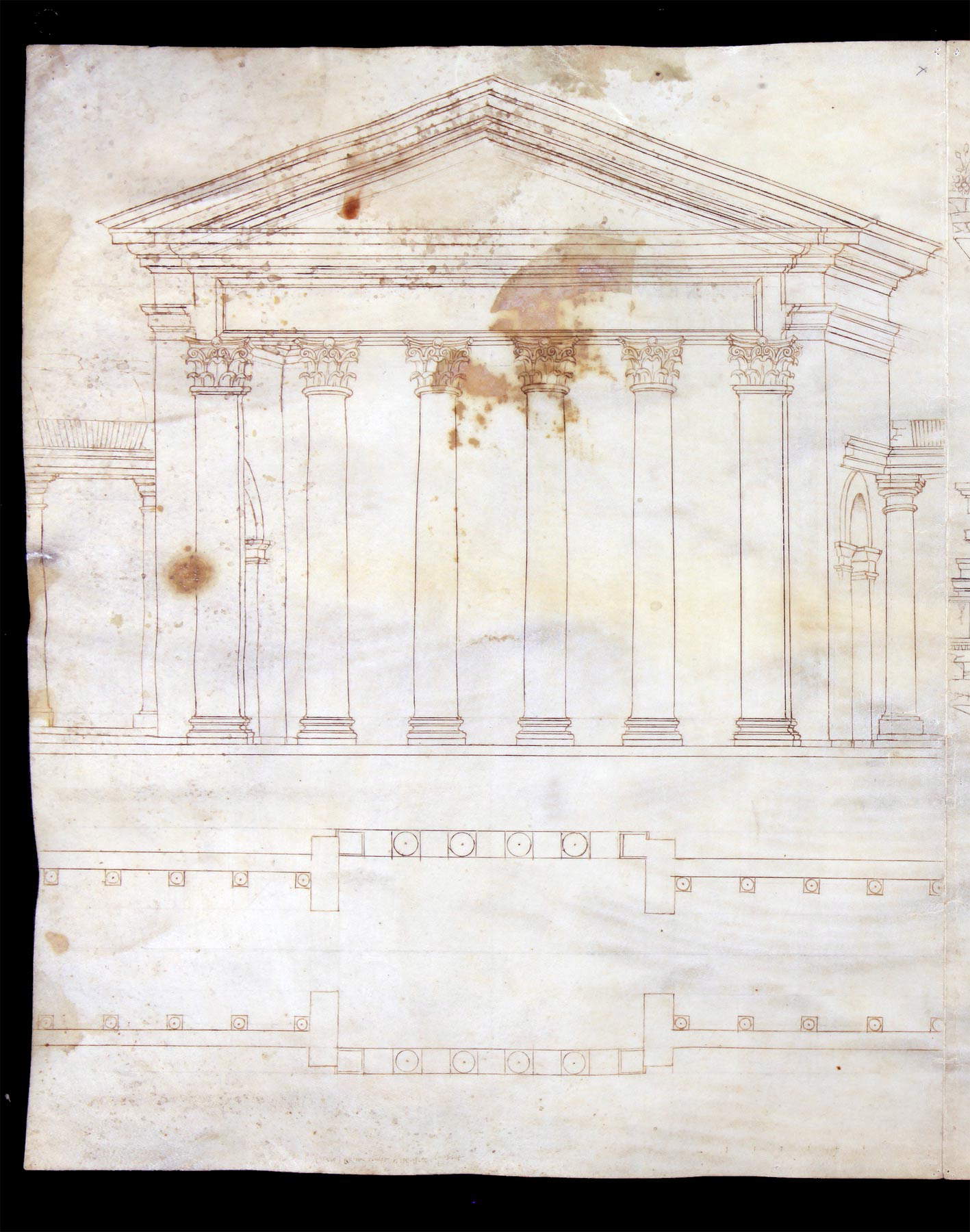

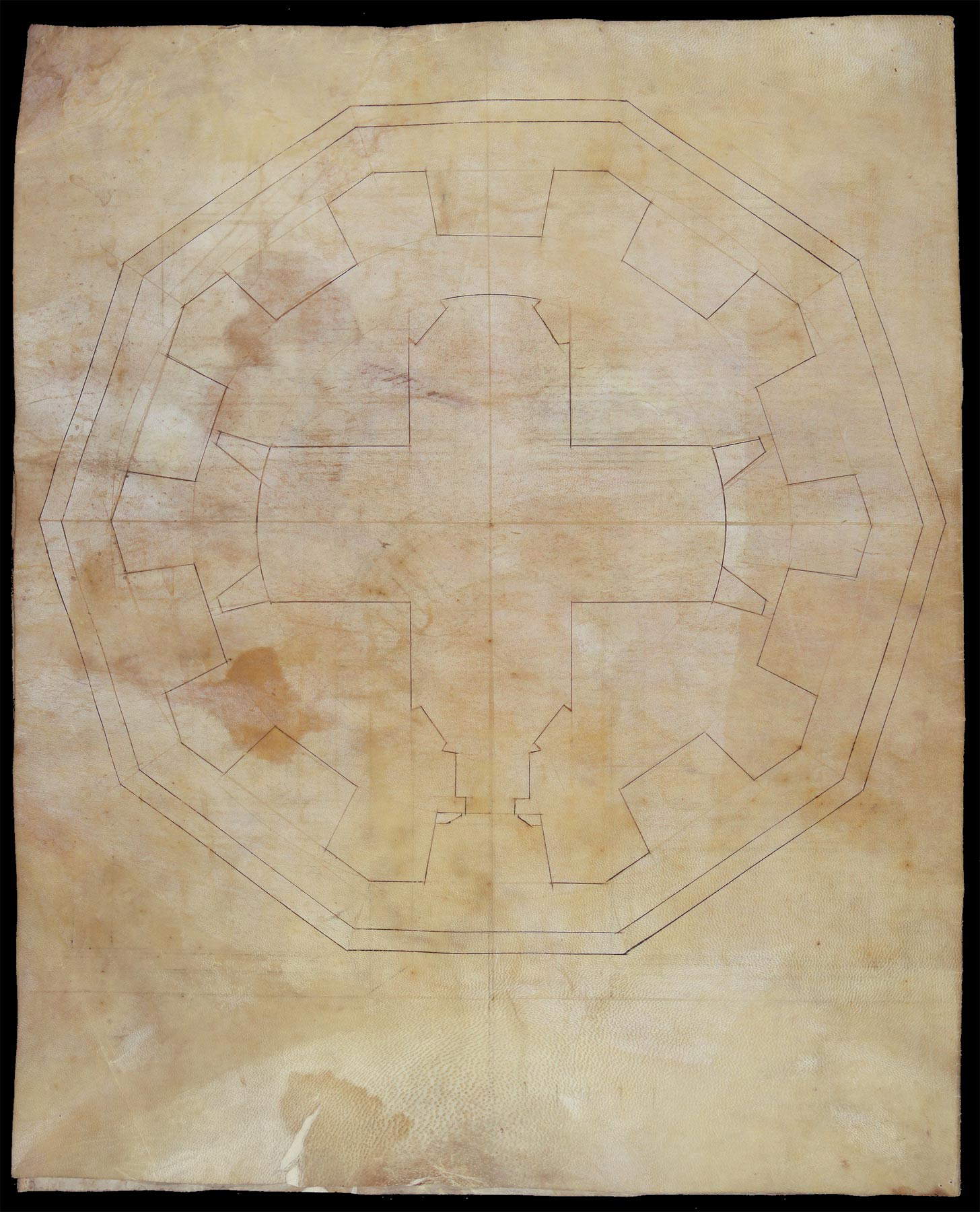

Impossible, here, to give an account of individual drawings: we have therefore opted for a selection of the most significant ones, starting with the plan of the Pantheon, a building with which all Renaissance architects had measured themselves. The drawing of the Capponi Book restores the interior and exterior of the Pantheon, without taking into account the superfetations that had occurred by the time the building was transformed into the church of Santa Maria ad Martyres (in 609 AD.): it is one of the many drawings compared with the corresponding one in the Barberiniano Codex, towards which it reveals some dependencies, a sign that theicnography (a term used to indicate a representation in orthogonal projection of the horizontal section of a building) present in the Capponi Book follows drawings available in the Sangallo workshop. Interesting is the drawing illustrating the front of an octastyle Corinthian temple (i.e., with eight columns) that so far has not been identified, perhaps inspired by the pronaos of the Pantheon: it is therefore a design of invention. In the tympanum we see in the center a large medallion on which the draughtsman has described a scene, and next to it are the figures of Tellus, goddess of the earth, and the god Ocean: probably the author of the drawing was inspired by some Roman sarcophagus with the representation of the seasons, since the figures of seasonal genii, such as those appearing between the figures of Tellus and Ocean, often go with these two deities. For the medallion, on the other hand, a modern source was followed, extensively revisited: the depiction is in fact taken from one of the tondi in the courtyard of the Medici Riccardi Palace, depicting Daedalus aided by Pasiphae as he adapts his wings to Icarus in the presence of Artemis, in turn inspired by a gem in ancient times in the Medici collections, now in the National Archaeological Museum in Naples. Another building of invention is thefour-fronted arch whose structure echoes that of the Arch of Janus at the Foro Boario, while the front draws on the Arch of Titus in Rome to that of Trajan at Benevento ( weeds also appear in the design, moreover). The work is also notable for the wealth of detail in which the draughtsman engaged, producing reliefs that allude to a triumphal iconography, with prisoners bound at the sides and, in the center, a battle scene between Romans and barbarians inspired, Sartore explains, by the "famous bas-relief in the Museum of the Ducal Palace in Mantua, which was in the collection of the Roman merchant Giovanni Ciampolini in the late 15th century and, later purchased by Giulio Romano, was sent to Mantua itself and used as a model for the fresco with The Death of Patroclus in the Hall of Troy in the Ducal Palace.“ the draughtsman could find the bas-relief reproduced in several drawing books available at the time. Another arch of invention, in which ”the ruinistic element becomes an expedient to present the monument" (so Sartore) is distinguished instead by the presence, inside one of the niches, of the Capitoline Pan that was much admired by artists and collectors in the early sixteenth century.

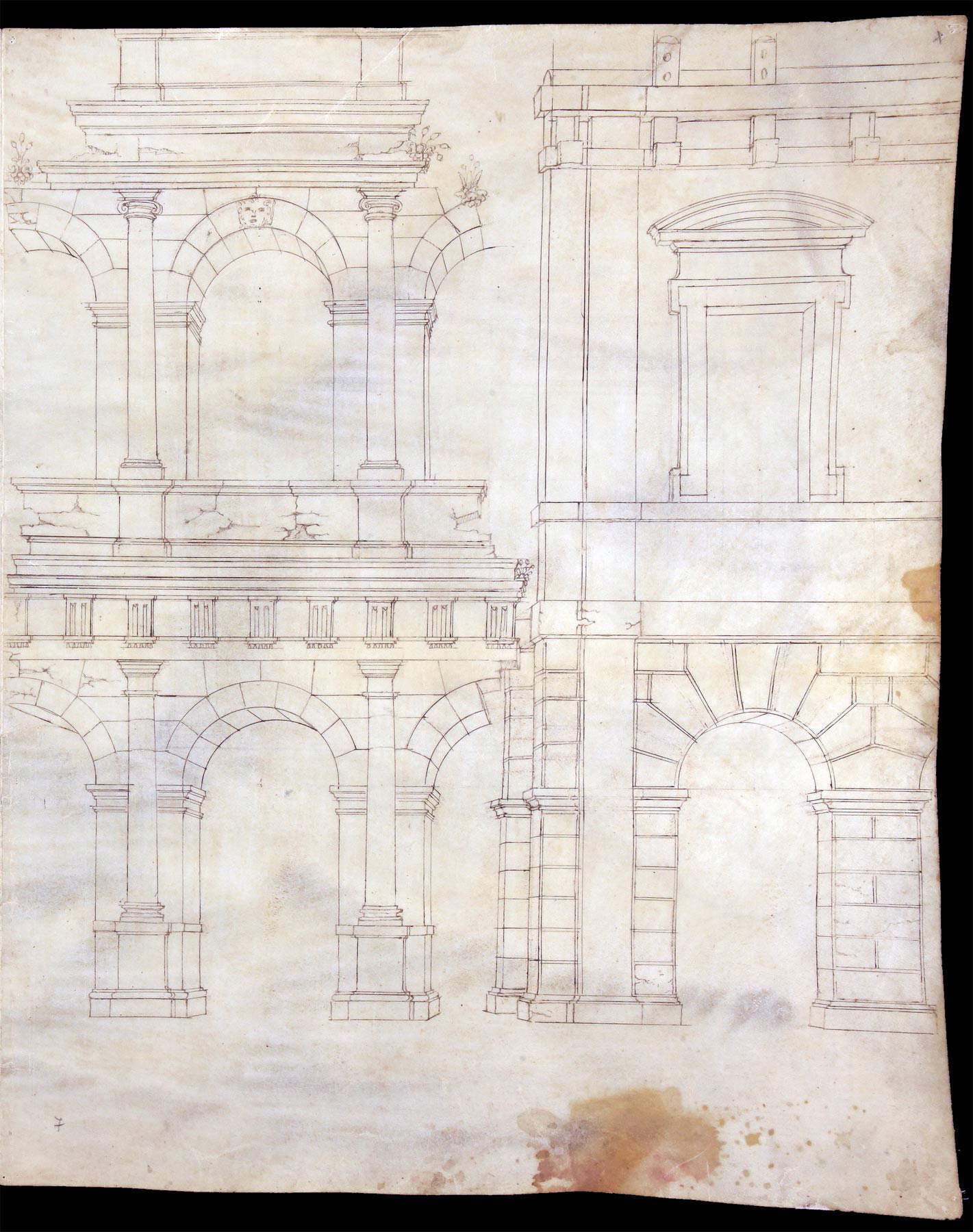

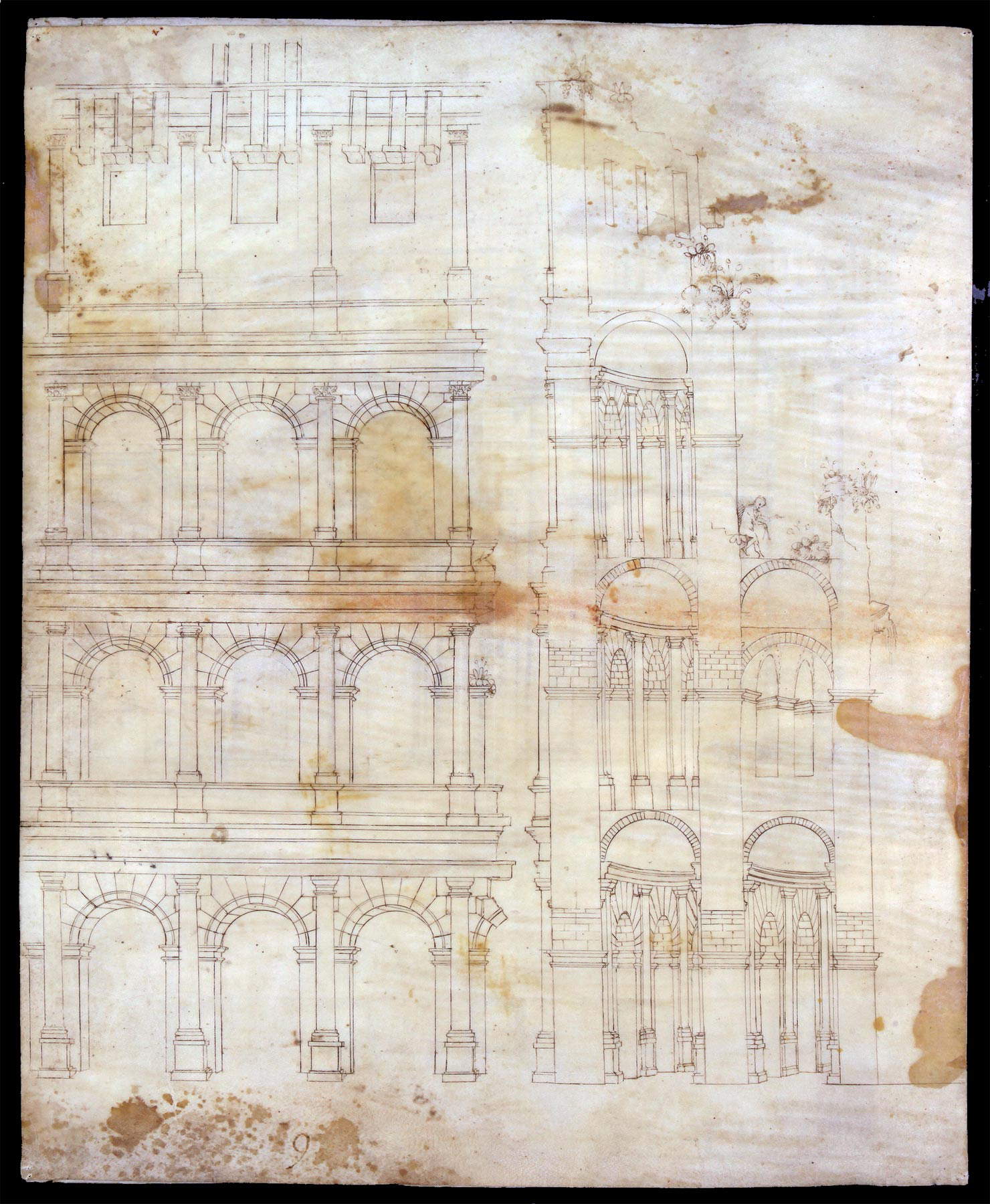

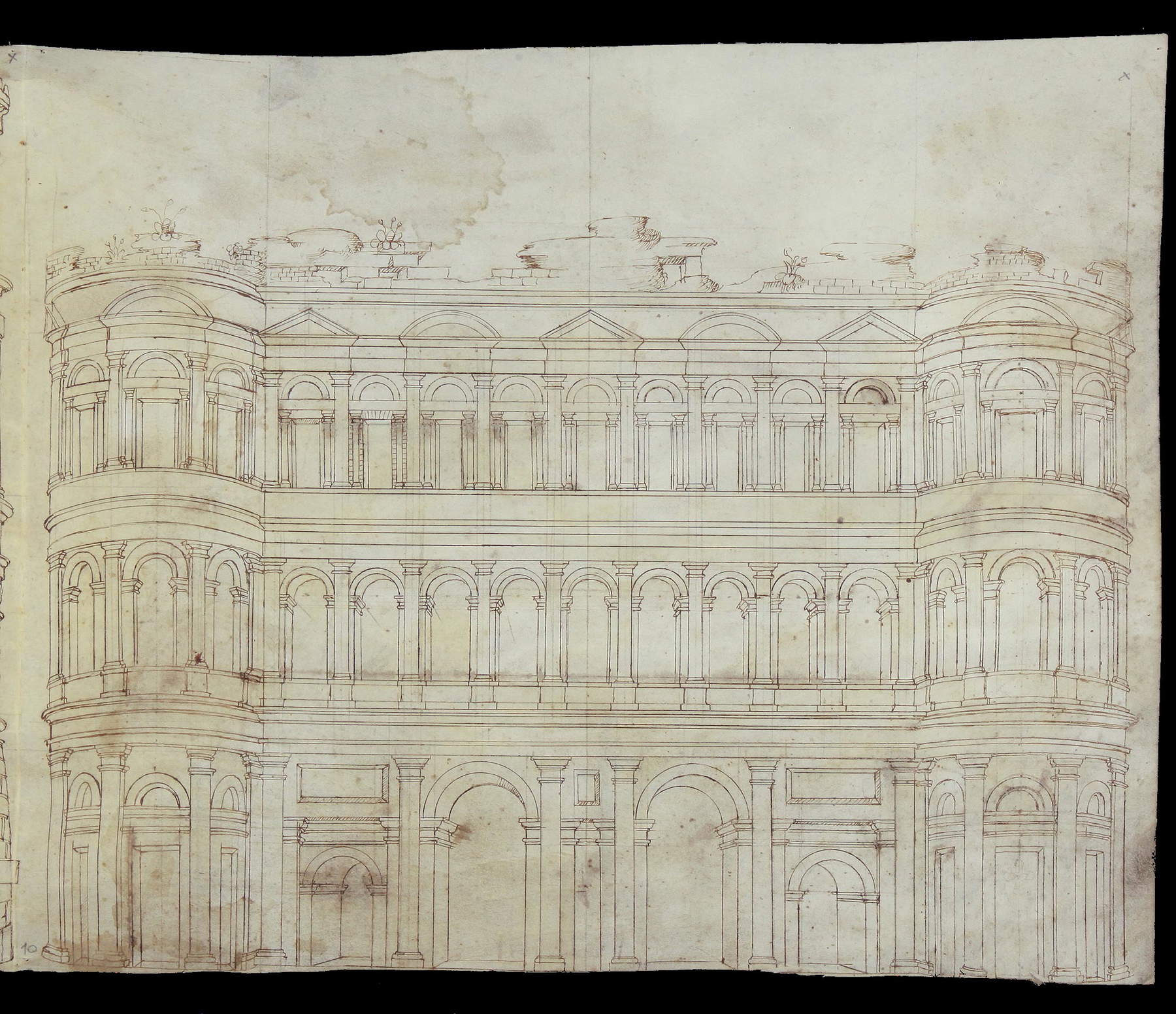

Among the royal buildings of Rome appears a drawing of theArch of the Argentari, which, as is often the case in the Capponi Book corpus (but the same applies to the Barberiniano Codex), proposes a full reconstruction. A reconstruction is also proposed for the portico of Octavia, while the draughtsman instead sticks to a more plausible situation by drawing the elevation of the Theater of Marcellus, which was already in ruins at the beginning of the sixteenth century, a condition alluded to by the weeds and cracks on its surfaces. It is therefore an interesting work to understand how this important building of ancient Rome, the theater dedicated between 13 and 11 B.C. to Marcus Claudius Marcellus, nephew of the emperor Augustus and designated by him as his heir (he died prematurely, however): we can see, for example, in the keystone of the second register one of the stage masks that had been placed to decorate the building, and which have disappeared today, but which in the Renaissance still stood in their place. Also present, finally, are two images of the Colosseum, in elevation and section, side by side: a monument that was much studied by Giuliano da Sangallo, who has left us numerous drawings of the Colosseum, in the Capponi Book it is reproduced in a drawing “of complex reading,” explains Sartore, for which “direct comparisons with the older sections in Giuliano’s codices cannot be established. Indeed, the depiction of the second ambulatory of the third order is missing just as the attic floor is not reconstructed where, without consistent use of perspective, only the three small rectangular windows are drawn. On the other hand, the effect of depth in the arcades of the annular corridors is hinted at, but without having a clear internal structure, and this is manifested in the way the prominence planes of the vaults are depicted.” The draughtsman again takes care to emphasize the ruined state of the ancient Flavian amphitheater, but at the same time he also intends to highlight the monument’s grandeur through the inclusion, in one of the third level windows, of a character who is taking a measurement with a compass, inserted for symbolic reasons (given the importance of the Colosseum) and perhaps also to suggest proportions.

With regard to monuments in other cities, it is worth noting the presence of a sheet with the elevation of a wall of the Baptistery of San Giovanni in Florence, which at the time was originally believed to be a temple dedicated to Mars: “The extraordinary antiquity of the monument, linked to the mythical foundation of Florence,” Sartore explains, "is functional to the ideology of the early greatness of the city. A civic imaginary of which is reflected in Giovanni Villani’s Nuova Cronica where the Baptistery is considered an entirely classical building and even built by skilled workers from Rome, the only one to have survived the destruction of the Goths and unassailable by the passage of time." This is the cultural climate that allows the inclusion of the Florence Baptistery in a core of drawings of ancient monuments. In the Capponi Book we see depicted an interior wall which, however, partially corresponds to the truth since next to the door are placed the funeral monument of the antipope John XXIII by Donatello and Michelozzo (placed on a different side) and to the right a tomb of a warrior (the result of invention). Also appearing are the plan of Theodoric’s Mausoleum in Ravenna, which, however, suffers from the draftsman’s lack of knowledge of the monument (in fact, there are some errors of interpretation), and a reconstruction of the Porta Palatina in Turin: the drawing preserves the structure of the facade of the ancient access to the city, with the side towers, the four fornixes and the orders superimposed on the upper levels, but integrates it freely to imagine its complete appearance. Giuliano da Sangallo, in the Barberiniano Codex, had also attempted something similar, but the architect had compendiumed “the ruinistic notation in the left tower by even inserting a tree that, with its roots, compromises its structure by destroying the three upper arches,” Sartore writes, while "not so the person responsible for the Capponi Book, who leaves the tower intact but alludes to a ruined attic floor."

As for the dating of the folios, scholars who have analyzed the Capponi Book lean toward assigning it to the first quarter of the 16th century, probably between the second decade and the beginning of the third. Some elements appear decisive: the presence, in the sheet with thetriumphal arch, of the Pan mentioned above. mentioned, which was used in 1513 for the preparations of a scenography for Pope Leo X, and then, in the other invention arch, the presence of a term in the likeness of a Silenus that recurs in one of Sangallo’s projects for the completion of the façade of San Lorenzo in Florence, datable between 1515 and 1516, and again the fact that by January 1519 Antonio da Sangallo the Younger and Baldassarre Peruzziconducted a survey campaign at the Forum of Nerva that the author of the Libro Capponi sheets seems not to have taken into account when drawing floor plans of the complex.

We do not know what became of the Capponi Book after its completion. We do know for certain that it was seen, studied and taken as a reference model by the architect Giovanni Antonio Dosio (San Gimignano, 1533 - Caserta, 1611), since for some of his drawings contained in the Destailleur Codex A a full derivation from the schematics of the Libro Capponi has been found. But the sheets probably also ended up on the worktable of another architect, Sallustio Peruzzi (Rome, 1511-1512 - Austria, 1572), based on further findings. The subject of the circulation of the Capponi Book has barely been touched upon, however, and it is likely that new information will be acquired in the future: the study of this corpus of drawings has just begun. Likewise, further knowledge will come from more in-depth studies of the decorative inserts found in the elevations, since some appear to be of very high quality: this aspect of the Capponi Book has, for the moment, been deliberately left out. Thus, several open questions remain that will open new research fronts in the times to come. And this is surely one of the most interesting aspects that an authentic and important discovery always entails.

The origins of the National Central Library of Florence can be traced to the private library of the man of letters and bibliophile Antonio Magliabechi, who in 1714 left his collection consisting of some 30,000 volumes by bequest in his will “for the universal benefit of the city of Florence.” In 1737 the city took possession of the Library and turned it over to the librarian: the act sanctioned the birth of the “Public Library of Florence,” where by decree a copy of all the works that were to be printed in Florence and, from 1743, throughout the Grand Duchy of Tuscany was to be deposited. In 1747 the Public Library (which was also commonly called the “Magliabechiana”) was opened to the public. The institution was further enriched with numerous collections and was then in 1861, after the Unification of Italy, united with the Palatine Library (i.e., the library of the Lorraine family). It was then that it assumed the name Bibliografia Nazionale, while in 1885 it also obtained the appellation Centrale. Since 1870 the National Central Library of Florence has received, by right of printing, a copy of everything published in Italy. Originally housed in the Uffizi complex, since 1935 it has been in its present location, the palace specially built since 1911 to a design by architect Cesare Bazzani, a rare example of library building that is part of the monumental area of the Santa Croce complex.

The National Central Library has a remarkable collection: nearly seven million printed volumes, 24,991 manuscripts, 3,716 incunabula, one million autographs (suffice it to say that as of 2013 the shelving covered a distance of 135 linear kilometers). The manuscript collection is conspicuous: the National Collection includes 3971 manuscripts, including part of the manuscripts of the old magliabechian section, and manuscripts from convent suppressions, and with purchase or gift manuscripts, up to 1905. The Palatine Collection, on the other hand, includes 3102 manuscripts divided into the Autografi Palatini, Baldovinetti, Bandinelli, Vincenzo Capponi, Del Furia, Galilei, Gonnelli, Gräberg, Palatino, Panciatichi, De Sinner, and Targioni-Tozzetti collections. Again, several manuscripts come from suppressed convents, while others are found in the Banco Rari, the Gino Capponi Fund, the Foscoliani Fund, the Ginori Conti Fund, and the Cappugi Fund.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.