An addendum for Bernardino Detti, painter from Pistoia (1498-1572)

I have always looked with interest at the large panel in the Museo Civico in Pistoia that bears witness to the activity of a singular and fascinating artist who was Bernardino Detti: the Madonna of Humility with Saints Bartholomew, Jacopo and Giovannino (fig.1). The work, initialed BDP, appears in a number of documents that ascertain its commission, destination and date: the Pia Casa di Sapienza commissioned it in 1523 for the Chapel of the Oratory of the Spedale dei Santi Jacopo e Filippo alla Pergola in Pistoia, and at that time the painter was twenty-five years old1.

I intervene in the context of a dense and complex critical problem only to propose a small addition, which moreover requires some marginal clarification. I have followed the positive results obtained by critics, especially by Chiara D’Afflitto and Alessandro Nesi2, whose contributions have reconstructed around Bernardino’s name a scanty catalog: thanks to these studies the key-work of the painter, now known as Pala della Pergola, can be read in its more general meaning, but also in its numerous minor components, although some questions remain open.

It is likely that it represents the figurative record of an event related to a child (illness, healing, loss?), made with the intention of evoking the theme of the fragility of childhood and its protection through recalling customs and rituals of the Pistoian territory: introducing locally well-characterized figures and cults (Our Lady of Humility3, St. Bartholomew protector of children and titular of the Pia Casa di Sapienza, St. Jacopo, patron saint of the city for whom a hospital was named), amulets and other elements loaded with symbolic references; trinkets and swaddles for infants, fruits, herbs, flowers, and objects that qualified Pistoia as an important resting place for pilgrims and wayfarers.

In the past I had tried to decipher some of these intriguing presences (the clump of flowers and fruit, the herbs scattered on the ground)4 but I did not pursue the research, which others have instead conducted to a successful conclusion, restoring to the altarpiece the lines of a highly articulated iconographic program.

With respect to what has already been said, it remains perhaps to emphasize again the marked scenographic character of the artist’s main works, which must be looked at keeping in mind the presence in Pistoia of a strong tradition linked to the spectacle,5 and Bernardino’s unscrupulousness in combining people and things, even imposing unusual paths of vision and reading.

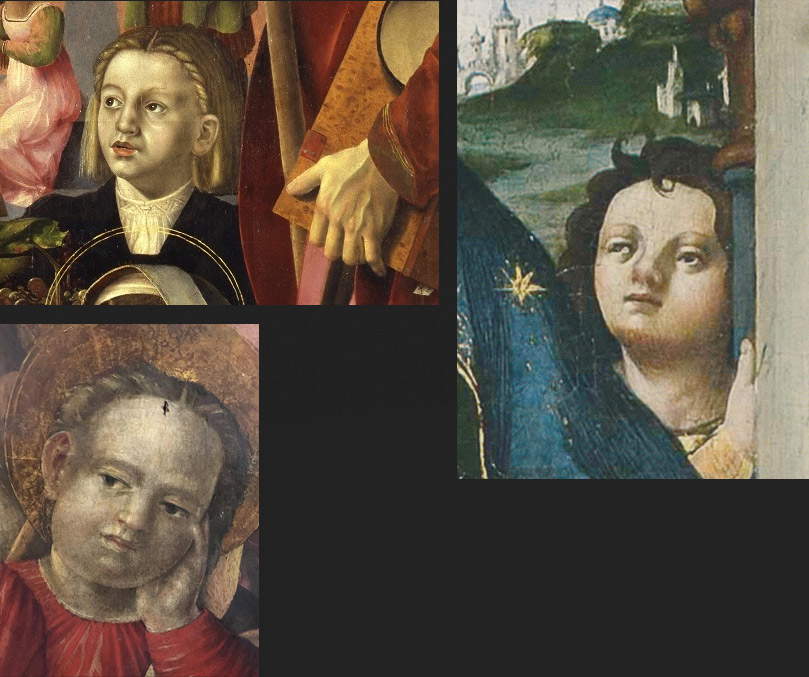

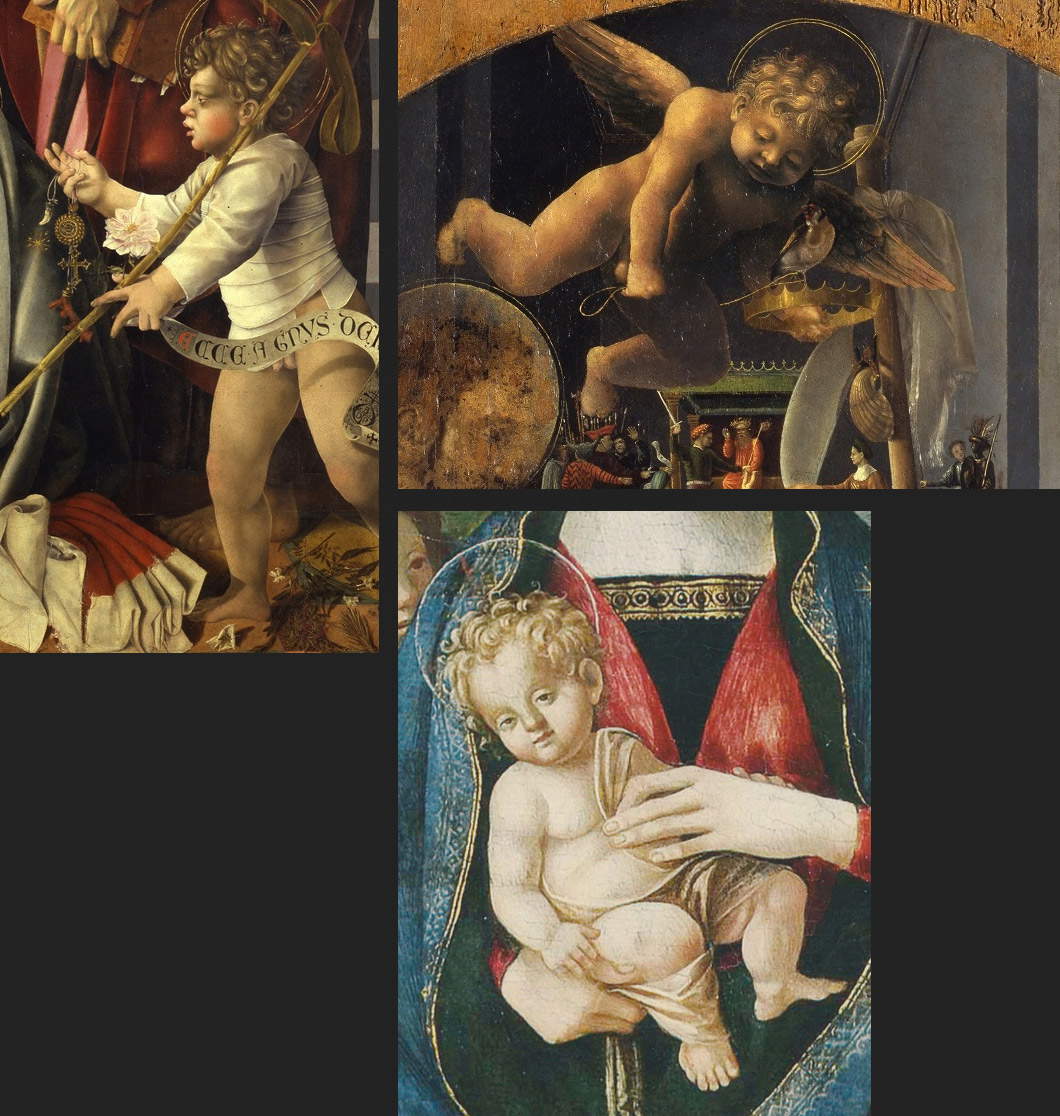

In the Pergola altarpiece, the protagonists, located in a monumental building, are in the foreground and many of them individually converse with the viewer: Saint Bartholomew with the aggressive gesture that flaunts the knife6, Saint Jacopo with his face turned outward7, as well as the Child Jesus, who, with adult physiognomy, points his intense gaze toward the beholder (fig.3); entering the heart of the compositional structure, but without turning toward us, are St. John who bursts in from the right, and an angel who emerges from above (figs. 19, 20): the former offers the Child the signs of his own identity (cross and Agnus dei), a horn, a rose, and a sprig of coral8; the latter a crown for the Mother and a tame goldfinch for the Son. In the crowded central area, the painter then moves from an illusory approach to the viewer (the fly on the Child’s arm9) to a sudden sinking of the view, where a channel opens up showing a spectacle within a spectacle: an elaborate staging of the Judgement of Solomon that through the wisdom of the biblical king would allude to the patron (the Pious House of Wisdom, fig.4); in my opinion, moreover, the space accorded to the confrontation between the two mothers also introduces a reminder of the theme of maternal love. In a further change of direction, the angel towering above the theatrical action traverses the space and projects outward, and the strong foreshortening of the fluttering figure seems to betray a quotation from the more innovative paintings that Rosso Fiorentino proposed around 1520(Madonnas of the Hermitage and Los Angeles)10.

|

|

| 2. Bernardino Detti, Madonna dellumiltà and saints, detail |

|

| 3. Bernardino Detti, Madonna dellumiltà and saints, detail, Madonna and Child |

|

| 4. Bernardino Detti, Madonna dellumiltà and saints, detail, Judgment of Solomon |

Bernardino’s other decisive testimony, the altarpiece at the Royal Castle of Wawel in Kraków, presents itself as a ’living picture’ also linked to the liturgy and worship rooted in Pistoia11 (fig.5). An ideal stepped scaffolding supports the compositional layout, where the vision, advancing in depth, goes from the ground floor to the top, from the solid staticity of the base to the fluid vortex that sees the Madonna in glory with her child on her lap among angels flying unfolding a precious cloth12. It is a grand theatrical machine, where the figures placed at the sides are proposed as explicit supports of a reading path provided with ’entrance’ and ’exit’ (fig.9): on the left St. Jacopo situated from the back and Magdalene showing the jar of ointments, on the right Catherine, who with her blessing hand joins the divine group, while with her arm placed close to her body she invites them to descend toward St. Bartholomew; here, with a real coup de théâtre, the saint’s flayed arm facilitates recognition, while at the same time initiating the observer toward the center, where Saint Zeno, for whom the cathedral was named, sits; moreover, he was also the patron saint of millers, as recalled by the bread that the holy bishop holds in his right hand: a bread akin to that of today, but which also refers back to Eucharistic food. A vivid color palette, also set by the contrast between right and reverse in the fabrics, accentuates the spectacular character of the image.

There are only two Portraits recognized to Bernardino (New York, Metropolitan Museum, London, Wallace collection)13 and in both the strategic arrangement of the objects surrounding the two protagonists reveals the refined taste and culture of a director of rank: musical instruments, parchments, books, inkwell, and even weapons, archaeological fragments, a coin or medal, a pedigree dog, and precious robes qualify the two men as characters of high social standing, ’gentlemen’ and intellectuals.

In the context of the exhibition dedicated to theAge of Savonarola, the Pergola Altarpiece and its author seemed to constitute an isolated episode even if of absolute prominence, while already in the catalog, and then in later times, a network of relationships was coming to light in which Detti received commissions for important works (difficult to match with the concrete reality due to losses and dispersions), but also devoting himself to works of limited commitment (decoration, furniture, restoration) making use of collaborators, and to activities not pertinent to artistic production. The traces of other places and works that may preserve evidence of Detti have been painstakingly collected and commented on by Alessandro Nesi; with respect to the resulting profile, the case that might offer possibilities for further investigation is a painting in a private collection that I am not directly familiar with, and that Nesi himself made known following a report by Andrea De Marchi.14 the title of the work, Sacra Allegoria, itself indicates some uncertainty, which Nesi proposed to resolve by sketching the hypothesis that a variant of the Immaculate Conception theme is proposed in the image. I am sure that Nesi himself will continue to work on the iconography of the painting, which is of very high quality, but which presents multiple questions in relation to the identification and role of the individual characters.

|

| 5. Bernardino Detti, Madonna and Child, Angels and Saints (Wawel Altarpiece) (Krakow, Wawel Castle) |

|

| 6. Bernardino Detti, Madonna and Child, angels and sa ints (Wawel Altarpiece), detail |

|

| 7 e 8. Bernardino Detti, Madonna and Child, angels and sa ints (Wawel Altarpiece), detail of Magdalene and Catherine |

|

| 9. Bernardino Detti, Madonna and Child, angels and saints (Wawel Altarpiece), detail of St. Zeno |

However, I leave the more general topic of the artist’s personality to get to the specific proposal that is the subject of this brief talk.

I had lost sight of the problems pertinent to the novelties and contradictions of Bernardino Detti, when my interest in the personality of the Pistoiese painter was reawakened in the face of a case that surfaced without fanfare in thescope of a fine exhibition and a catalog full of stimulating contributions dedicated to “forgeries”; encompassing in the term not only and explicit counterfeits, but remakes, transpositions and the varied casuistry of re-employments: Primitifs Italiens, le vrai, le faux, la fortune critique15, Ajaccio 2012).

Only on a second or third reading of the thick Catalog did I stop my attention on a composite polyptych, namely a singular pastiche preserved today in Lyon, Chapel of the Jesuit Fathers’ St. Mark’s Center, in which fourteenth- and fifteenth-century elements have been brought together (fig.10): not only paintings, since even the silver frame seems to derive from a skillful assemblage of original fragments and pieces of more recent date. It is a structure of a certain grandeur (219 x 140 cm) in which late medieval and modern fragments are associated, and which is overall elegant despite the impression of strong heterogeneity.

Set into the wooden woodwork are six paintings datable between the late 14th and early 16th centuries. In the center at the bottom is a Crucifixion, referred to Simone de’ Crocifissi; at the sides are two fragments with groups of devotees at the bottom, and at the top are two saints (St. Brigid and St. Catherine), possibly from the Umbrian School. I have no reason to comment on the five small paintings, while I feel I can add some observations in relation to the central panel.

It is a Madonna and Child between two angels, partially altered by repainting16 and a reduction of the panel on the sides (fig. 12): surely the image included at least two other angels of which only a faint trace remains. The work, unpublished until the time of the 2012 exhibition, was considered by some scholars, but these were opinions expressed verbally, with oscillations between painting from Romagna and painting from the Lucca area; in the Ajaccio Exhibition Catalogue the second option prevailed, and it was accepted as the author of the painting the name of Michele Angelo di Pietro da Lucca, from a family originally from Pistoia, while accounting for the variants present in the historical-critical debate and the difference of opinion between two scholars, both authoritative and specifically competent: Everett Fahy who confirmed the reference to Michele Angelo, and Maria Teresa Filieri who expressed doubts, practically rejecting the attribution17.

|

| 10. Polyptych, composition of elements of different ages (Lyon, Chapel of the Jesuit College - St. Mark’s Center) |

|

| 11. Pergola altarpiece, detail. Lyons Polyptych, detail of the Madonna and Child and angels 12. |

|

| 13. Pala della Pergola, detail. 14. Lyon Polyptych, detail. 15. Bernardino Detti, Sacra Allegoria, detail (Florence, private collection). |

I have devoted more than one essay to Lucchese painting of the second half of the 15th century, and especially to the personality of Michele Angelo18, so I intervene on this topic to confirm the position of my friend Teresa Filieri, discarding the attribution of the Lyon painting to the Lucchese painter. Nonetheless, the alternatives expressed by critics (Romagnola painting, Lucca painting) have some justification: in Michele Angelo’s style, although of Florentine background, there emerges in fact a subtle vein of other sign and also a tendency to discontinuity that sees moments of excellence (e.g., some head-portraits) emerge within compositional structures of traditional layout. A slender thread that, in the face of the questions posed by the Lyon panel, led me to move in the direction of Pistoia, toward an environment where the location in a context close to the communication routes that furrowed the Apennine passes favored multiple opportunities for exchange between different schools19. Ultimately that ’otherness’ that characterizes certain aspects of Michele Angelo’s work recalled in my mind that eccentricity that marks the accounts of an elusive and difficult artist like Detti.

Bernardino’s training is undoubtedly linked to the figurative culture of early sixteenth-century Florence, with reference chiefly to Fra Bartolomeo, Piero di Cosimo, Andrea del Sarto, and the other protagonists of the workshop of the manner20: in the certain testimonies of his activity one also catches nuances proper to a transitional style, deviations from the late fifteenth-century tradition, and openings toward the points of extravagance manifested by the promoters of theworkshop. Emblematic is the seated St. John in the center of Pala di Wawel (fig.6): the twisting figure raising an arm is one of the many interpretations of the famous module of the contrapposto, here linked to a formula of Fra Bartolomeo replicated in various forms and in various places, among others in Pistoia by Scalabrino (Cutigliano altarpiece), and also present in the orbit of a painter of ’marginal’ imprint like Zacchia da Vezzano.

I would add that D’Afflitto has rightly insisted on the revelatory imprint of some of Detti’s solutions, evoking Dürer and the graphics from beyond the Alps21; I would add further that in the same perspective are the intrusive draperies (mantles, draperies) where the draperies are intentionally modeled with an ’abstract’ effect: I refer to the cloaks of St. Jacopo (Wawel altarpiece) and of the Madonna sitting on the ground (Pergola altarpiece), the latter crumpled like a fragment of sheet metal (fig.11); in the same altarpiece, I also point out the sumptuous cloak of St. Bartholomew, which must have echoed the texture of equally splendid liturgical vestments. These are all components that confirm the artist’s predisposition for digression and artifice, and his detachment from currents of conventional style.

Scholars who have analyzed the Pistoiese’s work and the relevant documentation have repeatedly pointed out the doubts and contradictions that surface from a profile that can nevertheless be said to be reliable today. Beyond the extensive losses that have compromised an articulate reconstruction of his industriousness, the archival data reveal a character who accepted assignments of varying scope, and who perhaps felt a certain impatience with work to be performed in person: for Bernardino, the son of an influential man and belonging to a family of high social class, manual labor was not supposed to be a strict necessity. Of this we find a small confirmation in the Lyons panel, which also must be evaluated with caution since it has come down to us through events that have compromised its integrity. Nonetheless, an attribution to Bernardino and an early dating, just beyond 1520, might be plausible.

The basic layout of the painting envisioned a placement of the small group of figures within a loggia: of this remain two pairs of columns22 topped by capitals, which, with an architrave, are also worth framing the landscape behind; an undulating countryside, furrowed on the right by a river, where the view sinks toward some buildings, a conglomeration consisting of a bridge and a few towers with pointed roofs in which we recognize a widespread typology marked by Nordic accents. In the loggia, the Virgin stands erect in the foreground, supporting and exposing the Child; the putto is naked, her body veiled by a sash that facilitates the mother’s supportive action, and in the regular face the eyes show a gaze lost in the void. Both are enclosed in the capsule of the blue cloak: a broad, sonorous shell with wavy edges that slips from head to shoulders to hips, and which constitutes the most prominent component of the figural part (one catches a counterpart of this in the Pergola altarpiece, in the cloak of metallic consistency that envelops the Madonna crouched on the ground). The resulting effect is that of a time ’suspended’ around the dominant figure of the Virgin: from the modest neckline of her robe emerge her neck and a polished face, as devoid of disturbance as of affection, which shuns the eye of the onlooker, and evokes impassive pierfrancesque typologies; a face very close to those of the female presences in Detti’s altarpieces, whose full cheeks and hairstyle it shares: straight hair parted by a central parting and gathered behind the nape of the neck (figs. 16, 17, 18).

On either side of the protagonists, the two angels show faces with peculiar features (fig.14): the distant eyes peeking out from half-lidded eyelids, the camused nose, the small, tight, unsmiling mouth are far from the more popularized and appealing angelic types elaborated during the fifteenth century, and, to our eyes, almost verge on pathology. They are faces that have some affinities with that of the little girl who appears in the center of the Pergola altarpiece, in the act of bringing flowers and fruit to the Madonna, and also among those who intervene in the Sacra Allegoria that I fleetingly mentioned earlier (figs.13, 15): among the characters there are some that are decidedly disturbing (stocky build, faces with heavy, expressionless features).

|

| 16, 17. Wawel altarpiece, detail. 18. Lyon Polyptych, detail. |

|

| 19, 20. Pergola Altarpiece, detail. 21. Lyon Polyptych, detail. |

The Lyon panel-assuming that my attribution is correct-does not add any decisive elements to Bernardino Detti’s work, that is, it does not belong to the phase of high stylistic depth that is established in the large altarpieces and portraits; but the two angels, so far from the widely successful formulas, add an additional touch to the painter’s unscrupulousness; skilled in constructing the image but also in disseminating ’pills’ of erudition, allusions to the oral tradition of fairy tales and proverbs, and to the events of the present time, when epidemics and other scourges were bearing down on the population, and especially on those who could not count on forms of protection. In this light, we better understand the images intended for devotion and hinged on the appeal for salvation addressed to the divinity and the saints, which Bernardino interpreted by introducing unprecedented variations, linked perhaps to events whose memory has been lost. A patronage that we can assume educated, but conservative in taste, would not have accepted those characters if they did not have some connection with a part of everyday life. Unfortunately, we do not know how varied was the humanity to which artists in the sixteenth century looked in composing their stories; perhaps the angels with astonished and ungainly faces escorting the Madonna of Lyons had a match in the real presence of physiognomies marked by traits of abnormality: they differ from the images whose physical irregularities had been smoothed out in the previous century, but their rustic peasantry also stands out from the sophisticated imprint of Rosso Fiorentino’s stunted saints, those “devil saints” who, according to Vasari, frightened a patron.

Critical-historical research has encountered many difficulties in identifying the components of the Pergola altarpiece that the passage of time had turned into enigmas, and today almost everything is clarified and motivated; but perhaps Bernardino Detti’s work still presents some obscure passages, and what has been summarized here might serve as an invitation for further investigation.

In the course of writing this text I had the collaboration of a number of friends, to whom I extend warm thanks: Elena Testaferrata, Patrizia Lasagni, Enrico Frascione, and Andrea Baldinotti.

Notes

1 The most extensive entry in relation to the theme addressed here is the Catalogue of the exhibition L’Età di Savonarola. Fra Paolino e la pittura a Pistoia nel primo ’500 (Pistoia 1996), edited by C. D’Afflitto, F. Falletti, A. Muzzi, Venice 1996. All the essays are significant, but I point out C. D’Afflitto, schede pertinenti al Detti, pp.222-226; by the same scholar, see La Madonna della pergola... “Paragone,” 45, 1994, nos. 529-533, pp.47-59. More recent contributions conducted with great commitment by A. Nesi, Bernardino Detti, un eccentrico pistoiese del Cinquecento, “Nuovi Studi,” 15, 2010, pp.88-100; Bernardino Detti, La Pala di Cracovia, Florence 2016,and Bernardino Detti. La Pala della Pergola, Florence 2017. In the essays cited above, it is pointed out that Andrea De Marchi is credited with approaching the Wawel Altarpiece to Detti.

2 An extensive summary of the bibliography from before 1996 is in L’Età di Savonarola 1996, cit., pp.251-261; for later years I refer to Alessandro Nesi’s publications. It is worth mentioning that the exceptional character of some of the works cited below with reference to Detti had been intuited by two Masters who are always in my thoughts: F. Zeri, Eccentrici fiorentini....II, "Bollettino d’arte," XLVII, IV, 1962, pp.216-218; Idem, Italian paintings. A Catalogue of the Collection of the Metropolitan Museum, New York 1971, p.308; C.L. Ragghianti, French Pertinences in the Sixteenth Century, “Critica d’arte” XIX, 121, 1972, pp.3-92 (12-14).

3 On the book held in Saint Jacopo’s hands appears a reference to a passage from a Letter of Saint James containing an exhortation to humility (Nesi, Bernardino Detti 1910, cit., p.89)

4 In relation to the bundle of flowers and fruits I observe that the attempt to fit each component into the individual meshes of a network of symbols is not convincing: these are fruits, flowers, and foliage that ripen and blossom between late summer and early autumn, and it would be reasonable to recognize them as a metaphor for an end-of-life, or as a chronological clue related to the event recalled by the painting.

5 A. Chiappelli, Storia del teatro a Pistoia dalle origini alla fine del XVII secolo, “Bullettino Storico Pistoiese,” XII,1910, 4, pp...Documents preserve explicit traces of performances held in the Cathedral during the Middle Ages, of thecritical attitude of the ecclesiastical authority in relation to the expansion of disguises and dances, the defense by the people and in any case the continuation of the performances between the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries outside the sacred building.

6 It is a constantly present attribute of his, but it was also the emblem of the Pious House of Wisdom. The deterioration of the pictorial surface in the area of the face is due to contact related to devotion, i.e., children’s kisses.

7 I wonder if this might not be the painter’s self-portrait (fig.2). In 1523 he was about twenty-five years old, while the physiognomy of the saint as he appears in the panel might appear to be that of a mature man: however, we cannot judge the appearance of the painted effigies according to our present way of life: in the panel, the figure depicts St. Jacopo as a pilgrim, and therefore shows a tanned face, unkempt hair and beard; however, the liveliness of the gaze could betray the author’s desire to present himself in a direct form, confirming the initials inscribed in the cartouche of the Baptist.

8 The announcement of the Passion (Ecce Agnus dei), the cross, the rose, and at the same time the common trinkets to which scaramantic power was attributed. Evidently Bernardino liked to give visual form to what belonged to the high levels of culture but also to popular beliefs.

9 According to D’Afflitto(The Age of Savonarola 1996, p. 224) the fly, along with withered herbs and flowers, would recall the theme of vanitas.

10 In introducing bold foreshortening forms for the angels in flight Fra Bartolomeo stands out among the Florentine comprimari, but in this case the abbreviated view that crushes the features of the putto’s face seems to derive precisely from Rosso.

11 Nesi(Bernardino Detti 2010, p.90) speculated that the work was commissioned by the Fabbroni family for an altar located in the church of San Domenico. I cannot consult the text of a Polish scholar, M. Szubiszewska, and must refer to the summary offered by Alessandro Nesi whose reservations I share (Nesi, La Pala di Cracovia 2016, cit.).

12 The use of fine textiles inside churches is well attested in Pistoia.

13 Zeri, Italian Paintings 1971, cit, p. 308; Ragghianti... French Pertinences 1972, cit, pp.12-14.

14 Nesi, Bernardino Detti, un eccentrico 2010, cit., pp.94-95.

15 Primitifs italiens, le vrai, le faux, la fortune critique (Ajaccio 2012), edited by E. Moench, Milan-Ajaccio 2012, pp.222-231, entries by E. Mognetti and N. Hatot).

16 Partly removed during the recent careful restoration, on which see N. Hatot, Primitifs italiens 2012, cit. pp.226-231. It is possible that the panel was also reduced in the lower part.

17 Primitifs italiens 2012, cit., file by E. Mognetti, pp.222-226. The hypothesis that the original composition was dedicated to the transfer to Loreto of the house of Our Lady does not seem to be able to be deduced with certainty from its present state.

18 Eclectics of Lucca: news for Michele Angelo di Pietro, “Critica d’arte,” LXIII, 8, 2000, pp.27-42; I pittori nella Lucca di Matteo Civitali. From Michele Ciampanti to Michele Angelo di Pietro, in Matteo Civitali e il suo tempo, Catalogue of the exhibition (Lucca 2004), edited by M.T. Filieri, Milan 2004, pp.95-141; A tutela di Michele Angelo di Pietro, pittore stravagante, “LUK”,23, 2017, pp.126-137.

19 Michele Angelo’s father was a lumber master originally from Pistoia, and his son is also mentioned in the documents as both Michele Angelo de Luca and de Pistorio.

20 I refer, of course, to what was a defining stage in studies of the early 500s in Florence: L’Officina della maniera, Exhibition Catalogue (Florence 1996-97) edited by A. Cecchi and A. Natali, Florence 1961.

21 The Age of Savonarola 196 cit. p.224.

22 Especially the columns in the foreground are barely legible because they have been removed by the strong cropping.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.