Wind, cicadas, calm. The ruins of the monastery of San Bruzio stand on the rounded hump of a soft knoll, hidden among the fields, along the provincial road that leads from the castle of Marsiliana to the village of Magliano, still tightly packed in the imperious circle of its stone and travertine walls. The road crawls through the deserted, golden countryside of the Tuscan Maremma, scorched by the heat of an endless summer. Now and then a grove of holm oaks, patches of shade like mirages sheltered from the fiery darts of a tenacious, unyielding, overbearing sun. On the right, coming from the junction with the regional road, parades the metal mesh protecting the Etruscan necropolis. A row of oleanders signals the presence of a lonely farmhouse. Halfway up towers a small circle of very tall cypresses, which seem put there to guard the cultivated farms. And then, in the silence, after a bend, there in the distance is San Bruzio to reinvigorate the view.

The demands of modern tourism have evidently forced local administrators to open a parking lot, unmarked: one finds it suddenly, neat expanse of dust and gravel lying along the edge of the provincial road. No parked vehicles. On the opposite side, a dirt path guides the traveler to what remains of the ancient 11th-century monastery. Today San Bruzio is a detour from the routes of those who traverse the length and breadth of the Maremma lands. Distant, the straight stretch of the Aurelia drags hordes of indomitable vacationers, mixing the means of those who reach the villas and luxury hotels of the Argentario, and those who trudge toward the campsites that lie between Fonteblanda and Albinia, villages where everything is still simple, where everything is still sincere, where life flows slowly between a fish festival and an ice cream in the square, where the heirs of those who were once called “villeggianti” still arrive, they descended from the regions of northern Italy, and every summer, come what may, they slept for weeks in the same houses, fed themselves in the same places, sunbathed on the same beach.

It is on the shoreline today that life is. In ancient times, however, one carefully avoided drawing routes that passed along the coast: the Maremma was a huge swamp, boundless, deadly, infested with brigands. There was therefore a serious risk of not returning alive from one’s journey, and one passed by the more salubrious and civilized hinterland. From these parts, then, perhaps not even many pilgrims passed through, who, to head for Rome, preferred to travel the itineraries of the Sienese, welcomed by the monks of Sant’Antimo, by those of San Michele in Poggibonsi, of San Galgano, of Abbadia a Isola, of the many monasteries that dotted the Val d’Orcia, the Crete, the Val d’Elsa, and the hills around Amiata. In the wild Maremma, farthest from the pilgrimage routes, the abbeys were mainly places of production, farms ahead of the letter, fortified granges run by friars and monks, along the road that descended from the Amiata to the port of Talamone, in the lands that were once the Aldobrandeschi. And they offered shelter not so much to those on their way to the Eternal City but, perhaps less romantically, to workers in the salt pans at the mouth of the Albegna and to those in the iron mines who moved between the mountains and the sea. Perhaps it might have happened, every now and then, that some scattered wayfarer would venture through this countryside, even going so far as to lap the Riviera: among the ruins of the abbey of San Rabano in Alberese, not far from San Bruzio, a pilgrimage sign bearing the image of St. Nicholas was found. A sign that someone had to pass through these little-visited plains as well. It is not known, however, whether San Bruzio also served as a shelter for pilgrims.

We know little or nothing about this complex. The fact that it was dedicated to an unusual saint, Saint Tiburtius Martyr, mispronounced as “Bruzio” by local speakers, does not help shed light. We do not know when St. Bruzio was built, although the language of what is left goes along with the idea that the first stone must have been laid long before the thirteenth century. We do not know what it must have looked like when it was intact. We don’t know when it was abandoned. We don’t know why it was destroyed. We are not even certain that there was a monastic community here, although there is a very good chance that Benedictines built the structure: the hypothesis is supported by the stylistic evidence that can be found among the ruins. A Maremma scholar from the early twentieth century, a certain Carlo Alberto Nicolosi, author of several books on these lands, amused himself by imagining that the church of San Bruzio had been left unfinished: solid surviving ruins, absent traces of plaster or embellishments, and enough for the scholar to imagine a factory that at some point in history remained interrupted, for who knows what reasons. This was not the case: there are ancient documents that nonetheless attest to a presence in San Bruzio. In 1216, the “church of S. Tiburzio di Malliano” is mentioned as a dependency of the abbey of Sant’Antimo. In 1276 and then again in 1321 it is mentioned in the tithe lists. In 1356 it appears in the Statutes of the Municipality of Magliano, where a tax is imposed on the citizens to repair the roof of the church. Then the sources are silent.

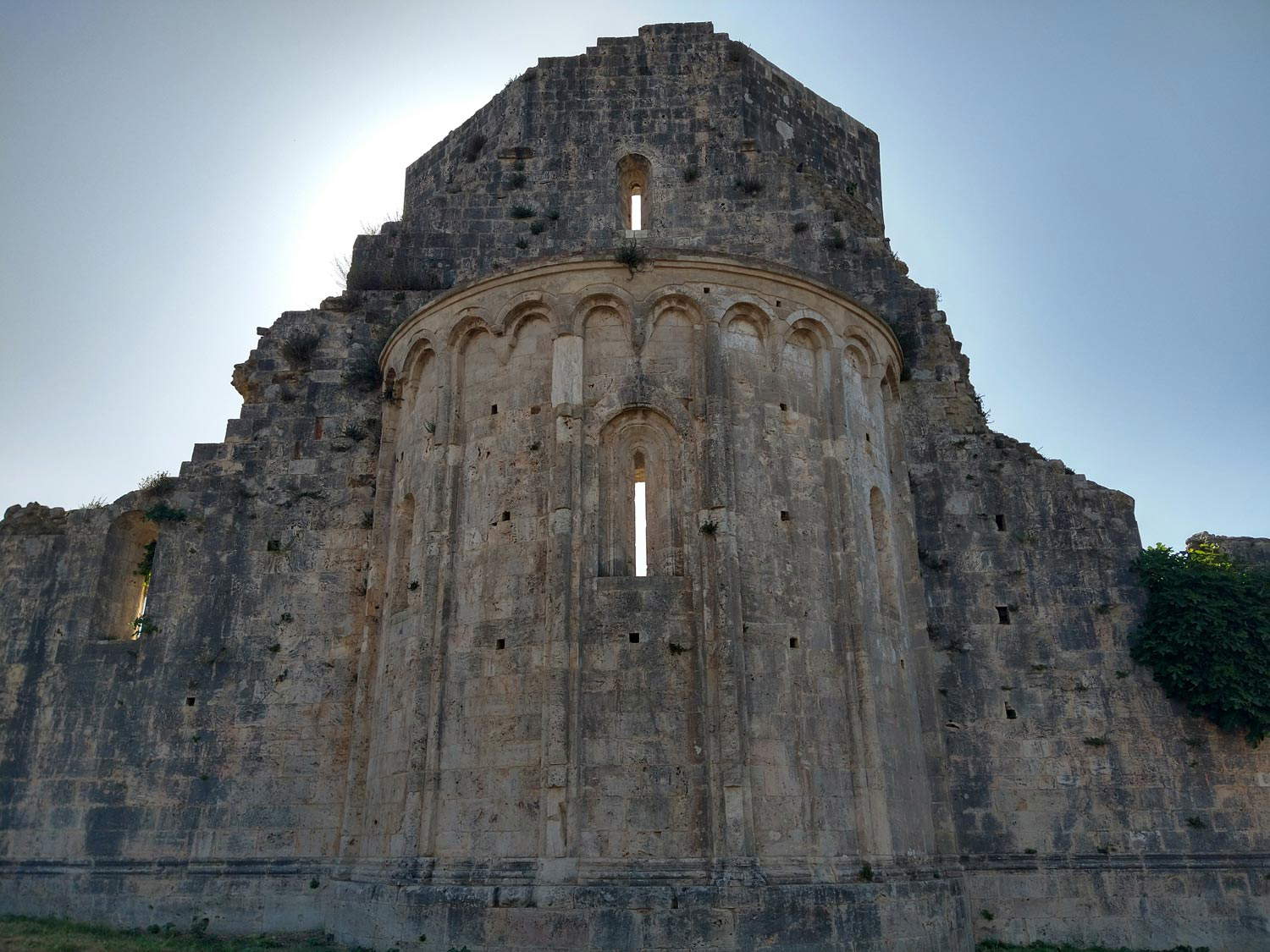

The capocroce, the part of the church beyond the transept, is all that remains of San Bruzio. With the obvious exception of the stones scattered on the ground all around. At first, when one is still on the path, it seems as if the ruins of the ancient monastic church are drowning among the olive trees. Then, when one arrives in front of the ruins, one feels as if shocked, overwhelmed, overpowered by their imposing gravity. In the eighteenth century, the inhabitants of the area called San Bruzio the “pagan temple”: they knew no other explanation for those remains, and the sculptures that still adorn its capitals, a figurative language of which they had lost memory. But like us today, they felt a sense of disquiet before the solemn majesty of the ruins of San Bruzio. Perhaps they did not even dare to set foot in it, perhaps they approached with a certain fear of that strange, wounded, stumped, disfigured construction, about which they knew little less than we do.

And who knows if, three centuries ago, San Bruzio already looked as it does now. Climbing the knoll, one is greeted by the geometric form of the triumphal arch, beyond which, looking frontally at the ruined church, there remain shreds of the transept walls, and a section of the tiburium, with single-lancet windows on four sides, resting on as many mighty arches. Having completely lost the hall, all that remains is the chancel, the stumps of the arms of the transept with the limestone supporting structure, and the semicircular apse, decorated on the outside with pairs of hanging arches separated by pilasters creating five regular sections, where three single-lancet windows open. We pass the triumphal arch, stand in the middle of the presbytery and look upward: above the tiburium was once grafted a dome that we imagine tall and majestic, since only the ruins reach a height of about fifteen meters from the ground. Something similar to the dome of the abbey church of Santa Maria Assunta in Colle Val d’Elsa: San Bruzio must have looked not too dissimilar. Now we see instead an octagon open to the sky, with a few weeds depriving the eye of a portion of blue. The arms of the transept were once covered by cross vaults, which we can now only guess at. Between the chancel and the tiburium, the norms of balance that guided the ancient architects can be perceived with sunny clarity: the appearance of the ruins, “which has stood the test of time,” wrote Mario Salmi, “is sharply geometric in the dome over niches, and the capitals still in place present a harmonious mixture of zoomorphic and vegetable elements of intense plasticism.” The great scholar believed that the capitals of San Bruzio were close to those of Sant’Antimo “in sharpness of sign, in relief, in the similarity of the translated motifs and even in the minute concentric folding of the garments.”

The style of the capitals, the fineness of the decorations, the geometric rigor of the travertine ashlars used for the construction, as well as the strict dimensional ratios between the various elements of the building, have led and continue to lead one to think that the architects active at San Bruzio were of Lombard origin, perhaps masters from Comacino, who had the merit of constructing, under the village of Magliano, a building that has no equal. A unicum, scholars Barbara Aterini and Alessandro Nocentini have defined it, the sum of “various architectural experiences and which,” Nocentini explains, “among those of the Abbey of San Rabano or the parish church of Sovana turns out to be the oldest in terms of morphological coherence of the wall face, and expresses a geometric-static correctness possessing a harmonious form and ingeniously simple geometries.” And simple, too, are the figures left on the capitals: flowers, plant motifs, three elements (a bovine protome, a lion, perhaps an angel) that would seem to be the symbols of three evangelists, a bizarre anthropomorphic figure with its body assuming an unnatural posture and its head turned a hundred and eighty degrees. Perhaps the personification of some sin: the subject is rare, but found in Romanesque churches, even far from here. He wants a tradition that in Bologna, looking at similar figures, Dante drew inspiration for the punishments inflicted on the damned in his Comedy. Even the capitals of San Bruzio suggest the presence of Lombard masters, who brought to Tuscany the typical repertoires of the North.

In the midst of so much ruin, the interior wall of the apse has been preserved quite well, with its smooth and regular ashlars of travertine: if before entering there was a sense of reverent uneasiness, now one begins to feel a shadow of tranquility, that impression of limpid contemplative quiet that one can only experience inside a Romanesque church, inside one of those ancient temples so simple, so severe, that Giovanni Lindo Ferretti, keeping in mind the Romanesque parish churches of Lunigiana, considered most responsive to an idea of a pure church, a “harmonic case in brick or stone, perfect for worship and prayer, listening, inner abandonment, prayerful community, the welcoming of the body and the soaring of the soul to the Spirit.” At San Bruzio, this abandonment is amplified by the sounds of nature, by the light salt breeze that creeps through the ruins and gently shakes the olive fronds, by the monotonous and cadenced song of the turtle doves, by the plants that have taken possession of the stones, the only living presences in the church where the Benedictines once officiated, by the uncovered tiburium that invites one to look up and gaze for a moment at the infinite. Divinity, then, lives inside every crevice, imbues every stone, every human handiwork, is in the breeze, in the olive trees, in the turtle doves, in the sky, pulses in every single blade of grass that surrounds the church of San Bruzio and, inside, serves as its floor.

The beginning of the history of San Bruzio is lost in the mists of the Middle Ages, its end swallowed up by time. No trace to testify to the reasons for the ruin of the complex, whether by a natural event or by devastation wrought by human beings. Perhaps simply abandoned because the economic situation changed, corresponding with the passage of the fiefs of the Aldobrandeschi under the rule of the Republic of Siena. Perhaps the ruin of San Bruzio is linked to the vicissitudes of the port of Talamone, passed to Siena at the beginning of the fourteenth century, and held by the new rulers with enormous difficulty, because of the aversion of the turbulent Pisan neighbors, who lost no opportunity to attack the Maremma port of call several times, hostile to the maritime policies of the Sienese. Fact is, since the 15th century, any documentary clue about the monastery has been lost. San Bruzio continued perhaps for some time to offer occasional shelter to those who passed this way, as the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century pottery fragments found in the archaeological excavations that affected the structure would suggest. Then, centuries of darkness and silence. Dead were the Aldobrandeschi, ruins their castles. Died the Benedictine monks, collapsed their monasteries, died the cartmen who in Talamone loaded iron from Elba Island and brought it to the processing centers of inland Maremma. With the imagination, perhaps, one can still imagine San Bruzio as the living place it was between the Two and Fourteenth Centuries. Imagine the monks at prayer, studying, working, hearing the sound of their footsteps on the stones. Imagine the voices of the cartwrights and salt workers arriving here blaspheming God, Our Lady and all the saints for their meager lives. Imagine what this place must have once been. In ancient times teeming with life, embedded in a system of production centers, warehouses, fortresses, and road axes. Today shrouded in the silence of the Maremma countryside.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.