A fixture of summers in Livorno for nearly four decades (the first edition was in 1986), Effetto Venezia is a charming event that enlivens the streets, squares and canals of the city’s most atmospheric neighborhood, Venezia Nuova. Having escaped the gutting of the Fascist era, and affected less than other areas by the bombings of 1943-1944, the district maintains a colorful and seductive atmosphere, evoking the era of the great merchant fortunes of the port of Livorno. Built from 1629 as the first expansion of the Medici city, designed by the Sienese architect Giovanni Battista Santi, the district rose on a marshy area with techniques (and labor) imported from the Serenissima, going by the characteristic name of Venezia Nuova, partly because of the dense network of navigable canals, still clearly legible today.

The festival, organized by Fondazione LEM (Livorno Euro Mediterranea) and the Municipality of Livorno, usually takes place in the first week of August and attracts a large and diverse audience with an intense program that includes lectures, meetings, music readings, performances by street artists, dance, theater workshops and more. Of great appeal are the concerts, with free admission, on the scenic stages set up at the Fortezza Vecchia, in the Piazza del Luogo Pio and at the Fortezza Nuova, as well as on the beautiful 17th-century bridges, in the small squares and in the docks, tangible memory of the district’s ancient mercantile soul. Effetto Venezia, however, is also an opportunity to rediscover some sites of great artistic interest, going to explore often neglected aspects of the city of Livorno, still relegated, in the common perception, to a destination that is not very appealing from a historical and cultural point of view.

The Museum of the City of Livorno (Polo Culturale Bottini dell’Olio - Piazza del Luogo Pio), with its recently rearranged contemporary art section, is offering special openings in the evening hours, until midnight, with three new exhibition projects of varying inspiration. The museum facility is housed in the eighteenth-century Bottini dell’Olio complex, a sprawling oil warehouse (it is said it could accommodate twenty-four thousand barrels) commissioned by Grand Duke Cosimo III (1642-1723) accompanied by a fine ecclesiastical building, formerly named after the Assumption and St. Joseph and now deconsecrated, with a richly decorated stucco interior: it was erected between 1713 and 1715 by Florentine architect Giovanni Maria del Fantasia (1670-1743), a leading figure in the city’s late Baroque urban renewal, who erected his own tomb there.

The evening boat tours (departure at the Scali del Monte Pio) allow you to immerse yourself in the most authentic face of the city, on a route through the festively lit ditches that reveals its nature as a real road system, designed to move goods, among cellars at the water’s edge and ancient scalandroni (the typical paved ramps that gave access to warehouses and emporiums on the mainland).

Standing out above it all are the two monumental churches that find themselves integrated, in their own right, into the Effetto Venezia itineraries: Santa Caterina and San Ferdinando Re, open until late with events and guided tours. The former dominates the urban landscape of New Venice with its tall octagonal dome, and hosts, during the event, concerts of sacred music and meetings on the theme of the spiritual meaning of sound. Erected from 1720 for the Dominican fathers, on marshy land known as the “Cemetery of the Poor,” Santa Caterina experienced a troubled construction history, conditioned by continuous economic problems. The building site dragged on until 1756 with the alternation of various architects, from the aforementioned Giovanni del Fantasia, to whom we owe the initial design of the centrally planned church, to the more famous Ferdinando Fuga (1699-1782), sent to Livorno by the prior of San Marco in Florence to solve the early static problems of the dome. The interior features extensive fresco decoration, much of it nineteenth-century, but as you move forward through the large chapels you will also encounter eighteenth-century frescoes by Livorno-born Giuseppe Maria Terreni (1739-1811), in the chapels dedicated to St. Catherine and Our Lady of the Rosary. On the back wall of the choir, behind the rich high altar created in 1758 by Bartolomeo Casserini (†1773) of Carrara, stands (in an unfortunately very elevated position) the large panel with theCoronation of the Virgin by Giorgio Vasari (1511-1574), painted around 1571 for the chapel of San Michele in the Vatican, a victim of Napoleonic spoliation and purchased in 1799 by Livorno entrepreneur Filippo Filicchi, whose family made a gift of it to the Dominican church (1818). Filicchi, the first U.S. consul in Italy, is also credited with frequenting (commemorated by a plaque) St. Elizabeth Seton (1774-1821), the first American to be canonized by the Catholic Church.

Of great interest, finally, is the church of San Ferdinando Re, a vivid testimony to the deep rootedness, in the Leghorn context, of the particular cult of theTrinitarian Order, an ancient community of religious (founded in 1174), whose missionary vocation was, and still is, aimed at the liberation of slaves. Having arrived in the Grand Duchy of Tuscany in 1653, the French Trinitarians preferred to settle in the lively and cosmopolitan Livorno, rather than in Florence, sensing how the intercultural nature of the port city, with the strong presence of communities Oriental and Jewish, could prove strategic for their redemptive activities, aimed mostly at the ransom of Christian slaves held in North African cities, from Algiers to Tunis and Tripoli.

Construction of the new Trinitarian church, also known as “della Crocetta” (from the order’s coat of arms), began in 1711, designed by the great Florentine sculptor and architect Giovanni Battista Foggini (1652-1725), and was quickly brought to completion (1716) by the usual Giovanni del Fantasia. The sobriety of the exterior, with its unfinished facade, does not give a glimpse of the sumptuous decoration of the interior, embellished with a majestic sequence of eighteenth-century marble sculptures, executed by one of Foggini’s best-known pupils, the Carrarese Giovanni Baratta (1670-1747) and his nephew and continuator Giovanni Antonio Cybei (1706-1784).

The eye is immediately drawn to the sculptural presence of the high altar, the visual and devotional fulcrum of the entire building; erected by Baratta between 1711 and 1717, the altar is striking in its monumentality and sense of movement, accentuated by the outward tilt of the columns and entablature, and the contrast between white and polychrome marble. At the center of the whole is one of the masterpieces of 18th-century sculpture in Tuscany, the group with theAngel freeing two slaves, an admirable summary of the Trinitarians’ missionary aims. Baratta skillfully constructs an image of great elegance and immediate legibility, uniting in an admirable whole three figures in the round, almost suspended in a dimension between the earthly and the divine, in the center of the church. The great angel, supported by an ethereal mound of clouds, breaks the chains of a slave, who seems almost to be ascending toward the overarching motif of the Glory of the Holy Spirit, enhanced by a gilded metal ray. Another slave, with unmistakably Moorish features, waits with folded hands for liberation, but his feet are still constricted by large shackles, perhaps signifying the binding bond to the Islamic creed (which Europeans of the time would have unhesitatingly called “false faith”).

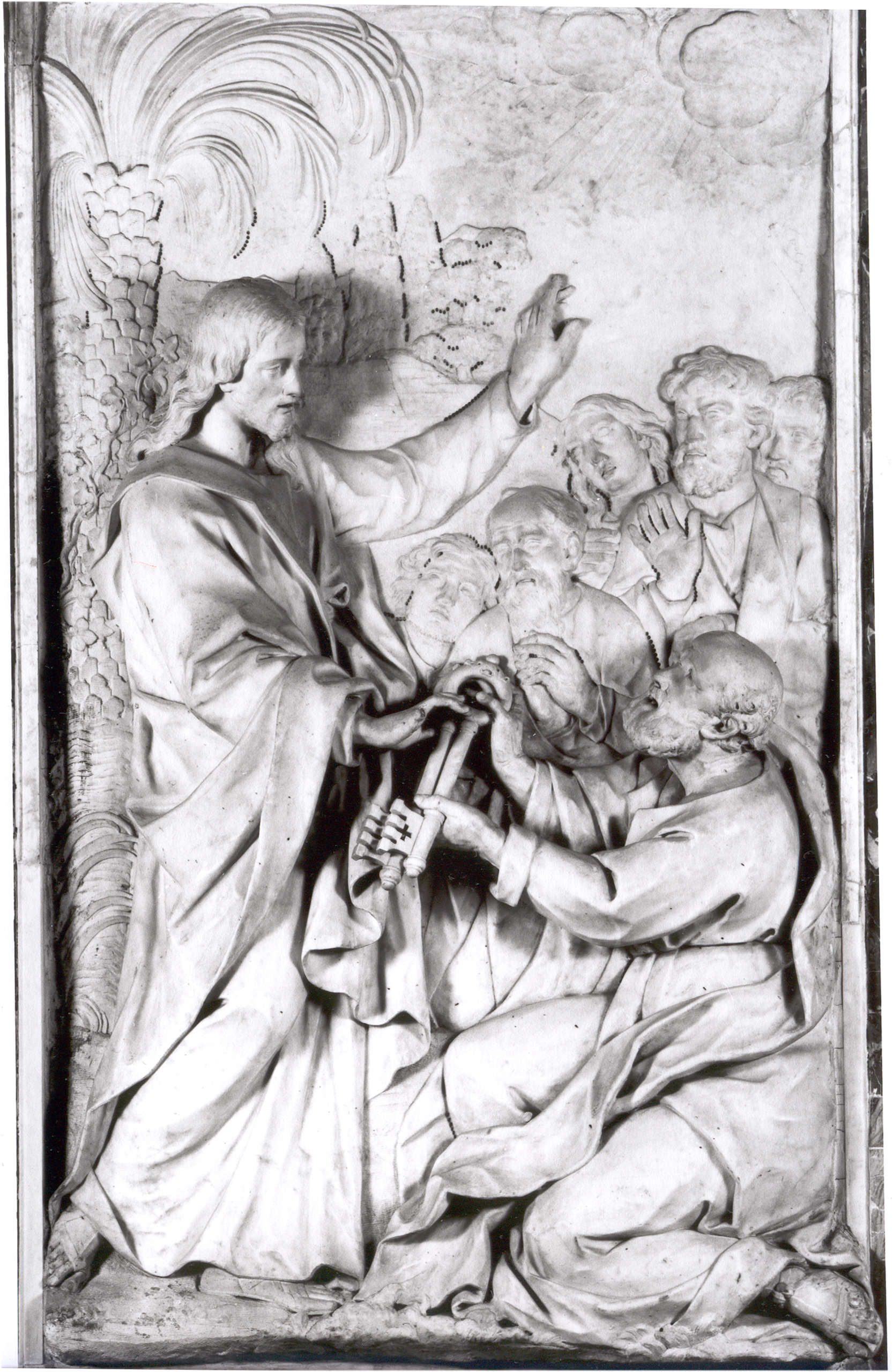

This emotional climax, in which sculpture and architecture appear intimately united and functional to each other, is tempered in Baratta’s highly refined bas-relief ovals with the theological and cardinal virtues(Hope, Faith, Justice, Temperance, Prudence and Fortitude) that surround the altar and ideally accompany toward the nave chapels. The second chapel on the left, dedicated to St. Peter, was made by Baratta between 1721 and 1723, and embellished with an exquisitely crafted marble altarpiece depicting the Handing over of the Keys to St. Peter, while on the side altarpieces are two precious ovals with the famous Domine Quo Vadis? scene and the Crucifixion of St. Peter.

The facing chapel, named after the Founding Saints (1768), was instead decorated after Baratta’s death by his nephew Giovanni Antonio Cybei, the first director of the Academy of Fine Arts in Carrara. In full continuity, stylistic and visual, with what the older master had done, Cybei sculpted for the altar a marble relief depicting the founders of the Trinitarian order, Felix of Valois (1127-1212) and John de Matha (1160-1213) in the act of adoration at the feet of the Holy Trinity. The upper part of the work is directly inspired by the large canvas with the Liberation of the Slaves, executed in 1750 by Corrado Giaquinto (1703-1766) for the Trinità degli Spagnoli in Rome. It is necessary at this point to point out that the Roman church belonged to the Spanish Trinitarians, while Cybei himself, who studied painting in Giaquinto’s studio precisely in 1750-1751, had been in relationship with the Leghorn Trinitarians for some years. In his peculiar qualification as sculptor and priest, in fact, Cybei had a special affection for the religious of the Crocetta, to whom he had promised to make an altar at his own expense as early as 1750, and it is to him that we owe the arrival of this particular cult also in the city of Carrara, where there still exists an Altar of Redemption (1768, in the cathedral of Sant’Andrea), at the foot of which he wished to be buried.

Finally, the nave is enriched by four full-length statues of the highest quality, representing as many sanctified sovereigns, representing four European nations: St. Ferdinand of Castile (for Spain) and St. Edward (known as The Confessor, for England), were executed by Baratta, while St. Louis (for France) and St. Henry the Emperor (for the Empire), by Cybei.

The ensemble, completed by a luminous stucco decoration and recently restored, is of great charm; there are few, and of great prestige, ecclesiastical decorations comparable to that of St. Ferdinand (in terms of grandeur of marble decoration and statuary) in eighteenth-century Tuscany, and Livorno’s Trinitarian church (still officiated by the order) makes a decisive contribution to restoring Livorno’s cultural centrality.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.