American Gothic: one of the world's most famous American paintings was born from a house

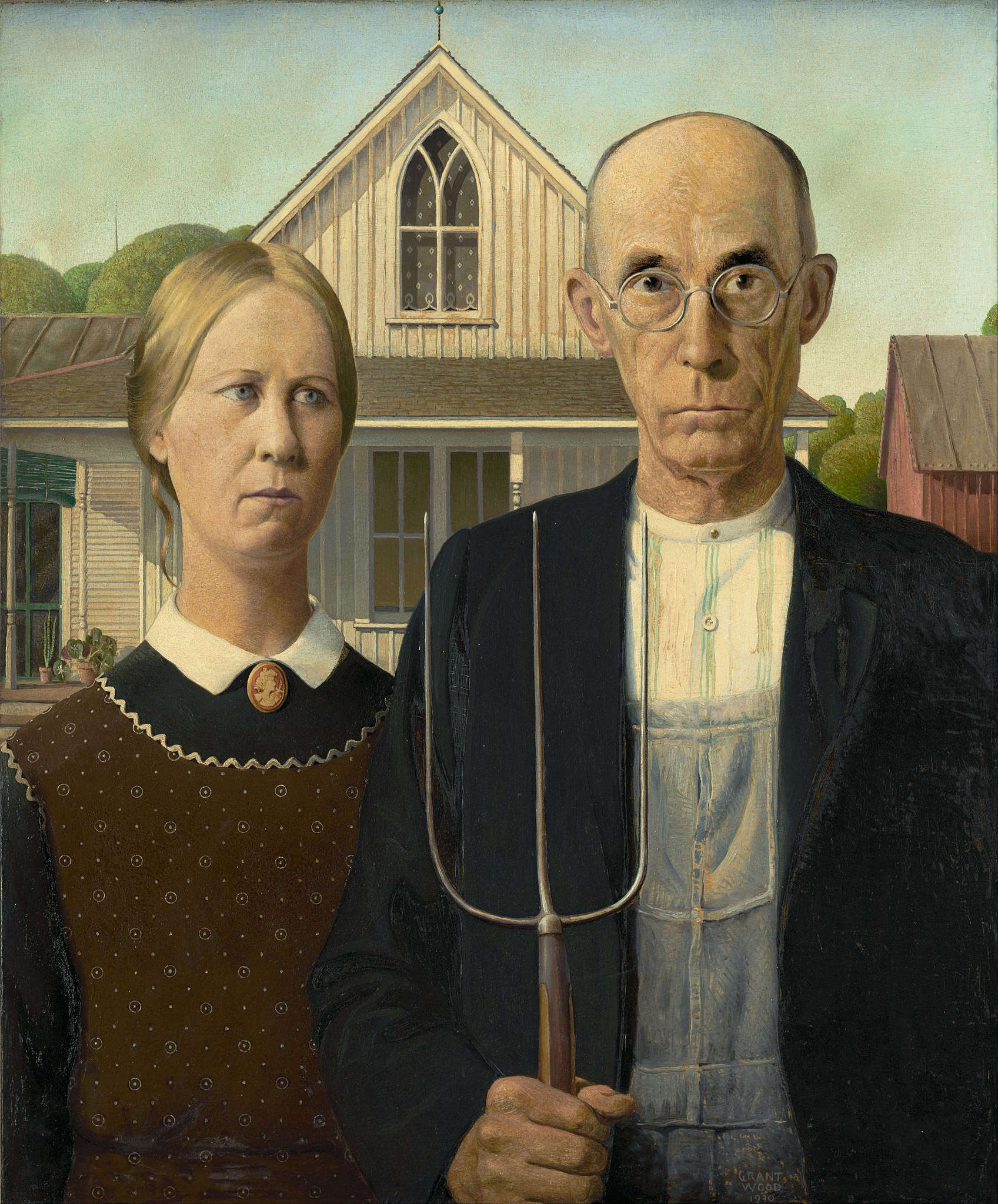

From a chance encounter with a house came one of the most famous American paintings, American Gothic by Grant Wood (Anamosa, Iowa, 1891 - Iowa City, 1942). The artist had been invited in the summer of 1930 by Edward Rowan, director of the Little Gallery in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, to hold an art exhibition in the small town of Eldon, located in the state ofIowa in Wapello County. It was a kind of art outreach experiment to bring art to rural areas of the Midwest: “Mr. Rowan announces,” reported theOttumwa Courier, the Wapello County newspaper, “that the extension work in promoting the fine arts is intended to show that the small Midwestern community, completely isolated from certain contacts, will respond with the utmost warmth when given the opportunity to appreciate the fine arts.” The experiment lasted for a month and included an exhibition by a different artist each week, drawing and watercolor classes for children, and music lessons for older children; it was for one of these weekly exhibitions at theEldon Art Center that Grant Wood was invited by Rowan and had the opportunity to visit the small town.

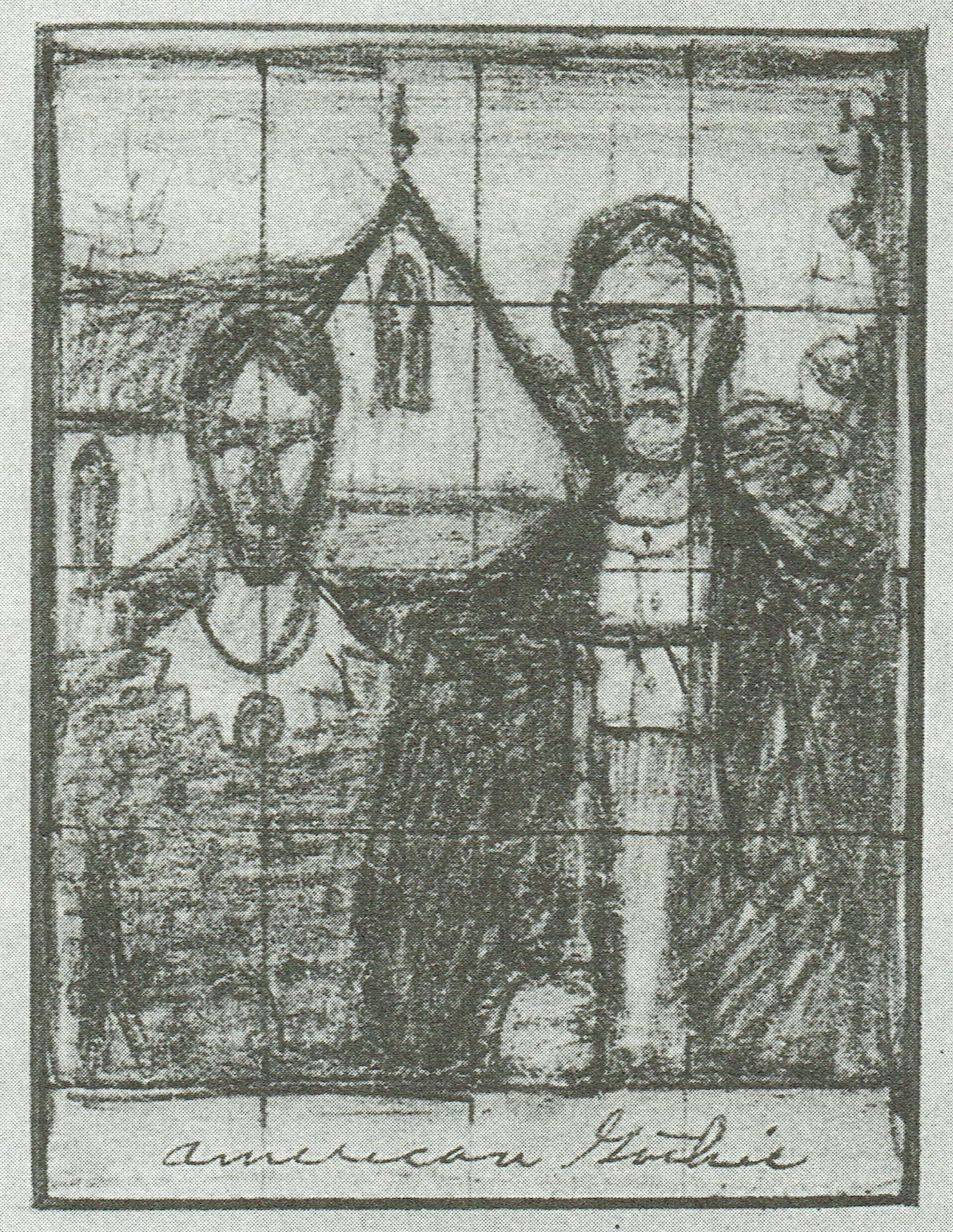

And it was on a tour with one John Sharp, an art student at the University of Iowa who often attended the Little Gallery and thus knew Rowan, that the artist first saw the house that inspired American Gothic. He was especially fascinated by the large Gothic window at the top of the facade, which he nevertheless called almost pretentious for such a small house. According to several investigations made on the house, it seems that that large pointed-arched window was used to get furniture in or out of the upper floor, because the interior staircase was too narrow to accomplish this operation. However, the introduction of Gothic windows in houses was typical of a well-known style that began to spread in the United States in the mid-nineteenth century, the so-called Carpenter Gothic, which had the merit of adding extravagant and elegant Gothic-esque details to small and humble houses to beautify them architecturally. Characteristic elements were, for example, very pitched roofs and gables, wood plank siding, porches with carved railings, and pointed-arched windows. It was a style that allowed houses to be built quickly and cheaply because of the abundance of wood available and the invention of fretwork saws, with which it was possible to replicate the finishes of masonry Gothic cathedrals on the wood of these country cottages. However, by the time Grant Wood saw Eldon’s house it was the summer of 1930, so the Carpenter Gothic style was no longer considered fashionable, but rather somewhat antiquated, since after more than fifty years the architectural style by which houses were built had changed. The artist immediately sketched out a drawing of the house and then once he returned to his studio in Cedar Rapids, where he was working, he finished the painting. He also thought about adding the possible inhabitants of that house to the scene, and who could they have been if not the “American Goths,” as he called them? He asked his sister and his dentist to be his models, and when he finished the painting, he sent it to theArt Institute of Chicago to be displayed in the museum’s annual exhibition of American paintings, and it was admitted.

But who were the real owners of Eldon’s “Gothic” house? Actually, the house had several owners over the years. The first were Mr. and Mrs. Dibble, Catherine and Charles, who had it built between 1881 and 1882 (which is why the house is also known as the Dibble House). It appears, however, that they lost the house due to overdue taxes and so it was sold, later passing from property to property. Until, in 1991, then-owner Carl E. Smith decided to donate it to the State Historical Society of Iowa, a historical society that serves as the official historical repository for the state of Iowa, which from 1991 to 2014 continued to rent the house, asking tenants to also act as janitors in its absence, since the society’s headquarters is located almost two hours away from Dibble House. The current owner, however, is the state of Iowa. It has also been on the National Register of Historic Places since 1974, and next door theAmerican Gothic House Center opened in June 2007, which includes an exhibition gallery, a multimedia room, and a gift store, to also tell the story of the house made famous by Grant Wood’s painting through tours and visits.

Returning to the man and woman depicted posing in front of the house, a choice that probably harked back to the widespread custom among photographic travelers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries of having their subjects pose in front of houses, in part to testify to the deep attachment people had with their homes inrural America, was actually just the artist’s choice: when Wood first saw the American Gothic House there was no person there in front. The scene that seems so realistic in truth is not. Even the models, her sister Nan Wood Graham and her dentist, Dr. Byron Henry McKeeby, were not quite like the figures depicted: the woman had a more elongated face than her sister’s and looked more old-fashioned, while the man was a bit more like her, even though he was older in reality. More importantly, the two never posed together. It is also unclear what the relationship between the man and woman depicted in the painting was: father and daughter? Husband and wife? In a letter, the painter refers to the woman as the man’s “now-grown daughter,” but this remains ambiguous to this day. What is certain is that his intent was precisely to portray two “typical” Midwestern people in front of the antiquated house. As U.S. art curator Sarah Kelly Oehler explains, the artist associated the woman with the domestic elements of the house, while connecting the man to the barn and farm work. In fact, Wood placed a pitchfork (originally a rake, as seen in one of American Gothic’s early pencil sketches) in the depicted man’s hand and added a barn next to the house. The prongs of the pitchfork are then repeated both in the seams of the dungarees worn by the man and in the stripes of the shirt, but also in the lines of the house. Note also the repetition of the motif of the woman’s apron and that of the curtains seen behind the arched window. Through the repetition of forms, the artist wants to create links between the figures and the elements of the house; it is a means of unifying the entire composition. Even the Gothic window, if you look at it closely, is made up of two equal arches that then join in the tip of the great whole arch: the composition of the window is repeated in the whole composition of the painting if you consider the two human figures standing next to each other as the two equal arches and the roof of the house joins them in the same way that the tip of the great arch of the window joins the two smaller arches.

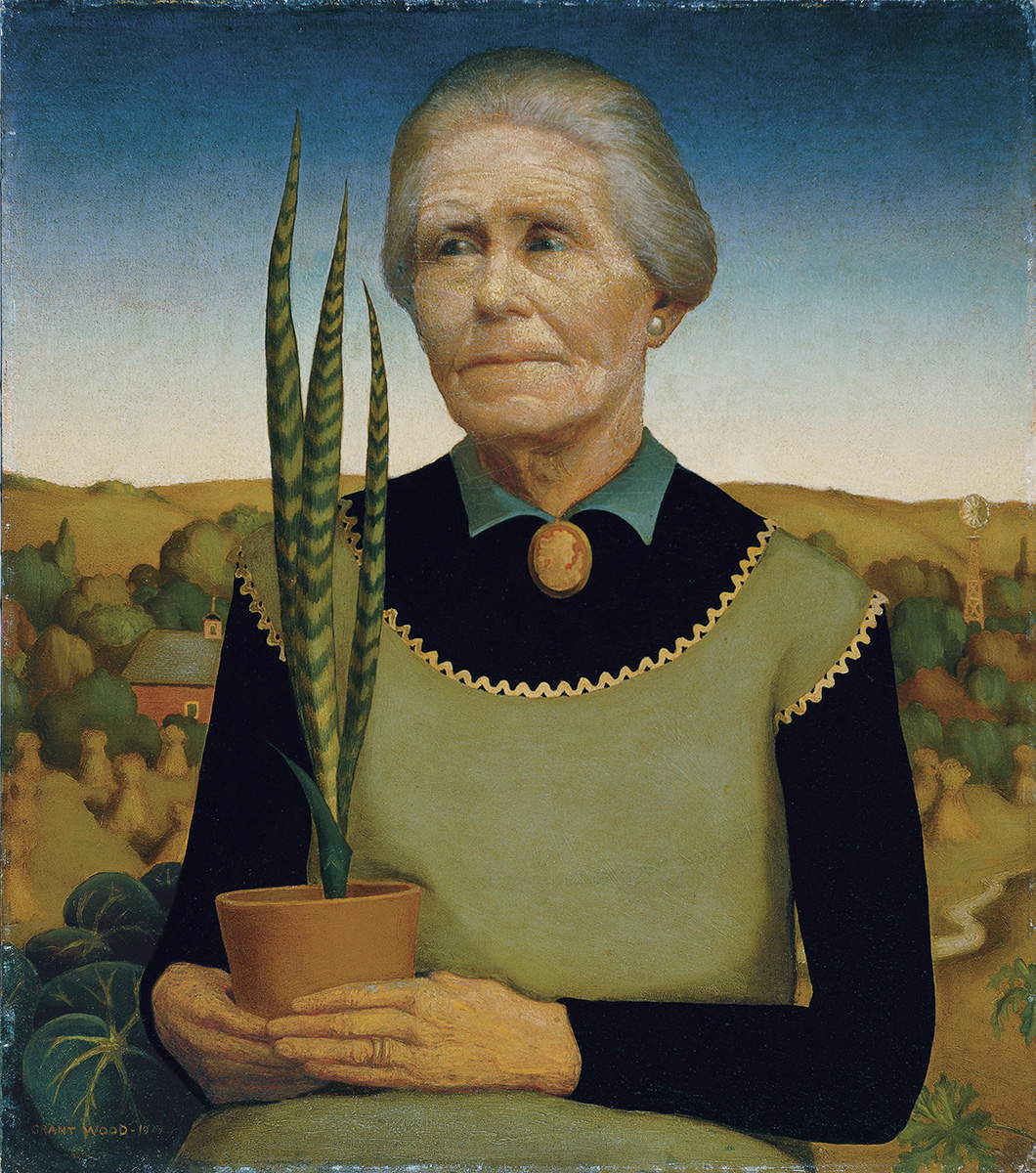

Another item to note are the plants on the porch, namely a “beefsteak” begonia and mother-in-law’s tongue (the latter according to Wanda Corn, author of Grant Wood: The Regionalist Vision, might allude to the ruggedness of women in rural America); in form however, the begonia with the beefsteak leaves echoes the trees sprouting behind the house and barn and to some extent the woman’s hair as well, while the three leaves of the mother-in-law’s tongue echo the prongs of the pitchfork, the seams of the dungarees and the stripes of the shirt. The same plants then appear in another work by Grant Wood, Woman with Plants, in which the painter depicts his mother with the “beefsteak” begonia by her side and holding a jar of mother-in-law’s tongue; also in common between the two paintings are the zigzag border of the two women’s aprons and both wearing a cameo brooch.

However, what stands out prominently in this painting is thestoic, impassive expression of the two human figures, a man and a woman with no feelings and a blank stare. Perhaps Wood had mixed feelings about the “typical” people of rural America? Or did he want to give concrete expression to humble people who passively accept the course of life?

It was precisely the depiction of those two people in those terms that triggered considerable criticism from both art critics and the citizens themselves. As mentioned earlier, the painting was accepted at the annual exhibition of American paintings organized by the Art Institute of Chicago and won the bronze medal in the Norman Wait Harris Prize with a cash prize of $300. In November 1930 it was purchased by the institution, where it is still kept today. After the prize, the image of the painting began to circulate in the newspapers, at which point a negative reaction was triggered from Iowans, who were offended at being portrayed with that somber expression, antiquated, backward, thin-skinned, grim, and fundamentalist Puritans. Critics interpreted the work as a satire on the backwardness of Midwesterners. Wood specified in a 1941 letter that he did not intend this painting as a satire, that he did not want to caricature the inhabitants, but “the people who are offended by the painting are those who feel they resemble the subjects portrayed.” American Gothic was meant to be an image that embodied the Puritan ethos and virtues that positively characterized rural America; it was meant to offer apositive image of the values of that America with a vision that would reassure at the onset of the Great Depression.

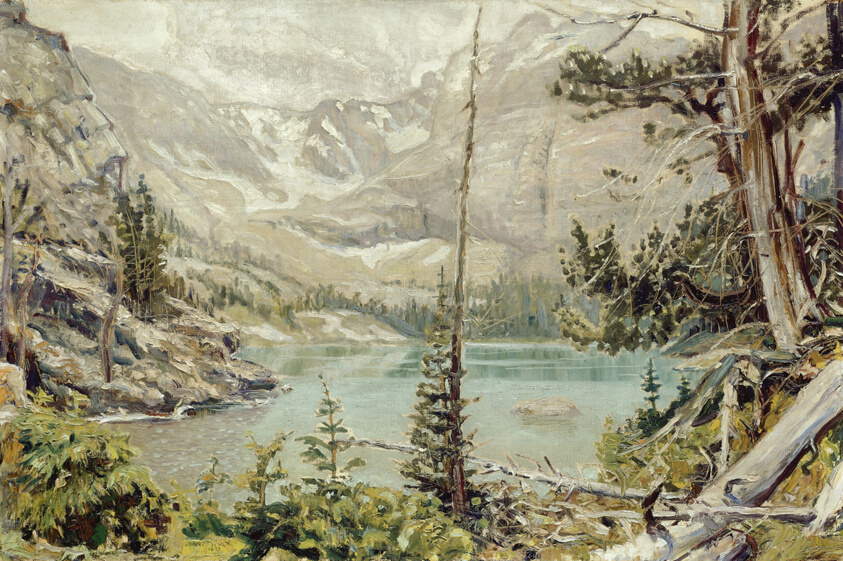

The depiction of the two characters in American Gothic was probably influenced by Northern Renaissance painting, particularly German, since in 1928, thus two years before he made the famous painting, Grant Wood had made a formative trip to Germany, to Munich, which led him to abandon the Impressionist style he had studied in Europe at the beginning of his career and to which he had felt closest up to that point (an example is Loch Vale also preserved at the Art Institute of Chicago) in order to move closer to a sharper, more realistic, more detailed and at times more hieratic painting, especially in terms of subjects. Along with Thomas Hart Benton and John Steuart Curry, Grant Wood is considered one of the exponents of American Regionalism, an art movement that developed in America in the 1930s and part of the 1940s that favored figurative and local subject matter, offering scenes of the rural Midwest and American folklore, a realistic style and subjects that were well recognizable as “typical” people from that specific region and local places. As a young man, he enrolled in the Handicraft Guild in Minneapolis, then in the School of the Art Institute in Chicago, learned metalwork, but after visiting Europe several times for a glimpse of modern trends, he rejected them, and back in America, in Iowa, he realized that American art needed to express its traditions and depict its places and people.

In addition to being one of the most famous American paintings in the world, American Gothic has also become one of the most parodied. Sarah Kelly Oehler argues that this is due in part to the initial controversy that sparked the painting when it began circulating in newspapers, but that it certainly has to do with the composition of the work itself and the way the artist painted the human figures in such a close and, above all, emotionless manner. “My theory,” he says, “is that their stoic expressions-their faces are really blank-open the door to the parody of this painting. But more importantly, this painting has come to represent a certain perspective of American values.” “Eventually, this painting became a site of social criticism-it can be transformed in so many ways, using celebrities we recognize or just different kinds of people-as a way to tap into broader questions about American society, politics, history, and so on. The painting was already famous, and these parodies continue to keep it famous and relevant,” the scholar concludes. Indeed, if you do a quick web search, you really do see all kinds, from Simpsons to Minions, from cats to a wide variety of animation characters, from political figures, including Trump, to musical stars. It was even referenced by Disney in Beauty and the Beast. And it also inspired Gordon Parks, among the most famous photographers who documented African-American life in the 20th century: in fact, in 1942 he reinterpreted Grant Wood’s painting in a photograph to which he gave the same title, American Gothic, in which he had Ella Watson, an African-American cleaning woman at the Farm Security Administration in Washington, pose holding a mop and broom in front of the flag of the United States of America.

And so that man and woman painted by Wood can become any other subject or character and the picture ever more relevant. Who knows what the artist would think of this continuous evolution of his work.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.