Amedeo Modigliani. A controversial myth

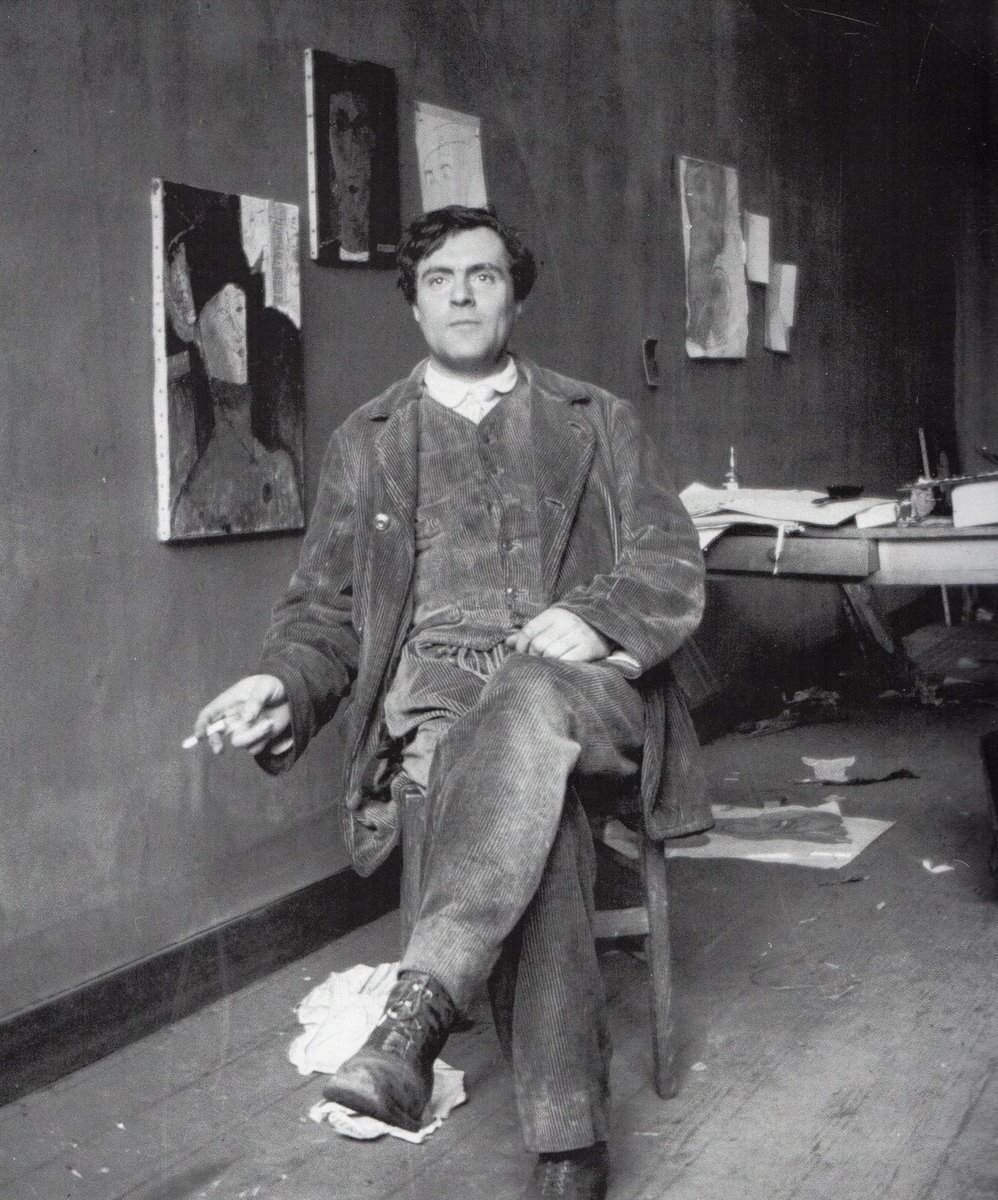

“Amedeo smiles, squeezed into a velvet jacket. He is beautiful, likeable, an actor” (Dan Franck). The photograph, taken in 1918 by Paul Guillaume, one of the first and largest art dealers Amedeo Modigliani (Livorno, 1884 - Paris, 1920) met in Paris, is the best-known image of his artist friend. “A long scarf follows him like a trail. He sits down in front of a stranger, pushes the cup and saucer away with his long, nervous hands, pulls a notebook and pencil out of his pocket, and begins to draw a portrait without even asking permission. He signs. He peels off the paper and proudly holds it out to his model. This is how he drinks, this is how he eats.”

Many years later, in 2004, to writer Dan Franck he is more of a cursed artist, a penniless Italian who leaves for Paris to make his fortune. So many more will be the exhibitions, books or catalogs that will repurpose the stereotype (sometimes, however, with hard data) of a bohemian Modigliani who uses hashish or lingers in alcohol. It is no accident that his biography, traced partly within smoky contours, partly with knowledge, ends in a short and mocking fate. Followed, moreover, by a series of dramas and the suicides of his women, first Beatrice Hastings and then Jeanne Hebuterne, his wife and model who threw herself, pregnant, from a window of her father’s house the day after the artist’s death. Yet the real “Modigliani curse” is one of which he is the victim. As is often the case, legend and tragedy mix to the point of losing track of objectivity when it comes to great figures, such as Caravaggio or Van Gogh, especially when it comes to “Modì.” Therefore, it is difficult to be able to distinguish the real quality of an artist from his tormented existential story.

|

| Amedeo Modigliani in his studio, 1915 photograph by Paul Guillaume |

|

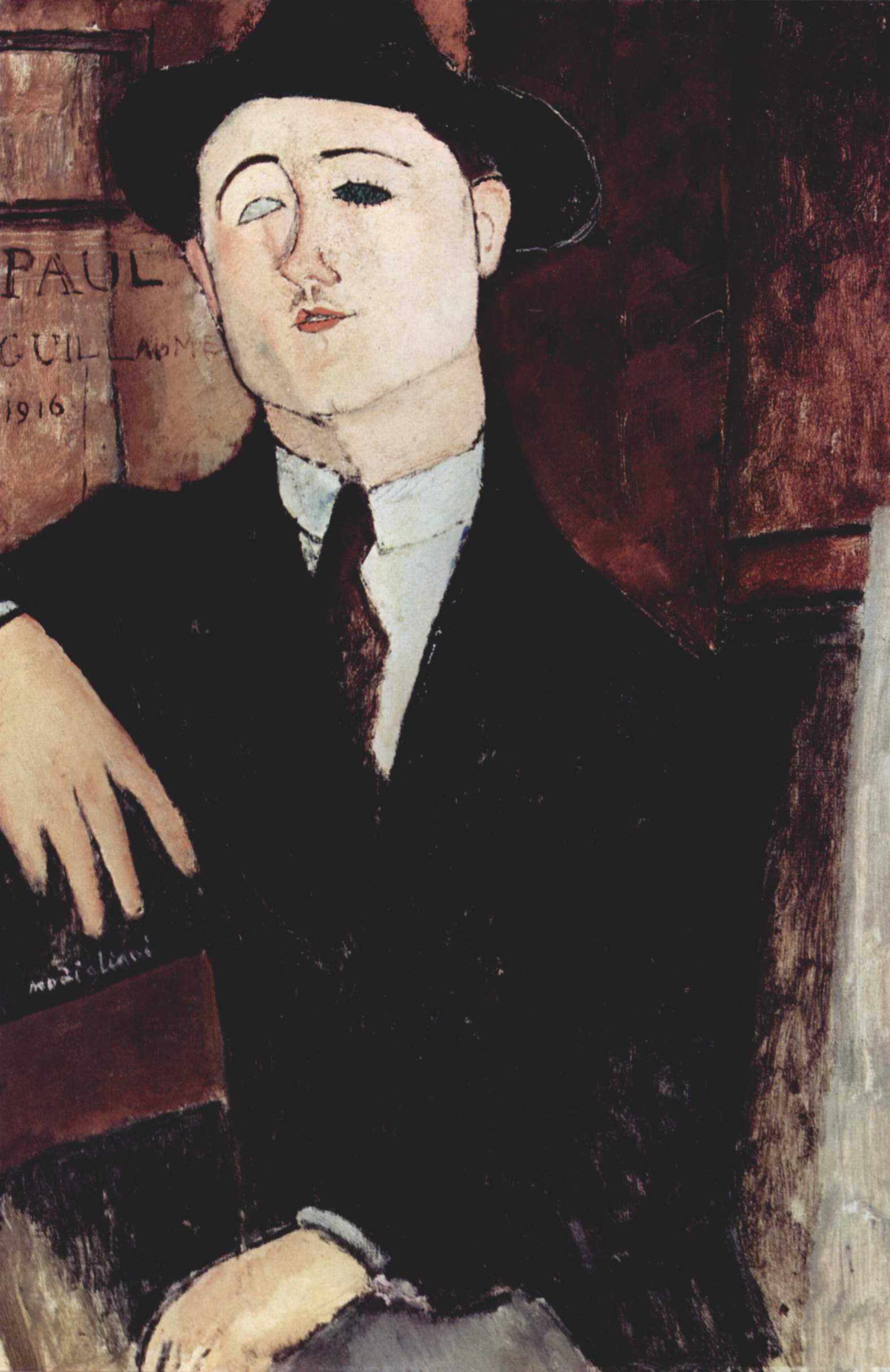

| Amedeo Modigliani, Portrait of Paul Guillaume (1916; oil on canvas, 81 x 54 cm; Milan, Museo del Novecento) |

The Leghorn artist is no exception. A thousand reasons underlie his myth: many must be ascribed to prejudices, to the need to force him into the label of the cursed artist as well as to the oddities that have often vitiated judgment, denying the intrinsic value of the work, cutting him off from the prominent personalities of the early twentieth century for a long time . This narrative, made up of false myths, has at times supplanted scientific and accurate investigation, and this in spite of the numerous investigations, between breakthroughs and denials, that have followed one another: from the affair of the discovery in 1984 of the three heads in Livorno, to the archiving of the case in 1991, from the events in Palermo with the alleged forgery of works, to the more recent case in Spoleto. For some time now, doubt has crept in about the catalog of works and the motivations behind movements of them and exhibitions dedicated to Amedeo Modigliani. What’s more, whenever he is mentioned, controversy rages in the newspapers, dozens of articles written by scholars and critics denying the signature and authorship of some works still in circulation. There is often talk of “fakes” that would roam the art market under his name. There is, in fact, not only the case of the drawing with the Seated Woman, seized last year in Rome or that of the pieces exhibited at the exhibition (opened two years ago and immediately closed), at Palazzo Ducale in Genoa, even on the drawing of the Femme Fatale released for the first time after seventy years at the 2018 Spoleto exhibition, there are strong suspicions. All these episodes are now so frequent that one can, with good reason, speak of an “obsession with Modigliani fakes,” if not even of a real “Modì Affaire”: to explain a paradox that affects a towering figure who, almost one hundred years after his death, finds no peace, shaken by continuous scandals, alleged attributions of paintings, bogus diagnostic expertise and preconceived ideas. Valid reasons are therefore to bring the whole Modigliani affair back to light, framing it with as much rigor and care as possible. There are to be kept in mind, first of all, the place of honor he occupies in the collections of the world’s major museums (the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris, the Tate Gallery in London, the Pinacoteca di Brera) as well as among the ranks of major collectors (Roger Dutilleul, Georges Menier, Jonas Netter and Paul Alexandre), and then the special place he finds in the hearts of the general public.

But although he is much loved, sought after by art dealers, and his paintings reach dizzying quotations, Amedeo Modigliani has too long remained on the margins and has been repeatedly excluded from that circle of artists, such as Picasso and Derain, who, after Cézanne, represented the incunabulum of modern art. Why? Blame an ad hoc construction of a myth easy to decant into blockbuster exhibitions? Or must responsibility lie with academic circles? Official studies, until recently, had overlooked him, regarding him as a minor, simple painter and finding his forms repetitive: he was thought to lack a real innovative charge. Blinded not only by the heated diatribes that animated (and, as we have seen, still animate), the vexata quaestio of theauthenticity of his works also appears intimidated in expressing definitive opinions: scientific research has risked being paralyzed, when not entangled in the web of anecdote or, at best, uncertainty. The doggedness of some scholars, and also the exhibition at the Tate Gallery in London (2018), have contributed to trying to settle the issue more precisely. Keeping the artist away from the mythical aura that had hitherto surrounded him, all have restored his depth, reconstructing his brief parabola within a scenario more adherent to the truth.

|

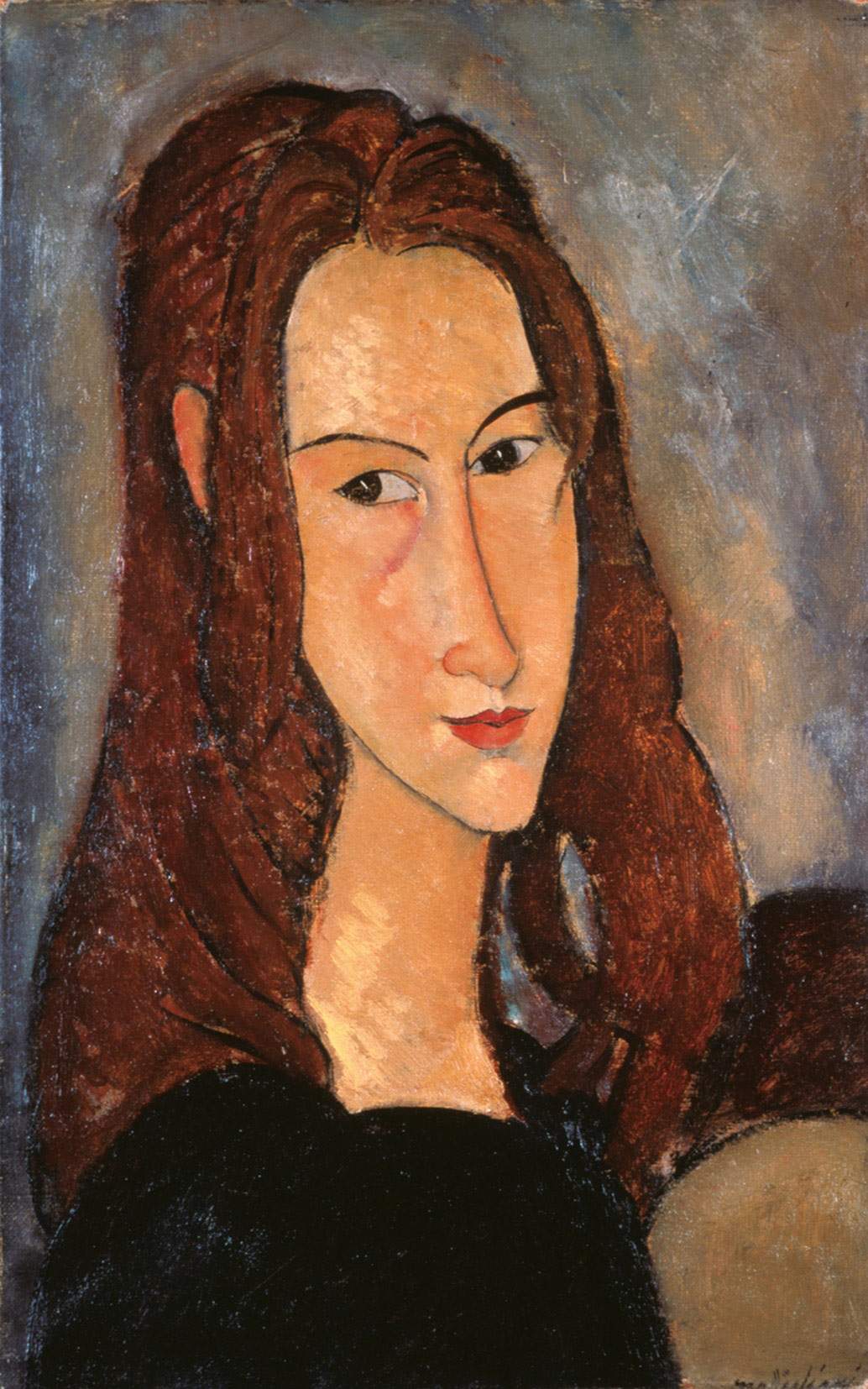

| Amedeo Modigliani, Jeune fille rousse (Jeanne Hébuterne) (1918; oil on canvas, 46 x 29 cm; Jonas Netter collection) |

|

| Amedeo Modigliani, Portrait of Jeanne Hébuterne (1919; oil on canvas, 91.4 x 73 cm; New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art) |

|

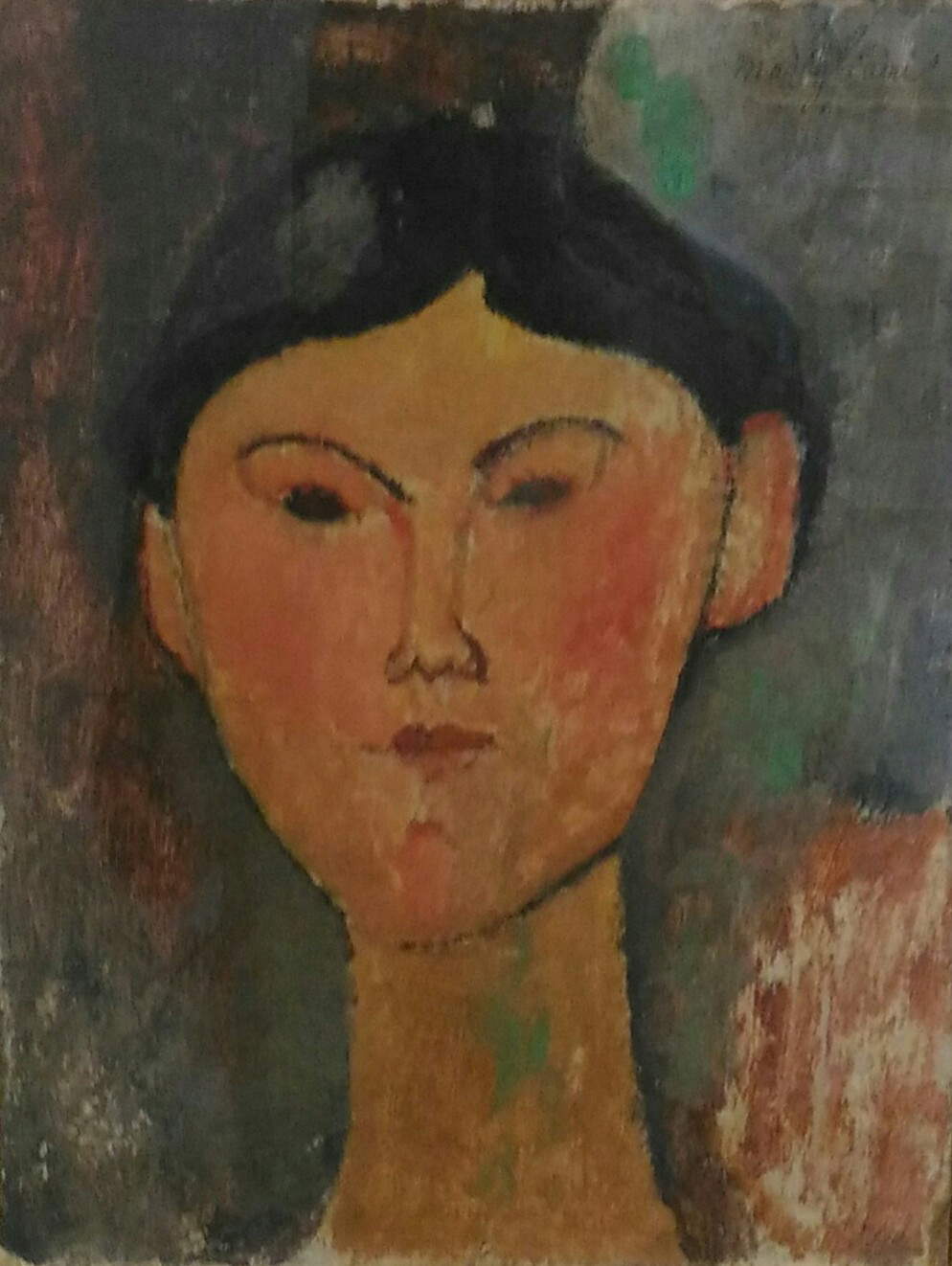

| Amedeo Modigliani, Portrait of Beatrice Hastings (1915; oil on canvas, 43 x 35 cm; Milan, Museo del Novecento) |

|

| Amedeo Modigliani, Seated Nude (Beatrice Hastings?) (1916; oil on canvas, 92 x 60 cm; London, Courtauld Gallery) |

The story of Amedeo Modigliani spanned two nations, Italy and France, and took place in a very complex period of European history. At the turn of the short century, when, in a handful of years, a series of events were looming that were tragic in their consequences: the Sarajevo bombing and theDreyfus affaire marked the end of the BelleÉpoque, and anticipated the turmoil already underway, leading to the outbreak of World War I and the rise of totalitarian ideologies. Modigliani was Jewish (as some of the symbols carved into the sandstone heads also reveal), and as a young man in his hometown he had taken up spiritualism, alchemical principles, and the Kaballah. He was an artist stubbornly in search of pure form: first, in the expression of head-only sculpture, then in the almost exclusive painting of portraits, often of his friends and beloved women.

“Modigliani’s career is the story of a long reflection of and on the human face” (Claude Roy). He initially trained in Livorno in the workshop of Guglielmo Micheli, where he also met Oscar Ghiglia. Here, prompted precisely by the master’s advice, he set off oncontinual trips to Italy: Venice, Rome, and especially Florence, to study at the Free Academy of the Nude, see Masaccio in the Brancacci Chapel and Tino da Camaino’s sculptures at the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo. But he also goes to Pisa, on the trail of Buonamico Buffalmacco’s frescoes. Soon, from 1906, he feels a strong call from the lights of Paris, where he will reside with long stays and the final stay until his death from typhoid fever in 1920 at the Hospital de la Charité.When he arrives in the Ville Lumière, he initially settles in Montmartre, rue de Calaincour, near the sites of Pablo Picasso (a former piano factory). It is the year of the Demoiselles d’Avignon, 1907, but before everyone (artists, musicians, writers), moves to the Montparnasse district, Modigliani, not far from where Brancusi works, stays at the Cité Falgiuère, a “miserable hole inside whose courtyard, [he makes] nine or ten heads.” And it seems that he sometimes “arranged his sculptures-inspired by African art but also by that of ancient Egypt, Kmer sculpture and even Italian Gothic Classical sculpture-in such a way as to make them look like elements of a primitive temple” (Gloria Fossi).

|

| Amedeo Modigliani, Caryatid (1911-1912; oil on canvas, 77.5 x 50 cm; Düsseldorf, Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen) |

|

| Amedeo Modigliani, Portrait of Léopold Zborowski (1916; oil on canvas, 100 x 65 cm; São Paulo, Brazil, São Paulo Museum of Art) |

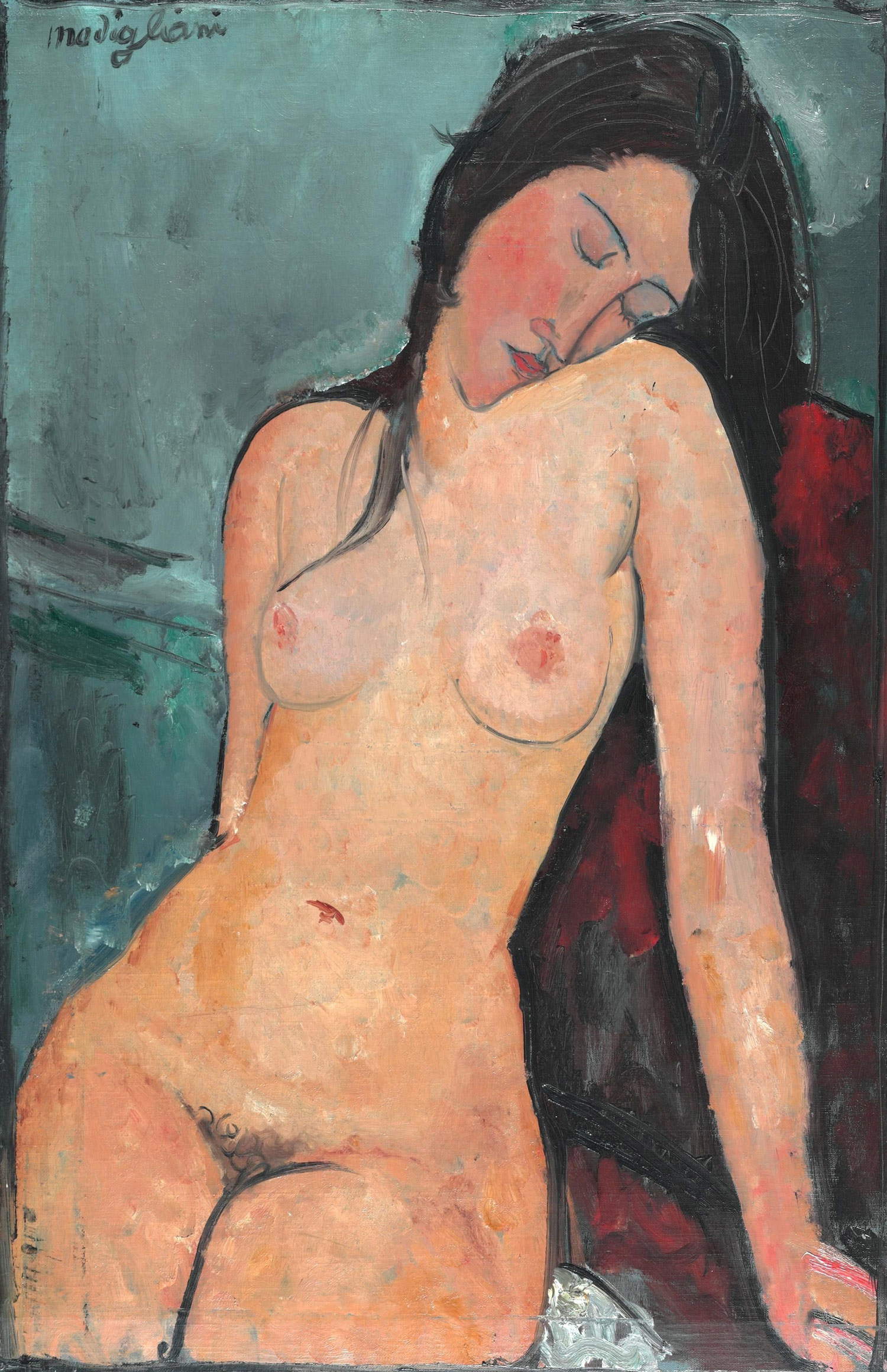

That is why it is said that he would sometimes light a candle over each one.In the new neighborhood he would frequent the rue Delta community, directed by Maurice Drouart and created by the doctor Paul Alexandre (his first patron, and one of the first to get him hashish). Here he met Marc Chagall and Chaïm Soutine, an artist who would become his great friend and protégé. These are hectic years, years of “artificial paradises” and enlistments. Apollinaire goes to war, many will not return, however, Picasso remains in town, as Spanish is neutral, and Modì remains reformed due to health problems. Over the years, from Paris to London, New York and Zurich, there were few lemonstrations, twelve in all, and only one solo show, at the Berthe Weill gallery in 1917. Organized by his friend and patron Leopold Zborowski, it was to be, because of the presence of nudes, immediately closed. Why only one exhibition? Modigliani died at age thirty-six, shortly after the end of World War I, plus these were years that facilitated group exhibitions: even Picasso and Matisse, in those years participated only in group exhibitions. But Modigliani should also be reconsidered as a careful connoisseur of art, and not only of Italian art, but also of non-European art. Models and forms of so-called “primitivism” or “art nègre” had a strong influence on his work, an influence, however, that he regenerated with his own research. “At that time,” writes Anna Achmatova, friend and poet, “Modi was raving about Egypt [...] it is clear that it was his last infatuation [...]. He said, ”Les bijoux doivent etre sauvages,“ referring to my African pearls, and he portrayed me with that necklace. ”In his works-Modigliani-reveals and conceals, removes and enhances, seduces and appeases. This eclectic, deeply inspired aristocrat, socialist and sensual at the same time, using the craft techniques of the Ivory Coast and the style of Byzantine icons, Gothic art and pluribus, creates a palpitating Modigliani. "

His precise research on line, elongated forms, and the exaggerated construction of the portrait made him one of the leading artistic personalities in those years, particularly for a perennial form of experimentation. “The prolongation of the image, excessive in the face of natural measures,” Lionello Venturi wrote of him, “was the essential necessity of a taste that contained in itself the antithesis to depth and surface, of the constructive and the decorative.”

His style, albeit with sometimes imperceptible transitions changes constantly, from the initial study of sculpture (his true passion, as he confided to his friend Ortiz de Zarate in 1903, in Venice) to the abandonment of this in favor of painting. A changement de pas due not only to the damage that the dust of the materials did to his already precarious health, but because he was pushed by his dealers, as they considered painting a more remunerative activity. His poetics from then on would be exclusively devoted to painting with the use of a palette that concentrated, in addition to the predominant use of lead white, revealed by X-ray diagnosis, in three or four other tones: chrome or cadmium yellow, yellow ochre, vermilion red, green earth and Prussian blue. All colors diluted with linseed oil so as to reduce the time it takes for the colors to harden. “If he deforms all caught up in the desire to achieve grace, if he sacrifices in order to create, and if nothing interests him except the choice of color after rhythm” (Francis Carco).Herein lies his secret along a little more than four hundred works, in the architecture of movement that subordinates the lines of the narrative and pushes it toward myth.

Reference bibliography

-

Bibliography:

- Annette King, Nancy Ireson, Simonetta Fraquelli, Joyce H.

- Townsend, The Modigliani technical research study, in The Burlington Magazine, CLX, 1380 (March 2018)

- Gloria Fossi, Amedeo Modigliani in London .

- Three Heads and a Beggar ,

- in Art and Dossier (February 2018), Giunti, pp.36-43

- Enzo Maiolino (ed.), Modigliani dal vero .

- Unpublished and rare testimonies collected and annotated by Enzo Maiolino, De Ferrari, 2016

- Giorgio Cortenova (ed.), The Seventh Splendor .

- The Modernity of Melancholy, exhibition catalog (Verona, Palazzo della Ragione, March 25 to July 27, 2007), Mondadori, 2007

- Dan Franck, Montmartre & Montparnasse .

- La favolosa Paris d’inizio secolo, (original title Bohémes), Garzanti Elefanti, 2004

- Marc Restellini, Amedeo Modigliani .

- Langelo dal volto severo ,

- exhibition catalog (Milan, Palazzo Reale, from March 20 to July 6, 2003), Skira, 2003

- Alfred Werner, Modigliani, Garzanti publisher, 1990

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.