by Federico Giannini (Instagram: @federicogiannini1), published on 26/08/2018

Categories: Works and artists

- Quaderni di viaggio / Disclaimer

A reading of Ambrogio Lorenzetti's Maremma works following the Massa Marittima exhibition and with particular reference to their political meanings and iconographic novelties.

The recent exhibition Ambrogio Lorenzetti in Maremma. Masterpieces from the Territories of Grosseto and Siena, at the Complesso Museale di San Pietro all’Orto in Massa Marittima until September 16, 2018, made it possible to focus attention on theMaremman activity of one of the greatest protagonists of the European fourteenth century, Ambrogio Lorenzetti (Siena, ca. 1290 - 1348). If among the general public his great Sienese masterpieces are best known, starting with the frescoes of theAllegory of Good and Bad Government, the same cannot be said for the marvelous and fundamental works by him that are preserved in the current province of Grosseto: the Massa Marittima exhibition, a sort of “miniature” re-proposition of the great Sienese monograph of the winter of 2017-2018 (the first ever dedicated to Ambrogio Lorenzetti), so much so that it was curated by the same scholars (Alessandro Bagnoli and Roberto Bartalini: in Massa Marittima, only Max Seidel, the third curator of the Santa Maria della Scala exhibition, was absent), allowed the public to focus precisely on the Maremma enterprises, not least because the exhibition expanded to involve the other immovable evidence of Lorenzetti’s painting in the city.

However, accurately reconstructing Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s activity in Maremma is not an easy task, since there are few certain testimonies on which we can rely. In the period in which Ambrogio Lorenzetti lived and worked, a large part of the Maremma was under the direct dominion of Siena, which had already subjugated the city of Grosseto and its immediate surroundings towards the middle of the 12th century, and since then had never put an end to its expansionism, whose aims aimed at the very rich Massa Marittima, a flourishing independent commune at the center of an important mining district. Thus, between the end of the thirteenth century and the beginning of the following century, after having consolidated its territory and having found an outlet to the sea by annexing Talamone and the surrounding area and acquiring its territories from the monks of Santa Fiora, the Republic of Siena was first able to incorporate into its dominions some strategic centers, such as Roccalbegna and Roccastrada, and in 1333 it succeeded in officially extending its dominion over Massa Marittima, which submitted in 1335, thus sanctioning the end of its centuries-old independence. For the town thus began an inexorable decline, which began with the transfer of most of its entrepreneurial class to Siena, accelerated with the plague of 1348, and made definitive with the reduction of mining activity.

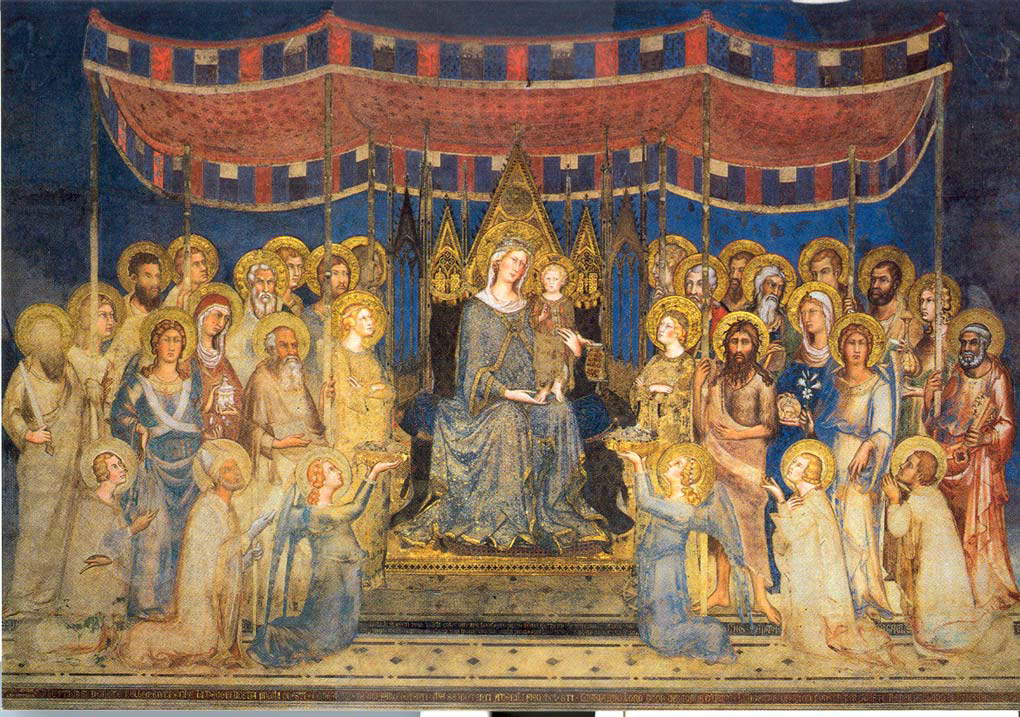

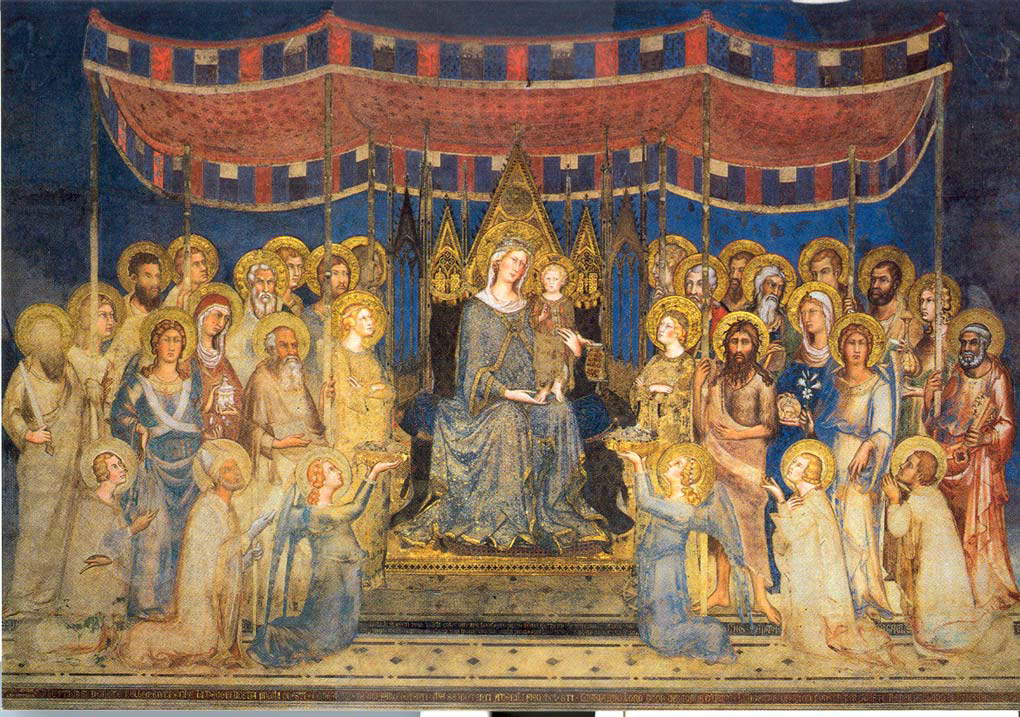

It is precisely from the fateful 1335 that it is possible to begin to better frame Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s role and works in Maremma. It is necessary, however, to premise that his presence in Massa Marittima is attested by ancient sources: both Lorenzo Ghiberti (in the Commentarii) and Giorgio Vasari (in the Lives) recall that Ambrogio painted a panel and the fresco decoration of a chapel in Massa Marittima. Ghiberti states that “he is at Massa a large panel and a chapel,” and Vasari echoes him by claiming that “at Massa working in company with others a chapel in fresco, and a tempera panel, he made known to those how much he of judgment and wit in the art of painting was worth.” If it is rather complicated to identify which frescoes were painted by Ambrogio Lorenzetti in Massa Marittima (we will return to this subject below), it is easier to identify the panel, which can be indicated without doubt in the great Madonna and Child Enthroned with Theological Virtues, Musician Angels, Saints and Prophets, but more simply known as the Majesty of Massa Marittima, the great protagonist both at the Siena exhibition and at the show that was set up around it in its current “home,” the Museum of Sacred Art in the San Pietro all’Orto Museum Complex in Massa Marittima (the show was in fact held in the room that usually houses Lorenzetti’s large panel, in the adjacent room and in a room on the lower floor).

In their essay in the catalog of the Santa Maria della Scala exhibition, Max Seidel and Serena Calamai hypothesized a fundamental political role for the Maestà , chronologically placed precisely in the period when Massa Marittima was conquered by Siena. Made certainly before 1337 (the hypothesis is put forward on the basis of stylistic evidence), the panel is placed in the years immediately following the subjugation of Massa Marittima to Siena, which with the Majesty of San Pietro all’Orto sanctioned also in “artistic” terms its domination over the Maremman city and the political and cultural bond that united them. The iconographic theme of the Majesty, adapted to the context of Massa Marittima (in the foreground, in fact, the figure of St. Cerbone, the patron saint of the city, can be seen: he is the first on the right), was chosen by the Augustinian hermits who, from the end of the 13th century, managed the church of San Pietro all’Orto. The Augustinians, “sensitive to contacts with temporal powers,” Seidel and Calamai write, “had appropriated the symbol of the city of Siena, the Majesty, by translating the political theme of Duccio’s and Simone Martini’s precedents into a more intimate iconographic form that nevertheless went with the taking over of the city by the Government of the Nine.” This was a way of affirming, in an extremely representative way, “the combined inclusion of the hermit order of St. Augustine and the Sienese government [to which the hermits were very close, nda] in the new city of Massa.” In this sense, the proximity in the work of Saints Cerbon and Augustine, painted alongside each other, and the iconography of the Majesty, which “increasingly appears as a symbolic interpenetration of Sienese power with the complex theological and iconographic texture of the Augustinians,” should be read.

|

| A room of the exhibition on Ambrogio Lorenzetti in Massa Marittima. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| The Republic of Siena between the 15th and 16th centuries. From Ettore Pellegrini, The Fall of the Republic of Siena (NIE, 2007). |

|

| Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Madonna and Child Enthroned with Theological Virtues, Musician Angels, Saints and Prophets, also known as the Massa Marittima Majesty (c. 1335; gold, silver, lapis lazuli and tempera on poplar wood panels, height 161 cm the central panel, 147.1 the side panels, width 206.5 cm; Massa Marittima, Museo dArte Sacra) |

Beyond its strong political significance, the work is in fact nourished by important religious foundations. At the center of the panel is the Madonna holding the Child in her hands and seated on a highly original immaterial throne that has for its base the three colored steps of the theological virtues, for its seat the large scroll-like cushion supported by the angels, and for its back the wings of the latter. On the three steps of the throne sit the allegories of the three virtues: Faith(Fides, white, to emphasize the whiteness of faith according to an iconography that goes back as far as Horace’s Odes ), which holds a mirror in which the face of the Trinity is reflected (an invention of Lorenzetti, who introduced the Speculum Fidei on the basis of Augustinian readings: the mirror, a symbol that goes back to the letters of St. Paul, is an allegory of divine revelation, which is shown to the faithful), Hope(Spes, green), who holds a tower in her hands (for St. Augustine, hope is “turris fortitudinis,” “tower of fortitude,” in that hope is animated by such a feeling that drives it to desire the highest good, and the color green is associated with the vitality necessary not to lose sight of the end to which hope tends), and Charity(Caritas), red like the fire of passion that animates charitable gestures, whose symbols, in accordance with Augustinian theology, are a heart and an arrow (“Sagittae potentis acutae verba dei sunt. Ecce iaciuntur et transfigunt corda; sed cum transfixa fuerint corda sagittis verbi dei, amor excitatur,” or “God’s words are powerful and sharp arrows: behold they are shot and pierce hearts, but when hearts are pierced by the arrows of God’s word, love is stimulated.”) The chromatic representation of the three virtues in the Majesty of Massa Marittima also follows literary suggestions from Dante. In fact, Dante Alighieri, in Canto XXIX of the Purgatorio, described the appearance of the theological virtues in the following way: “Three women around, from the right wheel / came dancing: one so red, / that barely pierced inside the fire known; / the other was as if the flesh and bones / had been made of emerald; / the third seemed to be snow testè mossa.” Not only that: one can also catch references to Jacopone da Todi (“Amor, che sempre arde / fa’ le lengue darde / che passa onne corato”), who in his Laudi provided a more accessible vernacular form to St. Augustine’s Latin reflections on charity. And Ambrogio Lorenzetti drew inspiration from it to depict the allegory of charity as no one before him had done. A pure, transparent, beautiful charity (“caritas est animae pulchritudo,” wrote St. Augustine: “charity is the beauty of the soul”), modeled from the cues of patristics to result in the definition of the image of a “sacred Venus,” whose beauty, Seidel and Calamai state, “is represented by the uncovered shoulder, by the roundness of the breasts enhanced by the flow of light on the chlamydia of the robe in the antique style, which derives from the reliefs of Roman sarcophagi,” but whose physicality is at the same time rendered ethereal by Ambrose’s “light painting.” “the emanation of light in the bodily transparency is rendered with fine red brushstrokes which, for greater concentration of heat, are most intense in the concavity of the turning of the neck and define the outlines of the eyes, nose and slightly ajar mouth.”

The theme of charity is of central importance in Lorenzetti’s panel: not only is the character of Caritas closest to Our Lady, but the Virgin herself loses that hieraticism that, to some extent, still distinguished her in Simone Martini ’s Majesty in the Palazzo Pubblico, to become a Mater Misericordiae who gives a tender kiss to the Child (an iconological reference to a passage in St. Bernard in which the kiss between Our Lady and her son is an allegory of the union between Christ and his Church) and who refers back to an earlier work by Duccio di Buoninsegna, the Madonna of Charity now in the Kunstmuseum in Bern. The assumptions of such an iconography, Seidel and Calamai write again, rest on medieval texts that identify the Madonna as a “sweet and loving mother.” for example, a 13th-century author, Richard of St. Lawrence, asserted that “Charitas eius charitatis omnium sanctorum forma est et exemplar” (“Her [i.e., Mary’s] charity is the model and example of charity for all the saints”), and Ambrogio Lorenzetti may have had similar passages in mind when he thought of depicting, on a single axis, charity, the Madonna and God (who, as per tradition, was probably located in the lost central pinnacle of the complex). This “transformation” of the Madonna, however, does not conclude the list of iconographic innovations that Ambrogio Lorenzetti, a highly original painter of extraordinary talent, introduced into his work. Observe the angels at the Madonna’s sides: in Simone Martini (and before that in Giotto, particularly in the Maestà di Ognissanti) they were kneeling at the Virgin’s sides and raising vessels filled with flowers toward her. In Ambrose, on the contrary, the angels offering flowers are standing, and even ideally exceed the height of the Madonna, so much so that they must lower their gaze to reverence her: an element that the Sienese artist probably included to reinforce the allegorical message of the angels (not least because their gestures appear much more concise), mediators between the faithful and the Madonna.

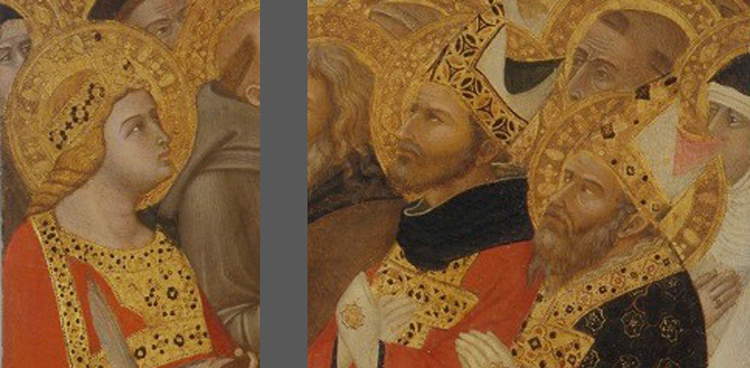

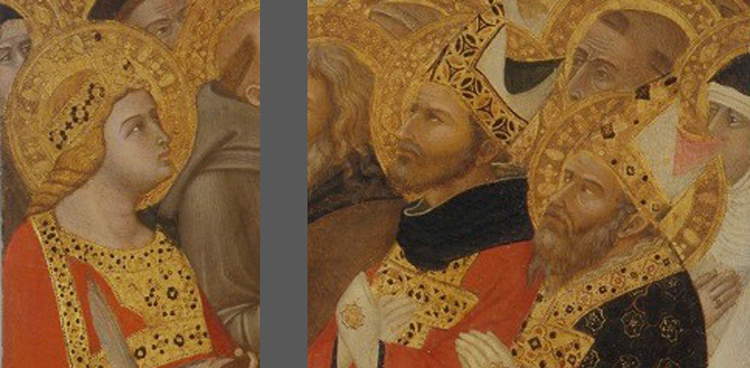

Several other innovations Ambrose included in his work. Moving downward, note the musician angels at the foot of the throne, each bearing a different musical instrument (two vielle the angels in the foreground, a psaltery the angel in the background on the left, a zither the one on the right). Ambrogio Lorenzetti decorated the haloes of the angels in the foreground with punched open wings, and those in the background with closed wings, wanting to make explicit the connection of the former with the angelic hierarchy of cherubim, and of the latter with seraphim (the angels closest to God). It is a kind of celebration of music according to St. Augustine, who in a passage of his Enarrationes in Psalmos spoke precisely of the psaltery and the zither as instruments symbolizing the word of God: the former is concave upward, and thus symbolizes heaven, the latter downward and is therefore an allegory of the earth (and the word of God comes from heaven but is addressed to the earth), so the instruments deemed in a certain way closer to God are played by the angels who are also closer to divinity. Other suggestions are drawn from observing the figures of the saints (all, moreover, individually connoted): St. Augustine (clad in the black robe of hermits under bishop’s vestments) placed next to St. Cerbon, patron of Massa Marittima, could rise, Seidel and Calamai suggest, as a symbol of that vita perfectissima which for the German hermit Henry of Friemar (Friemar, c. 1250 - Erfurt, 1340) was substantiated as much in dedication to contemplation of God as in an active and committed life. So, St. Augustine next to St. Cerbon becomes a political symbol of the hermits who “leave” the convent to put their commitment at the disposal of the city of Massa Marittima. A message reinforced by the presence, on the opposite side, of St. Catherine of Alexandria, a saint whose great wisdom was praised, and thus a symbol of study and knowledge, qualities indispensable for an active life.

|

| Majesty of Massa Marittima, the three theological virtues |

|

| Majesty of Massa Marittima, the Faith |

|

| Majesty of Massa Marittima, Hope |

|

| Majesty of Massa Marittima, Charity |

|

| Majesty of Massa Marittima, the Madonna, Child and angels |

|

| Duccio di Buoninsegna, Madonna of Charity (ca. 1290-130; tempera on panel, 31.5 x 22.5 cm; Bern, Kunstmuseum) |

|

| Simone Martini, Majesty (1315; fresco, 763 x 970 cm; Siena, Palazzo Pubblico) |

|

| Giotto, Majesty of All Saints (c. 1310; tempera on panel, 325 x 204 cm; Florence, Uffizi) |

|

| Majesty of Massa Marittima, Saint Catherine of Alexandria, Saint Augustine and Saint Cerbon |

|

| Majesty of Massa Marittima, the musician angels |

|

| Majesty of Massa Marittima, the musician angels |

The discovery of the Majesty of Massa Marittima, of which there was no more news as early as the 16th century, moreover, occurred in a rather daring way: the merit is attributed to a teacher, Stefano Galli, a Romagnolo but Massetano by adoption, a scholar of local history as well as the first director of the Library of Massa Marittima, who found the Majesty in 1867, in an attic of the convent of Sant’Agostino, adjacent to the church of San Pietro all’Orto whose structure, precisely in those years, was being profoundly distorted (the church in 1866 had in fact become the property of the state, which turned it into a school, completely altering the building, which had already, however, been heavily and clumsily renovated during the 18th century). The table, at the time of its discovery, was in a very poor state of preservation: it was divided into five pieces, along the boards of the compartments, and tradition has it that Galli found it being used in a room used as a charcoal pile as a support for stacking coal to be used for heating the rooms of the former church building. Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s masterpiece thus underwent an initial restoration, and another intervention it would undergo in 1978, before its transfer to the Palazzo di Podestà in Massa Marittima and its definitive musealization in 2005, with its entry into the Museum of Sacred Art.

Equally “adventurous” was the discovery of another Maremma work ascribed to the hand of Ambrogio Lorenzetti, again in Massa Marittima and again in San Pietro all’Orto. It is a fragmentary fresco depicting St. Christopher with the Infant Jesus on his shoulders, found in 2003 during some works of adaptation of the former church of San Pietro all’Orto, which was about to house the collection of the Museum of Ancient Mechanical Organs. News of the fresco was already given in 1873 by the aforementioned Stefano Galli, who assigned it to Lorenzetti, although not on a philological basis, but on the basis of Ghiberti’s and Vasari’s reports that, as mentioned above, Ambrogio Lorenzetti frescoed a chapel in Massa Marittima. The work, which was later covered by a layer of plaster, unfortunately survives in only a few details: a portion of St. Christopher’s face, the Infant Jesus on his shoulder, the drapery of the latter, and part of the decoration of the frame are discernible. To see the fresco today, it is necessary to go to the Museum of Ancient Mechanical Organs: a glass pane added in 2003 at the height of the floor (the latter inserted, during the eighteenth-century interventions, at half the height of what was once the nave of the church) makes it possible to understand how far the fresco once reached. “Of the St. Christopher,” wrote Alessandro Bagnoli in the essay devoted to new evidence on Ambrogio Lorenzetti in the Siena exhibition catalog, “the enigmatic Buddha-like appearance, conferred by the long wavy cut of the left eye strongly half-closed, which is a distinctive characteristic of the Sienese master, is astonishing”: a revealing detail for assigning the work to Ambrogio, and present, almost identically, in the Majesty now preserved at the Szépm?vészeti Múzeum in Budapest. However, it is difficult to think of this Saint Christopher as a possible sole survivor of that “chapel” mentioned by Ghiberti and Vasari: given its position (on a wall near what must once have been the church altar) and the type of fresco, it is likely to have been an isolated figure. The “chapel” must therefore be looked for elsewhere.

The stylistic clues lead to the Cathedral of San Cerbone, where it is possible to advance the name of Ambrogio Lorenzetti for an Annunciation located on the wall of the left aisle: for Bagnoli, “it could be considered the mural figuration of a chapel.” Again, this is a recent find: the wall, freed from the scialbatura in a restoration conducted between 1996 and 1997, only then revealed the magnificent fresco it concealed. A fresco that today appears to us faded and worn, in a rather precarious state of preservation: nonetheless, we are able to appreciate even here Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s extraordinary inventions, starting with the half-open window that we see beside the Virgin and that the artist inserted to increase the spatial depth of his work (in turn enhanced by the indication of the light source, which comes from the left). No similar details are found in the work of any other painter of the 14th century. The attention to detail typical of the Sienese painter is also evident in the detail of the book: we see it open to the page that the Madonna was reading at the time of the angel’s arrival (and standing out solitary between the two open portions of the volume), while she, with her thumb, holds the sign to remind us how far her reading had come. There are also elements that bring the San Cerbone Cathedral fresco closer to other Lorenzettian works: Bagnoli identifies in the care with which the open page is depicted the same meticulousness that Ambrose lavished on the rendering of the same detail in theAnnunciation painted in 1344 for the Ufficio di Gabella in Siena; moreover, the decoration of the Madonna’s halo is the same as that found in the monarch appearing in the episode of the Martyrdom of the Six Franciscans frescoed in the basilica of San Francesco in Siena, and again the layout of the composition, Bagnoli again suggests, reveals affinities with that of the Public Profession of St. Louis of Toulouse (also in St. Francis in Siena) or that of the Purification of the Virgin now in the Uffizi. Is thisAnnunciation, then, the only surviving evidence of Ghiberti and Vasari’s “chapel”? Given the above elements and the importance of the place that houses it, the odds are indeed quite high.

|

| Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Saint Christopher with Baby Jesus on his shoulders (c. 1340; fresco; Massa Marittima, Museum of Ancient Mechanical Organs). Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Madonna and Child Enthroned (c. 1330-1340; tempera, gold and silver on panel, 85 x 58 cm; Budapest, Szépm?vészeti Múzeum) |

|

| Massa Marittima, Piazza del Duomo. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| The Cathedral of San Cerbone in Massa Marittima. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte. |

|

| Interior of the Cathedral of San Cerbone. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Annunciation (c. 1340; fresco; Massa Marittima, Cathedral of San Cerbone). Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Annunciation (1344; tempera and gold on panel, 121.5 x 116 cm; Siena, Pinacoteca Nazionale) |

The Maremma activity of Ambrogio Lorenzetti (and the Sienese expansionism of the 14th century) is also responsible for the Roccalbegna Polyptych, a painting originally kept in the church of Saints Peter and Paul in the village in the province of Grosseto, and which unfortunately has come down to us in fragments: in the central compartment, we see what remains of a sumptuous Madonna and Child, and at the sides Saints Peter and Paul, the titular saints of the parish church of Roccalbegna. Recent studies have reconstructed the historical moment when Ambrogio Lorenzetti was entrusted with the execution of the polyptych: Roccalbegna, a mining center part of the Mount Amiata district, located on the Albegna and Fiora Hills (the hilly area that frames the Grosseto Maremma), became part of the Republic of Siena in the 1390s, and from that period the Sienese worked to develop the settlement, completely renovating the village and initiating the construction of new buildings. These included the parish church of Saints Peter and Paul (at that time, however, dedicated only to St. Peter), completed in 1330. According to the documents of the time, the Government of the Nine (i.e., the junta that led the Republic) held the patronage of the small church in Roccalbegna, and it is therefore more than legitimate to think that it had commissioned the greatest painter of the Republic to create the polyptych that was to embellish the church, as the “crowning achievement,” explains Federico Carlini, “of a complex long-term action, which had aimed from the beginning at the integral re-foundation of the local urban identity.” The commission of the polyptych, moreover, was configured as part of the Sienese political strategy: “the works imported from Siena,” we read in a 1979 essay by Enrico Castelnuovo and Carlo Ginzburg, “were [...] an instrument of penetration of Sienese culture,” which the Republic used systematically in the most important conquered centers.

As anticipated, today the work appears lacunose (and was probably completed by other compartments), but this does not prevent us from appreciating its dimension as a “true masterpiece of Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s late maturity” (Carlini). In the center, the Madonna and Child, in a compartment resected at an unspecified time, sit on a rich throne, foreshortened from below to accommodate the viewpoint of the faithful in the church, and framed on either side by two Gothic pointed mullioned windows with two lights and closed behind by a backrest covered with a splendid fabric decorated with geometric motifs. The figures are solid and imperious (note the hieratic, serious, almost sullen gazes of St. Peter and St. Paul) and highlighted by very fine elements: this is the case with St. Peter’s liturgical vestment, and especially with his very elegant crosier (a kind of masterpiece of carving rendered in painting, with the curl mounted on a kind of Gothic temple and ending with the depiction of the Eternal Father inserted in a mandorla), but also with the brooch that stops the Virgin’s maphorion, or the very fine punches that decorate the nimbuses of the Madonna and the saints.

|

| Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Madonna and Child with Saints Peter and Paul also known as Polyptych of Roccalbegna (c. 1340; tempera and gold on panel, 86 x 72 cm the central panel, 133 x 71 cm the side panels; Roccalbegna, Church of Saints Peter and Paul) |

|

| Roccalbegna polyptych, the Madonna and Child. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s Maremma works confirm his vocation as a great civic painter, even before he was an important artist of religious icons. This dimension, which characterized much of his activity, was also recognized in ancient times. Among the first to portray Ambrogio Lorenzetti as a painter-philosopher (as well as a politically engaged artist) was Giorgio Vasari, who wrote thus in his Lives, “always practicing with literati and scholars, he was by those with title of ingenious received and of continually well regarded, and was put to work by the Republic in the public governments many times and with good degree and with good veneration. His manners were very praiseworthy, and, as of a great philosopher, his mind was always disposed to be content with every thing that the world gave him, and ’l bene e ’l male as long as he lived he endured with great patience.” An educated painter, held in high esteem by his fellow citizens (so much so that he participated actively in the political life of his city), Ambrogio Lorenzetti probably devised himself many of the iconographic innovations that he introduced in his works, without suffering passively from the choices of the theologians who pointed out to him the programs of the paintings, but participating in the first person in their definition, presumably providing cues and suggestions. And thus succeeding in updating the figurative tradition with his vast culture, which extended from literature to philosophy. These peculiarities of Ambrogio Lorenzetti were also well highlighted by both the Siena and Massa Marittima exhibitions.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.