It is not a simple work, the Badia a Rofeno triptych, one of the most interesting paintings by Ambrogio Lorenzetti (Siena, ca. 1285 - 1348) and currently housed in the Museo Civico di Palazzo Corboli in Asciano, in the historic center of the town nestled among the Crete Senesi. As fascinating as it is problematic, it is a painting on which several questions have long weighed (and, in some respects, still do). On what occasion was it executed, and for whom was it intended? In what period of Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s career can it be placed? Why do the measurements of certain parts of it appear so incongruent with the rest of the work? What is the significance of the highly unusual scene that appears in the central panel?

|

| Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Triptych of Badia a Rofeno (c. 1332-1337; tempera and gold on panel, 258 x 230 cm; Asciano, Museo Civico di Palazzo Corboli) |

|

| Ambrogio Lorenzetti, the Badia a Rofeno Triptych on its wall |

|

| Ambrogio Lorenzetti, the Badia a Rofeno Triptych in its room at the Museo Civico di Palazzo Corboli in Asciano |

A restoration, completed in 2011, helped dispel many of the doubts that hovered around the work. A restoration that had become necessary due to the conservation conditions in which the work was in between 2005 and 2006. It is necessary, however, to start from further back in time, at least from the 1940s, when the Sienese Superintendency decided to remove the triptych from the church of Saints Jacopo and Christopher of the Abbey of Rofeno, near Asciano: the building, in fact, had been built on particularly delicate and unstable ground from a geological point of view, and the continuous injuries suffered by the church had jeopardized the survival of the works contained in it. This was not a new situation: already at the beginning of the twentieth century a similar situation had arisen, which had led the then Superintendent to have the triptych removed from its location and restored. The work, however, turns up again in the abbey during the 1920s. But the tranquility of the 14th-century painting was short-lived: the work left the abbey church for good in 1941 to be sent to Arezzo, where it remained until 1952, the year of the opening of the new Museo d’Arte Sacra di Asciano (Museum of Sacred Art of Asciano), which was set up in the local church of Santa Croce and housed works of art and liturgical objects from churches in the area. Fifty years later, in 2002, the current Museo Civico in Palazzo Corboli was opened, adding an archaeological section to that reserved for sacred art: the painting was transferred to the new location, but some problems related to the building’s microclimate (later fortunately solved thanks to a program of analysis and intervention studied by the then director of the museum, Milena Pagni, the Technical Office of the Municipality of Asciano, the Superintendency and the Opificio delle Pietre Dure) worsened its conservation conditions, to the point that its restoration, the fourth in the work’s history, took place at the laboratories of theOpificio delle Pietre Dure in Florence.

The museum’s microclimatic alterations had in fact led to lifts in color that needed to be repaired, but that was not all: the wooden support needed to be restored, and above all it was necessary to understand how to deal with the 16th-century frame, attributed to the Olivetan monk Fra’ Raffaello da Brescia (born Roberto Marone, Brescia 1479 - Rome 1539), within which the triptych was later assembled. The restorers began by veiling the work, meaning they applied layers of Japanese paper to the surface in order to secure the most delicate portions prone to color loss. After spending some time in a climate-controlled environment in order for the humidity of the support to balance with that of the environment, the painting was separated from its rich carved frame and the work was moved on to restore the wooden support (the objectives were to keep the natural deformations of the wood under control, and to consolidate the support against the action of external agents) and then proceeded with a cleaning that allowed the removal of ancient repainting and materials added irrelevantly in previous restorations, and then with a necessary plastering in order to allow the next phase: Pictorial restoration, that is, the difficult and laborious reintegration, where possible, of the gaps. Painting to provide greater protection for the triptych concluded the work.

|

| The Badia a Rofeno triptych in the 16th-century frame during the glazing process |

|

| Fra’ Raffaello da Brescia, Frame of the Badia a Rofeno triptych (first decade of the 16th century, carved, gilded and polychromed wood, 258 x 230 cm; Asciano, Museo Civico di Palazzo Corboli) |

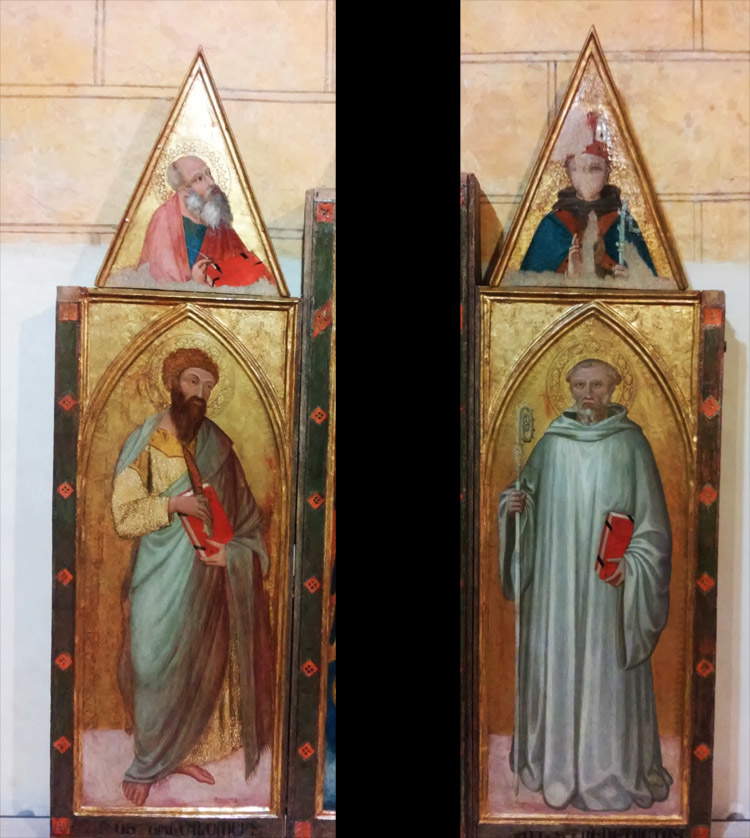

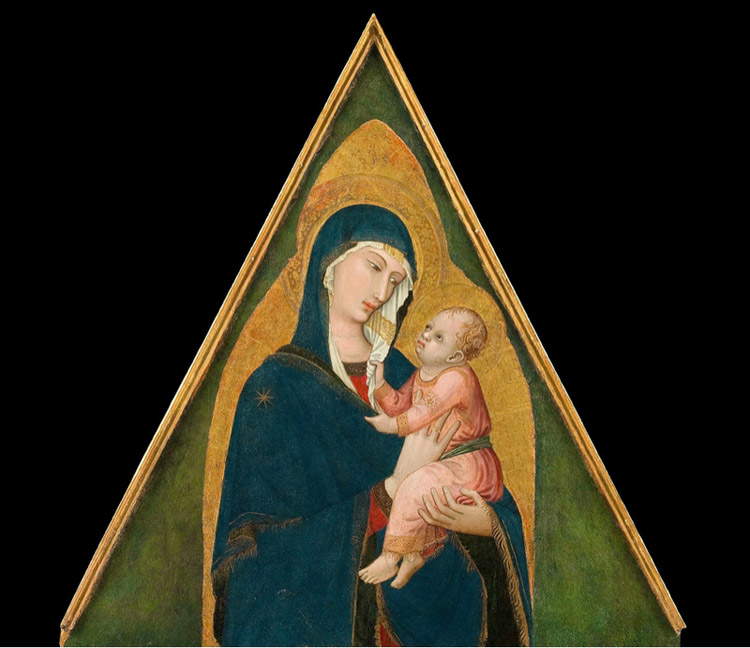

In parallel with the restoration, in-depth studies were conducted that shed light on many obscure points that were still waiting to be clarified. First, however, it is necessary to take a look at the painting, one of the most splendid and lofty examples of 14th-centurySienese painting, the work of one of the greatest masters of his century. The great protagonist of Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s triptych is Saint Michael, to whom the central compartment belongs. He is struggling against the devil, who, however, does not take on the typical features of the serpent or the dragon: he is a hideous seven-headed reptile, equipped with wings and legs; he is already succumbing in the struggle but is still alive and energetic, and the archangel is about to deal him a blow. We see him in a very energetic, vigorous, dynamic pose as he is about to forcefully drop his sword on his enemy with his right hand, his expression intense and focused. His wings are spread out and occupy the entire width of the panel, and so is his cloak, which opens in arty, refined and unnatural twirls, particularly pleasing to the painters of the Sienese school. The elegant armor is finely ornamented with decorations that almost seem to come out of a goldsmith’s workshop. On the sides, in the side compartments, we find Saint Bartholomew on the left, while on the right we meet Saint Benedict. On St. Bartholomew there is a curiosity: in ancient times a pilgrim’s staff was added to it, because at the time of the work’s transfer to Rofeno Abbey (this was not in fact its original destination) they wanted to endow the painting with the titular saint of the church in which the triptych would be placed. A staff was thus considered sufficient to transform St. Bartholomew into St. James (or St. Jacob, the variant of the name “James” particularly common in Tuscany). Finally, the upper register: in the center, instead of a more usual Annunciation or a more frequent Padreterno, we find, a unique case in Sienese art of the time, a delicate Madonna and Child, while on either side she is accompanied by Saint John the Evangelist on the left, and Saint Louis of Toulouse on the right.

Let us begin to discover the work more closely by starting with its author. For a long time, in fact, it was believed that the triptych of Badia a Rofeno was not the work of Ambrogio Lorenzetti, although the attribution to the Sienese artist has a history that begins as far back as 1912, namely when, for the first time, scholar Giacomo De Nicola, who linked the work to the compartments of Lorenzetti’s polyptych now preserved in the Opera del Duomo in Siena and depicting Saints Catherine of Alexandria, Benedict, Francis and Mary Magdalene, formulated Ambrose’s name. Yet, not everyone welcomed De Nicola’s proposal: there were those who, like Hayden Maginnis, considered it to be the work of Ambrose, but with the concurrence of the workshop, those who speculated that it was the work of his school, those who identified distinct hands, and there were even those(George Rowley in his 1958 monograph on Ambrose) who went so far as to frame the work in the production of an artist identified with the conventional (and somewhat reassuring) name of “master of Rofeno.” It must be said, however, that, with great consistency, Rowley had also referred to this hypothetical “master of Rofeno” the four saints of the fragmentary Sienese polyptych quoted earlier: for that matter, the comparison of the face of the Madonna of Rofeno with that of the Magdalene of the Opera del Duomo is very timely.

But there are also other details that by now have led critics to agree almost unanimously on a Lorenzettian autography. The example of another Madonna and Child, the one from the triptych in the church of San Procolo now in the Uffizi Gallery, is worth mentioning: it is completely comparable (so, rightly, claimed Miklos Boskovits in what would be the last essay written before his death, which occurred on December 20, 2011) to the Madonna that stands out in the cusp of the triptych in Badia a Rofeno. A circumstance that would, moreover, allow the painting to be dated to a period not far from that 1332 to which the Florentine triptych, which the painter signed and dated, dates back (although there are also those who argue for moving it further back in time, given the similarities with the Massa Marittima Maestà ). Boskovits wrote: “The two young mothers with sharp faces and almond-shaped eyes look like twin sisters, and very similar are also the two plump children engaged in playing-or so it seems-with their mother.” That particular gesture of the Child pulling his mother’s veil as a joke is actually, for Boskovits, a foreshadowing of the moment when Christ, “before he is crucified, will be stripped of his garments and then, according to the legend, it will be Mary’s turn to remove the veil from her head and cover her son’s nakedness.”

|

| Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Triptych of Badia a Rofeno, side panels: left, St. John the Evangelist (above) and St. Bartholomew (below); right, St. Ludwig of Toulouse (above) and St. Benedict (below) |

|

| Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Triptych of Badia a Rofeno, Cusp with Madonna and Child |

|

| Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Four compartments of polyptych: St. Catherine of Alexandria, St. Benedict, St. Francis, St. Mary Magdalene (c. 1335; tempera on panel; Siena, Museo dell’Opera del Duomo). Credit |

|

| Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Triptych of Saint Proculus (1332; 171 x 143 cm; Florence, Uffizi) |

One could then continue with the painting’s extraordinary iconographic inventions, peculiar to a painter of such great talent as few could be, and Ambrogio Lorenzetti, an innovative artist and continuous experimenter, was among those who were able to invent new solutions all the time. Of the Madonna in the cusp and its uniqueness in the context of Sienese painting we have already said, but there is more. The Saint Michael in the central compartment is animated by a tension that has no previous counterpart: other artists (Boskovits mentioned Buffalmacco and Bernardo Daddi again), in depicting the archangel Michael, had kept to figures of more solid and calm monumentality, with the devil already largely defeated, or at most about to be overwhelmed. This was not a new theme: new was the way it was approached. The struggle, here, is in full swing: Satan is still well and dangerously active and, as the Hungarian art historian noted, St. Michael does not underestimate him and “gathers all his strength to strike the monster,” with a snap that in similar depictions is unprecedented. And even a later Saint Michael by Ambrogio Lorenzetti, the one made for the hermitage of Lecceto, in the province of Siena, holds a more elegant and composed pose and fights with confidence and precision, rather than strength and energy. For Boskovits, the depiction of the Badia a Rofeno triptych thus had a definite meaning, which also passed through the depiction of the demon as a seven-headed dragon.

An image, the latter, taken from chapter 12 of theApocalypse of St. John: “Then there appeared another sign in the sky: a huge red dragon, with seven heads and ten horns and on its heads seven diadems; its tail dragged down a third of the stars of heaven and hurled them down to the earth. The dragon stood before the woman who was about to give birth to devour the newborn child. She gave birth to a male child, destined to rule all nations with an iron scepter, and the child was immediately raptured to God and to his throne.” A little later,Revelation recounts the battle between St. Michael and the dragon: “A war then broke out in heaven: Michael and his angels fought against the dragon. The dragon fought together with his angels, but they did not prevail and there was no place for them in heaven. The great dragon, the ancient serpent, the one whom we call the devil and Satan and who seduces the whole earth, was precipitated to the earth, and with him his angels were also precipitated.” There are at least two points that the painting has in common with the biblical text: the seven heads and the tail dragging “a third of the stars of heaven” (we see heaven depicted in the turn that the monster’s tail makes). So there is no doubt that Ambrogio Lorenzetti wanted to refer with certain precision to the words ofRevelation. But for what reason? Again Boskovits tries to formulate a hypothesis, which wants the painting as a request for help to the divine spheres against an impending danger. What it was, it is not known: but it is likely that the allusion is to a complicated “political or politico-ecclesiastical situation” whose references, at the time, could be grasped by a rather wide audience.

|

| Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Badia a Rofeno Triptych, detail of Saint Michael fighting the devil |

|

| Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Triptych of Badia a Rofeno, face of saint Michael |

|

| Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Triptych of Badia a Rofeno, detail of the seven-headed dragon |

|

| Left: Buffalmacco, Saint Michael (c. 1320-1330; tempera on panel, 203 x 75 cm; Arezzo, Museo Nazionale d’Arte Medievale e Moderna). Credit. Right: Bernardo Daddi, Saint Michael (c. 1320-1348; tempera on panel, 210 x 110 cm; Crespina, San Michele) |

An audience that certainly did not have to be limited to that of the monks of Rofeno Abbey. A further problem, then, is to understand where the work came from: and given also that the “faux Saint Jacopo” mentioned above constituted a sort of later addition, the Rofeno Abbey could not have been the original home of Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s triptych. Unraveling the puzzle has been tried by Cecilia Alessi in the volume on the triptych published, after the restoration, by Edifir. There is, meanwhile, a sentence in Giorgio Vasari ’s Lives that provides an initial indication: “Ambruogio, finally, in the last of his life did with much of his praise a panel in Monte Oliveto di Chiusuri.” That the work was commissioned by Olivetan monks is now established, given the fact that St. Michael is one of the patron saints of the monastery of Monte Oliveto Maggiore, near the hamlet of Chiusure in Asciano. The same patronage is then linked to the figure of St. Benedict, due to the fact that the congregation of Olivetan monks is part of theOrder of St. Benedict, and follows the Umbrian saint’s rule. Moreover, the Olivetans settled in the Abbey of Rofeno only in 1375: a detail that definitively rules out the place that gives the painting its name as its original location. The triptych in Badia a Rofeno is a work, Cecilia Alessi points out, “painted with a profusion of metals” and “equipped with an important and precious frame”: it is therefore likely that the monks were not the only users and that the work was intended for a church frequented by the population and which at the same time had relations with the Olivetan monks. A likely candidate is the church of San Michele in Chiusure. There are also those, however, who consider plausible a provenance from the abbey of Monte Oliveto Maggiore itself.

A final notation concerns the form of the painting: in fact, the work was cut out in the 16th century to adapt it to the taste of the time, and it is certain that some parts of the original polyptych were lost during the operation (the predella, first of all). The restoration has allowed the rediscovery of parts of the original 14th-century frame, green and with geometric decorations, which is found in a triptych by Ambrogio’s brother Pietro Lorenzetti, preserved in the Lower Basilica of St. Francis in Assisi. The format Ambrogio Lorenzetti used for his triptych was quite recent: a large central panel, wider than the traditional ones, with a scene and no longer with the image of a saint, and flanked by two side panels. It is a typically Sienese format, and in the same period we find it in Simone Martini’s celebrated Annunciation.

To allow the public an easier reading of the work (and its rediscovered frame), it was decided to exhibit it at the Museo Civico di Palazzo Corboli in Asciano separate from the 16th-century woodwork. The public entering the room that houses the Badia a Rofeno triptych will therefore see the painting on one side, and the frame on the other. These are the only two works on display in the room-a particularly appropriate choice to give value to one of the most important, most fascinating, and most problematic works of fourteenth-century art.

Reference bibliography

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.