All the history of Piazza Navona, the most Roman of Rome's squares

On the occasion of the redevelopment of the Crypt of the Church of Sant’Agnese in Agone with the new artistic and architectural lighting system donated by Webuild Group, we discover the history of Piazza Navona, from antiquity to the present.

“Every time you enter the square you find yourself in the midst of a dialogue.” So wrote Italo Calvino in his famous masterpiece The Invisible Cities and, perhaps, such an expression encapsulates better than any other metaphor or description the multifaceted and changing aspects intrinsic to these neuralgic city places. A true locus amoenus for that social animal, which is the human being, who, in the centrality of the square, finds a beating heart of activities, relationships and encounters that have their origin in the much older tradition of the Greekagora . Since the eighth century B.C., in fact, the pólis were born and structured precisely around the square, a pivotal point, along with the acropolis, in the life of every citizen: a place where everyone, regardless of their role and social rank, gathered to weave relationships, knowledge and actively participate in the social life of the city.

A place of encounters, then, where dialogue becomes precisely the undisputed protagonist in the telling of those stories that, inevitably, animate “square life”: stories that, as in the case of Piazza Navona, become essential to the understanding of our everyday life. Among the, perhaps, most fascinating places in the world, Piazza Navona today is animated by a chaotic liveliness that, punctuated by palaces, fountains, obelisks and churches, makes this space truly unique and inimitable, almost timeless. In fact, time has passed since its original “founding” dating back to 85-86 AD. By then in the twilight of the Flavian dynasty, in fact, the then Emperor Domitian, fascinated by the culture of ancient Greek sports practices, athletics above all, decided to build a stadium named after him. The fascination exerted by Greek agonies on the figure of the emperor is further evidenced by the desire to inaugurate the Domitian Stadium on the occasion of the first Certamen Capitolino Iovi, a gymnastic competition held every four years, established precisely in 86 AD.

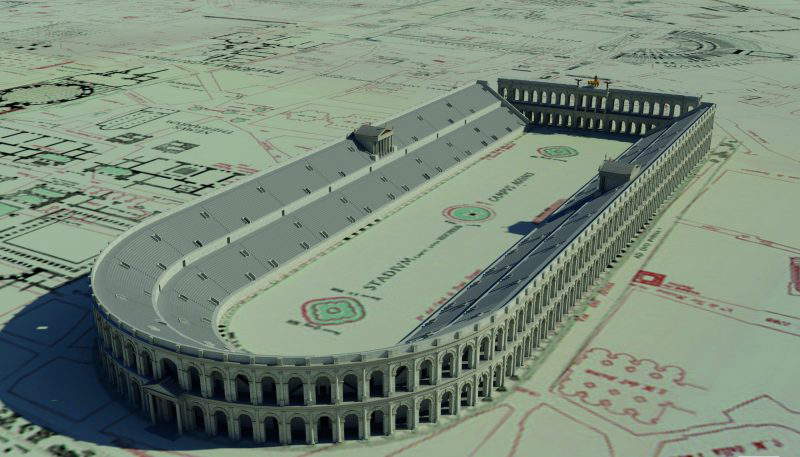

In addition to being considered the first sports complex erected in masonry outside of Greece, the “infrastructure” enjoyed dimensions that were by no means small: 276 meters long and 106 meters wide, it had an arena measuring 193 by 54 meters and, an aspect of no small importance, it was capable of accommodating about 30,000 spectators, not an insignificant capacity for the time. Its floor plan, with its elongated rectangular shape endowed with a hemicycle and a rectilinear end, is today intuitable through a simple perimeter observation conducted from inside the square, but it is even more evident and comprehensible through an aerial view. And it is thanks to the latter “point of view,” observable today by “simply” exploiting the resources offered by the digital world, that it is possible to implement a comparison precisely with the stadiums of ancient Greece and, even more pointedly, with the Panathinaiko Stadium, known to most as the Stadium of Athens.

Although encompassed by later constructions, the original facies of today’s Piazza Navona appears well-defined and fully comparable with the Athenian stadium which, with its final capacity of about 50,000 spectators, can be considered, like the Stadium of Olympia, an absolute reference model in Domitian’s choice. The structure of Domitian’s stadium, made of brick covered with molded and colored stucco, was also intended to be ornamented with marble statues, just like the other large “sports” and non-sports complexes of the time: testimony to this decoration today remains the well-known statue of Pasquino. Placed at the corner of Palazzo Braschi, the famous “talking” statue (which, not coincidentally, gives its name to the square of the same name adjoining precisely Piazza Navona) was found in 1501 during excavations for the road paving and renovation of the then Palazzo Orsini, now Palazzo Braschi. The statue, though extensively damaged and mutilated in its limbs, has Hellenistic features, evident in the torsion of the bust, attributable to the distant 3rd century BC. Of considerable interest, moreover, appears to be observing the pseudo-armor encircling the bust of Pasquino as well as speculating how the marble block placed at his “feet” may, in fact, be interpreted as an additional figure depicted from behind and intent on fighting with the very main subject. The group, therefore, could depict a fight scene, a competition not surprisingly practiced precisely in the agons of ancient Greece. In spite of an objective difficulty in the correct iconographic reading of the statue, resulting from the mutilated condition in which it lies, the marble group nevertheless is also interpreted by critics with the figure of Menelaus intent on supporting the dying body of Patroclus. Such a key interpretation, by virtue also of the detailed narration in theIliad of the funeral games held in honor of Patroclus’ subsequent departure, is exceedingly fitting especially when compared with the “sporting” site where it was located.

The Domitian Stadium, therefore, continued to maintain its function continuously until 217 CE, the year in which, under the regency of Emperor Macrinus, the complex underwent adaptation work following the fire that occurred at the Colosseum. In the absence, in fact, of the Roman venue “par excellence,” there was a need to host gladiatorial games, and the stadium located in the Campus Martius proved to be the most suitable location for this purpose. Later, it was not until 228 CE, during the time of Alexander Severus, that the stadium underwent restoration work.

With notable and more than plausible certainty, the complex retained its original function until the 8th century when the first church of St. Agnes was built in the first order’s fornixes. The pre-existence on which the much more monumental and baroque church, now known as Sant’Agnese in Agone, arose in fact on the site that tradition identifies as that of the saint’s martyrdom, and this therefore leads one to think that, from the century in question, the Stadium of Domitian must inevitably have begun to lose its original use.

Between the tenth and twelfth centuries the chronicles tell us of a place intended for recreational uses, a use that persisted until the Renaissance period: it is no coincidence that in the second half of the century Pietro Barba, who ascended to the papal throne under the name of Paul II, decided to use the ample spaces of the square to host the Carnival, while his successor, Sixtus IV, on April 25, 1476, St. Mark’s Day, opted to offer the people a jousting which was placed in the center of today’s square. To this was added that in 1477, under the pontificate of Sixtus IV, the area was used as the site of the local market since, precisely at the express papal request, Piazza Navona was identified as the most suitable location to transfer to it the market which, until precisely the Sistine redevelopment, was held on the Capitoline square between the “noble” Palazzo Senatorio and Palazzo dei Conservatori.

With regard, then, to the “reuse” of the stadium, what should be highlighted with extreme attention turns out to be the raising of the floor level of the area: throughout the Middle Ages, in fact, the stadium, going to lose its “importance,” saw its structures begin to be destroyed or used as a “source” for the procurement of bricks to be used in different constructions. The complex, thus, slowly became a kind of quarry within which debris was poured and around which buildings and churches of absolute importance began to be built.

Emblematic evidence of the difference in height that inevitably occurred between the original site and the later development turns out to be, today, what can be observed in Piazza Tor Sanguigna. Located only a few meters from the northern “entrance” of Piazza Navona, Tor Sanguigna preserves a valuable archaeological evidence of a masonry archway of the ancient stadium. This pre-existence, therefore, allows us to confirm the material used for its construction but, above all, it allows us to observe how the original walking surface was about 5 meters different from today’s much “higher” surface.

The Renaissance period, therefore, laid the foundations for the much more substantial and “impactful” urban renewal that was put in place in the first half of the seventeenth century, effectively leading Piazza Navona to become one of the symbols par excellence of Baroque Rome. In the course, in fact, of the great and unique seventeenth-century season, Rome, true caput mundi artistica, underwent a radical change, both urbanistic and architectural, dictated especially by the great patrons of the time, ecclesiastical and secular.

Within this framework, in fact, was the Pamphili family represented, in a very marked and authoritative way, by the figure of Giovanni Battista. Having ascended to the papal throne under the name of Innocent X, the pontiff first arranged for the construction of the “family palace” already present in the square and originally built in 1630 through the union of different properties owned by the family. The pontiff, elected in 1644 and eternalized by the famous brush of Diego Velázquez, decided to ennoble the palace by giving it even more monumental forms. The work was entrusted to the renowned architect Girolamo Rinaldi, appointed prince of the Academy of San Luca in 1641, who devised the extraordinary facies with which Palazzo Pamphili, now the seat of the Brazilian embassy, faces the square: three interior gardens, twenty-three rooms on the piano nobile, and the precious Gallery designed by Borromini and frescoed by Pietro da Cortona.

Consequently, the same performers, with the fundamental addition of Francesco Borromini, starting in 1651 renovated the church of Sant’Agnese in Agone in Baroque forms. The church, also initially commissioned to Rainaldi, following the intervention of Innocent’s influential sister-in-law Olimpia Maidalchini, was entrusted to Francesco Borromini. The Ticinese architect intervened in part on the original project by going, in particular, to modify the facade, which with its concave and convex forms (typical of Borromini’s language) would thus place the dome in greater prominence.

Also due to the capital figure of Innocent X is perhaps one of the most iconic sculptures of the entire Roman and national scene, which today adorns the entire Piazza Navona with its beauty: the Fountain of the Four Rivers. Commissioned in 1648 by none other than Gian Lorenzo Bernini, the fountain, the largest of all those in the square, turns out to be the outcome of the work of some of the most influential Roman sculptors of the seventeenth century. Made to convey the waters coming from the “Acqua Virdis” aqueduct, the fountain is animated by allegories of the four main rivers present in the various continents: the Nile, the work of Giacomo Antonio Fanelli, the Ganges by Claude Poussin, the Danube the result of the chisel of Antonio Raggi, and the Rio de la Plata made by Francesco Baratta. In the center of the fountain Innocent X decided to place theAgonal Obelisk, which, by now in ruins, he had disassembled and arrived in four large “rocchi” directly from the Circus of Maxentius along the Appian Way. Bernini’s fountain, therefore, further enriched a square in which the two 16th-century fountains commissioned by Gregory XIII from Giacomo della Porta were already present: the Fountain of the Moor and the Fountain of Neptune, the latter with baroque, yes 16th-century, but with statues of later 19th-century workmanship.

The great decorative architectural renewal of the square, thus begun by the Pamphili family, came to be completed in the following centuries with a further late 18th-century climax: the construction of Palazzo Braschi. Located between Piazza Navona and Corso Vittorio Emanuele, the building was designed by the architect Cosimo Morelli on commission from the then Pius VI; the pontiff, in fact, wishing to pay homage to his own nephew, Luigi Braschi Onesti, with a tangible testament to family power, decided to have him build the palace in question, the basis of which was still those nepotistic principles that, a few years later, would find an end with the ferments of the French Revolution. In 1791, therefore, the 15th-century Palazzo Orsini was demolished and, on the same plot of land, the palace that has housed the Museum of Rome since 1952 was built.

The

The The Fountain of the

The Fountain of the

Continuing in history, the following century, the nineteenth century, stands out as the time in which Pope Pius IX, the longest-serving pontiff to assume the Petrine throne, decided in 1866 to permanently abolish the well-known “flooding” of the square. Since the 10th century, as pointed out, the square had become the scene of playful events. In addition to this aspect, from 1652 the aforementioned Innocent X decided, in the hottest months, to block the drains of the fountains to create a kind of artificial lake whose purpose would be to provide refreshment to the population during the hottest periods. This procedure, before it was abolished, was skillfully documented both through valuable artistic evidence, as is clearly evident in the famous painting Water Games in Piazza Navona by Giovanni Paolo Panini (now preserved at the Landesmuseum in Hanover), and through valuable photographic shots from the second half of the 19th century.

The nineteenth century, then, gives way to the twentieth century with a square that, having lost its ancient agonal value and simultaneously its more “playful” vein, did not go through further changes also due, unfortunately, to the two world wars that would mark the first half of the twentieth century. On the other hand, however, fortunately Piazza Navona passed “unscathed” through the first forty-five years of the twentieth century, only to face a post-war period that would guarantee it a decidedly “undignified” fate.

The economic boom that characterized, in fact, Italy at the turn of the fifties and sixties, marked a high and sudden industrial growth that led to a substantial increase in population as well as a consequent “overcrowding” of certain goods that were indispensable for every Italian family: among them, the automobile. Hence, Piazza Navona became, against all present-day logic, an open-air artistic parking lot, “Bernini&Borromini” view, completely distant from its previous “functions.”

Between the 1960s and 1970s the continuous industrial development prompted concrete reflections on the condition of some Italian cities, and consequently of their precious “historic centers,” now asphyxiated and conditioned by urban traffic. Thus it was that in 1968 Piazza Navona became Italy’s first “pedestrian island,” thus going on to pave a road that would lead, in the following years, to the pedestrianization of further iconic artistic places such as Piazza Maggiore in Bologna or Via dei Calzaiuoli in Florence.

Piazza Navona (originally Piazza “in Agone,” from the Latin agon meaning “game”) can, therefore, be considered one of the most unique, significant and at the same time complex artistic-architectural complexes in the entire historical, architectural and cultural landscape of Italy: a place where the charm of the ancient, combined with the magnificent and illustrious seventeenth-century artistic testimonies, allow us to fully enter that paradoxically timeless Calvinian dialogue.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.