“I like concept design, that which is so clear that you may not even draw it. Many of my designs I have conveyed over the phone.” If it is true that “good design lasts a hundred years,” Vico Magistretti’s Nathalie bed , in production since 1978, can undoubtedly already be considered an example of good design. The opening words are from Magistretti himself, a Milan-born architect and designer who is considered one of the fathers of Italian design.

Born in Milan in 1920, the son and grandson of architects, Vico Magistretti began his work in his own family’s studio, in a Milan that was in growing ferment and expanding in the immediate postwar period. During this period he came into contact with those exponents of the Modern Movement-or rather, of Italian rationalism-present in Milan, such as Ignazio Gardella, Franco Albini and others, figures who were fundamental to his education, in whom he found his own enthusiasm for architecture. If the beginning of his career saw him as the protagonist, in collaboration with other architects, of the design of 14 interventions for INA-Casa, of fine buildings in Milan such as the Torre del Parco and the office building on Corso Europa, and of numerous domestic interiors, it was, however, in a Milan of the early 1960s, surrounded by a dense network of high quality craftsmanship that was slowly turning into industrial production, that his encounter with design took place.

Always interested in the theme of the home and the problems of living, since “the place where one lives must be alive, rich in evidence of people’s present and past, it must tell their story,” Magistretti would begin to collaborate assiduously with manufacturers such as Artemide, Cassina, and Gavina, creating objects that reach into the contemporary, remaining “classics” of Italian design. A design that extends to aspects of living tout court and that Magistretti himself considers unique, indeed, almost a miracle. In fact, he argues that “the birth of Italian Design owes a great deal to the close conversation between production and those who design: it was born from producers who wanted to change, grow, evolve. And - also because of this - it has lasted since 1960.” The design he champions is characterized by a factor, that of the very close communication between producer and designer, which has not been repeated elsewhere and finds happy developments in Italy.

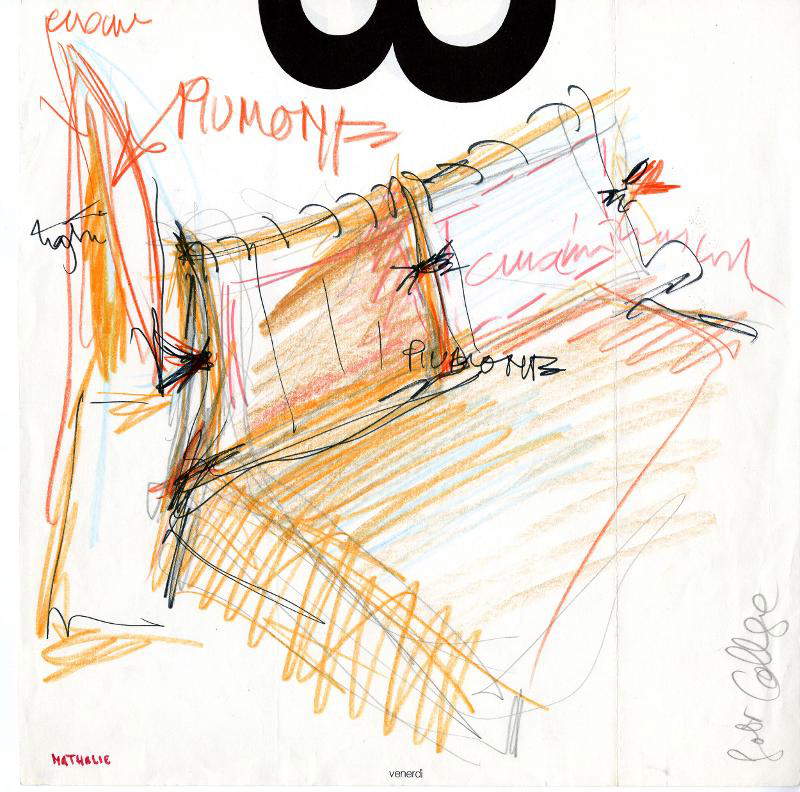

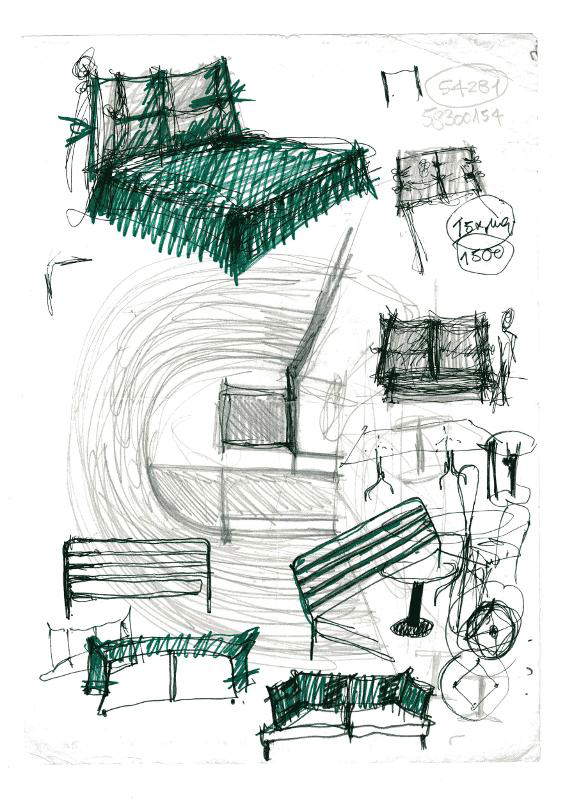

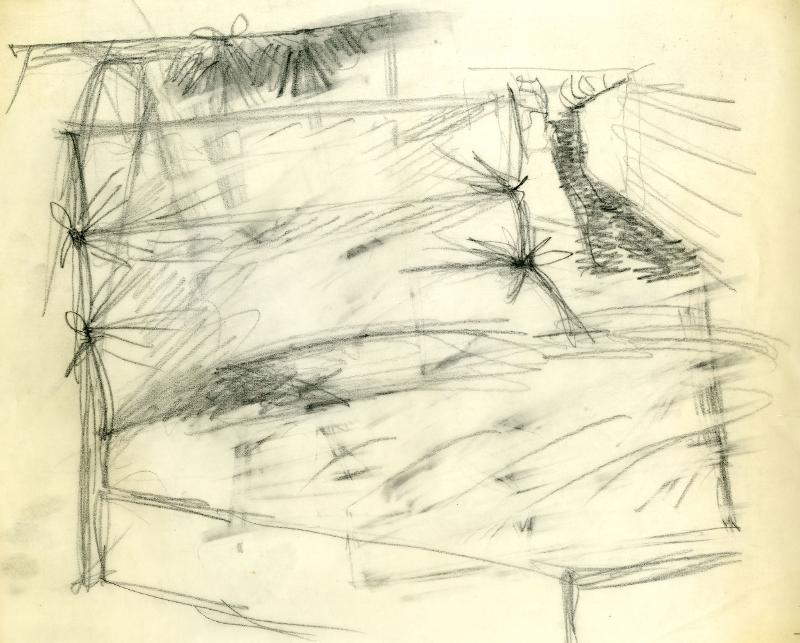

So it is dialogue and collaboration that are the real secrets behind the objects designed by Magistretti. Objects that are always animated by a concept, a fundamental core, an idea that must be simple and transmissible already in words, without the necessary aid of drawing. In this simplicity he locates the soul of his design, in a process dynamic that, as he recounts, sees the designer and the manufacturer linked together already in the definition of the concept, which will then be developed in a second phase. His definition of “projects over the phone,” or ideas born out of direct conversation with those who would later be involved in production, as in the case of the Chimera lamp for Artemide, remains famous.

Magistretti’s design ideas are also marked by the search for innovative technical solutions and a broad way of designing that goes beyond the determinations of individual technological solutions. The design product must therefore be a simple object that has great potential for use and can conceptually say something, suggesting a new use of the material or object itself and representing a “conceptual” design rather than a mere “formalistic design.” A design that, it should be remembered, is developed not so much in the solitude of the studio as outside, through the encounter between designer and manufacturing industry, itself the repository of technical expertise, knowledge of materials and their evolution. It is this encounter that makes it possible to create culture, which for the Master means “being able to distinguish what is most important from what is least important.”

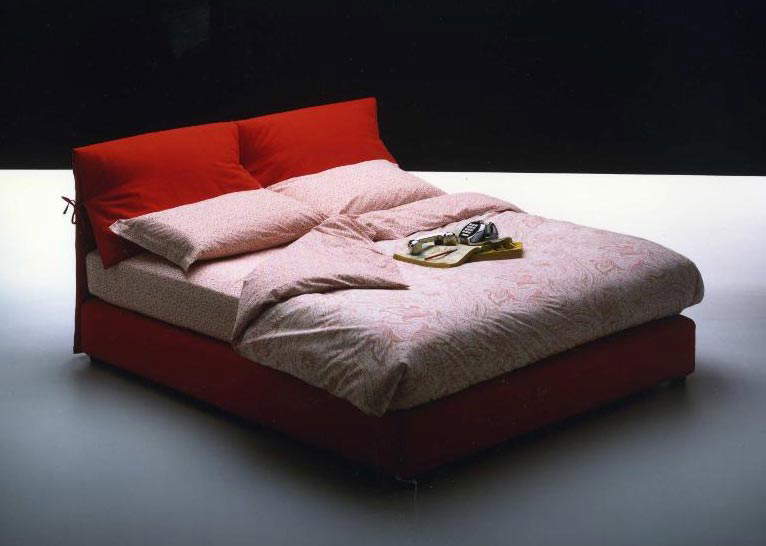

It is precisely from a “suggestion” of the designer that in 1978 the Nathalie bed, produced by the fledgling company Flou, came to life. It is configured as the first prototype of the “textile bed,” a definition that according to the designer himself sums up its meaning fully: “Sometimes the simple word or concept expressed in words generates the form. Textile bed: an almost undesigned form but already determined by the use of the suggested material; very suitable for the ’idea’ of bed, the use of the attribute ’textile’ comes from the extension of the concept of Duvet; the new way of covering the bed, the new way of remaking it and making it more comfortable and cozy.”

Rossano Messina, an enthusiastic co-owner of Flou, immediately grasped its potential. At a time when consumer choices were oriented toward products that were practical, functional, but also in line with one’s taste and personality, Nathalie embodied all this. Indeed, it proposed a unified image, in which the “soft components,” i.e., pillow, pillow cover on the headboard, comforter, mattress, and frame cover, form a single system, and where the comforter “with its soft folds and shadows rises to form the headboard.” A headboard that serves not only as a support, but also to contain and hide, by day, the pillows. It is Magistretti himself who claims that “the secret of Nathalie’s success lies in a basic innovation, later much copied: the use in rigid form of the comforter, which until then had always been exploited only as a blanket while with Nathalie it becomes a soft headboard to lean on.”

In an almost natural way, the idea then developed to change its cover (since it is completely removable) and to study linen coordinates that, by unlocking the traditional rigidity of the bedroom, would offer more freedom in choice, allowing the product to remain the same in form, but at the same time to “change clothes often.”

Nathalie thus lives by the fundamental contribution of fabric, which, however, Magistretti is interested in as such, in order to achieve essential results of comfort, practicality and overall appearance. He almost ignores the problems associated with the “decorative” aspect, so much so that he claims, “in fabrics I look little at color, I look instead for structures, textures, the technical functional aspect....” However, it is undoubtedly also the possibility of being able to play with colors and patterns that contributes to Nathalie’s success. It is important to consider that this success is also the result of a second aspect: the search for a new way of sleeping.

Nathalie in fact becomes the symbol of an attention to the deeper aspect of rest: the bed not only as an object of furniture, but also as an instrument of well-being. Flou thus becomes the spokesperson for a new philosophy, that of sleeping well. Over the years, in fact, the “textile bed” has evolved into a real system with a choice of four bases (rigid, with storage, in aluminum) and three different sleeping surfaces (adjustable slatted, orthopedic with manual or electric movement), adapting to different needs, and confirming the company’s ability to innovate the product by following the needs of the market. This is echoed in Renato Messina’s words, “When we realized that the TV was moving from the living room to the bedroom, we made our Nathalie recliner.”

After almost fifty years, Nathalie continues to be an object intended for consumption but “removed from the logic of consumerism,” as it continues to represent something in which to recognize itself, to be an object that becomes an integral part of the home and its everyday life, in that view of durability, quality and simplicity proper to “good design.” In it, form and function proceed in parallel, the individuality and creativity of the designer dialoguing with the techniques and materials of industry, with the aim of entering not only the market, but also the lives of people, suggesting to them a new way of using reality, which is, according to Magistretti, the true task of Design.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.