by Federico Giannini, Ilaria Baratta , published on 17/10/2019

Categories: Works and artists

/ Disclaimer

Albrecht Dürer's "Rhinoceros" is one of the most famous animals in art history: let's trace its origins and the fortunes of the German artist's celebrated print.

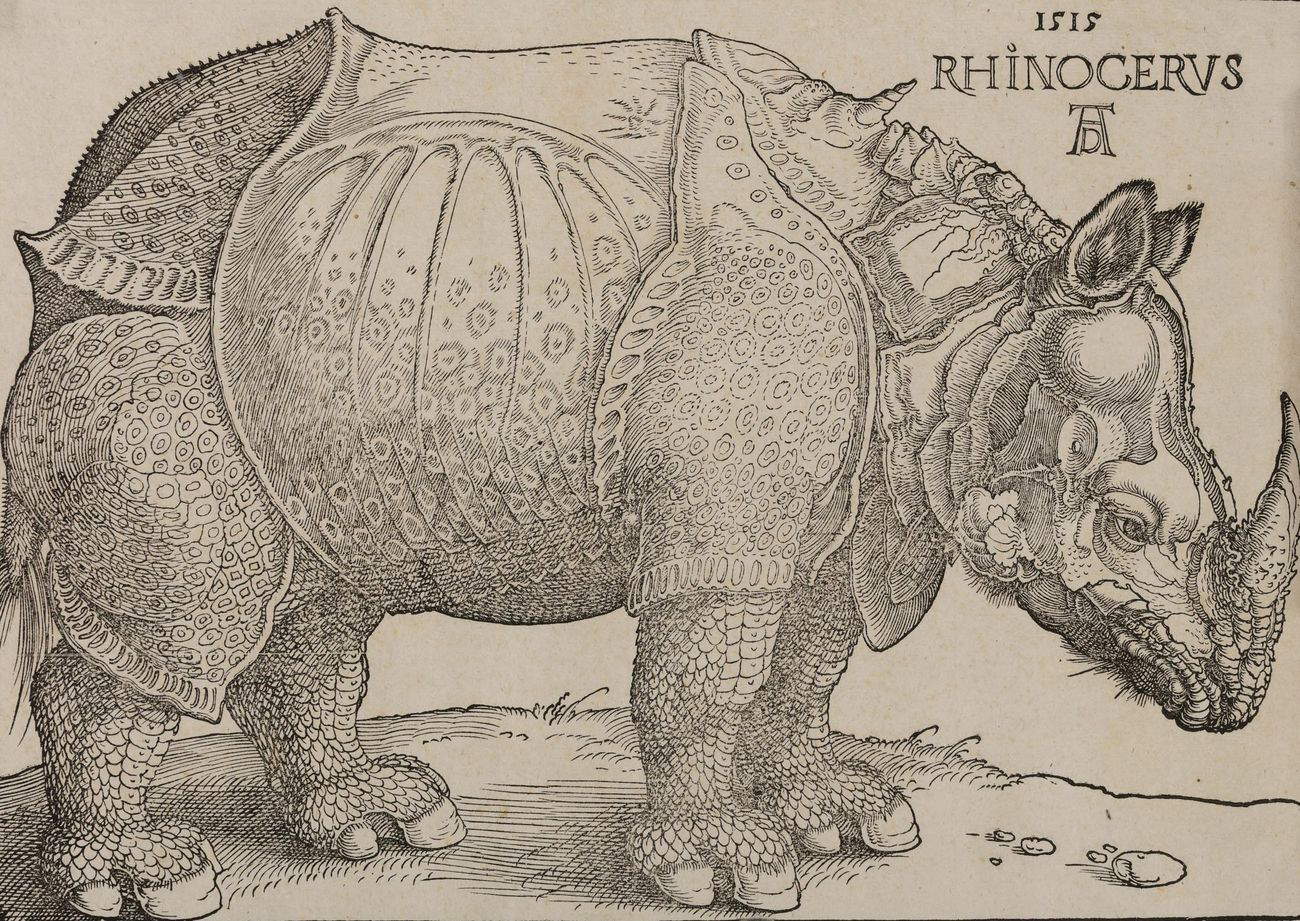

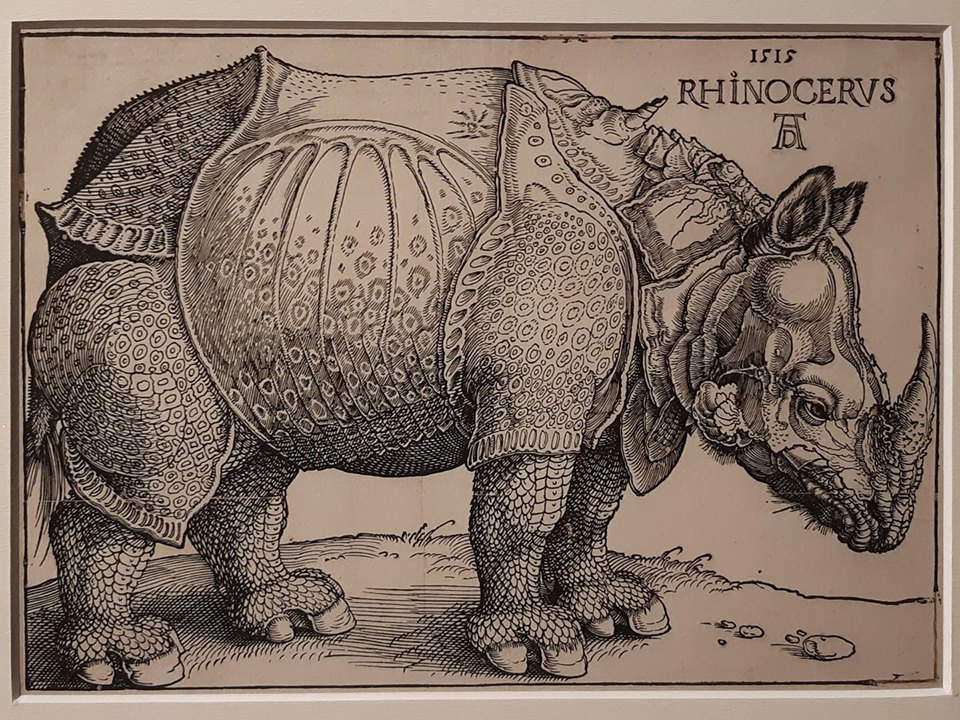

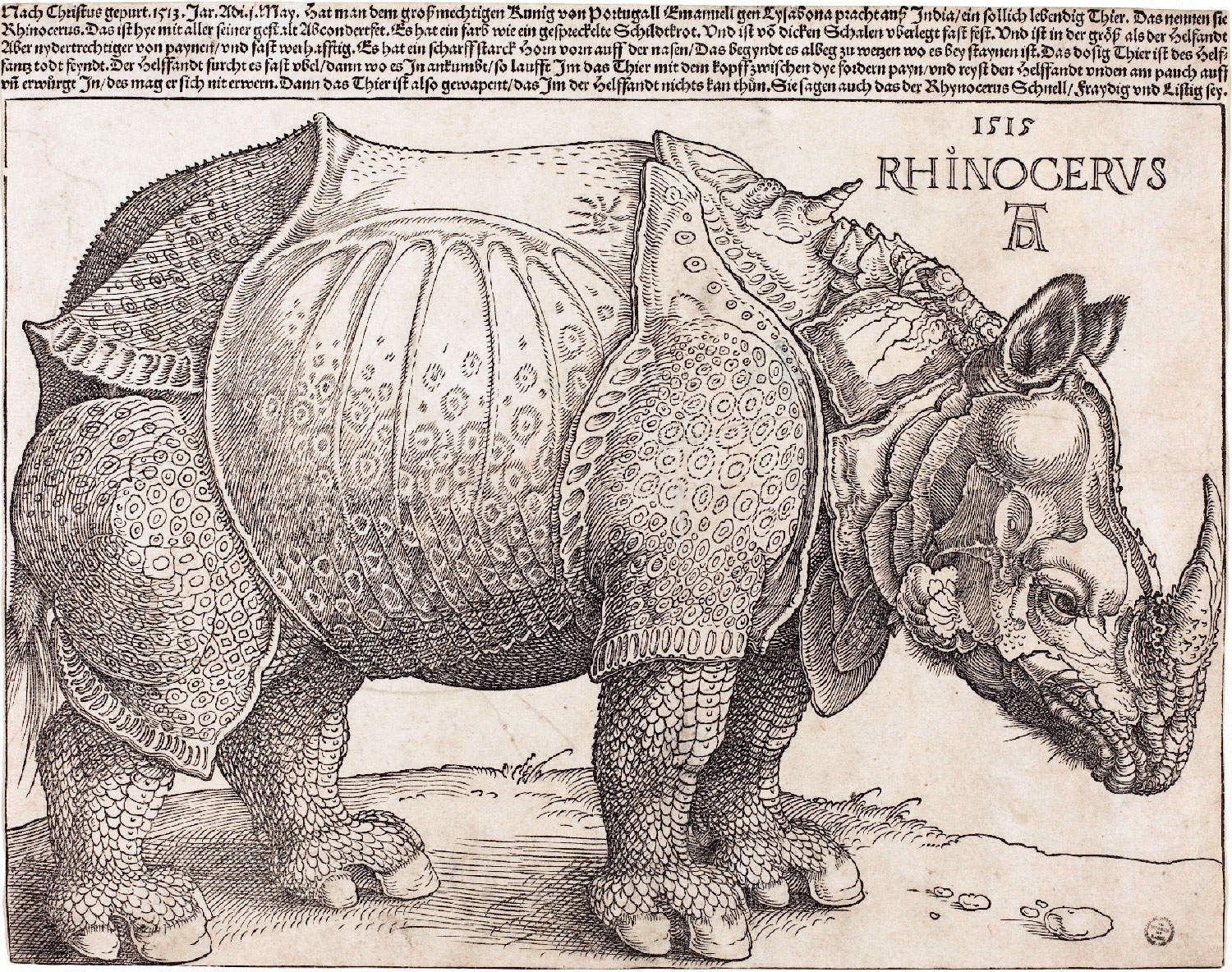

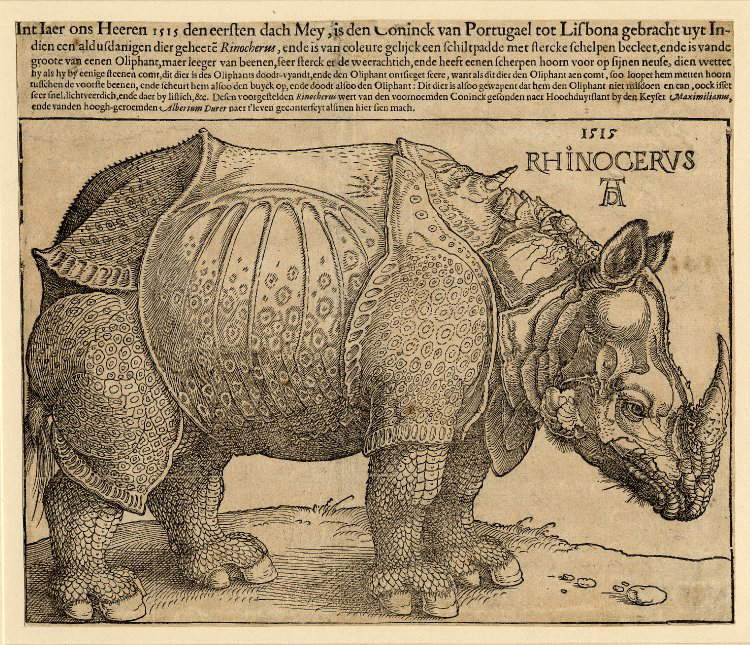

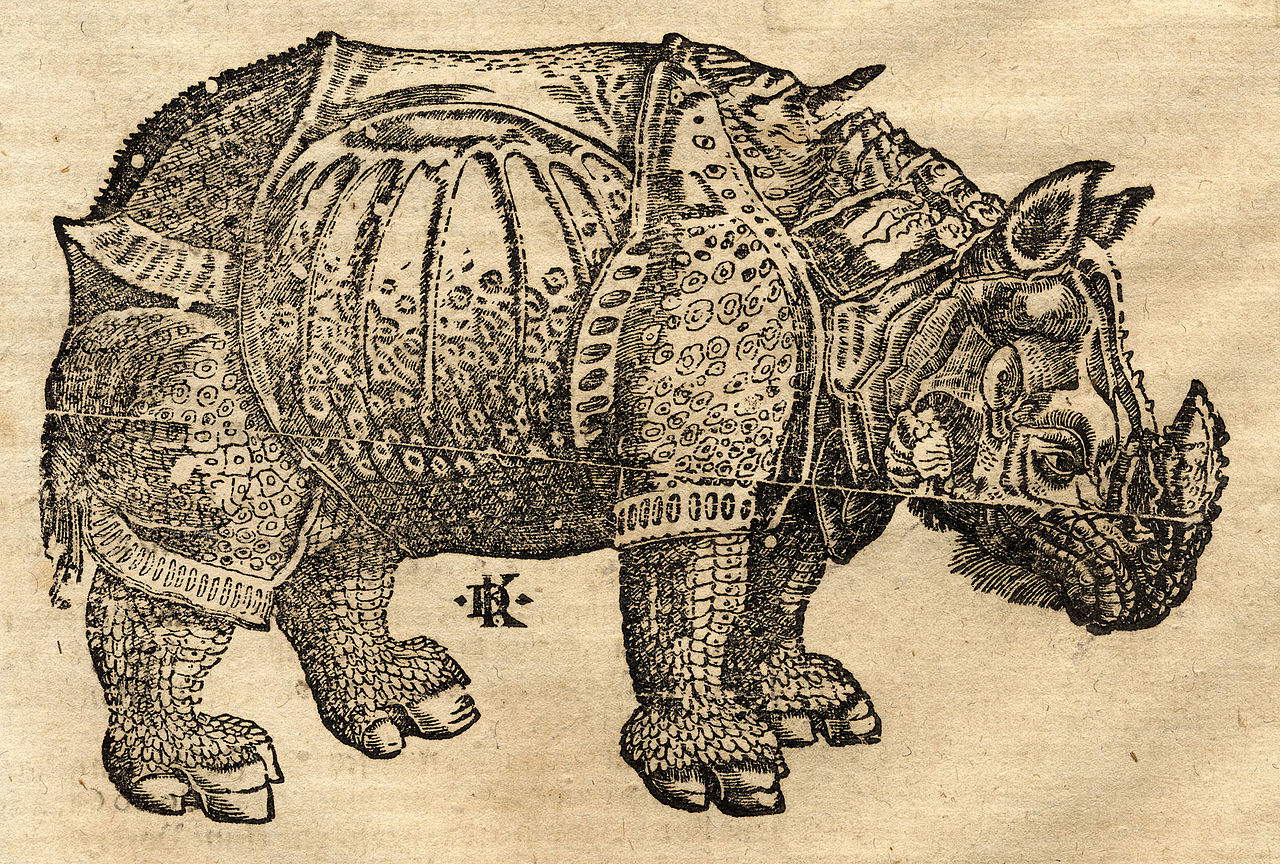

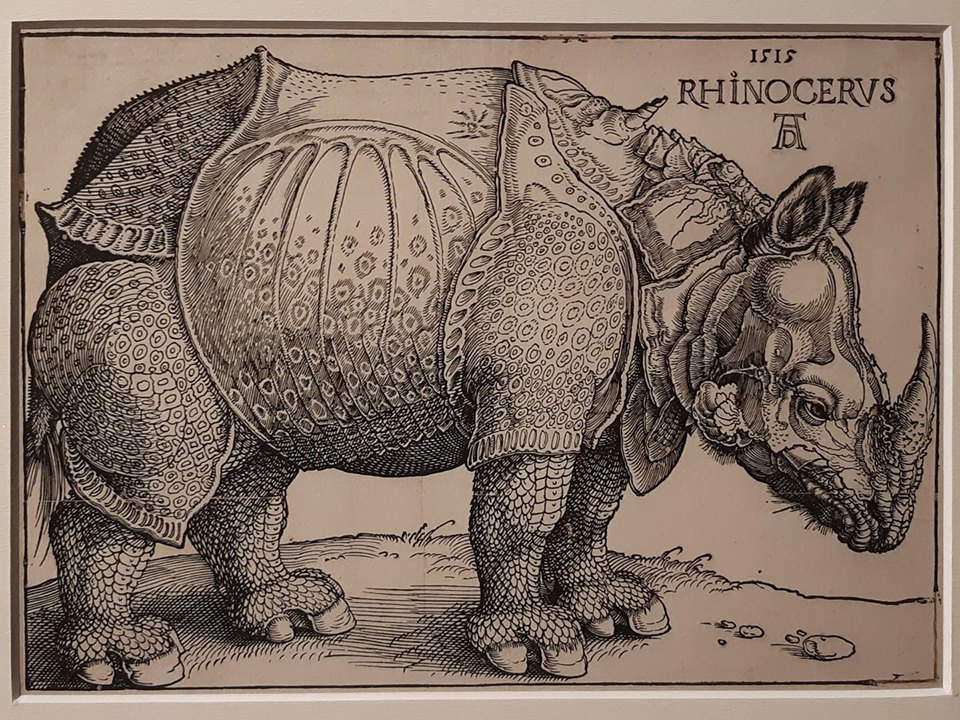

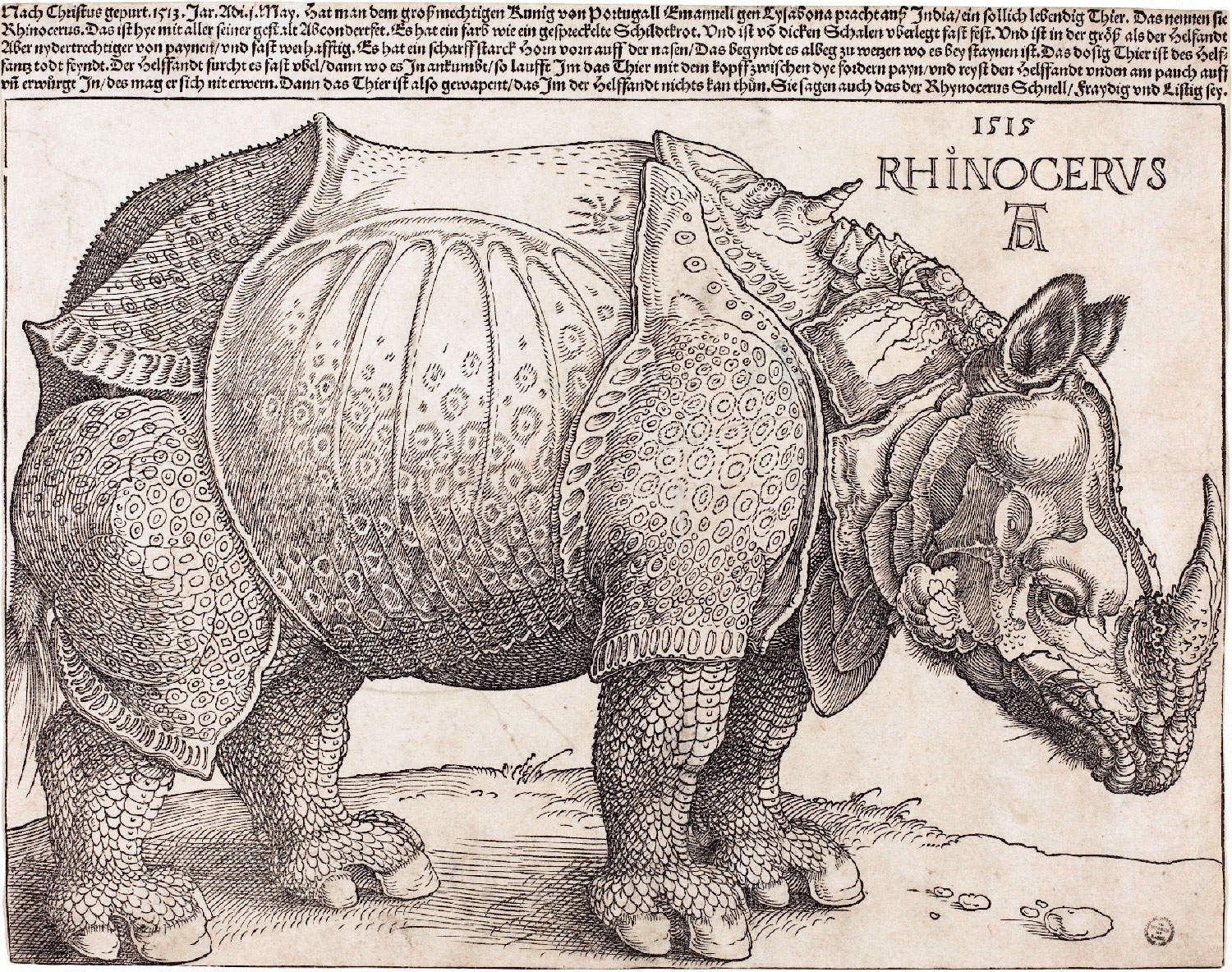

Among the most famous prints of the conspicuous graphic production of Albrecht Dürer (Nuremberg, 1471 - 1528), who as is known was a tireless and extraordinary engraver, the most curious is surely the one depicting a bizarre rhinoceros: specimens of this celebrated woodcut are now preserved in several museums around the world, although they survive in far fewer numbers than those that were pulled in ancient times. In Italy, it can be found, for example, at the Musei Civici in Bassano del Grappa (it is part of the Remondini collection, one of the world’s most comprehensive collections of Dürer engravings), or at the Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe in the Uffizi Gallery, as well as in some private collections, which from time to time lend it for temporary exhibitions. A privately owned specimen, for example, was included in the exhibition Albrecht Dürer. The Privilege of Disquiet (at the Museo Civico delle Cappuccine in Bagnacavallo from Sept. 21, 2019 to Jan. 19, 2020), an exhibition that with one hundred and twenty graphic works by Dürer set out to investigate the many souls of his printed production. Therefore, the Rhinoceros could not be missed, since, among Dürer’s prints, it is one of those that most move the public by surprise: a work with which the artist “affirms his extraordinary curiosity” (so writes Patrizia Foglia, curator of the Bagnacavallo exhibition together with Diego Galizzi), the print depicting the extravagant pachyderm has been the object of the attentions of many art historians, and a great deal has been written about it.

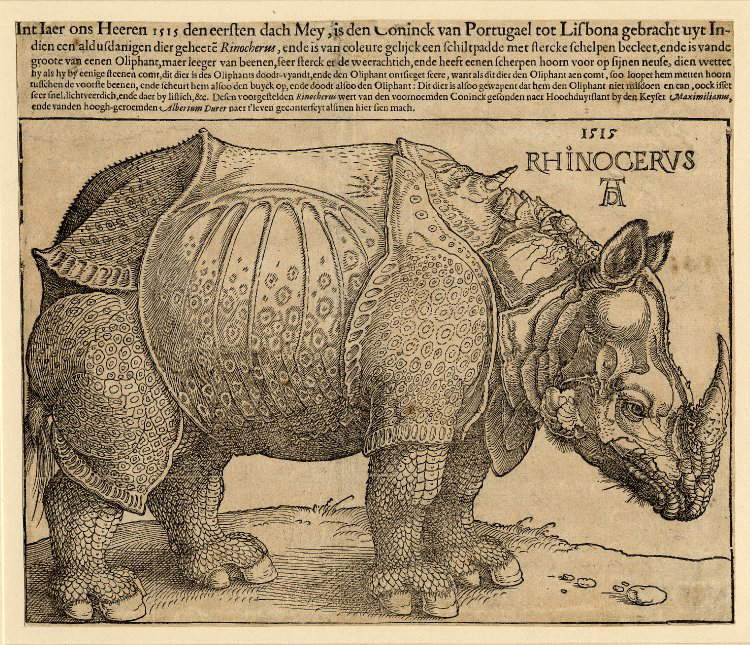

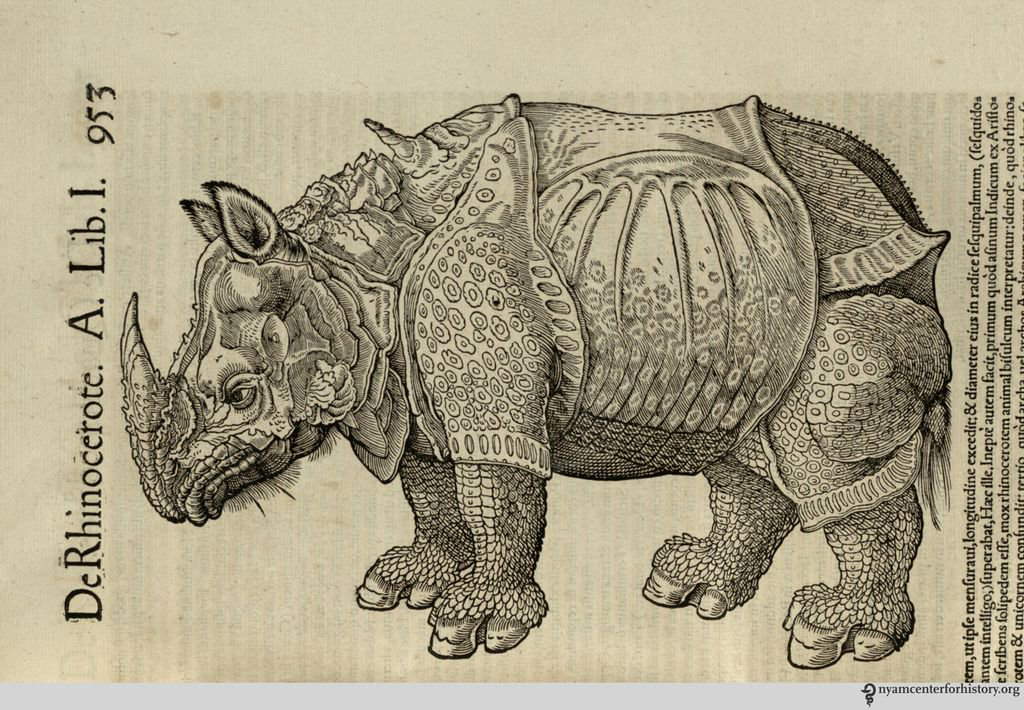

Striking the interests of scholars is, first and foremost, the appearance of the rhinoceros. Firmly planted on its solid paws (which Dürer decorated with reptile-like scales), the animal appears as if covered by an impenetrable layered armor similar to that of a soldier or knight in the early 16th century, decorated with geometric motifs in a circular shape, with a horn on its back, nonexistent in real rhinos, but which the artist included in his depiction anyway. It should be clarified that Dürer’s is an Indian rhinoceros, a species whose scientific name is Rhinoceros unicornis, because of the peculiarity that, compared to African rhinos such as the black rhinoceros(Diceros bicornis) or the more famous white rhinoceros(Ceratotherium simum), it has only one horn on its snout, as opposed to the two horns of the African species. Another very obvious feature that separates the Indian rhinoceros from African rhinos is the shape of its skin: in fact, the Indian rhinoceros appears to be covered with a thick armor that in some areas (at shoulder height, in the middle of the back, on the legs) forms large folds that make the beast look as if, indeed, protected by armor. The numerous outgrowths that develop on the epidermis of the Indian rhinoceros are what Dürer depicts in the form of ornament-like circles.

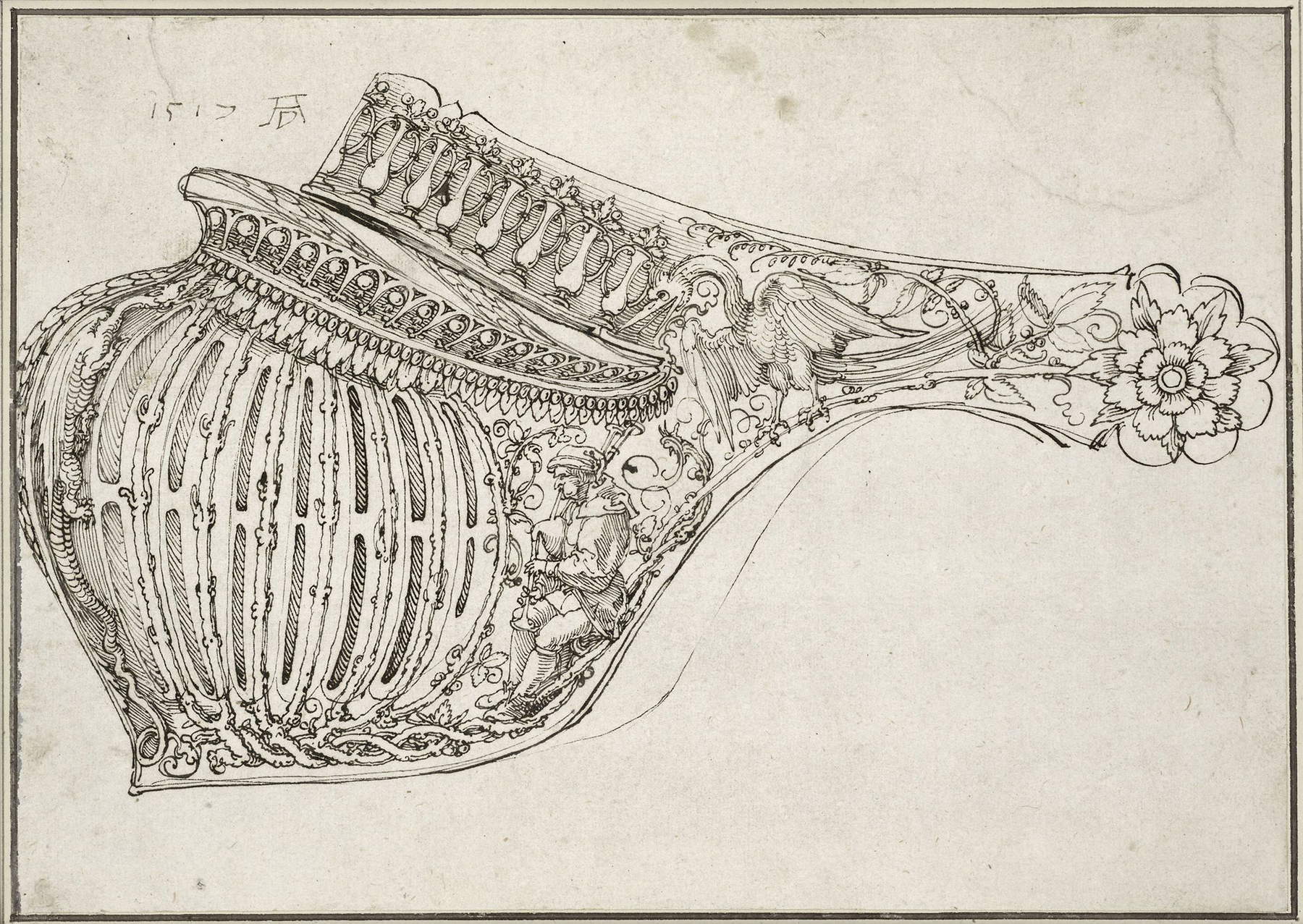

It was precisely on the fair aspect that gallery owner Harry Salamon, who edited one of the first Italian catalogs of Dürer’s engravings, focused in 1969. “Since he could not habitually depict an animal except from a veristic point of view,” the dealer wrote, “it was natural for him always to make use of the burin, given the abstract, expressionistic and concise nature of the stylographic technique that he himself had created. All the more significant, therefore, is the choice of this medium to describe the forms of the extraordinary animal that is the rhinoceros. It would, of course, be absurd to speak of an insight into that way of thinking about the poor animal peculiar to so much modern literature, whereas the interpretation in a surrealistic key given to us by Dürer clearly arose as pure amusement at the incredible appearance of the beast and its mighty armor.” And equally interested in the appearance of the armor was art historian Tim H. Clarke, author, in 1986, of an essay entirely devoted to the Nuremberg artist’s Rhinoceros, in which he drew an interesting parallel between the animal and the armor Dürer could easily see: “we know,” Clarke wrote, “that Dürer shared with many of his contemporaries a fascination with the exotic; and we also know of his close relationship with the Nuremberg armorers. These two facts are a sufficient answer to why the artist made his woodcuts. Regarding exoticism, Dürer wrote in his notebook, after a trip to Holland in 1520-1521 where he first saw a group of Mexican works of art, that ’they are more beautiful to behold than any other wonder.’ But the connection with the gunsmiths is what makes the engraving so exceptional. Dürer lived on the street near the gunsmiths’ district, the Schmiedegasse, and was actively engaged in drawing weapons.” Clarke, moreover, also saw a similarity between the ribs of the Rhinoceros and the decorations that appear in the drawing for a tournament helmet visor that Dürer made in 1517. And even a great scholar such as Ernst Gombrich was fascinated by the appearance of Dürer’s Rhinoceros: “When Dürer published his famous engraving of the Rhinoceros,” Gombrich wrote, “he had to rely on second-hand accounts, which the artist supplemented with his imagination, coloring them, no doubt, with what he had learned from the most famous of exotic beasts, the dragon with its armored body. And it has been shown that this creature, half practically invented, served as a model for all illustrations of rhinos, even in natural history books, until the seventeenth century.”

|

| Albrecht Dürer, Rhinoceros (1515; woodcut, 215 x 230 mm; Bassano del Grappa, Musei Civici) |

|

| Albrecht Dürer, Rhinoceros (1515; woodcut, 212 x 298 mm engraved, 221 x 306 mm sheet; eighth edition specimen, 17th-century print run; Private collection) |

|

| Albrecht Dürer, Rhinoceros (1515; woodcut, 235 x 298 mm; Washington, National Gallery of Art) |

|

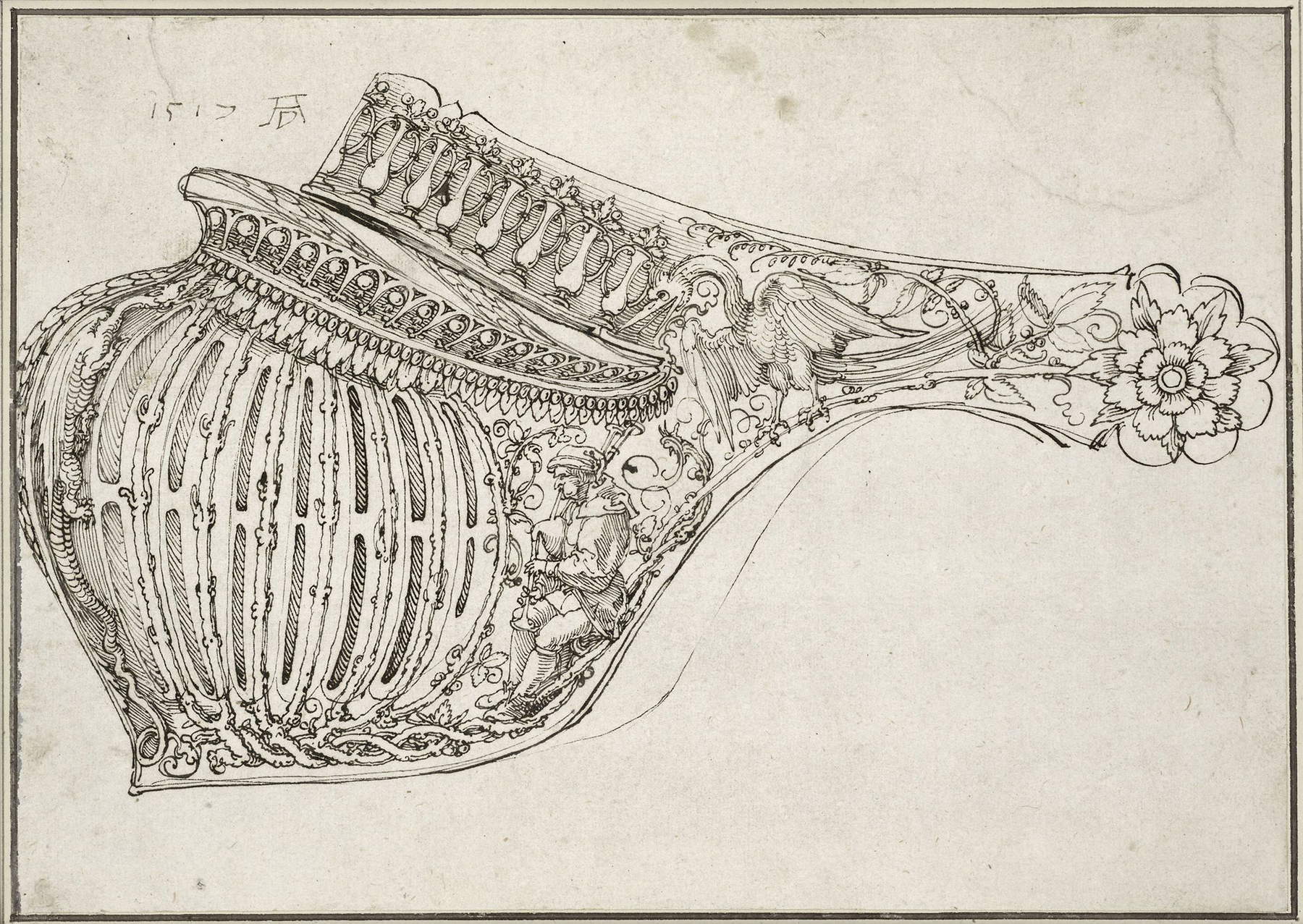

| Albrecht Dürer, Visor for Tournament Helmet (1517; pen and brown ink on paper, 194 x 276 mm; New York, Metropolitan Museum) |

|

| Indian Rhinoceros. Ph. Credit Darren Swim |

|

| White rhinoceros. Ph. Credit Rob Hooft |

Scrolling through the texts just reported, it becomes clear that Dürer, in drawing his rhinoceros, had to work a lot withimagination andfantasy. Indeed, many who see the German artist’s woodcut ask the question: where was it that Dürer had seen a rhinoceros? Were there similar animals in early 16th-century Nuremberg? The answer is no: the artist had never seen an Indian rhinoceros in his life, nor would he ever get to see one live. As Gombrich points out, the artist based his work on accounts from those who had seen the rhinoceros instead. So, somewhere in the Europe of those years, a rhinoceros had arrived from India. To trace the story in broad strokes (and to get an idea of the astonishment that the animal aroused upon its arrival, at a time when no one had ever seen one live, since the last rhinoceros had arrived on our continent in Roman times) one can start from theinscription that appears, by way of commentary, in some print runs of the Rhinoceros (given here in the translation from the Dutch, which appears, for example, in the British Museum specimen, published in Albrecht Dürer: Originals, Copies, Derivations edited by Giovanni Fara): “In the year of our Lord 1515, on the first of May, there was brought from India to the king of Portugal at Lisbon a living animal called Rhinoceros, of the yellow color of a tortoise-shell, covered with stout scales, of the same size as an elephant, but shorter on the legs, very strong and almost invulnerable, and with a sharp horn on its nose, which it sharpens over stones. This animal is the deadly enemy of the elephant: the elephant is very frightened of it, for when this animal meets it, it charges it with its head down against its front legs, and wounds its stomach and finally kills it. This animal has such powerful armor, that the elephant can do nothing against it; it is also said to be very fast, lively and cunning.”

The story told in the inscription is a little imprecise, but the substance does not change: on May 20, 1515, a ship from India landed in Lisbon and, in its cargo, carried an Indian rhinoceros that the sultan of the Indian state of Gujarat, Muzaffar II (? - Ahmedabad, 1526), had given to Alfonso de Albuquerque (Alhandra, 1453 Goa, 1515), a famous explorer, conquistador and governor of Portuguese India from 1509 to 1515. Alfonso de Albuquerque sent the gift to King Manuel I of Portugal (Alcochete, 1469 Lisbon, 1521), embarking the beast on the Nossa Senhora da Ajuda, a vessel that sailed from Goa towards the Portuguese capital. Poor Ulysses (this is the name Portuguese sailors would have given the rhinoceros: and indeed his peregrinations by sea were many), having just arrived in Portugal after a four-month voyage across the ocean, immediately became something of a freak, an attraction to amuse the king’s guests and others. Sources attest that, in order to confirm the veracity of the belief that rhinos were the natural enemies of elephants, the animal, on Holy Trinity Day (June 7) in 1515, was forced to fight an elephant, although the fight did not then occur as the great proboscidean would flee. For Europeans of the time, seeing a rhinoceros was a bit like looking at a fairy tale animal, a beast that until then was known only through stories in literature: it is not a stretch to say that, for that time, seeing a rhinoceros was a bit like seeing a unicorn. Thus, Manuel I thought of strengthening his diplomatic relations with the Papal States by turning the gift over to Pope Leo X (who, moreover, already owned an elephant named Annone: it was also drawn by Raphael): the animal was then re-embarked in 1516 in the direction of Rome, and after a brief stop in Marseille so that Francis I, King of France, could also admire it, the ship wrecked in the Gulf of La Spezia, and the wreck also dragged the rhinoceros with it, which was chained and could not save itself. The unfortunate animal ended its days between January and February 1516, drowned in the waters off Portovenere, and the carcass was fished out some time later off Villefranche-sur-Mer, France: it still managed to reach the pontiff, since the rhinoceros was stuffed. It is then unknown what happened to it: it is said to have been destroyed during the sack of Rome in 1527, or transferred to Florence to enrich the Medici collections and then dispersed. The vicissitudes of the animal are also retraced by the humanist Paolo Giovio (Como, c. 1483 - Florence, 1552), who in his Dialogo dellimprese militari e amorose recalled how the rhinoceros was chosen for the emblem of Duke Alessandro de’ Medici: “He therefore asked me one day with instance that I wanted him to find a beautiful feat for the sopraveste darme according to this meaning. And I elected to him that fierce animal, which is called rhinocerote, the capital enemy of the elephant, which being sent to Rome, so that he might fight with it, by Emanuello King of Portugal, having already been seen in Provence, where he descended to land, he drowned by sea for unaspra fortune in the rocks just above Portovenere, nor was it ever possible for that beast to be saved, for being chained, even if he swam admirably, because of the preponderance of the very high rocks that makes all that coast.”

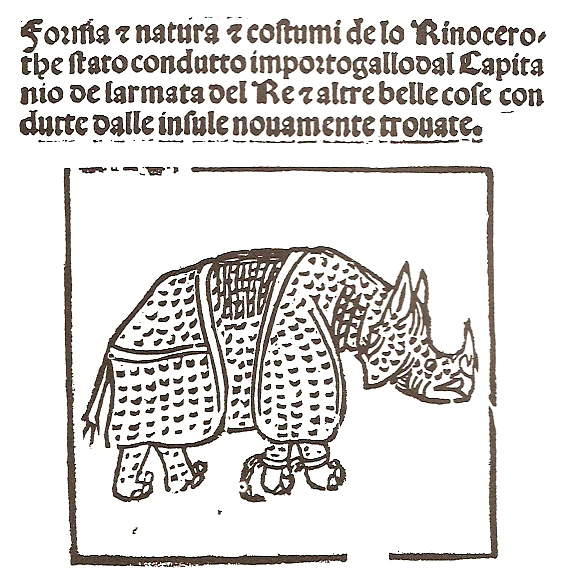

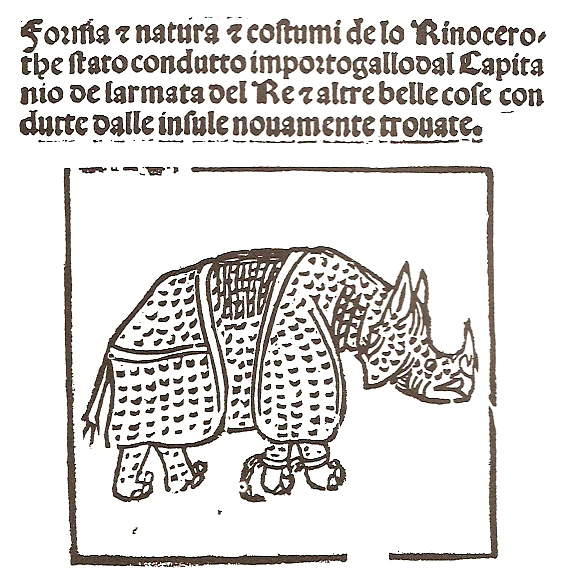

However, not many artists were able to see the rhinoceros, and Dürer himself, as mentioned, had to rely on his sources. News of the beast’s arrival had been spread by Valentim Fernandes (documented from 1495 to 1519), a Moravian-born but naturalized Portuguese printer who was among the first to see it after landing. In the summer of 1515 (in June or July), Fernandes had written a letter, written in German (his native language) and addressed to unspecified recipients living in Nuremberg, in which he described the prodigious animal. The original of the missive has been lost, but at the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze we preserve a contemporary Italian translation: “dear brethren, in the 20th of this month of Magio 1515 arrived here in Lisbon, cita nobilissima di tuta la Lusitania, emporio al presente excellentissimo, uno animale chiamato da greci Rhynoceros et dalli Indi Ganda, mandare dal re potentissimo de India della cità di Combaia a donare a questo Serenissimo Emanuel Re di Portogallo. Which animal, in the time of the Romans, Pompey the Great in his zuochi, as Pliny says, was shown in the circus with other different animals this Rhynoceron el quale dice haver uno corno nel naso et esser un altro inimico allo helephante che havendo a combatere con loro aguzia el corno a una prieta et nella bataglia se ingegna ferire nella panza per esser loco molto più debole et tenero dice essere lungo quanto uno helephante ma haver più curte gambe et esser di colore simile al bosso”. Fernandes, moreover, also offers evidence of the confrontation with the elephant mentioned above. Fernandes’s letter is important since Dürer was familiar with it, and used it to sketch the preparatory drawing of his rhinoceros, now in the British Museum (and moreover brought back an excerpt of Fernandes’s text at the foot of the drawing). The original letter probably also included some sketches that perhaps Dürer used for his drawing (although they have not survived). Another eyewitness was the Florentine physician Giovanni Giacomo Penni, who in 1515 published a poem entitled Forma e natura e costumi de lo Rinocerothe stato condutto im Portogallo dal capitano de la armata del re and altre belle cose condutte dalle insule novamente trovate: on the cover, his literary work bore a rudimentary illustration of the rhinoceros that Penni had seen in person (the effect aroused by the rhinoceros is well described in these endecasyllables: “in his junta el capitano presato / al Re di Portogallo suo signore / uno animale rubesto ha presentato / che ad vederlo sol mette terrore. / This one with his flesh is harnessed / firm skin and of a strange color, / as flaky as the legs of testudine / and withstands every blow like an anvil”). And again, a work (which Dürer did not see, since it is in Lisbon) executed by a sculptor who was able to admire the beast in Lisbon, is the rhinoceros-shaped relief that decorates one of the walls of the Tower of Belém in the Lusitanian capital.

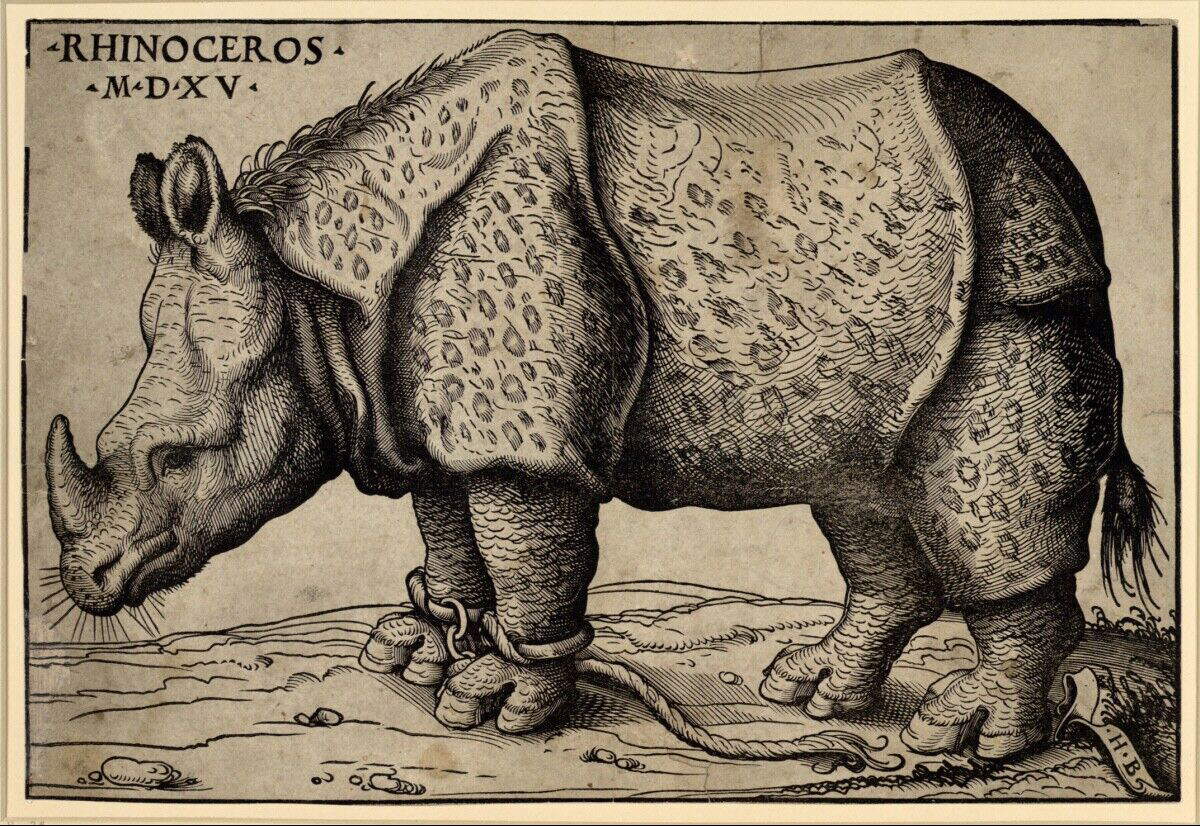

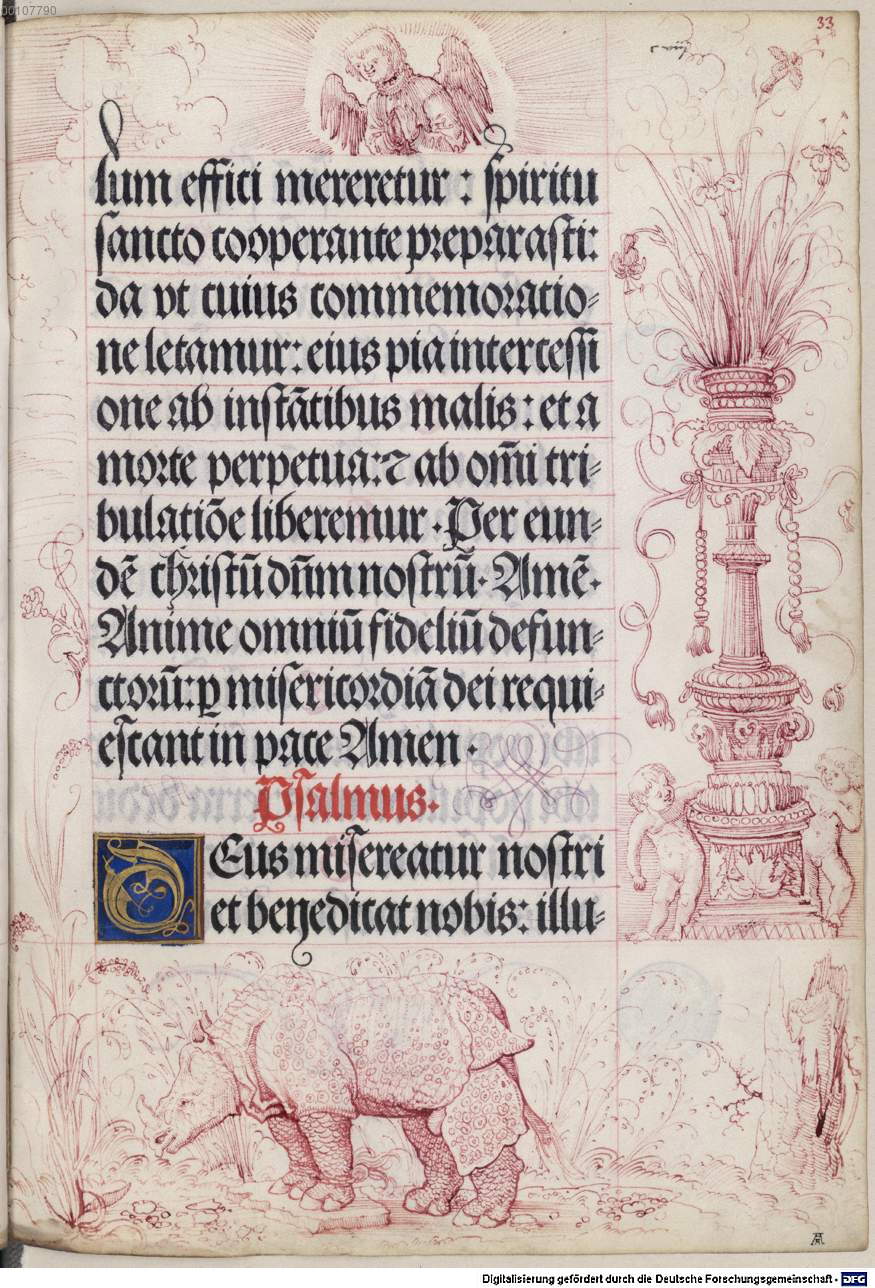

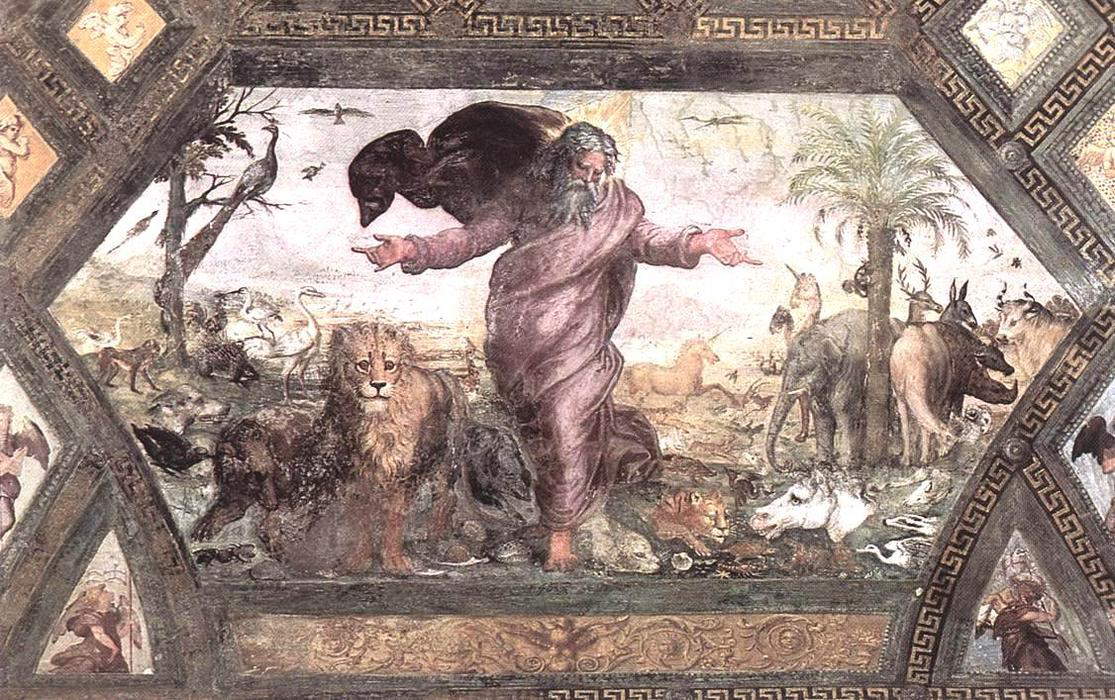

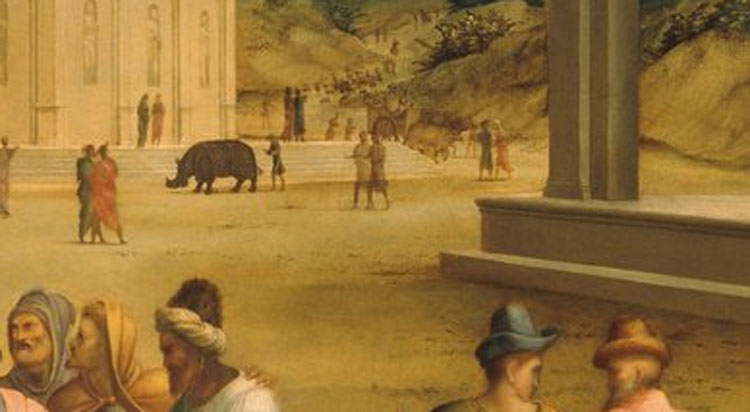

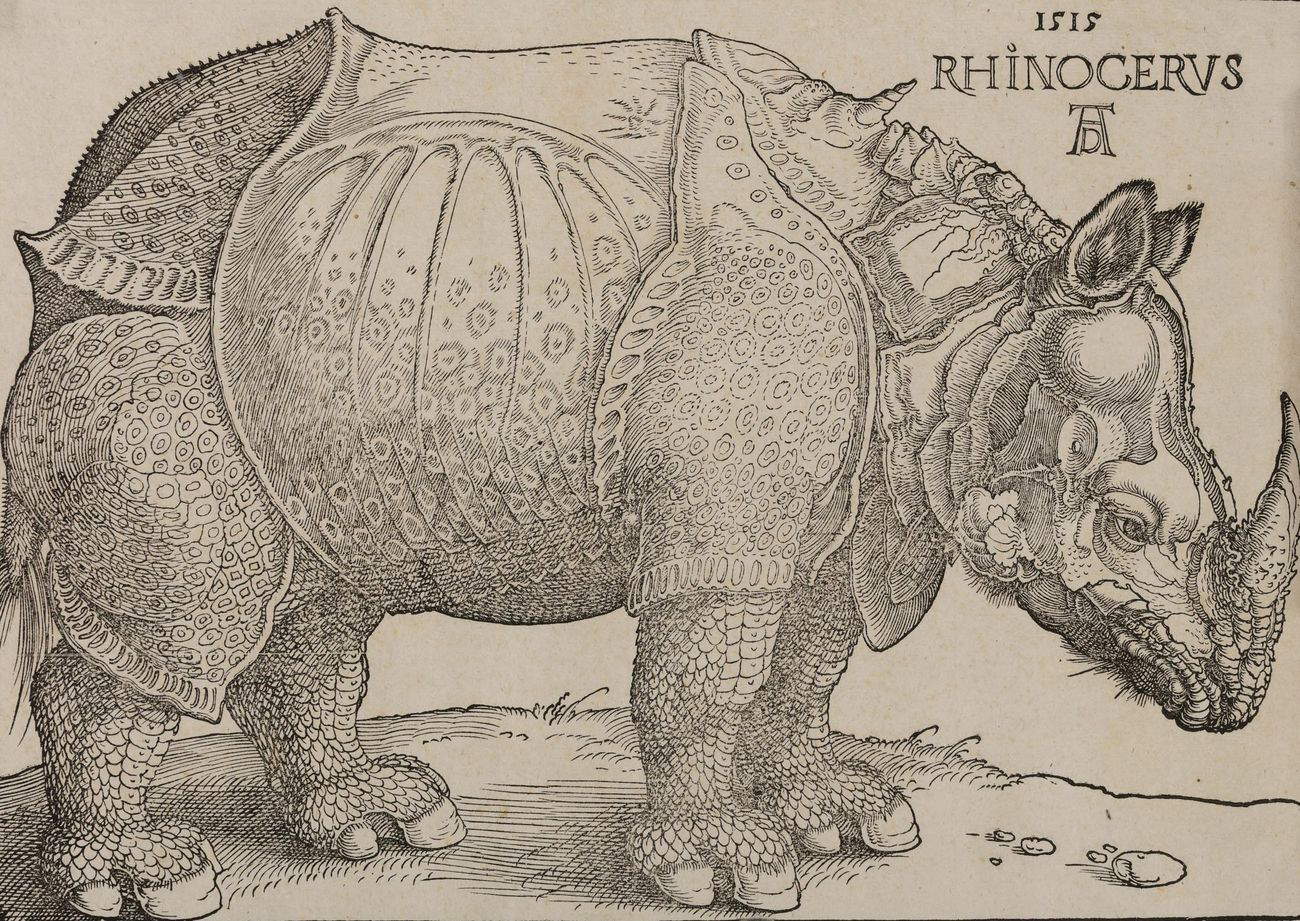

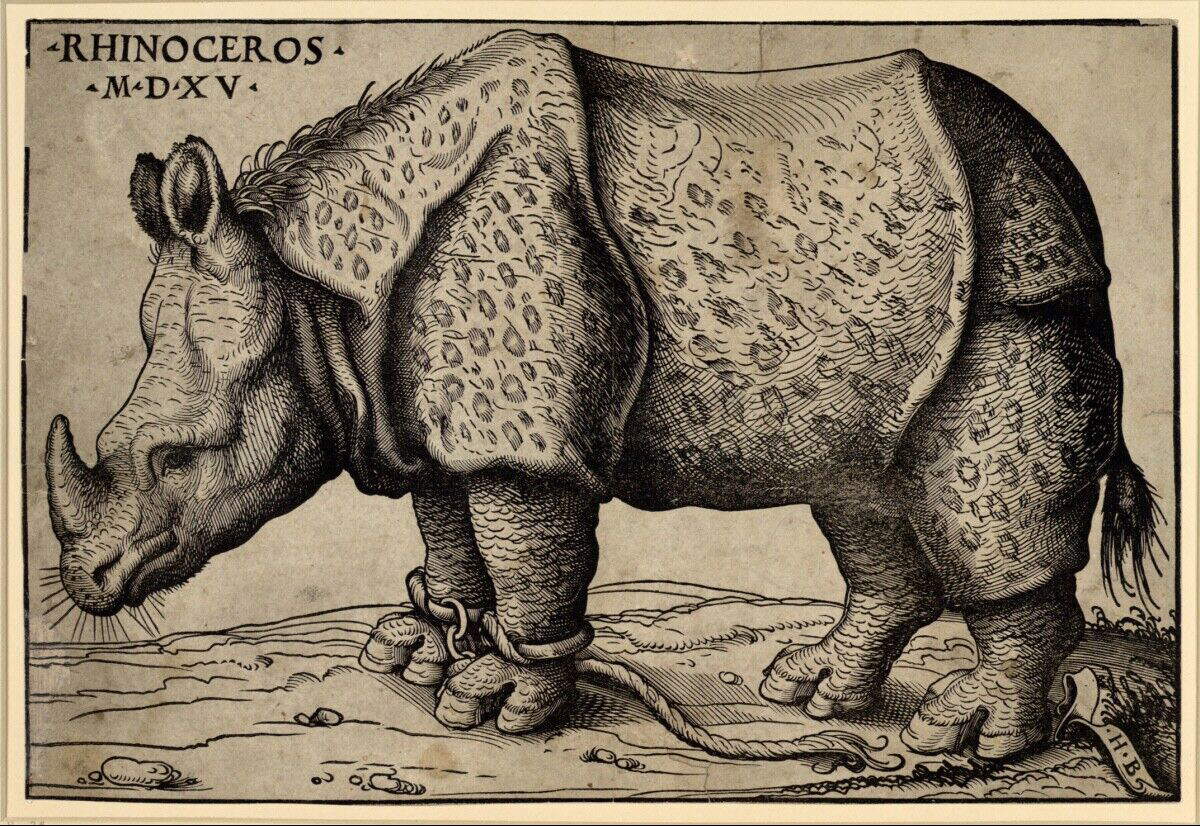

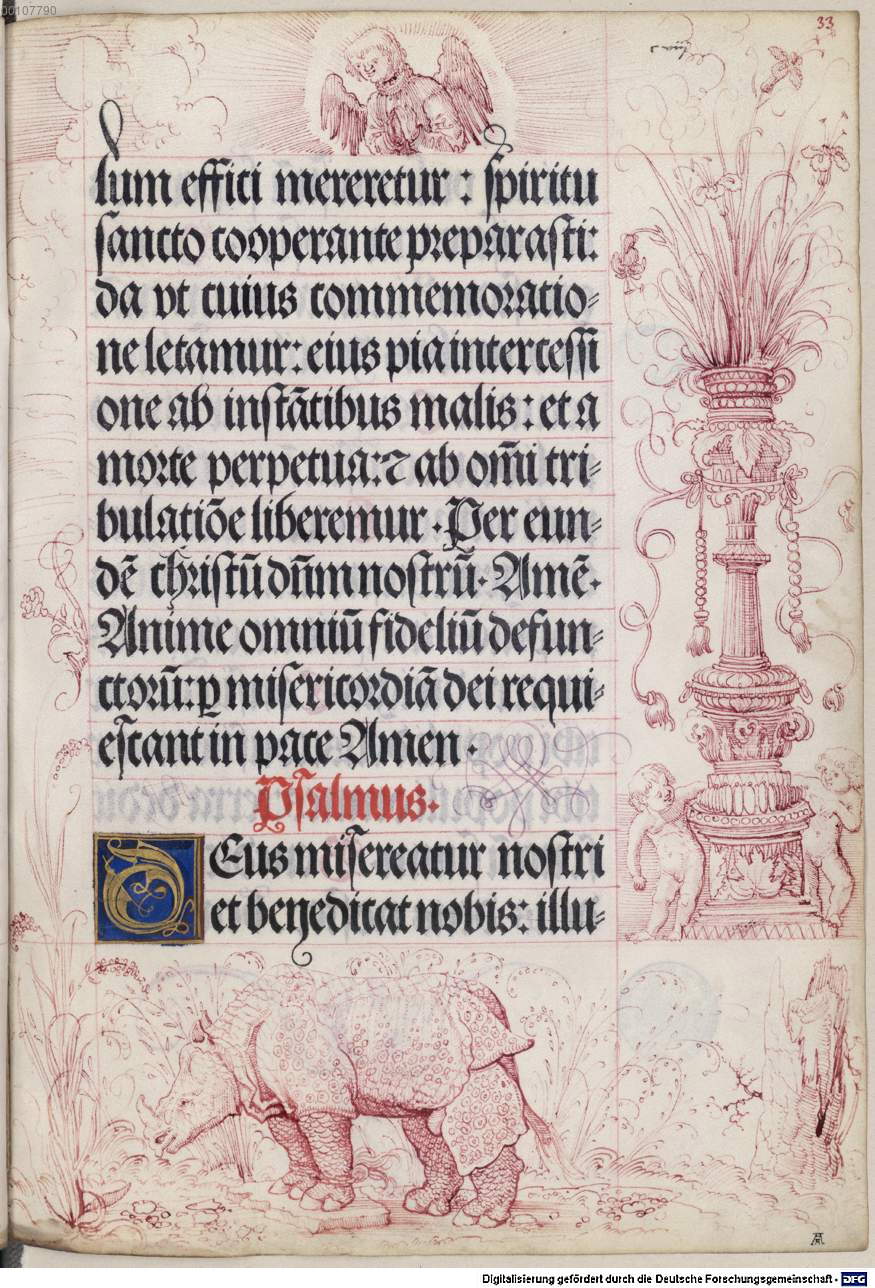

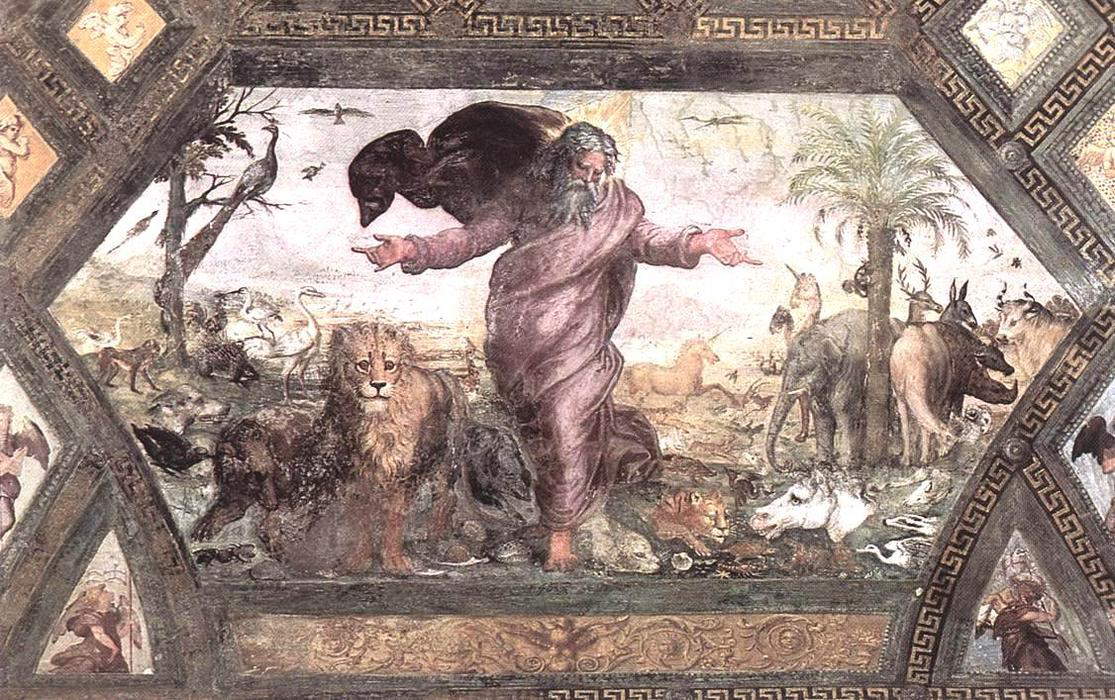

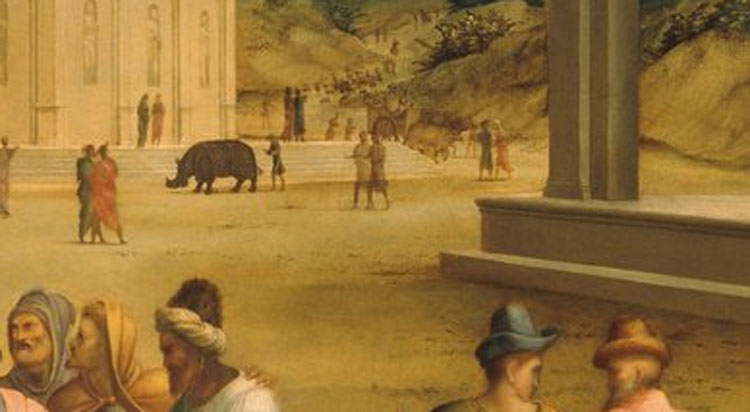

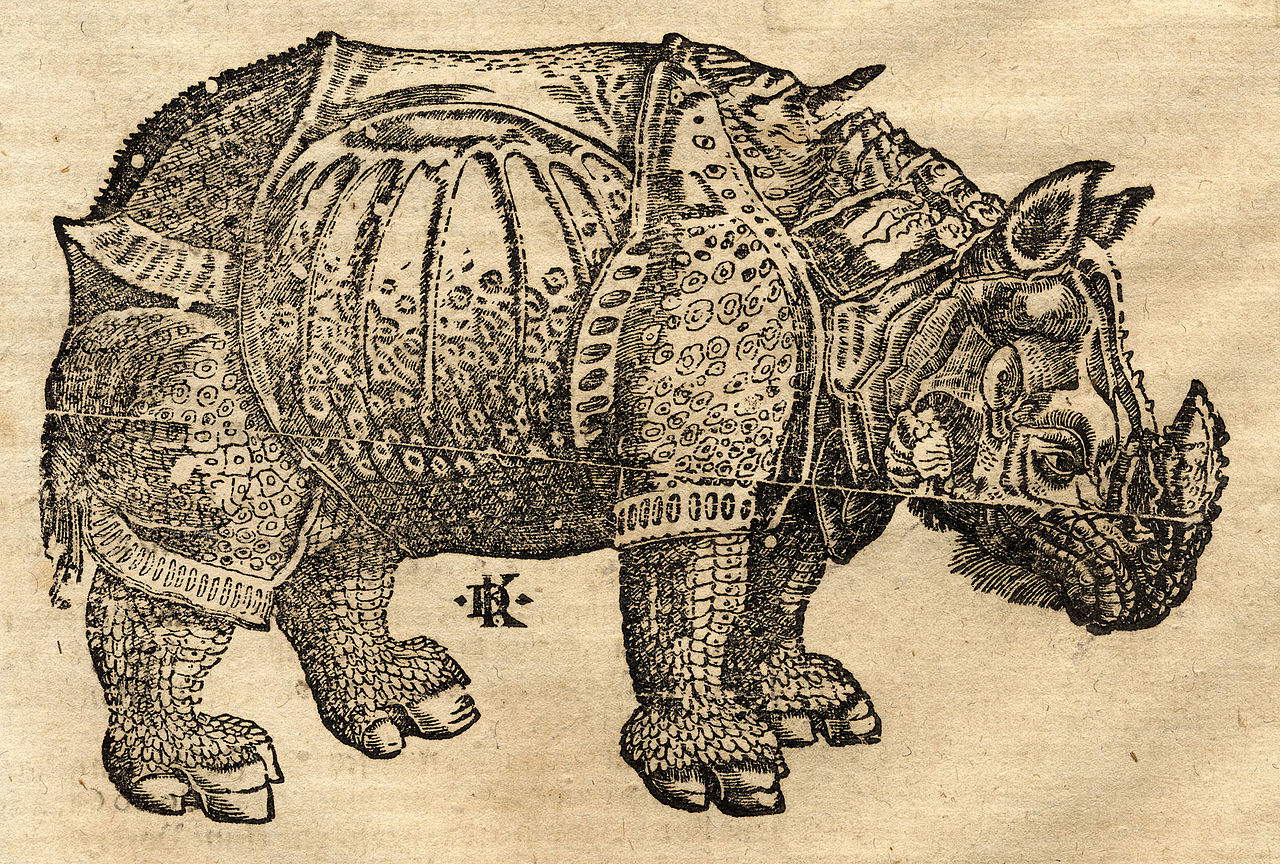

Among the earliest artists attracted to the rhinoceros can then be counted Hans Burgkmair (Augsburg, 1473 - 1531) who, also in 1515 like his colleague and friend Dürer, made a print depicting a rhinoceros, much more realistic than Dürer’s (although it must be said that we do not know what kind of correlation there is between the two works). Indeed, we see that the quadruped does not have the second horn on its back, the folds of the skin are less stylized and geometric, the scales on the legs turn into more naturalistic wrinkles, the outgrowths on the body are more irregular, we also see the animal chained. The fact that Burgkmair’s engraving (which survives in a single copy, preserved in the Albertina in Vienna) is closer to reality suggests that the Augsburg artist probably relied on the same sketches that Dürer had been able to see. “Midway” in a sense between Dürer and Burgkmair is the rhinoceros depicted on the Book of Hours of Maximilian I(Kaiser Maximilians I. Gebetbuch), a prayer book made in 1515 for the emperor: assigned to the workshop of Albrecht Altdorfer (Regensburg, c. 1480 - 1538), it is considered independent of Dürer despite the similar presence of the dorsal horn (it should not be forgotten that many ancient authors, such as Martial and Pausanias, having seen African rhinoceroses spoke of two horns, and one can make the hypothesis that Dürer was familiar with the ancient texts and, given also the fact that some Renaissance humanists commented on the rhinoceros texts by pointing out the discrepancy between those who spoke of one horn and those who spoke of two horns, equivocated them), and shares with Burgkmair’s engraving the wrinkled appearance of the legs, the longer neck than Dürer’s, the stumps at the legs, and the appearance of the tail. And again, another rare sixteenth-century rhinoceros independent of Dürer’s is the one depicted by an anonymous illustrator who included it in an incunabulum of Pliny’s Naturalis historia, now preserved in the Palatina Library in Parma: this drawing, too, is much more realistic than Dürer’s, but we have no idea how the unknown Parma artist knew the rhinoceros. Instead, we can get an idea of how Raphael (Urbino, 1483 - Rome, 1520) and Francesco Granacci (Bagno a Ripoli, 1469 - Florence, 1543) saw it: the former included it in a fresco, created with his collaborator Giovanni da Udine (Udine, 1487 - Rome, 1561), depicting the Creation of the Animals in the Vatican Loggias, while the latter included it in one of the panels for Pierfrancesco Borgherini’s wedding chest, now in the Uffizi, depicting Joseph presenting his father and brothers to Pharaoh (the animal is in the background giving a touch of exoticism to the scene). Both Raphael and Granacci certainly had occasion to see the stuffed rhinoceros in Rome, delivered to Leo X after it was shipwrecked in Porto Venere and found in Villefranche-sur-Mer.

|

| Albrecht Dürer, Rhinoceros (1515; woodcut, 214 x 299 engraved, 254 x 303 mm sheet, specimen with Dutch inscription from the sixth edition published in The Hague c. 1620; London, British Museum) |

|

| Albrecht Dürer, Rhinoceros, preparatory drawing (1515; pen and brown ink on paper, 274 x 420 mm; London, British Museum) |

|

| Giovanni Giacomo Penni, Forma e natura e costumi de lo Rinocerothe (1515; print; Seville, Biblioteca Colombina) |

|

| Portuguese Sculptor, Rhinoceros (1515; Lisbon, Tower of Belém) |

|

| Hans Burgkmair, Rhinoceros (1515; engraving, 213 x 317 mm; Vienna, Albertina, Graphische Sammlung) |

|

| Workshop of Albrecht Altdorfer, Rhinoceros, from the Book of Hours of Maximilian I, fol. 33v (1515; Besançon, Bibliothèque Municipale) |

|

| Raphael and Giovanni da Udine, Creation of the Animals (1518-1519; fresco; Vatican City, Vatican Loggias) |

|

| Francesco Granacci, Joseph presents his father and brothers to Pharaoh, detail (c. 1515; tempera on panel, 95 x 224 cm; Florence, Uffizi) |

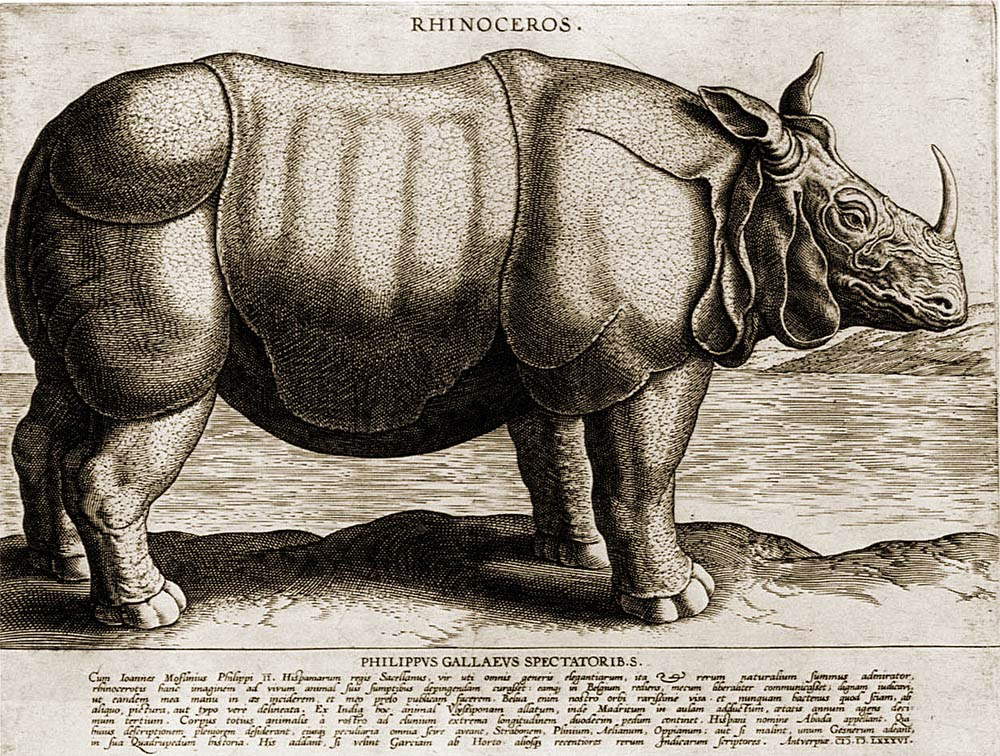

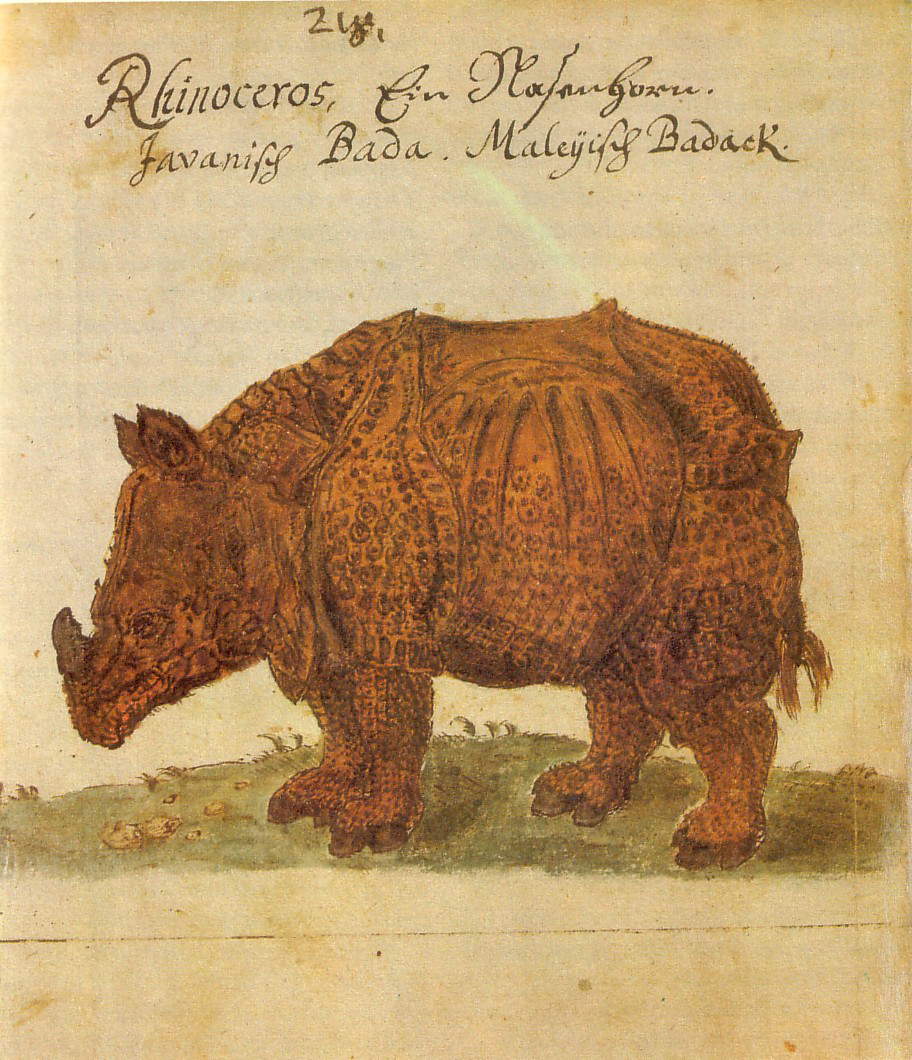

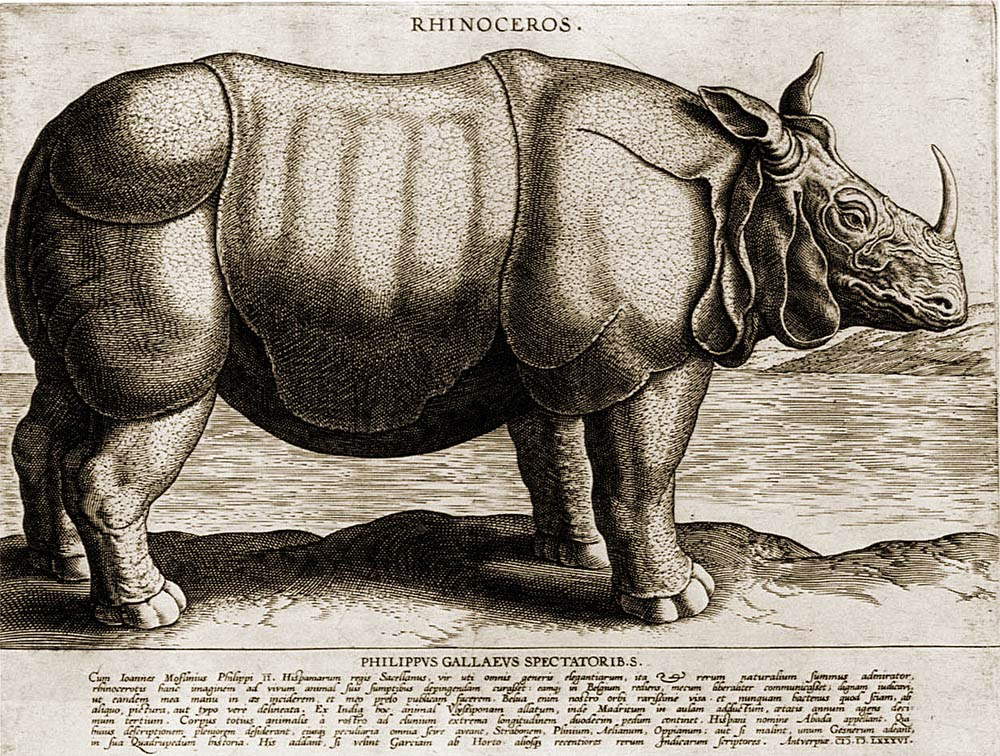

As scholar Rosalba Dinoia notes in the catalog of the Bagnacavallo exhibition about Dürer’s Rhinoceros, “it appears quite evident that the animal’s features do not correspond exactly to reality,” since the animal has a horn on its back, “the skin seems to resemble an armature, covered as it is with scales and imbricated plates; on its neck it has a ruff and its legs are covered with scales.” in essence, “the whole suggests an armor forged on the occasion of the fair’s confrontation with an elephant when he was at the court of Manuel I, but one can also assume an imaginative rendering of the artist who wanted to restore in the skillful play of the carving of the wooden block not so much the real features as the idea of a strong and solid animal, responding over a long period of time to the expectations of the collective imagination.” Dürer’s image had a vast fortune (“resounding and uncontrolled” Giovanni Fara calls it), and for more than two centuries it formed one of the rare bases for representations of the Indian pachyderm, despite the fact that in the 1570s another rhinoceros, named Abada, had arrived, lived from 1577 to 1580 in the gardens of the Portuguese kings Sebastian I and Henry I and from 1580 to 1588 in those of Philip II of Spain, and depicted in a realistic illustration by the Dutch engraver Philippe Galle (Haarlem, 1537 - Antwerp, 1612) in 1586 (which, however, had little luck). There are indeed a great number of works illustrating rhinoceroses based on Dürer’s highly successful woodcut, as opposed to those that were inspired by Burgkmair’s engraving instead: the latter include the Marine Map that cartographer Martin Waldseemüller (Freiburg im Breisgau, 1470 - Saint-Dié-des-Vosges, 1520) produced in 1516, which curiously places the Indian rhinoceros in Africa. The greater success of Dürer’s print can be explained, hypothesizes scholar Colin T. Eisler, on the basis that his work is certainly more fascinating than Burgkmair’s, and consequently, despite its more fanciful appearance, it managed to appeal more to his contemporaries and beyond, since the echo of the Rhinoceros reverberated for at least two centuries. And obviously in Dürer’s favor played the commercial success that explained its wider circulation, since his work experienced multiple print runs and reprints, as opposed to Burgkmair’s, which had only one impression.

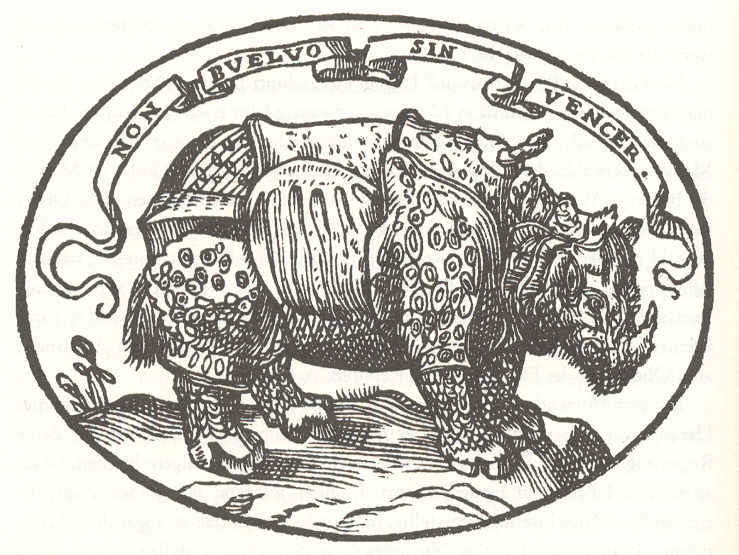

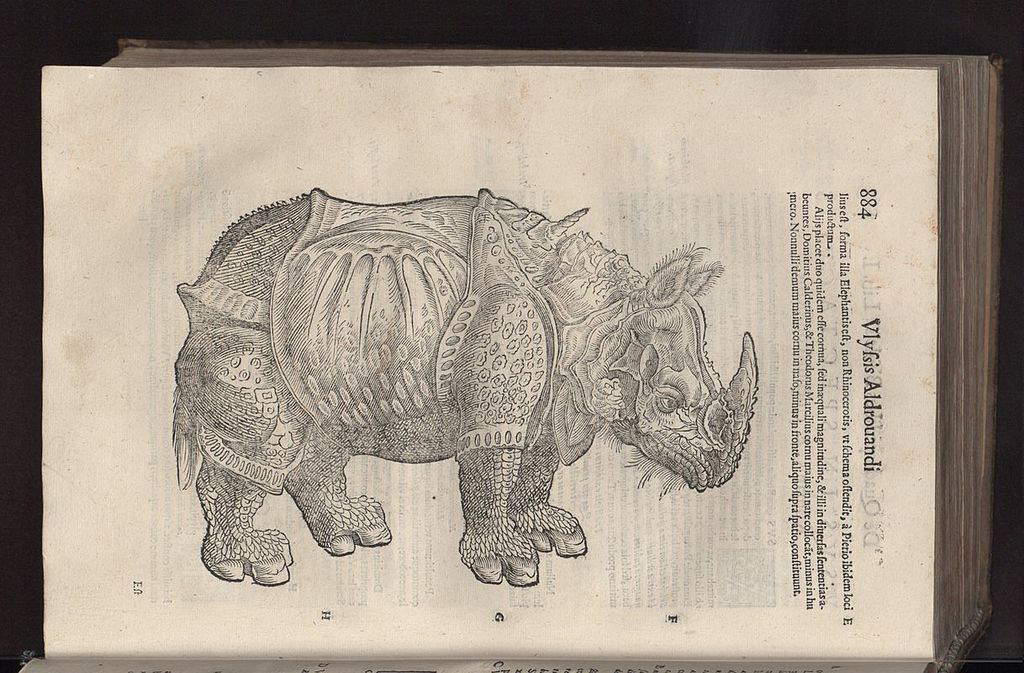

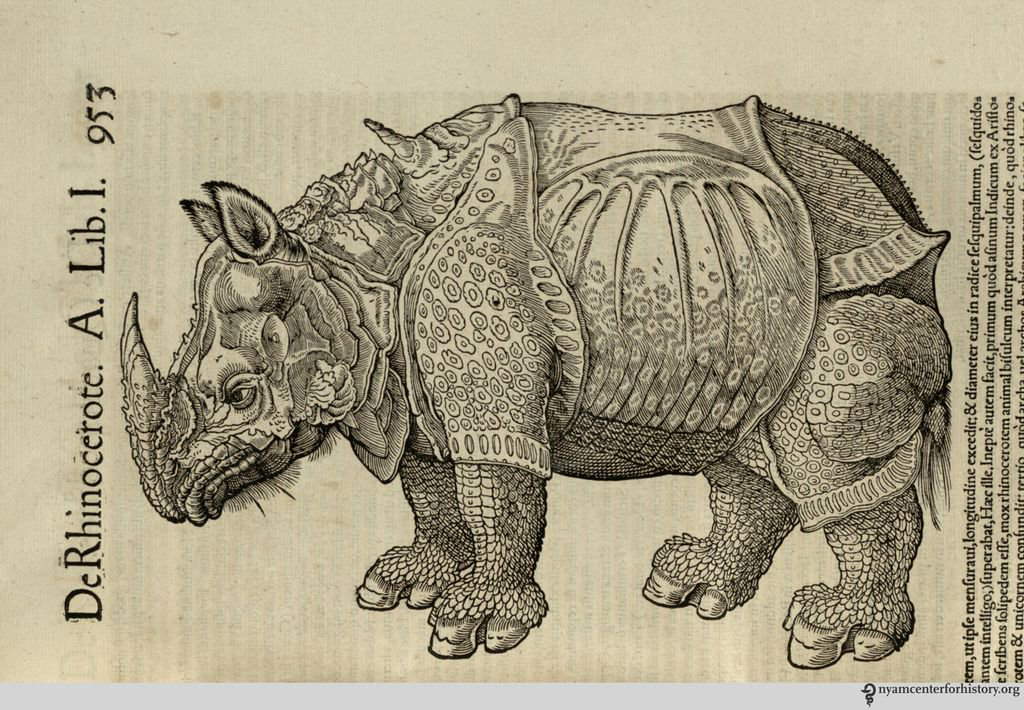

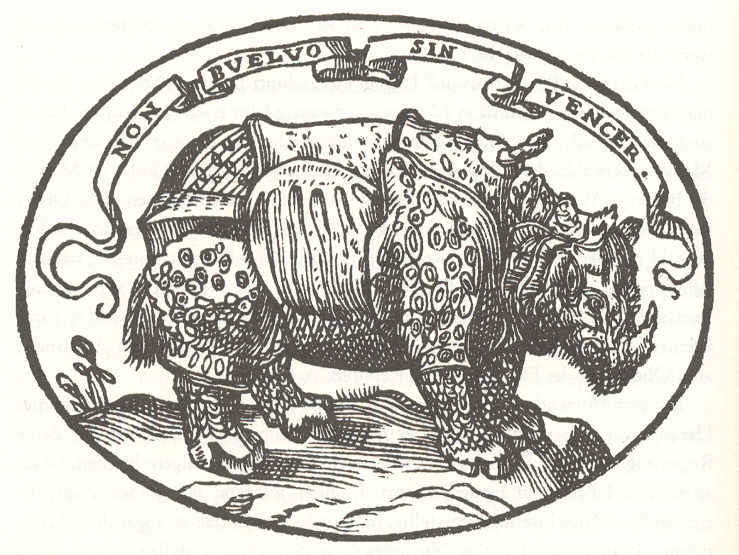

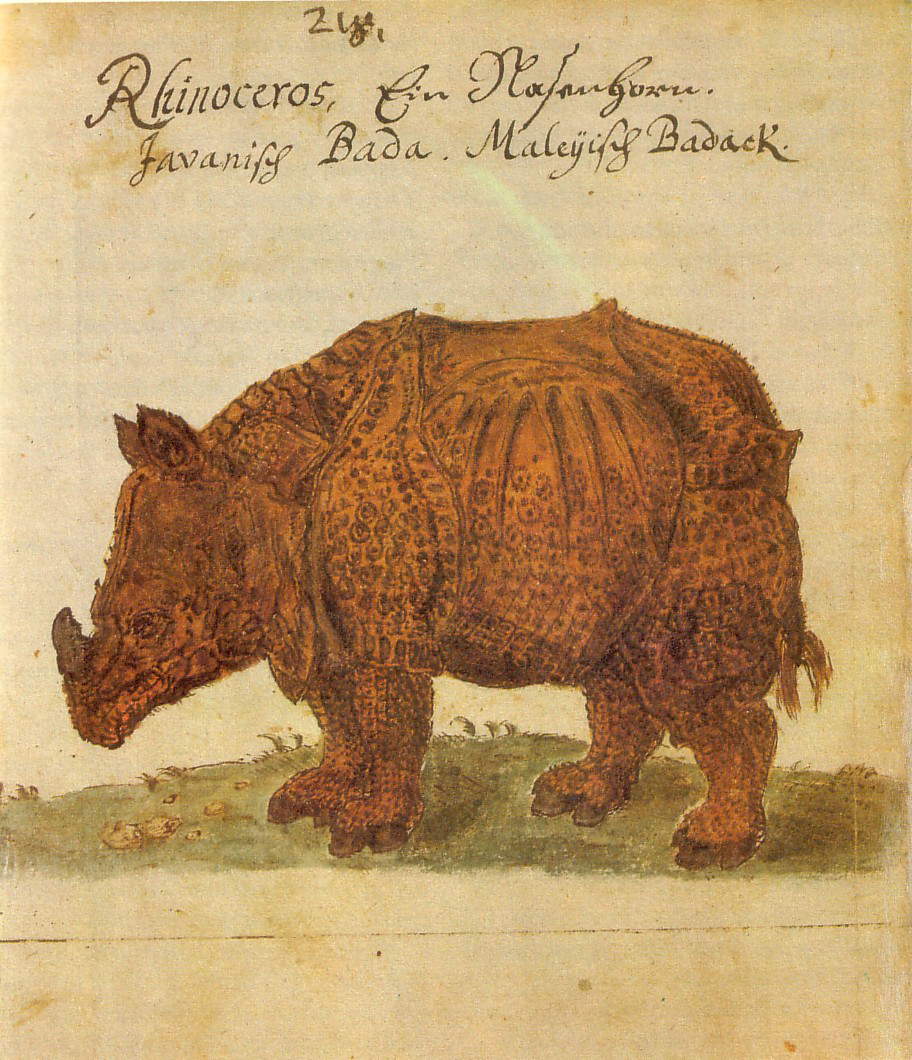

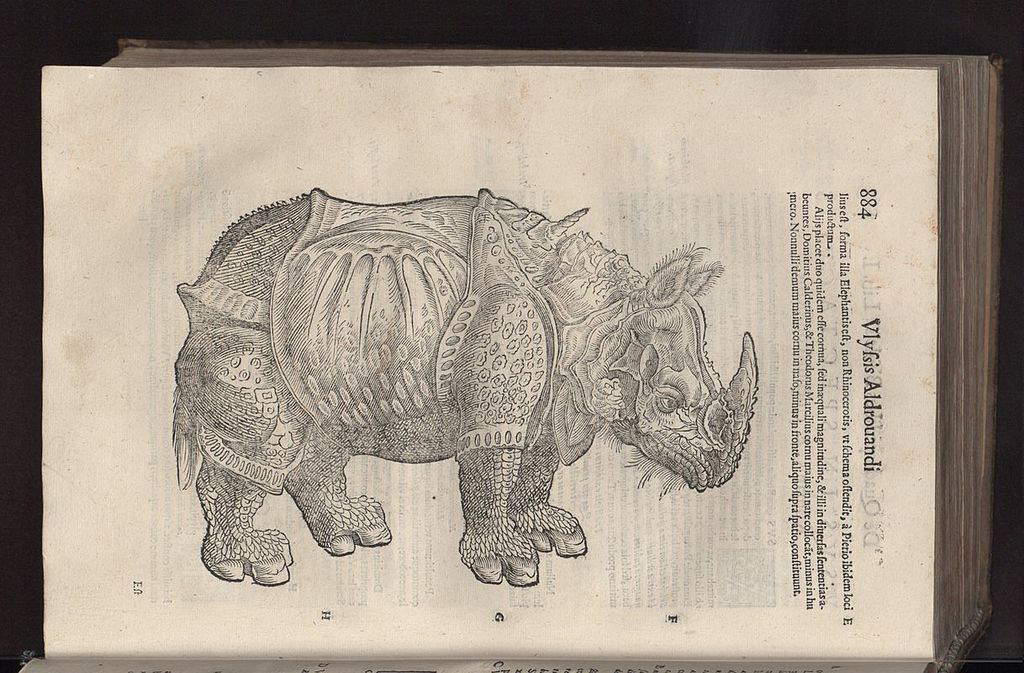

As mentioned, among the earliest attestations of the fortunes of Dürer’s Rhinoceros is Alessandro de’ Medici’s enterprise, which depicts the animal along with the motto Non vuelvo sin vencer (“I do not return without winning”): Giovio himself explained that the motto in Spanish was derived from a Latin verse (“Rhinoceros numquam victum ab hoste cedit,” or “The rhinoceros never returns vanquished by his enemy”), which the humanist does not attribute to any author, but it is conceivable that it was his invention since in one of his works this verse is quoted as part of a couplet that decorated a room in his residence. Still 16th-century is the rhinoceros that the Flemish Abraham de Bruyn (Antwerp, 1538 - Cologne, 1587) included, in 1578, in a series of depictions of the animals of the world, engraved in frieze form. Another artist who echoes Dürer is one of the initiators of botanical and faunal art, the German David Kandel (Strasbourg, 1520 - 1592), whose rhinoceros is included in Sebastian Münster’s Cosmographia of 1598. We then find Dürer’s rhinoceros in a Flemish tapestry kept in Denmark’s Kronborg Castle, circa 1550, one of the earliest color representations of the fair. Another rhinoceros in color is the one depicted by the traveler Caspar Schmalkalden (Friedrichroda, 1616 - Gotha, 1673): Schmalkalden was actually in Asia but it is not known whether he saw a live rhinoceros; what is certain is that his beast, while distancing itself from Dürer’s by the absence of the dorsal horn, takes up some features of the 1515 engraving (for example, that sort of ray-shaped decoration on the back). In Italy, too, there is important evidence of the fortunes of Dürer’s Rhinoceros: we find it modeled in the grotto of animals at the Villa Medicea di Castello, on the outskirts of Florence; we find another in bronze, the work of some follower of Giambologna (Jean de Boulogne; Douai, 1529 - Florence, 1608), in one of the panels of the left portal of the cathedral of Pisa; and a naturalist such as Ulisse Aldrovandi (Bologna, 1522 - 1605) also made use of it for his Quadrupedum omnium bisulcorum historia published posthumously in 1621. Aldrovandi was not the only scientist who relied on Dürer: we also find his rhinoceros, in fact, in the Historia animalium by Swiss Conrad Gessner (Zurich, 1516 - 1565), published in the 1550s.

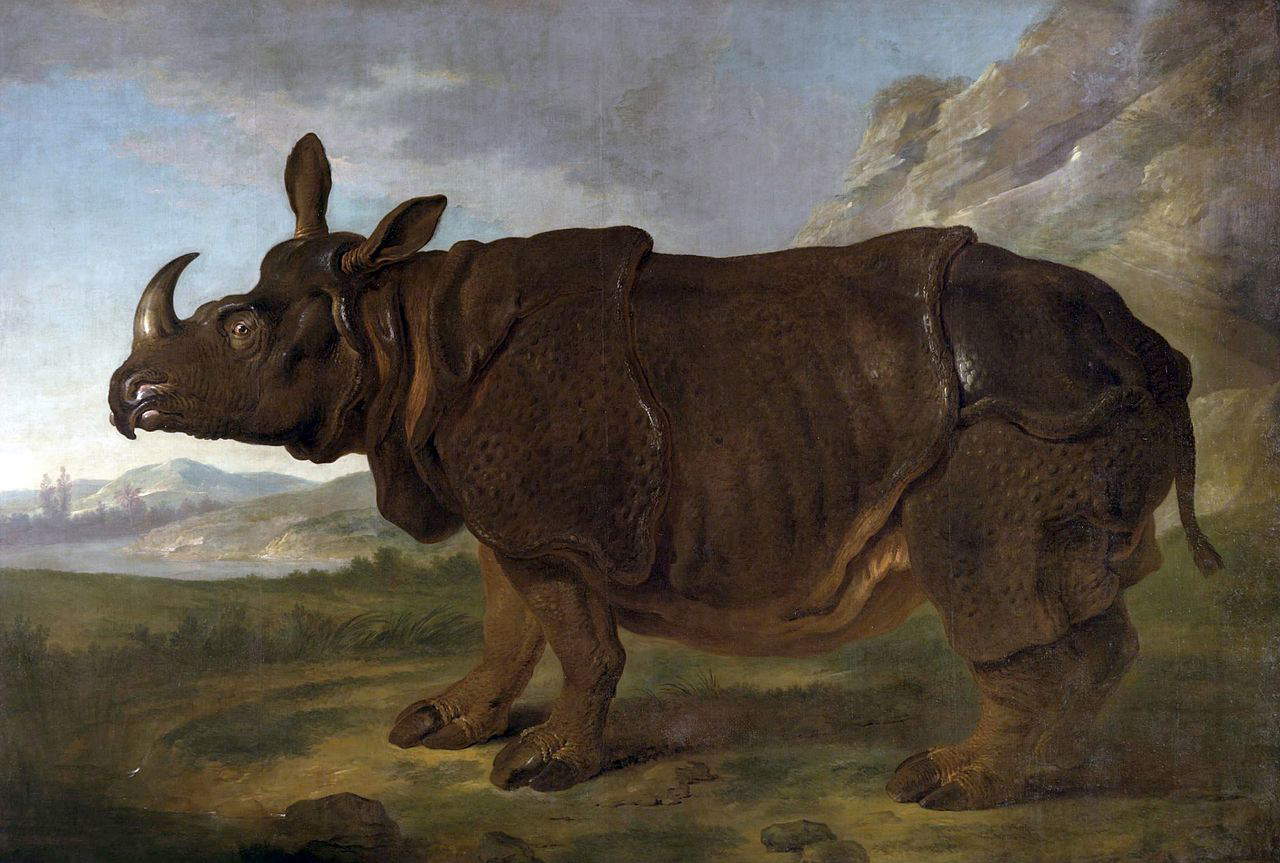

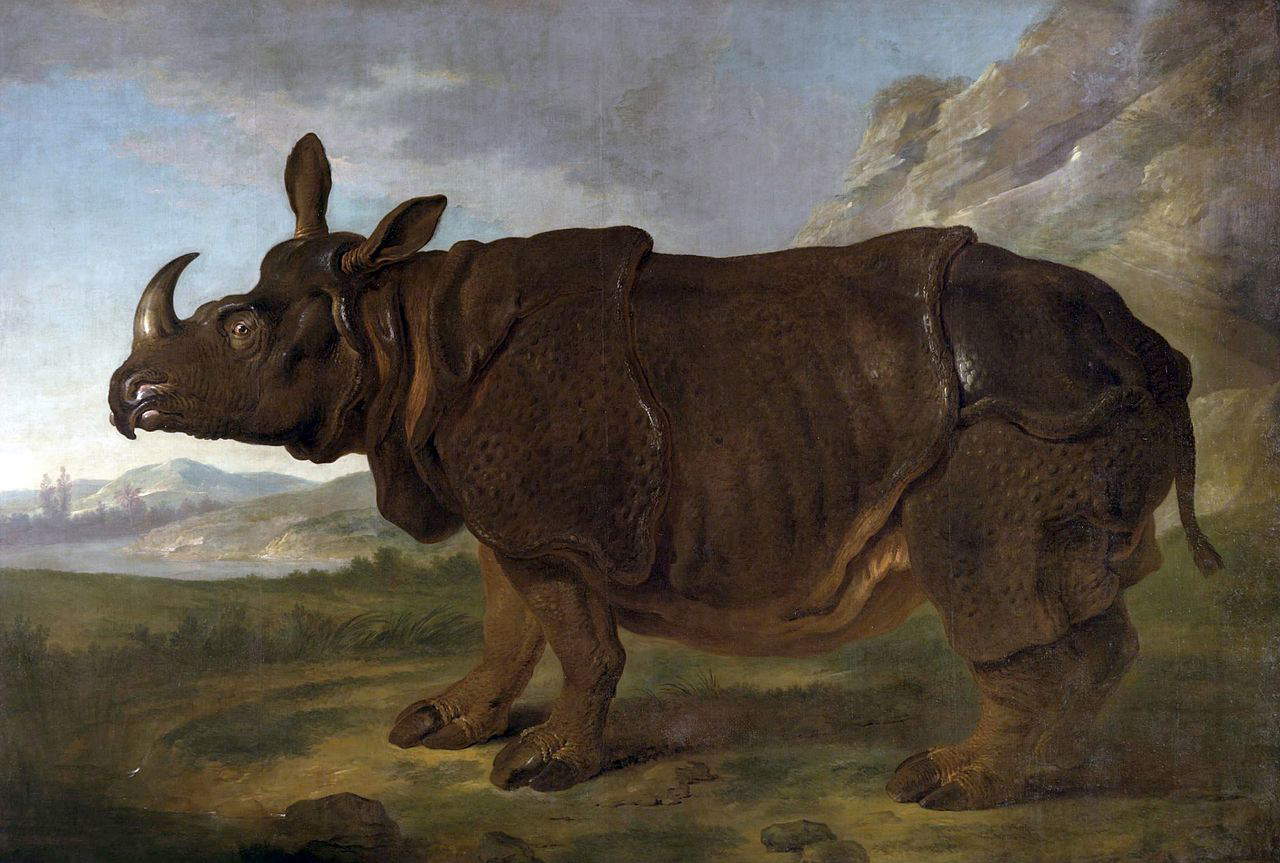

We have to reach the eighteenth century to find another rhinoceros that caused the same stir as that of King Manuel I: it was a female specimen, Clara, landed in 1741 at the port of Rotterdam (she was brought to Europe by an officer of the Dutch East India Company, Douwe Mout van der Meer, who later made his fortune simply as the animal’s owner). Clara was the fifth rhinoceros to come to Europe from Manuel I’s animal: for seventeen years, until her death in 1758, Clara toured Europe constantly, as if she were a kind of rock star, often becoming an attraction for the public, since she was exhibited at numerous shows. Here, too, the depictions are innumerable: we need only recall the canvas by Jean-Baptiste Oudry (Paris, 1686 - Beauvais, 1755), which sets her in a meadow, or the very famous one by Pietro Longhi (Venice, 1701 - 1785), where Clara is the most striking attraction at the 1751 Venice carnival.

|

| Philippe Galle, Rhinoceros (1586; engraving; private collection) |

|

| Martin Waldseemüller, Sea Chart, detail from sheet 6 (1516; woodcut, sheet 455 x 620 mm; Washington, Library of Congress) |

|

| The Motto of Alessandro de’ Medici from Paolo Giovio’s Dialogo dell’imprese militari et amorose (Venice, 1557) |

|

| Abraham de Bruyn, An elephant, a dragon, a reptile, a rhinoceros, a goat and two giraffes (second half of the 15th century; engraving, 52 x 21 mm; London, Wellcome Collection) |

|

| David Kandel, Rhinoceros (illustration from Sebastian Münster’s Cosmographia published in 1598; Private Collection) |

|

| Dutch Manufacture, Tapestry with Rhinoceros (1550; Kronborg, Kronborg Castle) |

|

| Caspar Schmalkalden, Rhinoceros, illustrated panel from the West- und Ost-Indianische Reisebeschreibung (1642-1645; color illustration; Gotha, Schloss Friedenstein) |

|

| Niccolò Pericoli called the Tribolo, Giambologna and others, Cave of Animals (1540-1541; sculptural group; Florence, Villa Medicea di Castello). Ph. Credit Francesco Bini |

|

| School of Giambologna, Rhinoceros, panel of the left portal of Pisa Cathedral (1595-1602; bronze; Pisa, Duomo). Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| The rhinoceros illustrated in Ulisse Aldrovandi’s Quadrupedum omnium bisulcorum historia (published 1621) |

|

| The rhinoceros illustrated in Conrad Gessner’s Historia animalium (published 1551-1558) |

|

| Jean-Baptiste Oudry, The Rhinoceros Clara in Paris in 1749 (1749; oil on canvas, 310 x 456 cm; Schwerin, Staatliches Museum) |

|

| Pietro Longhi, The Rhinoceros (1751; oil on canvas, 62 x 50 cm; Venice, Ca’ Rezzonico, Museo del Settecento Veneziano) |

It has been said that naturalists also looked with keen interest at Dürer’s engraving, and it was precisely this relationship with the sciences, in relation to the Rhinoceros, that was the subject of an in-depth study by scholar Elena Filippi on the occasion of the Remondini Collection exhibition held in Bassano in early 2019. “Measurement and drawing,” writes the art historian, "constituted for Dürer an indispensable method of access to reality, and he strove so that his description of living beings possessed an objective value and conformity, responding to geometric criteria and just proportions. His studies of plants and animals, however [...] went beyond the accurate rendering of the naturalistic aspect. Even his rhinoceros is an example of how he put into practice the request he addressed to art, namely, to make visible the outward features of things(natura naturata) and to expose their essence(natura naturans).“ Filippi asserts that ”the Dürerian Rhinoceros marks an epochal turning point“ in that it ”makes manifest a new dynamic between artistic experience and the datum of nature“ and because it marks ”a transformation of the concept of imitation" at a time when it was the very nature of art that was being debated: that is, the intellectuals of the time were debating whether art should be merely imitation, or whether the creator’s foreignness should be manifested in the final product. Dürer’s Rhinoceros, therefore, is not only a work that enjoyed enormous success, but could also be considered a kind of symbol of its time.

And indeed, the work, as mentioned, experienced great success, due to “both chance and genius” of the artist, according to Tim H. Clarke. Dürer was only in time to see a single edition of his Rhinoceros, since the fortunes of the woodcut were mostly posthumous: two more editions date from the fifth decade of the sixteenth century, and it was the editions of the 1940s that ensured the work’s greatest circulation. Two more editions followed in the last years in the century, and in the meantime the work had begun to cross the borders of Germany, for there are also two editions printed in Holland, from the original matrix. And to this day, the Rhinoceros continues to be one of the great German artist’s most curious and discussed works.

Reference bibliography

- Diego Galizzi, Patrizia Foglia, Albrecht Dürer. The Privilege of Disquiet, exhibition catalog (Bagnacavallo, Museo Civico delle Cappuccine, from September 21, 2019 to January 19, 2020), Ceribelli editore, 2019

- Chiara Casarin and Roberto Dalle Nogare (eds.), Albrecht Dürer. The Remondini Collection, exhibition catalog (Bassano del Grappa, Musei Civici, April 20 to September 30, 2019), Marsilio, 2019

- Maria Agata Pincelli, The Humanists and the Rhinoceros via Dürer in Machtelt Israëls (ed.), Renaissance Studies in Honor of Joseph Connors, Officina Libraria, 2013, pp. 445-452

- Giovanni M. Fara, Albrecht Dürer: originals, copies, derivations, Olschki, 2007

- Colin T. Eisler, Dürer’s animals, Smithsonian Institute Press, 1991

- Hermann Walter, Contributions on the Humanistic Reception of Ancient Zoology. New documents for the genesis of Albrecht Dürer’s 1515 RHINOCERVS in Picene Humanistic Studies, IX (1980), pp. 267-277

- Tim H. Clarke, The rhinoceros from Dürer to Stubbs, Sotheby’s Publications, 1986

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.