by Federico Giannini (Instagram: @federicogiannini1), published on 04/01/2018

Categories: Works and artists

- Quaderni di viaggio / Disclaimer

Asger Jorn lived and worked for years in Albissola Marina: the Jorn House Museum, what was once his home, preserves the poetry of his art.

The road that starts from the seaside village and climbs the hills that serrano it from behind, among palm trees, olive trees and dry stone walls, led in the 1950s to a wasteland and an abandoned farmhouse, dating from who knows what era. Those sunny slopes that rise from Albissola Marina had been the place where two popes, Sixtus IV and Julius II, spent their childhood: it is probable, therefore, that even that poorly preserved building might once have been part of an agricultural estate that belonged to the della Rovere family, who originated in this territory.

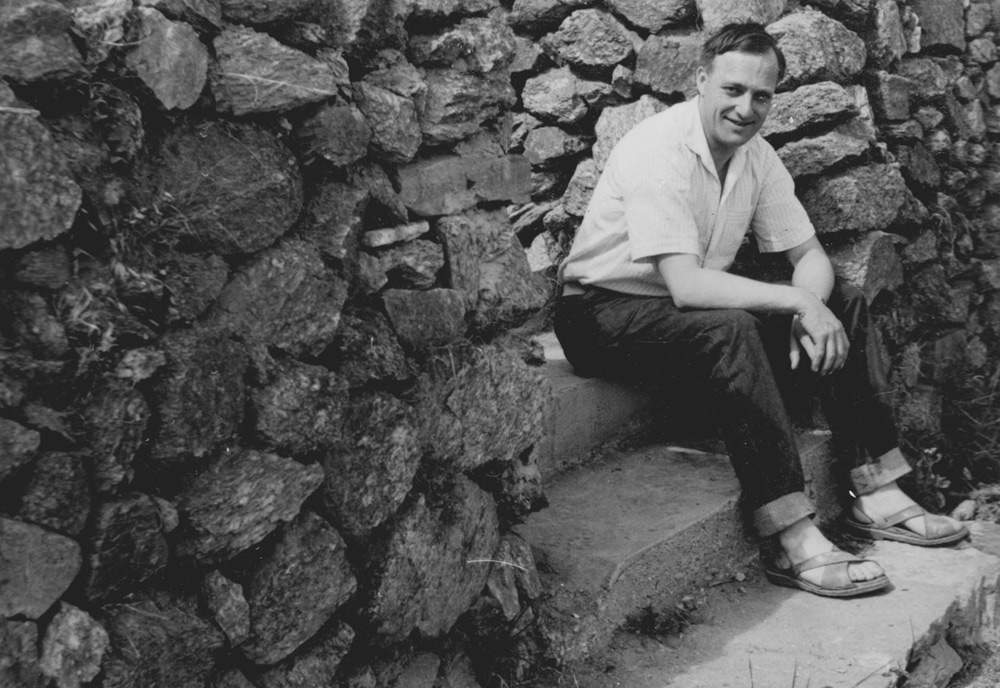

From up here there is a wide panorama of the sea. You can see all of Albissola, but your gaze also embraces the port of nearby Savona and, on the opposite side, the small promontory that separates the city of ceramics from neighboring towns. In the 1950s, building expansion had just begun to bite this stretch of the Ligurian coast, and the view, compared to today, certainly encountered fewer obstacles. But the scent of pine trees, the chirping of cicadas, the relaxing tranquility remained unchanged. An environment as suitable as ever for an artist’s reflections: so much must have been on the mind of the great Asger Jorn (Vejrum, 1914 Aarhus, 1973) when, in 1957, he decided to settle in that old house of stones and bricks, as soon as economic conditions allowed him to move to a place more welcoming than those to which he had been accustomed since his arrival in Italy.

|

| The view from the garden of Casa Jorn. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

Three years earlier, the artist had accepted an invitation from Enrico Baj and Sergio Dangelo, with whom he had long established correspondence. Jorn had always shown a certain hostility to functionalism: “the artistic impulse,” he wrote as early as 1943, “is the center of our imagination and intuition. It is what unites our realities with our potential, what exists with what does not exist, what has been with what is coming but has not yet arrived, the possible with the impossible. It is what allows us to rise above questions concerning time and space. It is something fundamental in our nature, because it strengthens our will to live and to create.” His polemic against a style that he believed was guilty of suppressing the artist’s creative flair led him to found, in 1954, the Mouvement Internationale pour un Bauhaus Imaginiste, which aimed to recreate the community spirit of Gropius’s Bauhaus, to oppose the drifts of the group founded in Weimar (and drift was considered Max Bill’s much-maligned “new Bauhaus”), to grant trust and importance to the artistic expression of the individual, and to stand against the excess of rationality typical of functionalism. Baj joined the movement, and Jorn was enthusiastic about moving to Italy: Albissola Marina was suggested to him by Baj himself, because several of his friends, including Lucio Fontana, frequented it, and the Milanese artist, although he had never been there in person, had always heard good things about it.

Jorn, however, had nowhere to sleep. In the spring of 1954, when he arrived in Albissola Marina together with his partner Matie and their children Olga, Martha, Ole and Bodil, he first ended up as Lucio Fontana’s guest in his fund in Pozzo Garitta, the picturesque little square in Albissola’s historic center, and come summer he camped on land owned by Marquis Faraggiana, in the Grana district, not far from Albisola Superiore. Literally: the lodging of the “Viking,” as Baj used to call him, was nothing more than a camp tent. But it was comfortable nonetheless: in a letter sent in 1997 to Piero Simondo, his daughter Martha (née Nieuwenhujis) recalled that the tent was “almost as big as a bungalow,” spacious, late-model, Danish-made, accommodated six people who slept wide inside. And it was even equipped with a veranda. The winter quarters, on the other hand, was the studio that Asger had taken on Isola Street: “a huge room,” Martha wrote again, “equipped with services, divided in two by a wooden wall, in which we stayed comfortably.” The studio was located near the kilns where ceramics were made: the Danish artist had come to Albissola with the clear intention of delving into this technique, which he considered particularly conducive to his way of understanding art.

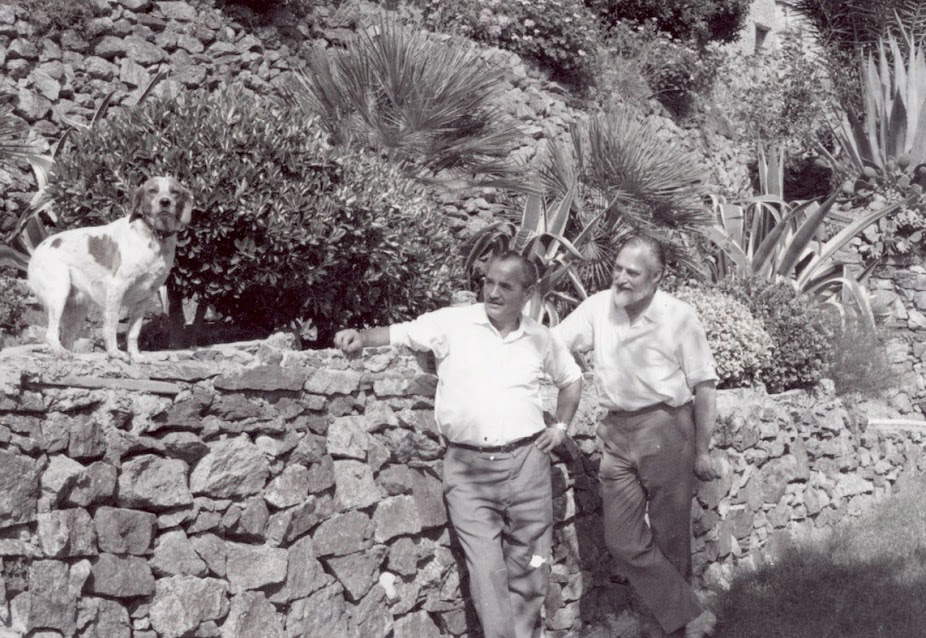

Barely three years passed from the time Asger Jorn landed in Liguria to the time he managed to buy the land and the house on the hill, in the Bruciati district: the proceeds from the sales of the works certainly did not allow him to live in luxury, but he was able to take the satisfaction of having a house of his own, and above all of fixing it up in the manner he considered most suitable. And he did his utmost to make the house itself a great work of art. In Albissola Marina, Asger forged a firm and deep friendship, destined to last until the end of his days, with a local craftsman, Umberto Gambetta (but for everyone, simply, Berto), who helped him rearrange the ruin. “For years,” Martha recalled, Berto “would devote every spare moment in restorations and embellishments that, in a crescendo, would transform our house with garden into a house-museum.” Berto, skilled with masonry work, was entrusted by Asger to take care of the walls, walls and floors. The artist, on the other hand, created the ceramics that would decorate the rooms. Everything was to be cozy, colorful, a dwelling where it would be pleasant to live, work, host friends and colleagues for long reflections in the garden, perhaps over a good glass of wine. Wine that Jorn himself, as a great enthusiast (especially of Piedmontese wines), produced from the grapes that Berto and his wife Teresa provided him. “Dear Asger,” Berto wrote him in a letter dated January 24, 1973, “your letter that reached me today left us very saddened knowing you are hospitalized. You tell me that you miss wine and minestrone very much, for the wine I have sent you a small package with two bottles of Barolo ’64 and one of Barbera ’67 which I hope will be good and will please you, for the minestrone nothing to do, we are waiting for you in Albissola to eat it together, you will understand, hot they say it is better.”

Unfortunately, Asger would never return to Albissola: the tribulations inflicted by lung cancer got the better of him, and the artist passed away on May 1 in Aarhus, Denmark. But his friendship with Berto had already been eternalized with a particularly poignant work. Leaning against the annexe in which the artist wanted to place his studio, we see an oven whose hood was decorated by Asger with a mosaic made by means of the Ligurian technique of rissêu: typical of churchyards and gardens, it called for the image to be composed with strictly black and white pebbles, recovered from rivers or the shoreline. On the front of the hood is one of the many strange figures that populate the residence. On the right side, Asger composed the inscription “BERTO / JORN.” It is a way to seal this special bond between the “foresto,” as they say in these parts, and the native, between the globetrotting artist and the worker, between the kind-hearted Viking and the Ligurian who nullified stereotypes about the mistrust of the inhabitants of this land (along with almost all the people of Albissola, who never failed to support the artist who came from afar). But also a way to “sign” that great work of art that is Casa Jorn.

|

| Casa Jorn in Albissola Marina. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte. |

|

| Exterior of Casa Jorn. Ph. Credit Friends of Casa Jorn |

|

| The entrance to the museum. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Asger Jorn and Berto Gambetta. Courtesy Amici di Casa Jorn |

|

| The kiln with the mosaic. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Berto and Jorn’s signature. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

A home that has now become the Jorn House Museum, directed with expertise, passion and acumen by Luca Bochicchio. It was the artist himself who wanted the house to become a museum. His last will stipulated that, after his departure, the house be granted free use, for life, to Berto and Teresa. Then, once their passing had also occurred, the house, already donated to the City of Albissola Marina, would be turned into a museum. And so it was: undergoing a long and complex restoration, which began in the early 2000s and ended in 2014, the year of the centenary of Asger Jorn’s birth, it was opened for public viewing on May 3.

“It is important to understand that poetry is not just something outside the essential needs of life, but that bread and wine are poetic, that a house is a poem and a city is an ornament, a precious jewel.” Asger Jorn’s words find their fulfillment already on the first steps leading from the street to the garden and then to the house. In every corner of the house one breathes poetry. The exterior floors are layered with ceramic fragments brought in from Ceramiche Artistiche of Santa Margherita Ligure. Tatters of various shapes, sizes and colors, combined to form one of the most bizarre mosaics you can walk on: what for others is waste, for Asger Jorn is possibility. Nothing is thrown away: from paintings by amateur artists found in flea markets to tiles recovered from the manufactories of half of Liguria, everything is good for creating a new work of art, in accordance with that principle of “revaluation” (as the scholar Karen Kurcynski calls it) that animated the poetics of Asger Jorn, interested as he was in popular artistic expressions as they are charged with a spontaneous creativity, far from both the academies and the avant-garde. “Jorn created for himself and his family,” writes Luca Bochicchio, "a spontaneous architecture, in which painting, sculpture, applied and decorative arts merged, creating a continuum with the forms and colors of nature. That is why every part of the walls, floors and buildings contains traces of artistic interventions, often made with salvaged materials and objects: scraps from glass, marble, kilns, tiles, river stones, shells, antique vases and, of course, plates and sculptures by Jorn and his friends." Outside the house, monsters of all sorts placed on the exterior walls with clear apotropaic functions. These are, for the most part, figures that hark back to Norse mythology (but not only that: there is also a small cave in the garden that houses, three hundred and sixty-five days a year, a Christian terracotta nativity scene): for Jorn, myth is an interesting manifestation of collective creativity, and the artist’s task is not to believe myths (a passive action wholly unsuitable for an artist), but to create myths.

|

| An excerpt from the exterior floor of Jorn House. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| One of the monsters on the exterior walls. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| The nativity scene. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

The first floor of the dwelling is a kind of visual manifesto of these concepts. Of the monsters that populate the exterior, it has already been mentioned. Inside, the first room the visitor encounters is the kitchen, one of the rooms most experienced by Jorn and his guests. Here, there are ceramic tiles and kitchen utensils, all sourced from local workshops. Some are probably antique ceramics as well. Also on the walls are sketches for two monumental works: the Great Relief for the Aarhus State High School (1959) and the Great World for the Randers House of Culture (1971). A panel illustrates the stages of making the Great Relief. For Albissola Marina, it was something of an event, given the size of the work (a colossal ceramic sculpture three meters high and twenty-seven meters wide) and also given the unorthodox techniques the artist had put in place to create it: a famous image depicts him going over the clay with his white Vespa. A gesture intended to make the artistic creation itself a kind of performance, an action that made clear how the very act of creating is dictated by a drive. The figures that the visitor finds in the next room, a veranda that connects the ground floor with the second floor, also respond to the same impulse: similar to those that populated the art of Jean Dubuffet, the artist malgré lui par excellence, they are formed from stones and fragments of ceramics that create bizarre characters that seem to have come out of the mind of a child. And with children Jorn was particularly at ease.

This is evidenced by the ceramics that hang on one of the living room walls upstairs. They are plates made by Asger Jorn’s children when they were still children, in 1955, during an experiment carried out as part of an imaginist Bauhaus congress. Placed within one of the most important rooms in the house, because for the Danish artist, art produced by a child was something to be taken very seriously. The artist Aksel Jørgensen (Copenhagen, 1883 - 1957), with whom Jorn had worked extensively as a young man, wrote that “the child is not restrained or hindered by psychological knowledge, and no one asks him to subordinate his natural need to create to this kind of knowledge. The child stands alone in the midst of the world and perceives everything around him only with his own eyes and without reflection. [...] The child has no clear concept of the physical existence of the world, and so he lives according to what his thoughts are.” And Jorn, who felt the same way, wrote that “a child who loves beautiful figures and pastes them in a book with the words ’ALBUM’ imprinted on it, infuses the artist with greater hope than any art critic or museum director could give him.” It is not surprising, then, that the Danish artist made much of his artistic endeavors inspired by children’s doodles, nor is it surprising that his children participated in decorating the house. Quite simply, he believed that children were capable of far more spontaneous and free artistic manifestations than those adults who were constrained within certain patterns because of acquired knowledge, matured skills, and aesthetic convictions that had become conscious.

And he, in his works, tried as much as possible to work with the same amazement as a child. He tried to imagine, and to make imagine, those who observed his works. Like the ones we find in the bedrooms. This is how Luca Bochicchio describes them: “In the murals we see here we can see the expressive, gestural and chromatic charge of Jorn’s painting. From the apparent chaos of lines, smears and drips of color, deformed figures seem to emerge that we can reconstruct or interchange in our minds. According to Jorn, visual art, as well as architecture, was meant to interact with the viewer by stimulating his or her imagination and fantasy. Public and decorative art were even more important to Jorn, as they could change the perception of space by positively affecting life.” The style is typical of the artists of the Co.Br.A. group: violent lines, strong colors that blend, indefinite forms, but never totally detached from reality. In Jorn’s own definition: "anabstract art that does not believe in abstraction."

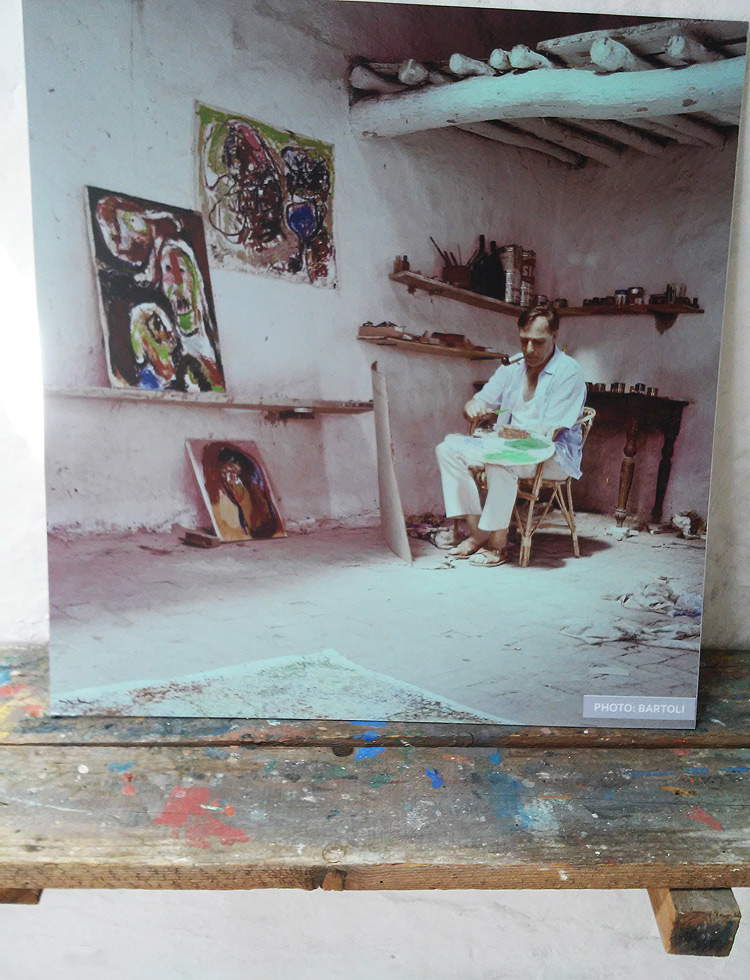

One leaves the main building and continues to the annex. There is a large pool in the garden that was originally intended to convey rainwater: it would later be used to irrigate nearby fields. Blooming lilies lead toward the building in which Asger Jorn wanted to set up his studio. The smaller room had been set up as a thinking room: the artist would retire there when he wanted to enjoy some quiet time alone. And when he was absent, the small room was granted to Berto and Teresa, who could use it as a bedroom. The larger room, on the other hand, is a large mezzanine classroom: this is where the artist painted, and some photos on the walls testify to the use of this part of the dwelling. The table on which Jorn rested his paintings to let them dry is still present.

|

| The kitchen of the Jorn House. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Asger Jorn, Untitled, kitchen (ca. 1959-1960; kiln rejects; Albissola Marina, Jorn House Museum) |

|

| Exterior of the veranda at night. Ph. Credit Friends of Casa Jorn |

|

| Detail of the veranda. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Asger Jorn, Untitled, veranda (ca. 1959-1960; kiln waste and mixed media; Albissola Marina, Jorn House Museum) |

|

| The living room of the Jorn House. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Detail of the living room with, on the right, the children’s plates. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Asger Jorn’s Children, Plate, Second Imaginist Bauhaus Experiment (1955; terracotta painted under paint, 29 x 26 cm; Albissola Marina, Jorn House Museum) |

|

| Asger Jorn, Mural, bedroom (1960s; acrylic painting; Albissola Marina, Jorn House Museum) |

|

| Asger Jorn, Mural, bedroom (1960s; acrylic painting; Albissola Marina, Jorn Museum House) |

|

| Garden tub. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte. |

|

| The lilies in bloom. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| The think tank. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Photo of Asger Jorn in his studio, leaning against the table he used to let paintings dry |

Today, what was once Asger Jorn’s studio has become a venue for temporary exhibitions. In fact, exhibitions are also held at Casa Jorn, by established artists as well as young people who are beginning to make their way in the art world: the Association of Friends of Casa Jorn, which is responsible for the enhancement of the complex, is composed of young professionals who have an interest in keeping the quality of the events held there high. Not only exhibitions: also meetings, book presentations, performances, concerts. As well as a permanent collection housing a hundred works by Asger Jorn (in case considering the house a work in itself is not enough), and an active and vibrant contemporary art research center. A museum born thanks to an attentive city administration and a group of scholars with clear ideas, capable of working around a cultural project of the highest level, capable of satisfying insiders as well as visitors and art lovers. And all in the spirit of that great Danish artist who, one day in March 1954, arrived in Albissola Marina to write a new and rich page of art history. A page that, at Casa Jorn, can be read in all its ambitious and warm poetry, delicate and energetic at the same time.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.