Gothic and Baroque: that is how the style of Adolfo Wildt (Milan, 1868 - 1931) has been defined by leading critics contemporary with him. Indeed, standing before most of his masterpieces, the observer is certainly struck by the characteristic forms of his sculptures, by the dramatic and, one might almost say, caricatured features of the faces of the subjects depicted. And he is captivated by the luminosity emanating from the marble of his works, a material favored by this early 20th century artist: a light that spreads over the entire marble surface, which is extremely smooth, polished, and epidermal.

Writer and art critic Margherita Sarfatti (Venice, 1880 - Cavallasca, 1961) declared in her famous book Segni colori luci, published in 1925: “Adolfo Wildt, the first master of the art of marble that Italy has today, is the heir of the ancient marble workers and stonecutters for the vigilant and precise perfection with which he engraves without weakness in the glossy and hard material, the sign of his will. He polishes it with infinite love, makes it precious like a gem, carves black and cruel shadows in it. So much has he overcome the difficulties of technique, so much has he subdued the material, that he enjoys bending it with meticulous piety, and with the love and rancor of passion. She tends to nullify its weight and texture, and transfigure it all into spirituality of expression. He tilts sometimes toward a Baroque and Spanish-like torment; sometimes he recalls the angular and sorrowful Gothic; two epochs, the 1600s of decomposed virtuosity, the 14th century of architectural rigidity, one and the other transmogrifying in the spasm. His work can be debated, but it is a personal, true and moving work of art.”

This celebration was accompanied by Wildt’s joining, in the same year, the Steering Committee of the “Novecento Italiano,” a group directed and supported by Sarfatti herself, and founded on the original “Group of Seven,” composed of Anselmo Bucci, Leonardo Dudreville, Achille Funi, Gian Emilio Malerba, Piero Marussig, Ubaldo Oppi and Mario Sironi. These were united by the desire for a return to order after the avant-garde season: an order that was inspired by classical antiquity and purity of form. Arturo Tosi, Funi, Marussig, Sironi, Alberto Salietti, Margherita Sarfatti herself and Adolfo Wildt belonged to the aforementioned Steering Committee, which was formed in 1924 when the Novecento group presented itself at the 14th Venice Biennale: their aim was to give the movement a national character, a goal they later achieved in 1926 and 1929, on the occasion of their two major exhibitions in Milan (the first from February to March in the Palazzo della Permanente, the second from March to April in the same venue). Sarfatti regarded Wildt from that moment on as the greatest and most original interpreter of the Italian tradition.

Another great art critic and journalist who recognized this link between Baroque and Gothic in the artist was Mario Tinti (1885 - 1938). Speaking of Wildt’s style, he wrote, “the animated style arises from the need to go further and further, to shout and sing more. Wildt confesses that he almost prefers the head of Bernini’s Saint Theresa to Michelangelo’s David, or at least understands in it the more driven search for animation. Wildt admires masterpieces of sculpture the more they are soaring in sentimental expansion, the more they are cantilevered for shadow enhancement. Thus this style has served in an extraordinary way to give artistic form to pain, for as much in the miserable figure as in the harmonious and serene one, pain is not so vividly concretized as in the agitated violence: Wildt’s art may be regarded, in this respect (the stylistic aspect, of the means of expression) as a development of the baroque; but of the best baroque which is not degeneration of the classical, but free and enthusiastic outpouring of the imagination, which is related by its search for character to the Gothic, and which prepares modern art, tending to render all the mobility and spirituality of life.”

And again Ugo Ojetti (Rome, 1871 - Fiesole, 1946), another writer, art critic and journalist, dedicated a long article entitled Lo scultore Adolfo Wildt (The Sculptor Adolfo Wildt ) in the magazine Dedalo in 1926 to Wildt, where he stated that this “desire of his to pierce and lighten and make marble almost capable of floating is a character of Gothic sculptors.”

Exemplary of this seemingly irreconcilable marriage of Gothic and Baroque is his famous work Vir temporis acti (Ancient Man), the first version of which, dating from 1911, appeared as a large marble torso without arms, with severed legs and a gilded bronze sword stuck on the plinth like a cross; this was sent to the Prussian collector Franz Rose, and upon his death in the following year was donated by his brother Carl to the Königsberg Museum. In addition, Franz Rose owned another specimen, consisting only of the bust, which was donated to the Artistic Association: both have gone missing and we know what they look like thanks to the extraordinary photographs of Emilio Sommariva (Lodi, 1883 - Milan, 1956). From the original version, other specimens were taken by Wildt himself, including the one from 1914, now in the Museo del Novecento in Milan, which, however, presents only the head. However, when the first Vir temporis acti was exhibited at the Milan Triennale, the work drew criticism: it was called immoral because it was too nude, and the poet and critic Nino Salvaneschi (Pavia, 1886 - Turin, 1968) confessed that he could not understand the “morbid deformations of this bizarre artist” who had put “instead of breasts, two sort of buttons for electric light.” And when the marble head was exhibited in Rome at the Society of Amateurs and Culturists in 1915, Wildt was described as “a madman who believed he was astonishing the world with a clumsy and baroque caricature of the truth.”

He experimented by going to the limits of deformation, as can be seen inAncient Man in the Museum of the Twentieth Century: the frowning eyebrows cause the presence of two protuberances on the forehead, the nose is large and misshapen at the tip, the half-open, coarse mouth reveals the lower arch of teeth, and the cheekbones are somewhat pronounced. On the same occasion, however, critics Arturo Lancellotti (Naples, 1877 - Rome, 1968) and Antonio Maraini (Rome, 1886 - Florence, 1963) were astounded by this torment inherent in the Milanese artist’s works: “he seems to revel in astounding the public with the virtuosity of his chisel that sinks into the nostrils, creeps between the teeth and between the hairs of the beard of his virile heads, passes into the pinnae of the ears until the transparency of the cartilage [...] Through Wildt’s stylization, some pieces of sculpture, with their intense, shiny, yellowish patina take on a caricatured character; others have something tormenting in the spasmodic contraction of the muscles of the face, others, finally, in their rigid static offer the sense of a calm and grave solemnity.” And again, “one would almost say that in the face he loves to render especially those parts which from their cartilaginous nature take on a typical appearance. The marble under his hands [...] is transformed almost into a smooth compact matter. One might say that to attain the tactile exquisiteness that art objects sometimes have in these is Wildt’s unconscious tendency.”

His wholly personal style is anchored in the dimension of time that causes a continuous change of form within what German sociologist and philosopher Georg Simmel (Berlin, 1858 - Strasbourg, 1918) calls “cosmic becoming.” Life is a perpetual becoming, a continuous change to which all form is subjected, perceptible by comparison with the past. The latter thus becomes in the artist’s works an element of the passage of time, and it is through a particular expedient that he intends to achieve affirmation over it: the mask. Marco Bazzocchi, in his essay on Wildt’s masks in the exhibition catalog Wildt . The Soul and Forms , which was held in 2012 at the San Domenico Museums in Forli, traces back to Georg Simmel’s thinking the theory that individual facial features are in continuous relationship to each other and create a more concentrated effect than the rest of the body. According to the philosopher, there is a spiritual principle behind the face, which could be called the soul. And it is for this reason that a feeling of spirituality shines through in Wildt’s masks. The effect of drama, concentrated in the faces of his sculptures, is further rendered by the polishing work on the marble.It is from this profound connection between the light reflecting from the marble surface and the dramatic expression of the face that Wildt’s masks evoke a dimension of eternity, transcending the limits of earthly life. For the artist, the cosmic pain that Simmel spoke of is fully concentrated in the individual, especially in the face: to escape from such torment, from the passage of time, Wildt cuts out the forms, empties the eyes, and opens the mouths of the subjects depicted, because it is through these points that pain can escape from man, freeing him from torment. In particular, the artist often creates gaps in the eyes, because through them the passage of an interiority that is released outward takes place.

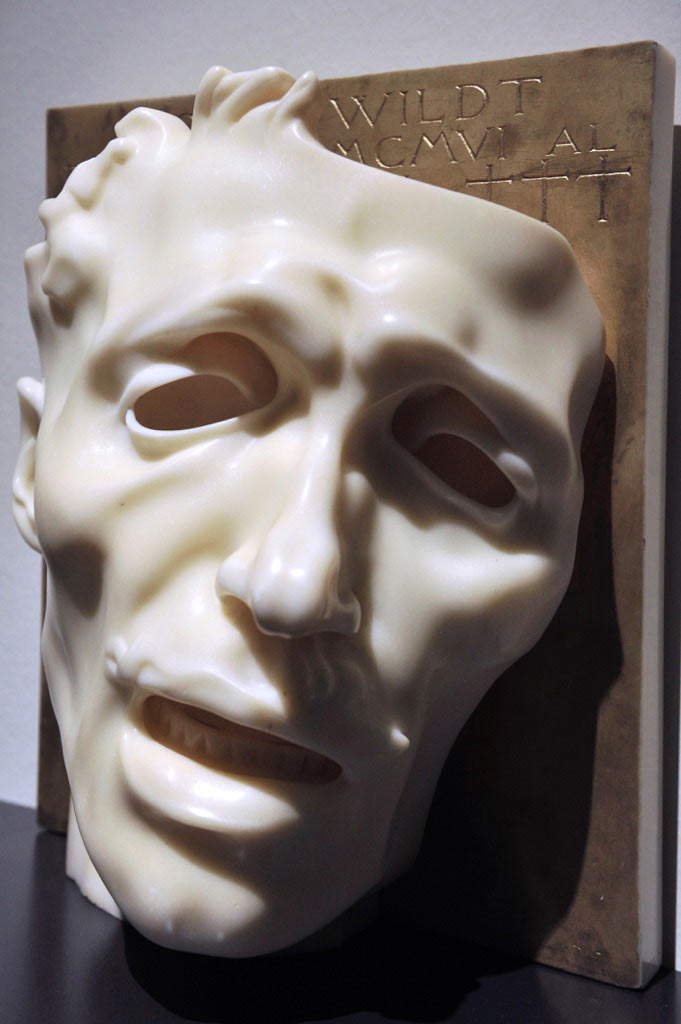

Significant in this sense is his Self-Portrait as a Mask of Pain, a work created in 1909 in marble on a gilded marble ground. This is the physical image of his own torment, following three years of creative impotence. Suffering is tangible in the hollows of the eyes, in the frowning eyebrows, in the mouth half-open in a kind of cry. “In that strange and powerful Mask of Sorrow [...] the long-contained anguish of the impotence to express himself, was converted into a kind of impatient rage of every medium, which drove him to introduce, with direct work, the force refluent to his fingers, in the very hard grain,” said the painter and writer Ugo Bernasconi (Buenos Aires, 1874 - Cantù, 1960). The gold background is not simply a decorative element, but an expression of the singularity of the face-mask: in this case it recalls the backgrounds of sacred depictions, to highlight the cultic value of the work of art, but the gold element can be any detail of a work: a crown, a ribbon, a lock of hair; it will always be representative of a particular value the artist intends to provide to his masterpiece. The original 1909 mask was sent to Döhlau and unfortunately destroyed during World War II bombings; some fragments were found during an excavation campaign carried out in 2002. However, as with the previously mentioned sculpture, the artist made other versions in marble, including the one now housed in the Forlì Civic Museums.

Later, more than a decade after these significant works that had earned him praise and criticism, and following, as stated, his membership in the Novecento Italiano Steering Committee, Wildt decided to participate in 1926 in the I Mostra del Novecento Italiano. An aspect of the artist began to emerge from this occasion, the effects of which can still be felt today: a political aspect, so to speak, which caused him, in addition to numerous criticisms even after his death, a general juxtaposition or identification of his art with the fascist regime. After his death in 1931, there were many critics who denigrated him with the intention of condemning his art to oblivion, and to this day the artist himself is often assumed to be among the exponents of the regime’s art.

It is necessary to keep in mind, however, that his production is strongly linked to the era in which he lived: a time of uncertainties and profound changes to which his art intends to escape through the great mastery and virtuosity with which he manages to master the marble surface. As the critic Ugo Ojetti wrote in Lo scultore Adolfo Wildt: “An artist without peace he is, and without beauty, if by beauty is meant proportion and serenity and, even in pain, the rhythm and cadence that turn cry into song and tumult into harmony. But in this broken torment of his, in this incessant struggle to find, in order to reveal it, an unusual language, in this will to express the invisible and to twist the human body until its soul bursts forth, Wildt is also of a sincerity so frank that perhaps one day he will be regarded as the true exponent of our weary and anxious age, they say, credulous and curious, labored to beat on every stone in the walls of his prison in order to find the way of escape to infinity and hope.”

Returning to the 1926 I Exhibition, the artist decided to exhibit the herma of Nicola Bonservizi, Paris correspondent of the Popolo d’Italia who was killed in 1924 at a young age by the anarchist Ernesto Bonomini. Bonservizi was a friend of Benito Mussolini and founder of the Paris Fascio and the magazine Italie Nouvelle. Wildt created the sculpture, destined for the new Milan headquarters of Popolo d’Italia, in 1925, and it was decided to unveil it on October 28 of that year, on the third anniversary of the March on Rome, in the presence of Mussolini; the latter also composed the epigraph carved on the Siena marble plinth, which reads, “Nicola Bonservizi Fascist journalist fighter sealed with his life the purity of his faith. I die for Italy, he said as he expired. Urbisaglia 2-12-1890 / Paris 26-3-1924.” The marble monument with the bronze portrait of the Fascist martyr, exhibited at the Novecento Italiano Exhibition, was donated to Mussolini for the Galleria d’Arte Moderna in Milan, where it remains today. A work praised during the opening speech of the Exhibition given by Mussolini himself, who proudly emphasized its great return to the Italian tradition, as well as the artistic and symbolic value of the sculpture: “the painting and sculpture represented here are as strong as the Italy of today is strong in spirit and in its will. Indeed, in the works exhibited here we are struck by these characteristic and common elements: the decisiveness and precision of the sign, the sharpness and richness of color, the solid plasticity of things and figures. Look, for example, at the magnificently sculpted head of my poor and faithful friend Bonservizi; does it not appear to you to read in the deep hollow of his dark circles the tragedy of his sudden end?” Ojetti called it “the most admirable [...] of the many masks and busts exhibited by Wildt in these years,” and Sarfatti herself declared: “logical, incisive, clear and without reticence is Adolfo Wildt [...] He is never content with engraving, finishing and polishing [...] All this serves him to despise conquest over matter, and to turn it to other ends; not to please himself. Thus his Bonservizi. The noble head, above the bronze herm, burns, white flame of sacrifice, above an altar.” The color of the Siena marble also recalls that gold background already used in earlier masterpieces to give great value to a particular work.

The artist’s esteem for Margherita Sarfatti is documented in sculpture by a marble work on a bronze base that Wildt created in 1930: the critic and journalist among the most important of the 1920s was portrayed with sweet, delicate and almost noble features, departing in this case from the works mentioned so far, which presented an urgency of liberation through suggestive hollows in the eyes and mouth: here a thoughtful, naturalistic head is depicted, and from the letter she wrote to the artist on August 30, 1930, her appreciation and emotion can be perceived: “I am very moved by your delicate, thoughtful and strong interpretation of me. How well I find myself in it, how well you have understood me, peerless friend and artist! I seem to see in that face a pain, won not tamed, fiercely contained. Is it me like that? I do not know. But she certainly sees, feels, knows! Thank you. Thank you from the bottom of my heart.” Scholar Rachele Ferrario, in her book dedicated to Margherita, wonders if Wildt, in depicting her with a stylized, almost childlike face, with static eyes and a soul already fled away, had not already wished to “freeze her in the motionless time of classicity.” The work is in a private collection, but the plaster cast, donated by Wildt’s heirs, is kept at the International Gallery of Modern Art in Ca’ Pesaro.

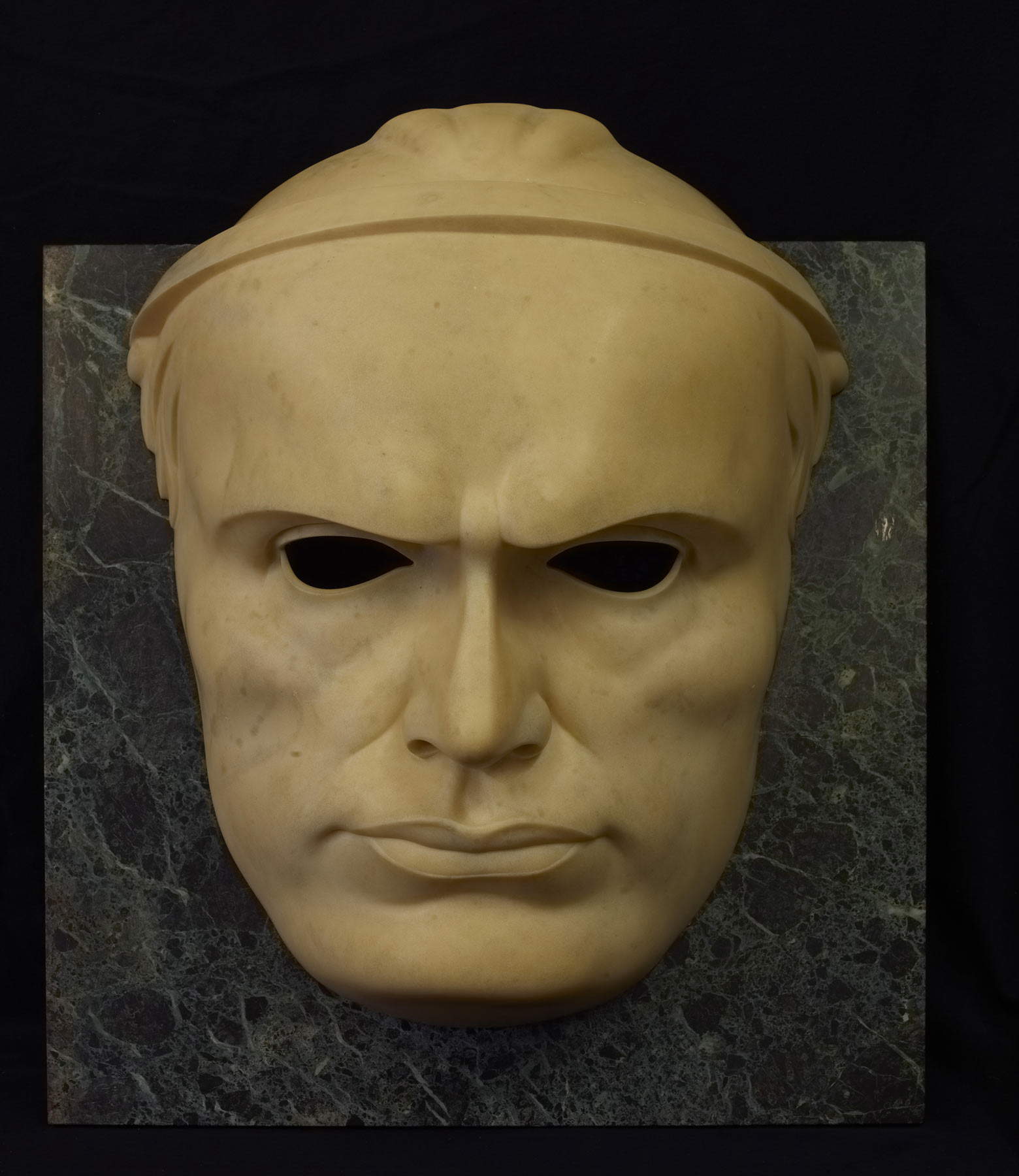

Their friendship was fundamental, as already mentioned, to Wildt’s presence in the artistic and cultural milieu of the time, as she was responsible for joining the Novecento group, for the high regard in which she held his art and personal style, and for the artist’s execution of the portrait of Mussolini, with whom she had a close relationship, since she had written his biography: a work that defined Wildt’s ability to excellently portray figures of power, and that fueled his image as the official artist of the fascist regime. Although he had never seen him, the sculptor completed a bust depicting the Duce using a black-and-white photograph. In the end, it did not result in a bust: it resulted in the mask of a bust. As art historian Elena Pontiggia writes, “Wildt’s Portrait does not express a subject, but an ideal type, captured with visionary sensitivity. What interests the artist is not so much the man Mussolini, with his physical characteristics, but the idea he embodies. It is an idealized expression, emphasized by the frontal pose that accentuates the symmetry and fixity of the face.” Sarfatti herself would recall years later, “the excellent sculptor Wildt did not want to see Mussolini before he molded that bust of him, stamped with such majestic Roman authority, ’I do not want to disturb with the confused testimony of the senses the clear idea I have come to make of him in my head.’” Faced with that square face depicting him, Mussolini fully approved of his portrait and warmly shaking the artist’s hand complimented it by saying that it was truly a work of art. On October 28, 1923, on the occasion of the first anniversary of the March on Rome, the plaster cast of that powerful portrait of Mussolini was exhibited for the first time at the inauguration of the Casa del Fascio in Milan; the following year its bronze casting was present at the Venice Biennale, and in 1925 it was on view at the International Exhibition of Decorative Arts in Paris. Before long, that marble or bronze sculpture of the Duce became an official symbol of the regime, arriving at major Italian and European exhibitions, and was reproduced in numerous printed images in newspapers, postcards, books, and school textbooks. It was a kind of powerful fetish, an image of power that had a wide circulation. The mask that Wildt executed in 1924 on a green marble slab is still on display at the Galleria d’Arte Moderna in Milan. Initially the portrait was the subject of criticism, placed in such an elevated position in a tribune at the 1924 Venice Biennale: “large, stocky to exaggeration the Mussolini is shaped, tanned, shall we say better, Roman style,” wrote La Stampa, and moreover with a forehead too low, but, as Ojetti stated, by then it was an image that lived on its own life so much it became popular, dragging its author with it. In the new headquarters of the University of Milan there was a bronze of it next to the portrait of the king; on the walls of classrooms his image was flanked by the king and the Crucifix, and in 1934 Paoletti’s famous photo of the plaster bust in profile was on the title page of the thirteen volumes published by Hoepli of Benito Mussolini’s Writings and Speeches.

Only three years later than the first exhibition of the Duce portrait, Wildt presented at the Venice Biennale another bust-portrait showing the public yet another power figure, this time, however, from ecclesiastical circles: Pius XI, born Achille Ratti, pontiff from 1922 to 1939, the year of his death. Conceived and begun in 1924, the monumental work was finished two years later and was placed side by side at the 1926 Biennale with St. Francis: at first glance, one notices the opposite character of the two sculptures placed in dialogue in the same edition of the Biennale. That St. Francis with the slender face, in whom the Gothic trait mentioned earlier is found, and whom Ojetti described “with a sheepish blush, with the eyes of a late and stupefied child,” was in sharp contrast to the powerful, solemn and austere Pius XI. And the same power and solemnity is further emphasized by the large golden mitre that the pontiff proudly wears on his head (consider how the use of gold elements harkens back to the importance and uniqueness of the subject portrayed). The marble surface of Pius XI is meticulously finished with goldsmith’s care: for this aspect he was associated with the finery of the Ferrara workshop of Cosmè Tura and Francesco del Cossa or with a Man of Arms by Bramante. Nevertheless, because of its too unreal appearance as it was too shiny, the portrait of the pontiff was described as empty, like a large white and gold porcelain vase, similar to those made by Giò Ponti for Ginori. Indeed, the work elicited a significant amount of criticism: from Margherita Sarfatti who, after noting the comparison between the Gothic asceticism of St. Francis and the “warlike, militia warlike and triumphant catholicity” of Pius XI, asserted that some details, such as the neck and hands, appeared too minutely and painstakingly realistic compared to theaustere hieraticism of the style, to Lancellotti, according to whom Wildt had failed to render the papal majesty by having made “of this marble a precious thing by polishing it like ivory and attending to every detail.” In addition, art critic Michele Biancale had something to say about the installation choice of the sculpture at the Biennale: the statue had been placed in the center of the rotunda under the direct light of a Venini chandelier: “the sanctity of Pius XI is etherized by the amethyst of Venini’s great Murano chandelier, which fills the accentuated reliefs of the face, which under the very rich triregnum looks like a specimen of pontifical majesty, with mobile gleams.” Today the monumental sculpture is housed in the Vatican Museums.

The expression of power was addressed by the artist through yet another prominent figure who had an influential role in the population: king Victor Emmanuel III. His bronze bust is similar in shape and size to Mussolini’s and symbolizes strength, evoked by the oak vines placed around his head. The bronze portrait, which belongs to the Galleria d’Arte Moderna in Milan, depicts the king as a victorious hero, and again aroused the praise of Sarfatti, who stated that this was a “beautiful example of a heroic portrait, though majestically imposing resembling and faithful to the fine features of the Sovereign. No official portraitist, indeed, ever rendered with such precision the thoughtful gentility of lineage. But this effort is evident there in the torment of the chisel on the marble, carved and stylized in the manner of certain orientalizing masks of the late Roman Empire.” This work in fact appeared more realistic than Pius XI: the facial features were more natural, if also minutely detailed. Created in 1929, the work depicting King Victor Emmanuel III, who ascended the throne in 1900 following the assassination attempt on his father Umberto I, was replicated several times in marble and bronze; the head detail was on public view at the 1930 Milan International Fair, and the following year the marble face was exhibited at the first Quadriennale in Rome. It was no coincidence that Wildt executed portraits of these figures, linked by historical events contemporary with the artist: power figures who at that time held control in all spheres, both governmental and ecclesiastical. In the same year as the March on Rome, 1922, Pius XI in fact became pontiff, and later it was Vittorio Emanuele III who asked the Duce to form a government.

There is no doubt that for many years the association of his art with the Fascist regime weighed on the consideration and judgment regarding Wildt’s work, and the sculptor suffered a damnatio memoriae that for quite some time prevented a serene critical placement of his work (the rediscovery has began in the 1980s with the studies of Paola Mola, and has accelerated in recent years, at least since the beginning of the new century, with a renewed wave of studies dedicated to his production, and significant exhibitions). To reread Wildt’s art today without prejudice means, in the meantime, getting to know one of the greatest artists of the early 20th century, recovering his contribution by restoring it to its rightful place in art history, and stepping into the historical, social and cultural context in which he worked, and secondly it also amounts to advancing, more or less explicitly, a more lucid and thoughtful reflection on the relationship between art and politics, without exaggerating in either direction, firmly reiterating the condemnation for certain choices and without omitting what needs to be recounted and explained, but within the framework of a correct contextualization of his production and recognizing the unquestionable value of his works and the extent of the contribution he made to the history of art

Bibliography

This contribution was originally published in No. 2 of our print magazine Finestre sullArte Magazine. Click here to subscribe.

The author of this article: Ilaria Baratta

Giornalista, è co-fondatrice di Finestre sull'Arte con Federico Giannini. È nata a Carrara nel 1987 e si è laureata a Pisa. È responsabile della redazione di Finestre sull'Arte.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.