The Egyptological Collections of theUniversity of Pisa, part of the Athenaeum Museum System, preserve a most precious treasure for the study of Egyptian society: they are the ostrakas of Ossirinco, which represent an extraordinary body of historical, linguistic and cultural evidence of ancient Egypt.

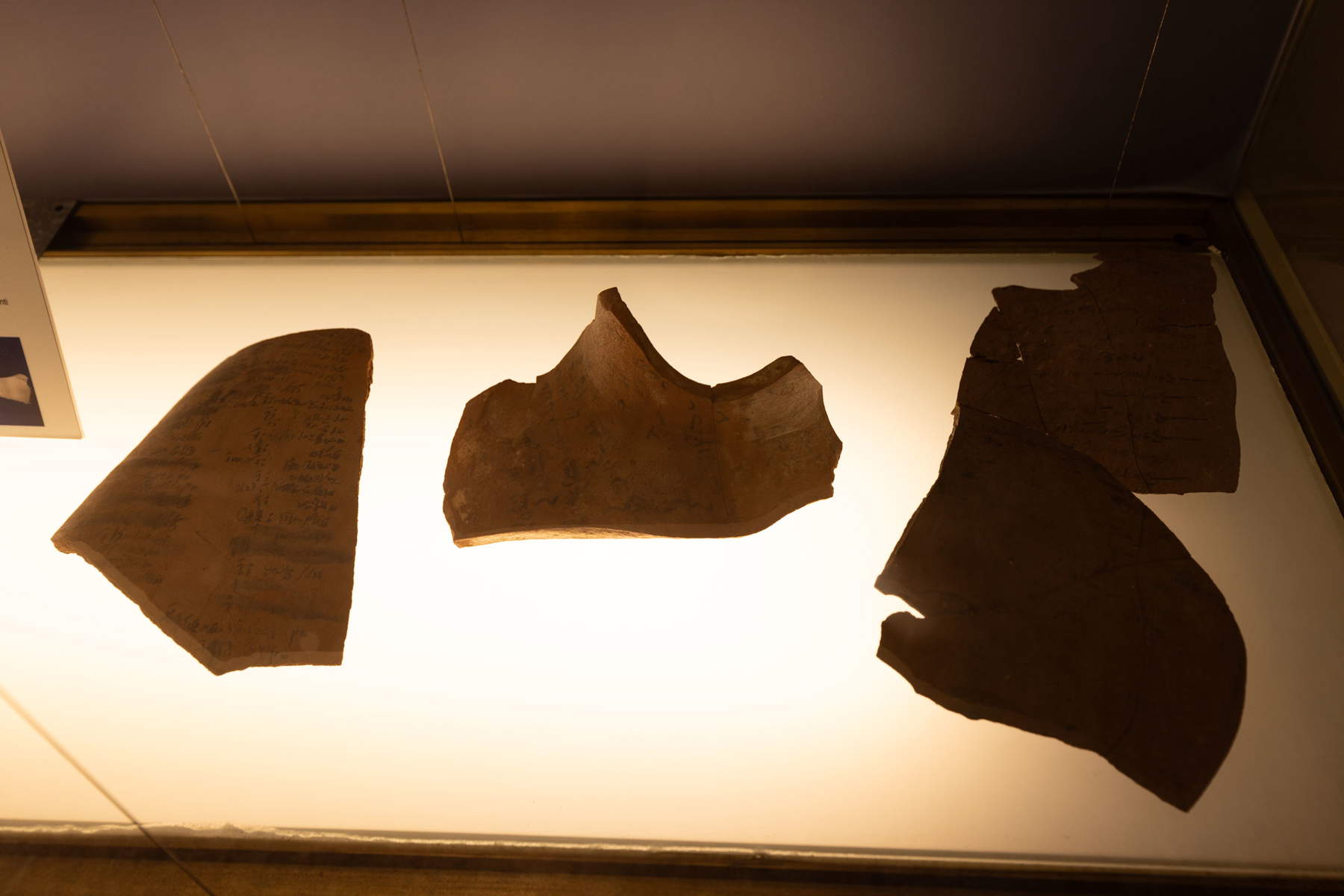

These pottery sherds and other materials were largely discovered during excavation campaigns conducted at the archaeological site of Oxyrhynchus (modern-day El-Bahnasa: the Greek name “Oxyrhynchus” is what the ancient Egyptian city of Per-Medjed took on after Alexander the Great’s conquest of Egypt), located in central Egypt along the west bank of the Nile. The site, famous for the extraordinary amount of papyri found there, was a key source for the study of daily life, bureaucracy and culture in Greco-Roman and Late Antique Egypt. The Pisan collection includes some 1,500 ceramic ostraka, acquired by the University of Pisa in 1968.

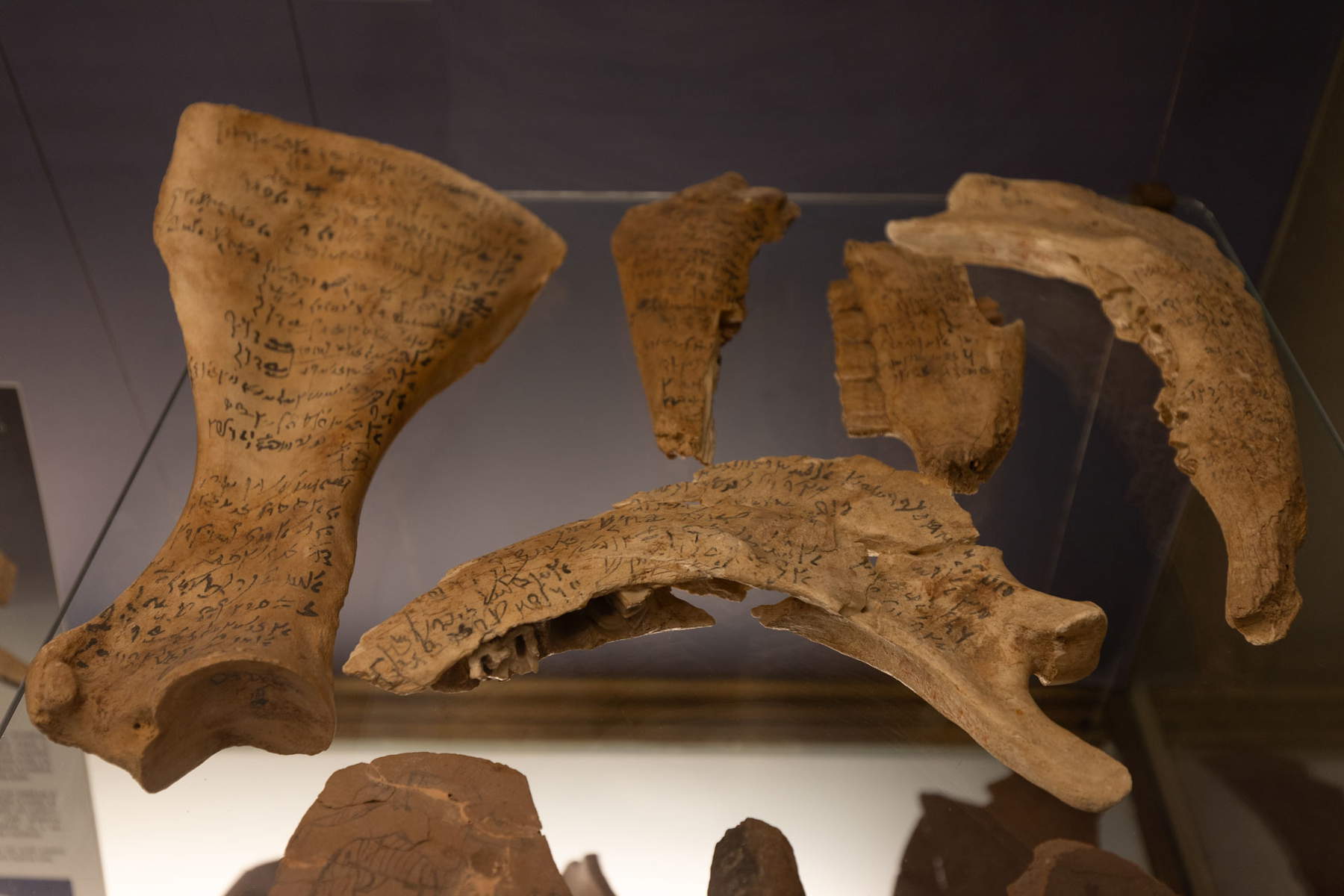

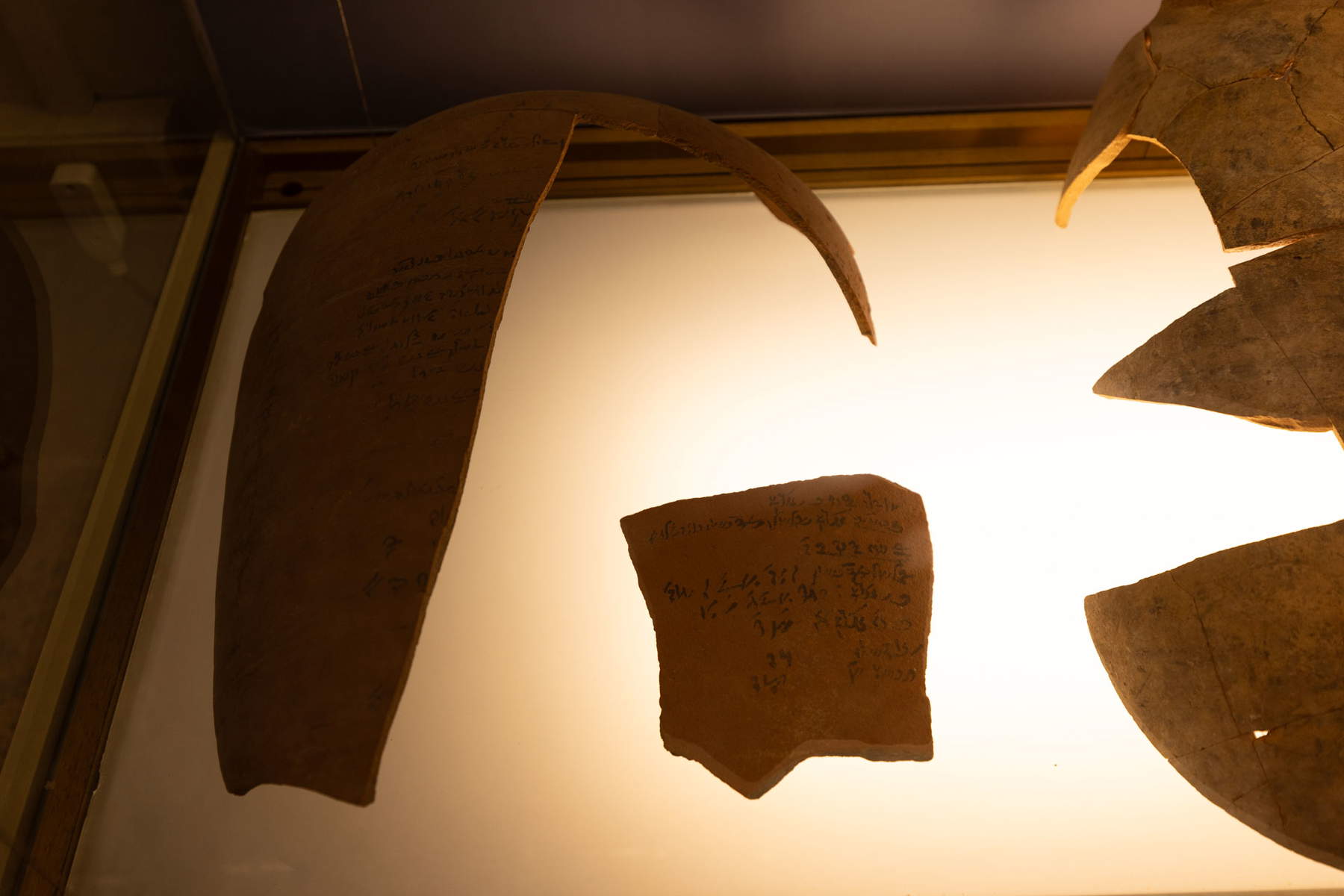

The term ostraka (plural of ostrakon, from Greek ὀστράκον) refers to fragments of pottery used as a writing medium in antiquity. The choice of these materials was related to their wide availability and low cost compared to papyrus, which was more valuable and expensive. However, there was also a material that seems rather bizarre to us today: animal bones. The Egyptological Collections in Pisa, in particular, preserve a dromedary scapula and mandible, the latter particularly recognizable in that it still retains some teeth, where we see signs engraved in demotic. It was not uncommon for animal bones to be used as writing media, precisely because of their easy availability. Ostrakas were used for multiple purposes: administrative documents, memos, accounting lists, receipts.

The ostrakas found at Ossirinco offer a unique insight into Egyptian society in Hellenistic, Roman and Byzantine times, revealing aspects of both daily life and administrative and religious structures. The fragments in the Pisa Egyptological Collections, most of which are written in Demotic (this is the penultimate phase of the Egyptian language, characterized by writing derived from forms of writing in “ieriatic,” a system that developed along with the more famous hieroglyphics), while others are in Greek or Coptic, provide important evidence of the customs and activities of the Egyptian people, since Demotic writing was reserved mainly for common documents. It can be considered a kind of folk writing, in short.

The Ossirinco site is known for having returned one of the largest collections of ancient Egyptian texts, mainly papyri, but also ostraka, all dating from the Roman, Augustan, and post-Augustan periods. The ostrakas from Ossirinco preserved at the University of Pisa come from one of the phases of archaeological exploration conducted at the site between the 19th and 20th centuries. The Pisa collections include materials of great interest to scholars of Egyptology and papyrology.

Among the most common documents are receipts (e.g., relating to supplies of water, grain, oil), records of payments, and lists of goods. Most of the ostrakas concern trade between the city of Oxyrhynchus and the small oasis of Baharia: studying these pottery sherds is therefore crucial to understanding the economic history of Egypt in the Roman period and how trade between Egypt and the oases was organized at the time to which the sherds date (i.e., the time of Roman rule of Egypt).

One of the most fascinating aspects is the linguistic variety. The ostrakas reflect the linguistic and cultural transition that took place in Egypt, highlighting the interaction between indigenous Egyptian culture and Greek and Roman influences. Demotic, a simplified form of hieroglyphic writing used for practical purposes, and Coptic, the last phase of the Egyptian language written with the Greek alphabet, coexist alongside Greek, which dominated in the administrative and literary spheres.

The ostrakas have been studied extensively by Egyptologists and papyrologists, who have analyzed both their textual content and material characteristics. Paleography, that is, the study of writing forms, has made it possible to date the fragments and identify the contexts of production, and material analyses have contributed to a better understanding of the technologies and craft practices of the period.

These are finds of great importance not only to scholars of ancient history and papyrology, but also to the general public. Indeed, they represent a unique window into the daily life of ancient Egypt, revealing concrete details about the administrative practices of this ancient civilization. Their preservation at the University of Pisa’s Egyptological Collections gives scholars access to a valuable resource for better understanding the cultural and social dynamics of ancient Egypt. A fundamental piece of the cultural mosaic of ancient Egypt, in essence: these fragments, although often small in size, contain valuable information that illuminates complex and varied aspects of Egyptian society in Greco-Roman times. Their preservation and study represent a significant contribution to our understanding of the history, language and culture of a civilization that continues to inspire fascination and interest.

The Egyptological Collections of Pisa is a museum regularly open to the public: the website provides practical information on hours and admission fees.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.