Achille Funi. Master of the twentieth century between history and myth

Achille Funi was a pillar of 20th-century Italian artistic expression, and his city is fittingly preparing a solemn exhibition of him at the Palazzo dei Diamanti for October. The painter was born in Ferrara in 1890 and died in Appiano Gentile (Como) in 1972. His creative life thus occupied the whole of the most eventful arc of Italian culture and art of the “short century,” and we must recognize that - within all the adventures, setbacks, ethical, literary and political influences - the intimate vocation to sing the continuity of the figurative outpouring of the Italian soul always guided him. The reference to the pillar is not simply a metaphor of utility but is meant to indicate a structural role, just as it does in architecture, where such a load-bearing member varies in different stylistic contexts but holds firm to the necessary task of the force that enables the regimenting of the building. In this the unceasing source of Funi’s work was energetic, coherent, fluidized by Latin blood and moved by Mediterranean breath.

Before and after the Great War passed him by-beyond the sterile French “avant-gardes”-the restless frenzy of futurism (not without truthful utopian accents), the oscillating pursuit of magic realism, the last pointillism and the new trans-real symbolism: of all these bathing waves he avoided the intrision, receiving rather their secret kernels. The exhibition, curated by Nicoletta Colombo, Serena Redaelli and Chiara Vorrasi, with clarity will make clear the unconditional personality of Achille Funi throughout the decades where Italy would want to endow itself with a distinct character among European peoples, and will testify to the Ferrarese’s central role. Some have said that from his Este youth he always brought with him Schifanoia’s joyful squaderno, the wide and luminous seeing, the inner optimism and the brilliant range of colors; to us it seems that he also brought with him the satisfied calm of that character of the month of April, who stands with folded arms, quiet in his inner thought, contemplating the joy of the ducal land. Certainly Margherita Sarfatti’s prophecy about the extension of the field of Funi’s creative impulse was confirmed by his vocation to fresco painting on large surfaces, and then by his appointment to the professorship for such now rare and difficult application at the Brera Academy: a professorship he retained until after World War II.

The exhibition catalog, which promises to be as important as ever, will illuminate the many contexts that accompanied and gave reflections on Funi’s personality, confirming his strong personality. Funi was surrounded by well-known actors in Italian and international painting with whom he measured himself without submission. He certainly had a distilled attention for Cézanne and Picasso and a rigorous dialogue of firm song with the imaginative mythicism of De Chirico and Savinio (in a certain way also from Ferrara) and with the libellous painting of De Pisis (this one also from Ferrara and a poet), always necessary for those who should then face dreamy chivalrous exploits on Boiardo’s meters.

Behold, the exhibition will bring to the Palazzo dei Diamanti many of his numerous transportable works, but in addition to the masterpieces that have punctuated the artist’s various active decades-collected from European venues-it will invite the observation and enjoyment of the “Myth of Ferrara” that is, to the admirable fresco cycle of the Sala dell’Arengo in Ferrara’s City Hall, included in his astonishing cartoons. In this advance we refrain from a course on the vast critical mirror that the press and publishing industry will perform for their task, but we wish to alert readers to the fulfilling fascination that the personality of Virgil Socrates Achille Funi will offer them, and that the beautiful Ferrara will pose, as always, with its perennial status as a City of Wonders.

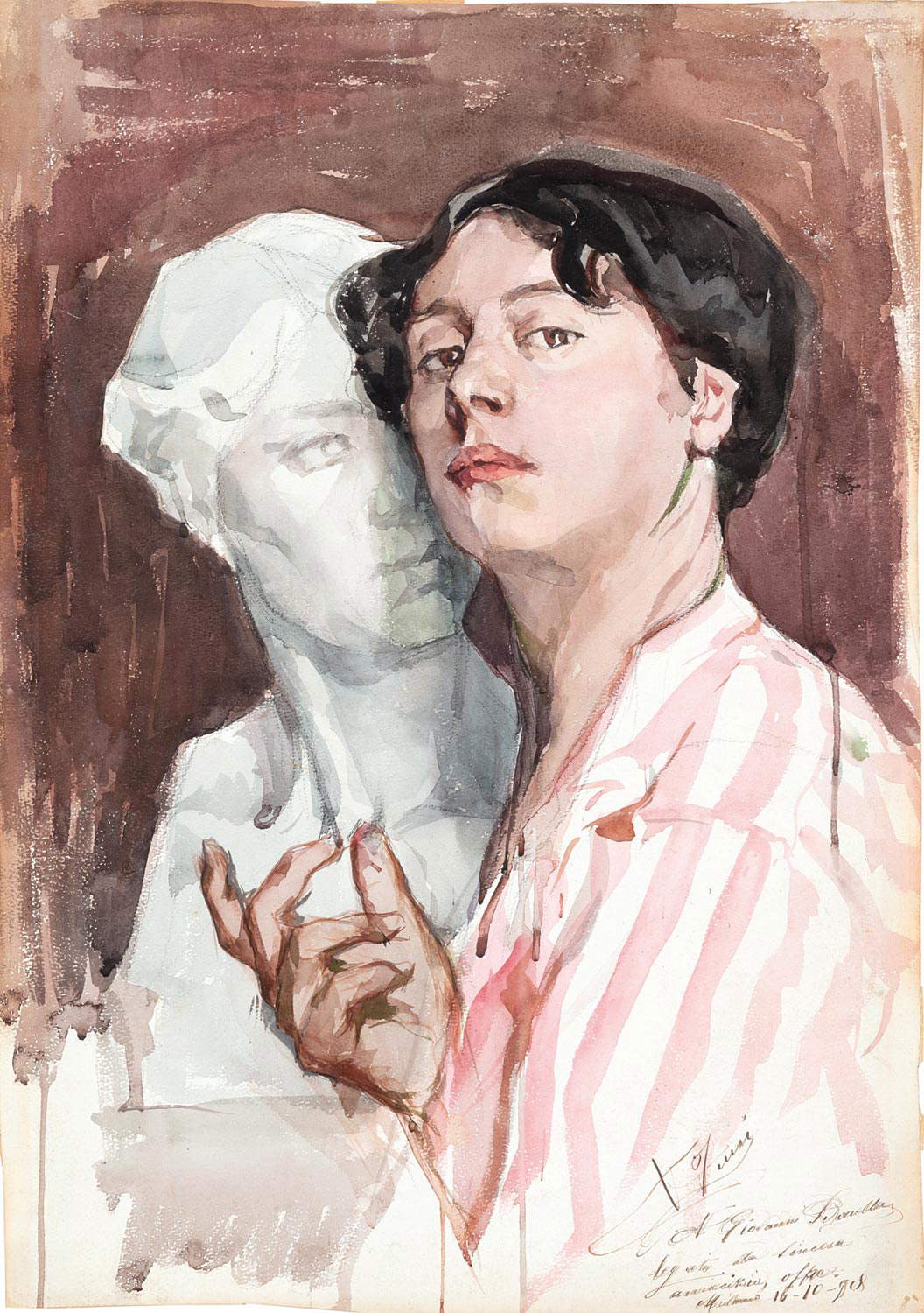

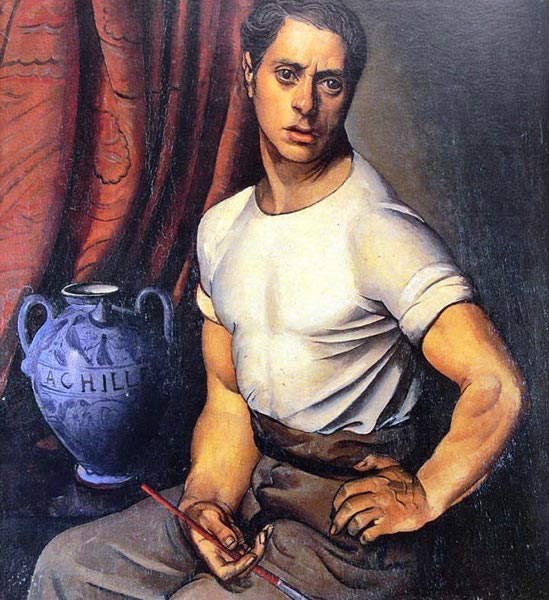

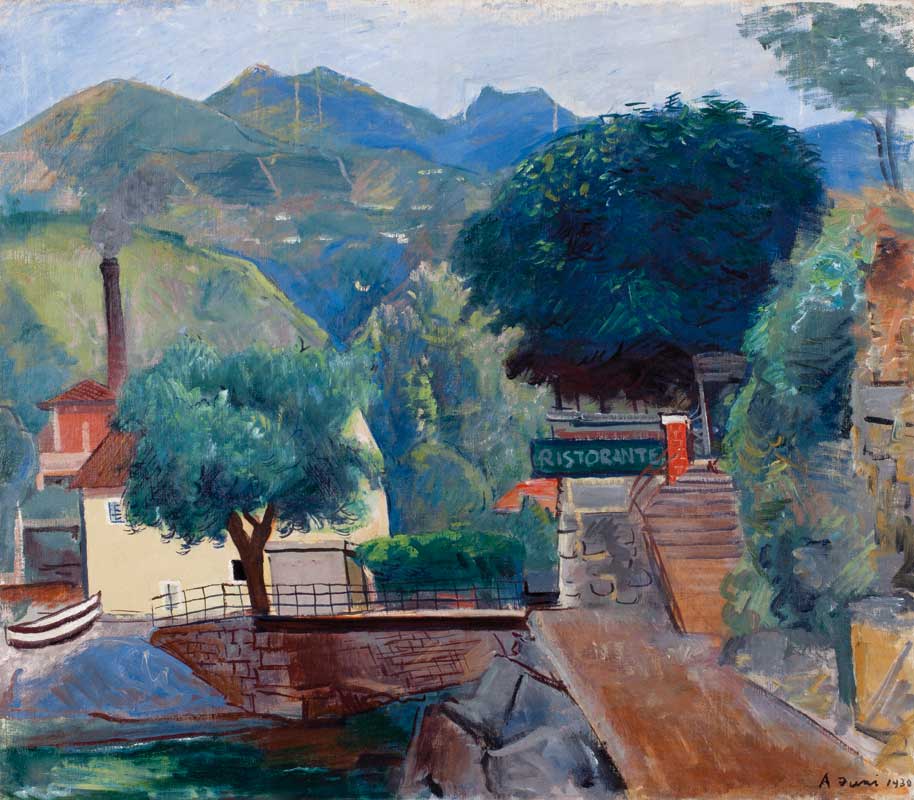

We offer here a brief selection of the painter’s works.

Executed shortly after his arrival in Milan, it virtually stands as a programmatic foundation. The outspoken face of the young 18-year-old artist is juxtaposed with his own semblance replicated in an antique marble. This sort of volitional mirroring marks a vocation that will always be guiding

Of splendid layout this motherhood, which has all the force of the Ferrara tradition, comes after academic studies, after the shocks received from the avant-garde, and after World War I, which forced European art into a constructive “comeback.” Funi, who participated in the creation of the “Novecento” group found himself on congenial and fertile ground. The painting clearly declares the painter’s full possession of the form

Nitid offering, almost an invitation to celebratory participation in the fruits of the fields. The novice Achilles feels within himself the roots of the vast plain on the river and intensely merges visual reality with the whole throb of the spirit that transcends the immediacy of the senses into the mystery of life

Almost a proclamation about himself: having assumed a camp name and a decisive maturity. We are in the year of the “return to order,” and Funi comes peremptorily to the forefront of art

Total painter’s eye the Nostro neglected no receptive emotion. Here with a pure play of colors he creates the landscape depths, the harmonic references and the atmosphere itself

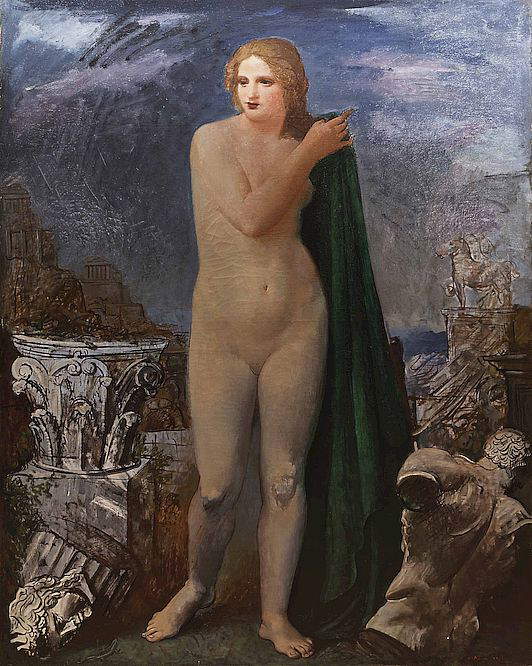

While the two decades between the wars accentuated an empty nationalism, Achille Funi seemed to retreat into silent and evocative archaeological contemplations, barely disturbed by elements of intrusion.

Almost the apex of a historiographical task aimed at the extreme form of Roman pride here the pictorial version stigmatizes the sacrificial act in a few, firm elements. A true contest with sculpture that in evidence is recalled in the figure of supreme Venus at the center of the scene.

Venus, as a goddess of supreme contemplation, will be loved and painted again and again, particularly after trips to Rome and Pompeii

Painting that ranks among the many female nudes whose numbers thicken in the late 1920s but which here, in its mythical evocation, achieves an extraordinary and poetic lightness. One cannot forget a parallel with the levity so close to the paintings of De Pisis, also from Ferrara

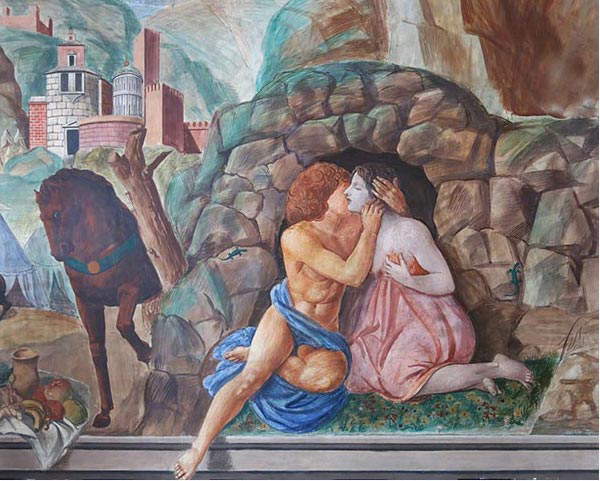

The celebration of the mythical and symbolic events of the City was conducted together with his pupil Felicita Frai, engaging culture, literature and creativity for four years. The cycle fulfilled the artist’s intense protention to fresco on large spaces, as also occurred in several other civil and religious venues

Two parts of great workmanship in the cycle of the Myth of Ferrara, executed in the hall of the Municipal Palace. Here the saint liberator from the mephitic waters, impersonated by the dragon, affirms the citizens’ victory over environmental difficulties and makes him the protector par excellence. The scene of the crusaders at the ransom of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem ties in with the Christian theme of faith and sings the sublime pages of Torquato Tasso’s poem

The detail shows a famous passage from Orlando Furioso, when the Oriental Princess, in love with the handsome Saracen knave “se di disio non vuol morir rompe ogni freno” and the two kiss passionately. Ariosto’s epic is also collected in Achille Funi’s long frescoed plot

And here is the darting hand of the master practicing, pungent and smug, on the figures of the symbolic-astral cycle, as we shall see more fully in the exhibition

Biographical notes

Virgilio Socrates Funi was born in Ferrara in 1890 to a father formerly of Bondeno and a hardworking Mother who together ran a bakery. From age 12 to 15 he attended the “Dosso Dossi” School of Art, then the family moved to Milan. From 1906 to 1910 at the Brera Academy of Fine Arts he took painting classes under the impeccable master Cesare Tallone. He studied anatomy and became interested in ancient sculpture. Between 1914 and 1916 he approached the Futurists and enjoyed the esteem of Boccioni; even after the war, without abandoning the classical vein he measured himself with the times. In this transit he leaves his two first names - Virgil Socrates, or “poetry and wisdom,” a moving àmbit of his father’s orientation - to choose the name “Achilles,” as a sign of strength. (Curiously, we note the period where a certain Giuseppe De Chirico wanted to be called Giorgio, his brother Savinio, and a certain Tibertelli consistently signed himself De Pisis.) The Nostro remained faithful to his vocation ofamor corporis by joining Margherita Sarfatti’s “Novecento” group between 1922 and 1924 and developing a quest for new nobility. Thus he would cover the two decades between the wars, almost with detached aristocracy, not far from Casorati, and facing the occasions of a hidden aspiration, that of the fresco on vast dimensions: from the Church of Christ the King in Rome, to the Municipal Palace in Ferrara, to the Palace of Justice in Milan. He did not even miss a large mosaic in St. Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican. Recognized as a Master from 1939 he taught fresco painting at Brera; from 1945, after the war, he taught and directed the Accademia Carrara in Bergamo, later returning to the chair of ’fresco painting and to the direction of Brera. He led several active years thereafter, called to different cities and honored now by the most attentive critics. He passed away in Appiano Gentile in 1972.

Thanks due to Serenella Redaelli, Anja Rossi, Simone Raddi; the City of Ferrara; and photographer Gianni Porcellini.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.