A very delicate Petrarchan Madonna, that of Zanobi Machiavelli in Fucecchio

On the second floor of the Civic Museum of Fucecchio, in the room dedicated to paintings and minor arts from the 13th to 15th centuries, the visitor’s attention will be captured by a small panel, a delicate Madonna and Child of great elegance and refinement. The author is a 15th-century Florentine artist, painter as well as miniaturist: he is Zanobi Machiavelli (Florence, 1418 - Pisa, 1479). For Vasari he was a pupil of Benozzo Gozzoli: unlikely, given that Benozzo was younger, although in any case Zanobi, especially at a late stage of his career, had shown that he received several suggestions from Benozzo. What is certain is that we can include Zanobi in the group of artists of the so-called “light painting,” a definition widely used since an exhibition held in Florence in 1990 and curated by Luciano Bellosi: an expression by which it is now customary to designate that art which, in mid-15th-century Florence, started from the achievements of Masaccio to rework them according to a renewed interpretation of color, brighter, more luminous, with more defined shadows, with a light that, thanks to skillfully dosed effects, spread through space, making it clearer and even more pleasant. “Painting,” Bellosi wrote in the catalog of that exhibition, “becomes clear, like the sky when it is clear, like the air when it is spring; and even the shadows become sharp and transparent.” Artists such as Beato Angelico, Domenico Veneziano, Alesso Baldovinetti, Giovanni di Francesco, and Benozzo Gozzoli himself were the main architects of this renewal.

|

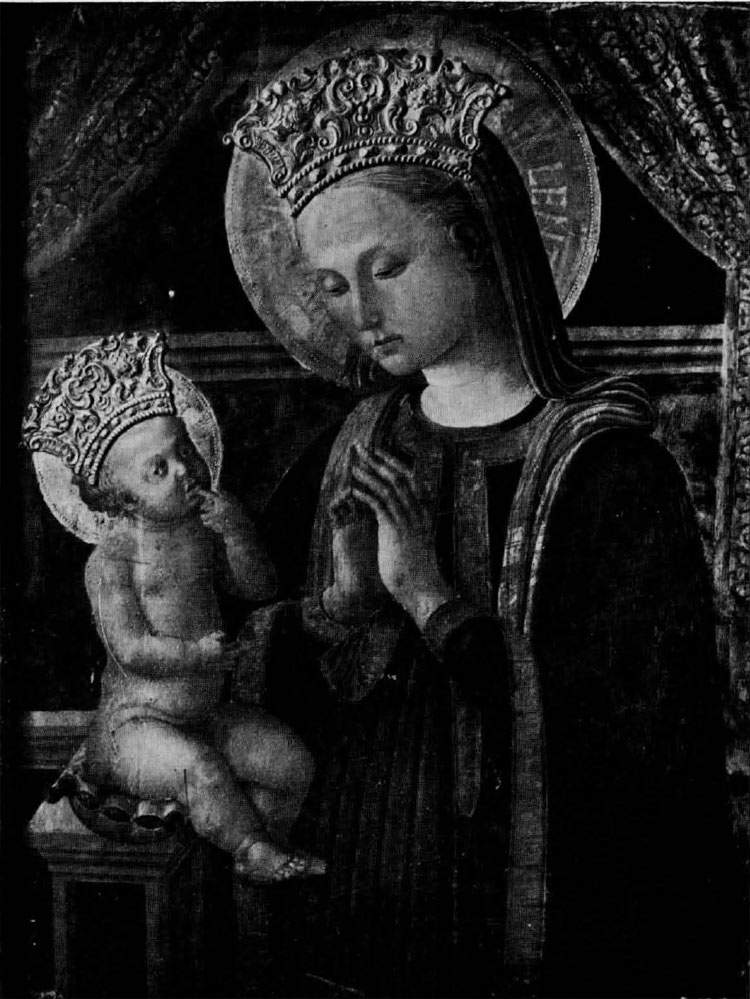

| Zanobi Machiavelli, Madonna in Adoration of the Child (c. 1460-1470; panel, 77.5 x 58 cm; Fucecchio, Museo Civico) |

|

| The room in the Fucecchio Museum that houses Zanobi Machiavelli’s Madonna and Child. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Zanobi Machiavelli, Saint Jacopo (1463; panel, 164.5 x 63 cm; Berlin, Staatliche Museen). Ph. Credit Fototeca Zeri. |

Also participating in this climate is Zanobi Machiavelli’s Madonna and Child, datable to a period between 1460 and 1470 (and for Bellosi himself before 1463), that is, when the light painters ’ research reached its most extreme phase. The work now housed in the Museo Civico di Fucecchio was once in the collegiate church of San Giovanni Battista, the main building of worship in the Tuscan village: it decorated, in particular, the chapel of Santa Lucia. Zanobi’s Virgin has adolescent features, a beautiful rosy face framed by blond hair, uncovered by the veil, parted by a parting and combed back. Surrounding the face is a halo that looks almost like the work of a goldsmith and bears, as iconography dictates, the inscription “Ave Maria gratia plena,” “Hail Mary full of grace.” Our Lady stands in front of her son, her hands clasped in prayer, her gaze absorbed and imperturbable, while he leans out, moves his legs back and forth and, naturally, brings the index finger of his left hand to his mouth, as any child of his age would do (and as Masaccio’s Baby Jesus in the Pisa Polyptych already did: that of Zanobi Machiavelli seems to be a reprise of the Masaccio figure). A curtain, behind the two figures, frames the scene. Behind the protagonists, a wall with a marbled wall, a presence often found in paintings produced in mid-15th-century Florence. Beyond the wall, a garden where pomegranate plants grow: a very peculiar iconographic solution, since the fruit, associated with the Passion of Christ (the red grains allude to the drops of blood poured by Jesus on the cross), is usually held by the Child, or is otherwise in the foreground, in a clearly visible position.

The figures are drawn according to a strict graphic approach: the drawing establishes sharp, precise outlines and gives life to forms that then live in the light, soft colors typical of light painters. It is a particularly dry and sharp sign (see, in particular, the draperies of the Madonna’s red robe, which fall almost perpendicular), to the point of leading a great art historian such as Mario Salmi to attribute the panel precisely to the aforementioned Giovanni di Francesco, since he too demonstrated a similar way of drawing. A manner dependent, moreover, on suggestions provided by the art of Filippo Lippi, another artist to whom the Madonna of Fucecchio is usually tend to be juxtaposed, now assigned without any more doubt to Zanobi Machiavelli (of a work of “Lippesque culture” spoke Marilena Tamassia in her 1993 contribution). And of a “small Lippesque painter close to Zanobi Machiavelli” Carlo Ragghianti also spoke in a 1938 contribution (it is, moreover, no mystery that Zanobi was a painter very close to Filippo Lippi). However, already Bernard Berenson had formulated Zanobi’s name for certain in 1932 in his Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: the evident affinities with an entirely similar Madonna, the one in the Pallavicini collection, and with the San Jacopo conserved in Berlin, a work signed and dated 1463 (a fact that moreover provided a basis for dating the Fucecchio Madonna ), then proved the American scholar right, and today on the name of Zanobi Machiavelli (later confirmed by other art historians, such as Anna Matteoli and Gigetta Dalli Regoli), there is no longer any doubt.

|

| Detail of the Child in Zanobi Machiavelli’s Madonna di Fucecchio |

|

| Detail of the Child in Masaccio’s Polyptych of Pisa |

|

| Zanobi Machiavelli, Madonna and Child with Angels (c. 1460-1470; panel; Rome, Rospigliosi Pallavicini Collection) |

Among the special features for which the painting stands out, an unusual presence should be noted. Observe the edge of Mary’s mantle: one will notice an inscription running along the entire edge. “VIRGIN [...] DI SOL VES[...] CHORON[...] AL SOMO S[...] AMOR MI SPINSE A DIR DI TE PAR[...] CHOMINCI[...] TUA AITA.” The parts of these verses that are missing are hidden from view by the folds of the mantle, but they are sufficient to allow us to recognize some of Francesco Petrarch’s verses in them.In particular, it is theincipit of song 366 (i.e., the concluding one) of the Canzoniere, entirely dedicated to the Madonna: “Virgin fair, who of Sol vestita, / Coronata di stelle, al sommo sole / Piacesti così, che ’n te sua luce ascose; / Amor mi spingse a dir di te parole: / Ma non so ’ncominciar senza tua aita.” We find the same verses on the edge of the mantle with the Madonna from the Pallavicini collection, which, as anticipated, is very close in style to the one preserved in the Fucecchio Museum. In reality, we do not have many elements to understand where the idea of adorning the Virgin with Petrarchan verses originated, and therefore we do not know whether it was the artist who spontaneously inserted the motif because he had a particular fondness for Petrarch’s songs, or whether having successfully experimented with inserting the lyric in one of his panels, he was then asked to replicate it.

|

| Detail of the Virgin’s mantle in Zanobi Machiavelli’s Madonna di Fucecchio |

|

| Zanobi Machiavelli, Madonna and Child with Angels (c. 1460-1470; panel; New Haven, Yale University Art Gallery) |

|

| The Madonna of Fucecchio before restoration |

What is certain is that this is a very fine homage to the Virgin, which we now see mutilated since the work was decurtailed in a past era. And that the work has undergone some retouching, even conspicuous, is shown by the photos that attest to the state of the work before the restorations (it underwent two: one between 1958 and 1967, and one between 1999 and 2001): two crowns had in fact been added to the head of the Madonna and Child, which were then fortunately removed. A Madonna that, with its Petrarchan reference, is very significant because it speaks to us not only of a cultured artist, who knew literature, but also of a somewhat secular cultural milieu, characterized by a humanistic culture that allowed a painter to include, in such a painting, not a religious hymn, but the verses of a poet who had sung love. It must be said that similar quotations were not very frequent, although Zanobi Machiavelli made use of them on other occasions: there is another Madonna, preserved at the Yale University Art Gallery, in which a quotation from Canto XXXIII of Dante Alighieri’s Paradiso appears. Further indication that Zanobi Machiavelli was an artist very familiar with literature.

With the Fucecchio work, Zanobi Machiavelli thus proves himself to be an artist capable of demonstrating good culture and attentive to the stimuli he could find around him, capable of producing a work of great delicacy and elegance, endowed with a decidedly intimate and domestic sentiment but not without preciousness, versatile in its insertion within the framework of a tradition and at the same time introducing original and unusual elements. And his Madonna is important, splendid and remarkable witness to a figurative culture that knew how to go beyond the confines of the city of Florence and radiate much of Tuscany.

Reference bibliography

- Rosanna Caterina Proto Pisani, Museo di Fucecchio. A guide to visiting the museum and discovering its territory, Edizioni Polistampa, 2006

- Rosanna Caterina Proto Pisani, The Museum of Fucecchio’s Collection of Sacred Art, Lo Studiolo, 2004

- Paolo Dal Poggetto, Museum of Fucecchio, STIAV Typography, 1969

- Mario Salmi, Paolo Uccello, Domenico Veneziano, Piero della Francesca and the frescoes of Prato Cathedral in Bollettino d’arte, 3, 28 (1934), pp. 1-27

- Bernard Berenson, Italian Pictures of the Renaissance, Oxford University Press, 1932

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.