"A Touch of Magic. The "sorcerous" Dosso Dossi in his youthful masterpieces between Ariosto and mythology

Few artists can boast of calling themselves truly magical, and Dosso Dossi is among those who belong to this rare genius. Perhaps it is because Dosso is in danger of entrancing us that Berenson suggested, in his seminal North Italian Painters of the Renaissance, that “we should not look too long or too often at his works.” His landscapes, the great American art historian anticipated, evoke the morning of youth, his atmospheres capture us in mystical rapture, his figures convey “passion and mystery.” And to sum up the sensations one experiences when standing in the presence of a Dosso painting, Berenson used a splendid image: “one breathes the air of fairy land.” His very birth remains obscure to this day: we know that his family was of Trentino origin, and that his father Niccolò held a position at the Este court, but we do not know the place where Dosso was born. Perhaps he was a Mantuan from San Giovanni del Dosso, a village of a few souls called Dosso Scaffa at the time and which was under the jurisdiction of the Gonzaga, or perhaps an Emilian from Tramuschio, in the territories of the small marquisate of Mirandola, on the border between Mantua and Ferrara. And between the two cities, between one bank of the Po and the other, between the Gonzagas and the Este, unraveled his existence and formed his culture (although Ferrara was due the clear prevalence): of the young Dosso we know nothing, since the first document that mentions him is from 1512 and presents him to us, evidently, as an already established artist, if he had gone so far as to be commissioned “a large painting with eleven figures” by Marquis Francesco II Gonzaga, who had hired the artist, then 25 or so years old, for the palace of San Sebastiano, then a Gonzaga residence. But we must perhaps imagine him himself enraptured by the ancient epic of a Mantegna, the graceful sentiments of a Correggio, the country allegories of a Lorenzo Costa. And, above all, we must see him subjugated by Giorgionesque lyricism, probably learned in Venice, if we take for granted the hypothesis that there, on the shores of the lagoon, Dosso had to complete his apprenticeship.

However, we find him in Ferrara early, as early as 1513, and, as of this year, he would rarely leave the city to which he became most attached. And we find him well inserted in the worldly climate of the Este court, as well as perfectly at ease in the Ferrara value system: a secular and hedonistic culture, based on good living, on literature aimed at arousing pleasure, on the parties that were regularly given in the “delights” of the lords of Ferrara, on the prolific musical activity that attracted to the city, from all over Europe, the most talented musicians of the time. It was the Ferrara of women, knights, arms and loves that the ill-tolerant Ludovico Ariosto sang about in his Orlando Furioso; it was the Ferrara that, as early as Boiardo, had begun to reread the classics of antiquity not for critical or pedagogical needs but, more simply, to satisfy the curiosities of a public that, however restricted (since we have to imagine it exclusively limited to the courtly milieu), loved to bask in delightful poems and amusing stories; it was the Ferrara of aristocratic luxury that one sought to maintain and constantly raise the level. It was a Ferrara certainly not devoid of contradictions, since very strong were the imbalances between the wealthy classes and the lower strata of the population, a condition moreover typical of Renaissance courts, so much so that Gramsci rhetorically wondered whether, in the 16th century, the rules of chivalric courtesy were perhaps applied to the women of the people. And it was, of course, a Ferrara where the audience for art was, by composition, not so far removed from the audiences of other Renaissance courts: cultured (or pseudo-cultured), sparse, exclusive.

In the catalog of the major exhibition on Dosso Dossi that was held, in three stages between 1998 and 1999, in Ferrara, New York and Los Angeles, art historian Mauro Lucco, to introduce the imaginative world of Dosso Dossi, recalled a passage from Paolo Pino, who in 1548, in his Dialogo di pittura, stated that "painting is proper poetry, that is, inventione, la qual fa apparere quello che non è: and since the painter is like the poet, it is from the latter that he must take example, noting how “in their comedie et altre compositioni vi introducono la brevity.” And in the same way, the artist should avoid “restrignere all the bills of the world in a painting, nor ancho draw the plates with such istrema diligence.” Paolo Pino was writing a few years after Dosso Dossi’s passing, but his prescriptions were a reflection of courtly culture, and it is also for this reason that Dosso’s paintings often appear to us indecipherable, impenetrable, mysterious: because the search for a plot was completely alien to his feeling. Take what is now recognized as his first work, the Nymph and the Satyr from the Pitti Palace collection in Florence, of which we know nothing: neither when it was executed, nor for whom, nor under what circumstances, nor in what place. We only know that it has been in the Medici collections since 1675, and was variously assigned to painters from the Veneto area until Adolfo Venturi’s intuition recognized Dosso’s hand in it. It is a delicate canvas, reminiscent of the best Giorgione (the most obvious similarity is between Dosso’s nymph and the Laura of the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna), especially in the finesse with which the artist treats the background and flesh tones, in the skilful use of sfumato and a soft impasto. The protagonists are two half-length figures: one young woman with her head girded with laurel, a fur coat on her shoulder, the other uncovered to the point of revealing her breasts, and behind her a simian-looking faun, caught in a grimace that exudes eagerness and violence at the same time, so much so that this painting has been read as the description of a chase, but in vain is any attempt to extract a story, or to identify with certainty the two enigmatic characters.

|

| Dosso Dossi (Giovanni Francesco di Niccolò Luteri; San Giovanni del Dosso, 1486? - Ferrara, 1542), Nymph and Satyr (c. 1508-1510; oil on canvas, 57.8 x 83.2 cm; Florence, Uffizi Galleries, Palatine Gallery, Palazzo Pitti) |

|

| Giorgione (Giorgio Barbarelli?; Castelfranco Veneto, 1478 - Venice, 1510), Laura (1506; oil on canvas pasted on panel, 41 x 33.5 cm; Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum) |

The point is that Dosso is not a painter of narratives. He is not an artist who tells us stories: at most he suggests them to us, evoking an atmosphere more than expounding a fact, omitting details (often even those that would normally be diriment to recognizing a given iconography) and concentrating instead on the seemingly futile, the incidental, the relative. “With a skill that has something of the magical, of the sorcerous,” Lucco wrote. Who then is nothing but that touch of magic that Edmund Garrett Gardner spoke of, more akin to the genius of Elizabethan England than that of Renaissance Italy. A magic that made Dosso Dossi thealter ego of Ariosto in painting. Or vice versa. And the Ariosto reference, after all, is often called upon to explain his paintings: it happened also with the Nymph and the Satyr. Mythological skit or fragment ofOrlando furioso? It will be noted that the satyr does not really look like a satyr: he has, yes, a goat’s stubble, but he lacks horns. And, generally, when at that time a painter wanted to paint a satyr, he would equip him with all the elements to ensure that, at the very least, his nature would be recognizable. Just as many questions are raised by the figure of the nymph, especially if one looks at how she is dressed, or if one notices the unusual jewelry, the equally strange fur and the laurel wreath (all elements that are ill-suited to the depiction of a nymph). Thus, in the 1980s, Maria Matilde Simari, taking up a cue from 1911 by the aforementioned Gardner, who had read the two figures interpreting them as Angelica and Medoro, proposed identifying them rather as Angelica and Orlando: the ring that the young woman wears around her neck could be “the annel that repairs every enchantment,” the one that, in Ariosto’s poem, made the wearer immune from enchantments (and this element could also explain why the woman’s imperturbable expression), while the disfigured face of the male protagonist would be enough to make it possible to glimpse an Orlando brutalized by his madness. A plausible reading, although coldly received by later critics, who preferred to stick to the traditional exegesis of the nymph being pursued by a satyr. And as to why the characters deviate so much from the usual iconographies, it would be quickly said: it is necessary to read the painting not already as something faithful to an ancient text on Dosso’s part, but as a “free interpretation from.”

And this freedom was entirely congenial to the painter, if one thinks of the painting in the National Gallery in Washington, which revisits with new freshness and with Dosso’s typical, magical originality the story of the sorceress Circe, here surrounded by a gaggle of animals (a deer, a fawn, two dogs, a few birds) and immersed in the usual Giorgionesque landscape, an admirable essay in tonal perspective, with the tree in the center acting as a backdrop as in The Three Philosophers, with the forest sloping toward the hills in the background, with the sky darkening and the foliage coming as if moved by a light breeze. The enchantress is in the center, nude, while with her arms, in an attitude similar to that of Leonardo’s Leda (but also to that of the young man who appears in Giorgione’s Sunset, in turn reworked by Giulio Campagnola in his Young Shepherd, who was perhaps Dosso’s most immediate conduit), she embraces a table with some inscriptions (presumably her magic formulas), and with her foot she touches a book on which a pentacle is inscribed, leaving little doubt as to her activities. Yet here, too, Dosso departs from any tradition: the rod that, according to the Homeric poem, Circe used to strike men in order to turn them into animals is missing, as are the pigs into which the sorceress had transformed Ulysses’ companions. Calvesi, already in the 1960s, suggested that the naked young woman was actually the nymph Canente, capable of excelling in singing and of attracting even animals to herself, a sort of female Orpheus, in short, of whom Ovid tells in his Metamorphoses: this would eliminate the moralizing aura that, in the Renaissance, often accompanied the representations of Circe (especially in the Florentine sphere: Pico della Mirandola, for example, in a passage against the practice of meretriciousness in his Comment sopra una canzona de amore, wrote that easy women “not only do not induce man to any degree of spiritual perfection, but, like Circe, at all turn him into a beast”), but which would have been so unsuitable for an environment devoted to hedonism such as the Estense court. Calvesi’s reading, however, would make the book with the pentacle and the table with the formulas superfluous. It is therefore more likely that Dosso Dossi drew from the source of Matteo Boiardo’sOrlando innamorato, where the story of the Homeric sorceress is not given as the tale of a perfidious sorceress who distracts the hero from his goal, but rather takes on the poignant contours of a love story gone wrong (“Era una giovinetta in ripa al mare, / così vivamente in viso colorita, / che, chi la vede, par che oda parlare [....] / Vedevasi arivar quivi una nave, / e un cavalliero uscir di quella fuore / che con bel viso e con parlar suave / quella donzella accende del suo amore. / She seemed to give him the key, / under which one looks at that liquor, / with which more times that haughty lady / so many barons had changed to wax. / Then she was seen to be so blinded / by the great love she bore to the baron, / that by her own aerte she was deceived, / drinking to the napo of the incantasone; / And she was in white doe changed into a doe, / and by then taken in a cacciasione / (Circella was called that lady): / Dolesi quel baron che lei tanto ama”). Other scholars have gone so far as to look again for Ariosto’s elements to change the identity of the sorceress to that of the wicked Alcina ofOrlando furioso, but even in this case we would have a negative character: for Circe, it would seem more credible to think that Dosso wanted to give form (complete with “white hind”) to the damsel with the sad fate sung by Boiardo, and certainly familiar to the curtense environment of Ferrara, as well as more able to meet its expectations. Surely, we can rule out that the sorceress of the Odyssey is the woman who attracts the gazes, attentions and admiration of those who, with wonder, watch her emerge from Dosso’s masterpiece hanging in the Apollo and Daphne Room of the Galleria Borghese, just opposite the Bernini group.

|

| Dosso Dossi (Giovanni Francesco di Niccolò Luteri; San Giovanni del Dosso, 1486? - Ferrara, 1542), Circe (c. 1511-1512; oil on canvas, 100.8 x 136.1 cm; Washington, National Gallery of Art) |

|

| Giorgione (Giorgio Barbarelli?; Castelfranco Veneto, 1478 - Venice, 1510), The Three Philosophers (c. 1506-1508; oil on canvas, 123.5 x 144.5 cm; Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum) |

|

| Leonardo painter, Leda and the Swan (c. 1505-1507; oil on panel, 130 x 77.5 cm; Florence, Uffizi Galleries) |

|

| Giorgione (Giorgio Barbarelli?; Castelfranco Veneto, 1478 - Venice, 1510), The Sunset (c. 1506-1508; oil on canvas, 73.3 x 91.5 cm; London, National Gallery) |

|

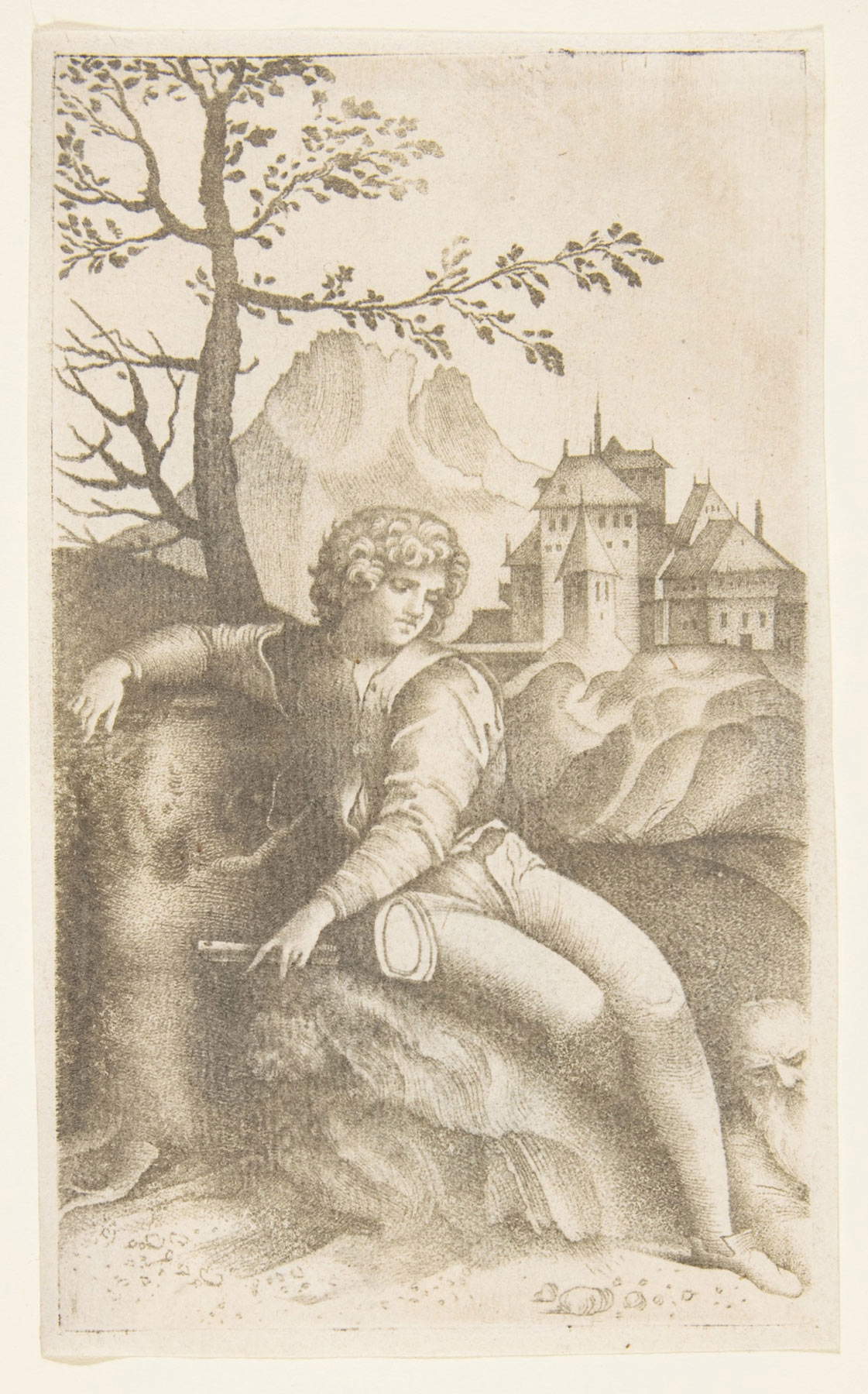

| Giulio Campagnola (Padua, 1482 - after 1515), Young Shepherd (c. 1509-1512; print, 138 x 83 mm; New York, The Metropolitan Museum) |

The woman in the Borghese Gallery, according to Julius von Schlosser’s fitting reading of her as early as 1900, is Melissa, the good sorceress ofOrlando furioso, who with her formulas frees the knights from the spells of Alcina, who used to turn them into plants, into beasts, “into liquid spring,” and according to Dosso perhaps even into baby dolls, if that is how we are to interpret the puppets we glimpse in the upper left corner, hanging from a tree. Imposing like a Michelangelo sibyl, but nobler and more delicate, the fairy Melissa sits in the thicket of a forest, in the center of a magic circle: she is covered in sumptuous robes, with a blue silk robe, dyed with azurite, covered with a scarlet cuirass with golden embroidery and with a golden brocade mantle, and with a precious turban, also golden, on her head. Without crossing the eyes of the relative, she turns her attention to the little puppets, while with one hand she holds a table of formulas, and with the other moves a flashlight with which she lights a brazier. Keeping her company are a molossus looking in our direction, a pigeon perched on armor, another small bird sitting on the ground, and also a rose: there are four of them, corresponding in number to the bamboos on the tree, and in all evidence they are the knights waiting to be freed from the spell of Melissa’s adversary (the breastplate on which the pigeon rests is a rather blatant clue). The landscape behind, inhabited by three presences (three gentlemen conversing among the shrubs, perhaps among those saved from Alcina’s spells), fades into the distance until it meets a turreted fortress that closes it off at the bottom (Alcina’s castle, wanting to continue reading).

The obvious Giorgionesque suggestions (the sky, the landscape, the shape of the trees recall the Tempest, and in the group of seated knights one will be able to discern references to the concerts of the great painter from Castelfranco) are enriched here by the contact with Titian, not only for the warm tones that characterize the painting (and that clash with the cold ones giving rise to surprising contrasts) and for the richness of the clothes, similar to those encountered in the works of the Cadore painter, but also for the female type, which brings to mind theAmor sacro and Amor profano of the Galleria Borghese, an earlier work but painted in the same turn of the years as the Melissa. And then there is, as suggested, the meeting with Michelangelo, which took place on a probable trip to Rome, and the meeting with Raphael (similarities with the Madonna d’Alba will be noted, particularly in the pose, with the leg advancing and one foot sticking out of the robe: even the sandaletto is similar). David Alan Brown also wanted to see in it a quotation from Dürer’s Vision of Saint Eustace (which already may have served as a model for Circe): the dog.

Melissa is a central figure inOrlando furioso especially in relation to her importance to Ferrara: she is the one who saves Ruggiero from Alcina, she is the one who helps the knight and his beloved Bradamante to unite, and she is the one who foresees their future, who lets the two lovers know that the house of Este would be born from their union. The appearance, attire and attitude of Dosso’s fairy would almost seem to give shape to the verses with which Ariosto describes Melissa: “una donzella di viso giocondo, / ch’a’ bei sembianti et alla ricco vesta / esser parea di non ignobil grado; / ma, quanto più potea, turbata e mesta, / mostrava esservi chiusa suo mal grado.” The tools with which the sorceress surrounds herself are those Ariosto gives an account of in Canto III ofOrlando furioso: there is the magic circle, traced on the ground as protection from evil spirits (“poi la donzella a sé richa recall in chiesa, / là dove prima avea tirato un cerchio / che la potea capir tutta distesa, / et avea un palmo ancor di superchio. / And that by the spirits she may not be offended, / he makes her of a great pentacle cover; and tells her to be silent and stand looking at her”), and there are also the flames (“or what nature it is of some marbles / that move the shadows in the guise of facilitles, / or force also of suffumixes and charms / and signs impressed on the observed stars [...]”): the moment narrated in the third canto is one of the fundamental episodes of the poem, for here Melissa predicts to Bradamante, who has arrived to her in male armor, her future and her descendants (“L’antiquo sangue che venne da Troia, / per li duo migliori rivi in te commisto, / will produce the ornament, the flower, the joy / d’ogni lignaggio ch’abbi il sol mai visto / tra l’Indo e ’l Tago e ’l Nilo e la Danoia, / tra quanto è ’n mezzo Antartico e Calisto. / In your progeny with supreme honors marquises, dukes and emperors”). Such an important moment, which for some time Dosso, in all probability, must have decided to depict according to more distinctly narrative intentions than those that were usual for him: in fact, the X-ray taken on the occasion of the 1998 exhibition revealed that, under the painting, the figure of a knight in armor, with an effeminate face, was concealed, accompanying the figure of Melissa, looking at her. It is quite safe to assume that, at first, Dosso wanted to represent a precise juncture, and thus resolved to express in color the encounter between Melissa and Bradamante. An illustration of sorts, in short: not least because the work is contemporary with the publication ofOrlando furioso, given to print in 1516 (Dosso’s Melissa might instead be referred to 1518). But, after reflecting on the result, he must have had second thoughts.

|

| Dosso Dossi (Giovanni Francesco di Niccolò Luteri; San Giovanni del Dosso, 1486? - Ferrara, 1542), Melissa (c. 1518; oil on canvas, 170 x 172 cm; Rome, Galleria Borghese) |

|

| Tiziano Vecellio (Pieve di Cadore, c. 1488 - Venice, 1576), Amor sacro e Amor profano (1515; oil on canvas, 118 x 278 cm; Rome, Galleria Borghese) |

|

| Raphael Sanzio, Madonna of Alba (c. 1511; oil on panel transported on canvas, diameter 98 cm; Washington, National Gallery) |

|

| Albrecht Dürer (Nuremberg, 1471 - 1528), Vision of Saint Eustace (c. 1501; engraving, 350 x 259 mm; New York, Metropolitan Museum) |

Because Dosso had little interest in providing an exact account of Ariosto’s verses. The operation he finally accomplished is therefore of a different kind: he summed up various moments of the story (the description of the sorceress in canto II, the encounter in canto III evoked by the magic circle and the flashlight, the liberation of the knights in canto X) into a single image. A visionary, dreamlike image, at once powerful and refined. For an operation more in keeping with his inspiration, with the environment in which Dosso cultivated his talent, and probably more in accord with the needs of the patron, whoever he was. As it is for the Circe, for the Melissa, in fact, we have no information to help us understand what its initial destination was. But if for the Circe a Mantuan commission has been hypothesized by virtue of later documentary evidence that might support such a thought, for the Melissa the scanty elements in our possession might lead, on the contrary, to Ferrara. We know that it was already at the Villa Borghese in 1650, when it is mentioned in Jacopo Manilli’s guidebook, which speaks of it as a painting “of a sorceress who is casting spells”: later it will be recorded in more detail, in the inventory of 1693, as “a large canvas painting with a Woman representing a Sorceress with a flashlight lighting el foco with a dog and other figures sitting.” And there is nothing to prevent us from thinking that the commissioner of the work may have been Duke Alfonso I d’Este himself, and that the painting met a fate similar to that of several Ferrara works by Dosso that later ended up in Rome because they were given by Alfonso’s descendants to Roman cardinals eager to enrich their collections (Scipione Borghese acquired several paintings from the Este, including the frieze of theAeneid, and theApollo in 1623 is attested in the collection of Cardinal Ludovisi).

The Melissa is the first known Ariosto-themed painting in Italian art, but not only for that reason it represents a watershed in Dosso’s career. It is the pinnacle of his youthful career, together with the Costabili polyptych it is the highest point of his very personal fusion of Giorgione and Titian, it is perhaps also the pinnacle of his magic. From then on, his art would embrace in a more pronounced way that Michelangelism which in the Melissa is barely in nuce, and which would later lead him to a denser impasto, to a more heated vigor, to more heroic, more monumental outcomes, which would then undergo further mutations upon his later contact with the art of Giulio Romano. One element, however, remained unchanged: the extreme freedom of a lyrical, imaginative, often virtuoso artist, always animated by the desire to free himself from sources and to interpret his models through his boundless ingenuity. A freedom that even today allows us to assign to Dosso a role transversal to the canons in which we are used to pigeonhole the artists of his time. And he is, indeed, an artist difficult to summarize. But we need only think that, in canto XXXIII ofOrlando Furioso, he and his brother Battista are mentioned by Ariosto (who probably knew them personally) in the list of the greats: “e quei che furo ai nostri di’, o sono ora / Leonardo, Andrea Mantegna, Gian Bellino, / duo Dossi, e quel che par sculpe e colora / Michel, più che mortale, Angel divino: / Bastiano, Rafael, Tizian, ch’onora / non men Cador che quei Venezia e Urbino.” An artist among the greatest of his time, who with his taste for “transmuting characters, details and symbols,” used “the brush like a magic wand,” according to the effective image of Grazia Agostini. An artist who, in essence, looked more like a poet or a magician than a painter.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.