“The narrative of the Italian Renaissance can no longer be solely or predominantly Tuscan-centric,” explains Francesca Tasso, curator of the Museum of Decorative Arts and the Museum of Musical Instruments at the Castello Sforzesco in Milan, and curator of the exhibition The Body and Soul from Donatello to Michelangelo scheduled precisely at the Castello Sforzesco from July 21 to October 24, 2021. “It would not be correct,” the scholar continues, to continue recounting the Renaissance exclusively from a Tuscan point of view: “in the last thirty years there has been a proliferation of studies on Lombard sculpture, Venetian sculpture, Emilian sculpture, so today we have a much broader vision and picture: Chastel, many years ago, in a very famous book, had spoken of the ’centers of the Renaissance,’ and so it is a must to give the idea of this complexity.” A complexity that germinated in Tuscany and developed in northern Italy through a precise link: the fundamental presence of Donatello ( Donato di Niccolò di Betto Bardi; Florence, 1386 - 1466) in Padua. The great Tuscan artist would return to Florence in 1453 after exactly ten years in the Veneto, which would have a decisive impact on the young Andrea Mantegna (Isola di Carturo, 1431 - Mantua, 1506), and through the figure of the latter the work of the Tuscan sculptor would radiate throughout much of northern Italy, interpreted according to different variables but in any case almost always traceable to the harshness and vigor of the Mantegna sign, which is directly indebted to the more “expressionistic” instances, so to speak, of Donatello’s art. And it was precisely in Lombardy that this component merged with certain “eccentric” elements (as the aforementioned André Chastel had written), probably of Ferrara derivation, to give rise to a terrain on which the powerful Lombard sculpture of the later fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries would germinate.

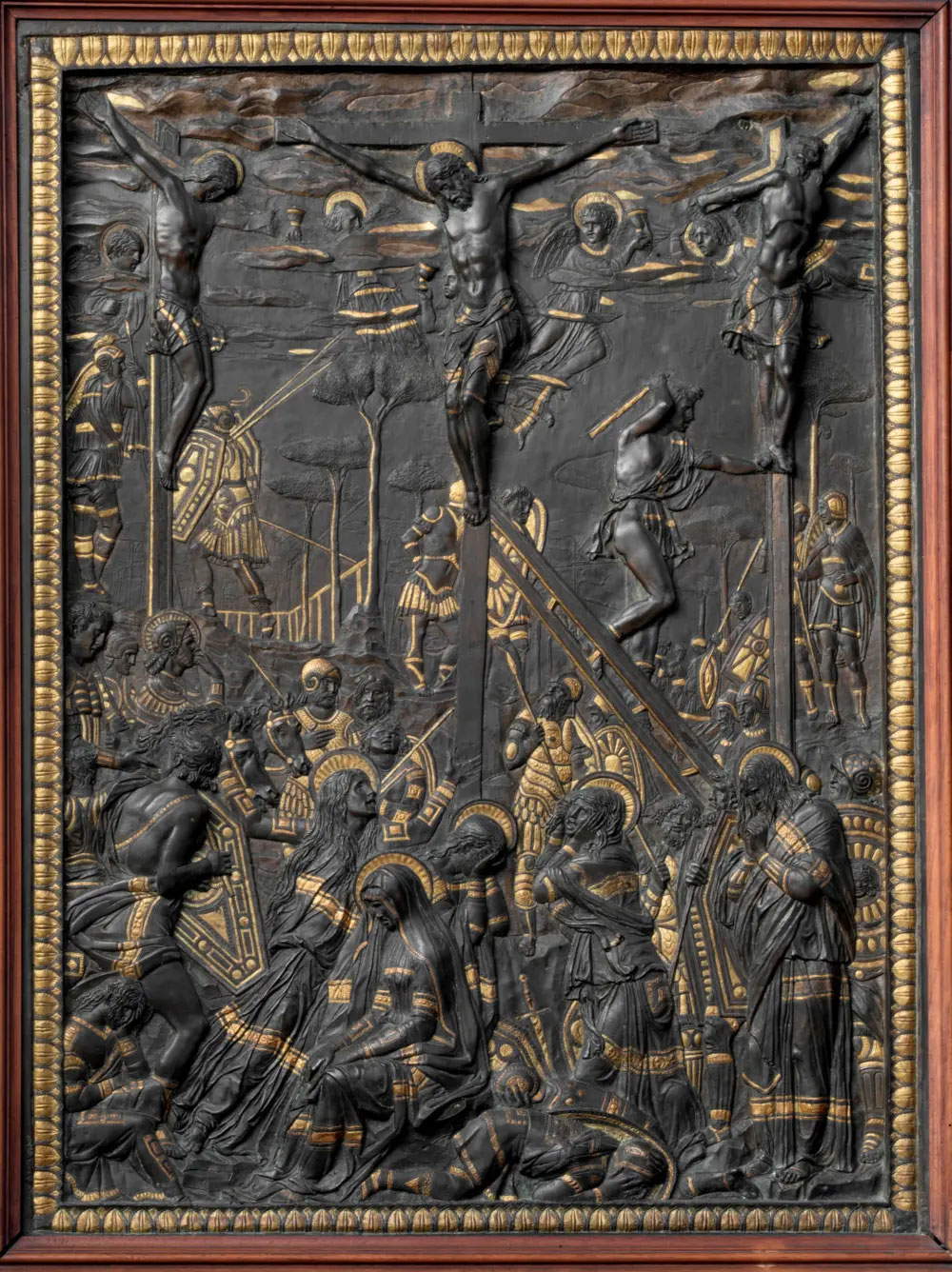

The Milan exhibition at the Castello Sforzesco, summarizing several recent studies (since the early 2000s, northern Renaissance sculpture, especially Lombard sculpture, has become a fervent field of research), highlighted how “certain iconographic themes, because of their particular significance, most directly reflect the innovations brought into play” (so curators Beatrice Paolozzi Strozzi, Marc Bormand and Francesca Tasso): the reference is, above all, to the scenes of the Passion of Christ, which present “the highest rate of compositional novelty and emotional intensity.” A search for pathos that sees precisely in Donatello the first and principal interpreter: one can easily think of the Magdalene of 1453-1455, now preserved in the Museo del Duomo in Florence and originally executed perhaps for the Baptistery, but also of lesser-known but no less innovative achievements: this is the case, for example, of a Crucifixion historically attested (as early as 1553) in the Medici collections but executed perhaps in the latter part of the Paduan sojourn (a work of Donatello invention, with the probable intervention of the workshop in some phases of execution, it is identified by many with the historia domini nostri Jesu Christi de passione in aere commissa cum aura cited in the will of the Florentine nobleman Francesco di Roberto Martelli in 1529), as well as of the more famous Dead Christ that Donatello made between 1446 and 1453 as a decoration for the altar of the Saint in Padua, and of the less famous Lamentation over the Dead Christ now in the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, whose history is unknown before the nineteenth century (there is even speculation that it was made for the Baptistery of Siena), and which has been variously dated by scholars, who have considered it in some cases a youthful work, sometimes a relief made at the time of his stay in Padua, sometimes a sculpture made on his return from the Veneto.

This is a group of sculptures that are quite different from each other, but which have decisive common elements, namely the strong pathetic component and the consequent emotional charge with which these works are imbued (the apex in this sense is probably represented by the London Lamentation: a very strong image, probably also by virtue of its destination, since according to other hypotheses the relief was executed for private devotion), the decisive sign, the tension of the bodies, the suffocating spatiality. Images that Donatello himself had reworked by looking at ancient statuary, and in particular the decorations of sarcophagi: actions, gestures, movements of Roman sculptures are reinterpreted in a Christian key. Donatello’s language will know a considerable diffusion in Lombardy, thanks, as mentioned, to the intermediary of Andrea Mantegna: “Mantegna’s models,” wrote the scholar Marco Albertario, “were already known in the Milanese territory between the end of the eighth decade and the beginning of the next, as confirmed by the reliefs carved by a group of sculptors including Giacomo del Maino and Giovanni Pietro de Donati for the altar of Santa Maria del Monte in Velate.”

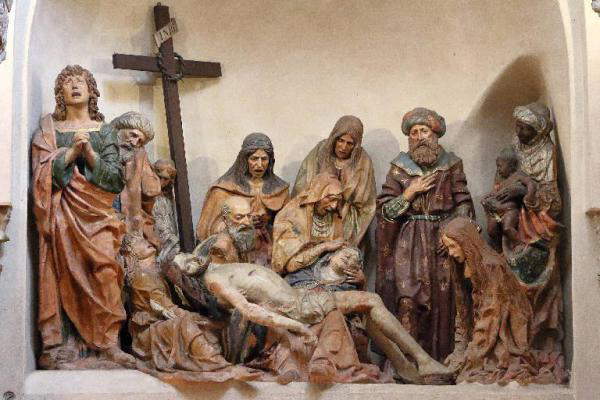

That of the Lamentation over the Dead Christ is indeed one of the subjects from which the penetration of Donatello’s Paduan language into Lombardy is best appreciated. “A true theater of sentiments,” Paolozzi Strozzi, Bormand, and Tasso call it, because although there are variations in the formal scheme, the narrative one always remains similar, with the characters taking almost always the same roles: Jesus’ body conveying all the pathos of the scene, with Our Lady expressing it in an intimate and maternal way and, conversely, St. John and Mary Magdalene indulging instead in gestures of blatant despair; the pious women bringing comfort to Mary; and, usually on either side of the composition, the two material authors of the deposition from the cross, namely Nicodemus and Joseph of Arimathea, who assume more placid attitudes. The aforementioned relief for the altar of Santa Maria del Monte, the work of Giacomo del Maino (Milan, documented from 1459 - Pavia, 1502/1505) and Bernardino Butinone (Treviglio, c. 1450 - post 1510), in its adherence to the originality of Mantegna’s invention of the composition (the scheme almost literally echoes the Deposition that Mantegna engraved in the 1470s: in the composition the Madonna, for example, instead of being close to her son is far away, the last character on the right), follows the typical narrative scheme just described. The strength of the relief by Giacomo del Maino and Butinone, which in its usual location at the Castello Sforzesco is pendant with an Andata al Calvario attributed to the Maestro di Trognano (and in ancient times was part of the decoration, commissioned by the Sforza family as it was ordered by Duke Gian Galeazzo Sforza, of the wooden choir of Santa Maria del Monte in Velate: the other two surviving panels are preserved in situ), is then accentuated not only by the looming landscape of late Gothic derivation, absent in the Mantegna original, but also by the color: it was precisely the chromatic component that made the scene more realistic, and thus was able to bring the faithful closer and make them more involved.

Another key work is the Lamentation over the Dead Christ made before 1485 by the Master of Santa Maria Maggiore, recently identified as the sculptor Domenico Merzagora (active in the late 15th and early 16th centuries), for the church of San Francesco in Locarno, Switzerland, and now instead kept in the Sanctuary of the Madonna del Sasso in Orsellina, also in the Ticino Canton. It is a work where, Albertario wrote, the artist “forces for the first time the limits imposed by the shape of the trunk to impose the figures in space with a freedom experimented until then only by plasticists, while the faces are deformed to express an archaic and essential piety, foreign to the classical model.” The name by which Merzagora has been identified in the past is due to another coeval Compianto, the one in the Museo Civico d’Arte Antica of Palazzo Madama in Turin: it comes from the Church of the Assumption in Santa Maria Maggiore, in the Vigezzo Valley: like the Locarno Compianto, the one in Santa Maria Maggiore expresses a more restrained sentiment and a more compassed gestural expressiveness than would be characteristic of scenes sculpted by artists more receptive to the new language.

This is the case, for example, with the brothers Cristoforo Mantegazza (Pavia, c. 1428 - 1479) and Antonio Mantegazza (Pavia?, c. 1438 - Milan, 1495): to one of them, perhaps to Antonio, is owed one of the most iconic images of Lombard Renaissance sculpture, the Lamentation over the Dead Christ in the Victoria and Albert Museum, a marble relief that constitutes perhaps the lower part of a larger sculpture executed in two portions, and where the expressiveness of Lombard sculpture of the time touches one of its peaks. The disturbing body of Christ, unnaturally elongated with legs and arms extending almost to touch all ends of the relief, is the centerpiece of the scene: Arranged around him are his distraught mother, who tries to embrace him (she is one of the most despairing Madonnas of the period), Magdalene who weeps holding his legs, St. John who, with his face streaked with tears, holds his left arm, and to close the composition on the right Nicodemus or Joseph of Arimathea who pops up behind St. John (note also the beard on Jesus’ left shoulder: it is what is left of the other figure representing Nicodemus or Joseph of Arimathea) and on the left the pious women expressing their affliction, with one of them holding Jesus’ right arm. In this relief everything is designed to engage the relative: the details carved in the round, the angular folds of the robes that seem almost like paper and accentuate the tension of the unfolding drama, the iconography that recalls Nordic models and channels attention to the encounter between Christ and his mother, the expressiveness that still refers to the Paduan Donatello filtered, in this case, by the lesson of Cosmè Tura and the Ferrara artists, precisely because of the elongation of the figures and the angularities. A language, this one that runs through Padua and Ferrara, that was also proper to two other relevant artists of the time, namely Giovanni Antonio Piatti (Milan, 1447/1448 - 1480), whose most significant results can be grasped in some sculptures such as theAnnunciation in the Louvre or the Saint in the Castello Sforzesco, and Giovanni Antonio Amadeo (Pavia, 1447 - Milan, 1522), author of the reliefs of the Colleoni Chapel in Bergamo and, together with Piatti himself, of those of the pulpit of the Cremona Cathedral.

Further testifying to the ramification of cross-references between sculpture and painting is, for example, an exceptional piece preserved in the Museo Diocesano in Mantua, a “pace,” or liturgical object that was offered for kissing by the faithful during celebrations, depicting a Christ in Pieta, the work of Moderno, a pseudonym whose identification has not yet been clarified, although critics are leaning toward narrowing it down to the names of the Venetian Galeazzo Mondella (Verona, 1467 - Rome, before 1528) and the Lombard Caradosso (Cristoforo Foppa; Mondonico, 1452 - Rome, 1526/1527). The scene, in cast silver, chiseled and gilded for some details (the hair, for example), is enclosed within an elaborate architectural frame: the athletic body of Christ is here supported by the Virgin, St. John the Evangelist, and a weeping angel under his right arm. Here, Francesca Tasso has written, “Christ is at the center of an intense emotional relationship with the Mother and with John, in an interweaving of arms, hands, and gazes, according to a search for new forms and new relationships between the figures that certainly developed from the second half of the 15th century in Venetian painting and sculpture, through a reflection on the compositions of Donatello and his Paduan collaborators, transposed by the Bellini workshop and then [...] by the painters of Ferrara and the sculptors of Lombardy.” But not only that: the splendid figure of Christ cannot be explained if not in relation to the research on the body and anatomy conducted in parallel in those years (the work is dated 1513) by artists such as Donato Bramante (Fermignano, 1444 - Rome, 1514) and the Bramantino (Bartolomeo Suardi; documented in Milan between 1480 and 1530). Two masterpieces come to mind, for example, such as the former’s Christ at the Column in the Pinacoteca di Brera, one of the manifestos of Renaissance art, and the latter’s Christ Resurrected, housed instead in the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum in Madrid.

Instead, going back about thirty years to look again at the evolution of polychrome Mourners (wood and terracotta, by virtue of their greater pliability and the fact that they could be easily colored, were the materials that could best and most immediately communicate with the faithful), another fundamental work is the fictile group by Agostino Fonduli (or de’ Fondulis; documented between 1483 and 1522), executed between 1483 and 1491 for the sacellum of San Satiro in Milan, where it still stands today (a rare circumstance for similar groups). It is also an unusual group because it is decidedly abundant: there are not only the eight figures of tradition, but six others appear who are difficult if not impossible to identify, and who were included to accentuate the dramatic character of the scene. Fonduli, a Cremasque artist of Venetian training (he had studied in Padua), engages here in an early essay in Donatello expressionism (as evidenced by the roughness of the forms and the vividness of the sentiment) mediated through the Mantegna lesson as evidenced by the resumption of precise images, but also by some Bramante-esque cues: Fonduli and Bramante, after all, worked together on the site of Santa Maria presso San Satiro (the Marche-based artist was commissioned to arrange the ancient little temple by redesigning a new, larger house of worship around it), and the Lombard was able to take advantage of the proximity of the great architect and painter for an early, embryonic opening to a classicism that would later become manifest in several of his later works.

The interest in the spread of similar groups in this period is then further exemplified by the fact that the confraternity of the disciplini of Gallarate asked Giacomo del Maino in 1485 for a Compianto with “figuras et imagines bonas, pulcras et naturales,” explicitly indicating as a model precisely the Compianto executed by the Master of Santa Maria Maggiore for the church of the Franciscans in Locarno. It is interesting to note how such requests came with a certain constancy precisely from Franciscan circles: “one owes to Franciscan preaching,” Sandrina Bandera wrote, “the diffusion of iconographies related to the theme of the Passion connected to a didactic need. The deepest origin goes back to the Fastentüchers of the Alpine area [...], but they spread to Lombardy and Piedmont through the sacred representations and iconographies of the partitions of Franciscan churches.” The Lamentation of Gallarate is now lost: however, we preserve, also by Giacomo del Maino, but executed in collaboration with his son Giovanni Angelo del Maino (documented from 1494 to 1536) and with Andrea Clerici (Pavia, documented from 1494 to 1512), the Lamentation over the Dead Christ in the church of Santa Marta in Bellano: is a work that is nourished by comparison with the coeval painting of Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci, 1452 - Amboise, 1519), who had moved to Milan in the early 1580s. Giacomo del Maino, moreover, had collaborated with Leonardo: the sculptor was commissioned to make the wooden altarpiece that was to hold the great Tuscan artist’s Virgin of the Rocks. And here, the Del Maino father and son, “urged to produce works that were more and more emotionally involving,” as Marco Albertario has written, “abandoned classical models to arrive at outcomes of greater expressive naturalness thanks to an initial approach to Leonardo’s reflections.” Reflections on Leonardo’s physiognomy that can be grasped by observing the faces, rendered with a descriptive naturalism and with an attention to the contractions of the facial muscles caused by the grimaces of pain, anguish, astonishment and disorientation that suggest precisely a scrupulous observation of Leonardo’s studies.

Reflection on Leonardo da Vinci would open to a new season: it would be the sculptors of the next generation with respect to Giacomo del Maino, the Mantegazza and in general all the artists mentioned above who would direct their art toward a more studied rendering of expressions, “translated,” write Paolozzi Strozzi, Bormand and Tasso, “in gestures and facial expressions, combined with a great freedom in the modeling of the figures.” An early result of this decisive turning point is precisely the Lamentation of Santa Marta, which inaugurates a path that would later lead to Gaudenzio Ferrari ’s sculptures at Sacro Monte in Varallo, the latter anticipated by an early nucleus of chapels that is contemporary with the first sculpted Lamentations from the Lombard area. To this early nucleus also belonged the chapel that housed the Lamentation known as the Pietra dell’Unzione (by virtue of the fact that, in the original arrangement of chapels desired by the founder of Sacro Monte, the Franciscan friar Bernardino Caimi, the Lamentation chapel occupied the position of the Pietra dell’unzione in the Jerusalem basilica located near Calvary), a work attributed to Giovanni Pietro De Donati (Milan, documented from 1470 to 1529) and Giovanni Ambrogio De Donati (Milan, documented from 1480 to 1515), with the probable collaboration of Francesco Spanzotti (documented from 1483 to 1537), to whom some details may refer. The group, after being removed in 1822 from its chapel in Sacro Monte, is now on display at the Pinacoteca Civica in Varallo, and is characterized by traditional attitudes and poses that would later be updated in the next phase of the Valsesian building site, with the arrival of Gaudenzio Ferrari, who would revolutionize not only the relationship between works and worshippers, but also that between the various art forms employed in the chapels.

But even before the birth of the phenomenon of sacred mounts, between the 1580s and the second decade of the 16th century there was a proliferation of groups depicting the Lamentation over the Dead Christ with the aim of involving the faithful in active participation, often the work of authors to whom we have not yet been able to give a name: from the Mantegna-like Lamentation in the parish church of Medole to the very theatrical one in the church of Saints Peter and Blaise in Melegnano, from the group in the crypt of the Holy Sepulchre in Milan to even the more modern works that start from Fonduli’s Lamentation in San Satiro and try to update on Leonardo’s language, such as the terracotta Lamentation in Palazzo Pignano, by Fonduli himself, which has, however, lost its colors. Finally, the question arises as to the relationship in which the mourners from the Lombard area stand in relation to the Emilian mourners, starting with the very famous one by Niccolò dell’Arca in Santa Maria della Vita in Bologna (which, however, represents a dramatic climax that would not later be replicated even in Emilia), and ending with those by Guido Mazzoni: these are works that, Paolozzi Strozzi, Bormand and Tasso write again, “never reach the expressive intensity that Niccolò dell’Arca had demonstrated in Bologna.” Even without considering the fact that Niccolò dell’Arca’s work sanctioned a radical break with tradition, in the Emilian area the models of reference are mainly from Ferrara, rather than from Padua. However, the necessary comparison with Leonardo da Vinci, starting in the early sixteenth century, will lead Lombard artists to investigate in a more refined way the rendering of feelings.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.