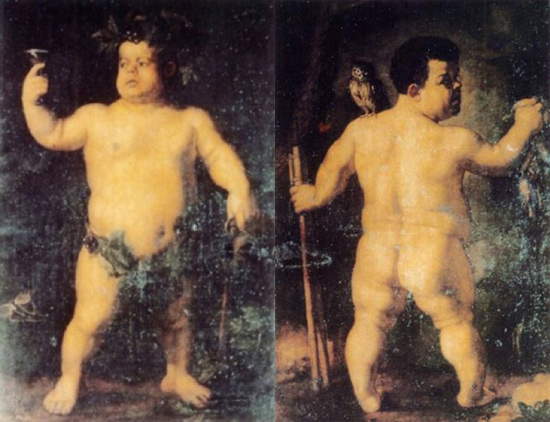

He then portrayed Bronzino to Duke Cosimo Morgante naked dwarf all whole, et in two ways, that is, on one side of the painting the front and on the other the back, with that extravagance of monstrous limbs that dwarf has, which painting in that genre is beautiful and marvelous. This is how Giorgio Vasari described, in the 1568 edition of his Lives, one of the most famous paintings by Bronzino (1503 - 1572), the one depicting Braccio di Bartolo, the dwarf of the court of Duke Cosimo I de’ Medici: originally from Castel del Rio, a village in the Apennines of Bologna, he held the role of jester and jester (a typical role for court dwarfs at the time) and was cynically nicknamed Morgante, like the giant in Luigi Pulci’s well-known poem. This is the same character that Valerio Cioli used as a model for the celebrated Bacchino fountain that adorns the Boboli Gardens in Florence.

|

| Valerio Cioli, Fountain of the Bacchus (1560; white marble, height 116 cm; Florence, Boboli Gardens) |

|

| Bronzino (Angelo Tori), Portrait of the Dwarf Braccio di Bartolo, called Morgante (before 1553; oil on canvas, 149 x 98 cm; Florence, Uffizi), recto and verso |

Such an unusual realization must necessarily have had a purpose: to give a plausible explanation tried, in 1956, the American art historian James Holderbaum, who in an article published that year in Burlington Magazine traced the painting back to the so-called Paragone delle arti, a dispute initiated in 1546 by the man of letters Benedetto Varchi (1503 - 1565), who wanted to involve the major artists of Florence at the time in order to ask them which was the more illustrious art, painting or sculpture. The artists responded by stating their reasons in letters addressed to Benedetto Varchi, and Bronzino argued in favor of painting. Holderbaum believed that Bronzino made the painting within the framework of this dispute, in order to demonstrate the superiority of painting, which, unlike sculpture, would give the artist a way to depict the passage of time: if the front side of the painting depicts the initial moment of the hunt, the back side depicts the end, with the captured prey. This is precisely the meaning that critics today tend to attribute to Bronzino’s work.

The painting then introduces further food for thought. Bronzino’s exceptional descriptive ability, which made him one of the most skilled (but also one of the coldest) portraitists in the entire history of art, and the extraordinary naturalness with which he used to portray his subjects, led many commentators, especially ancient ones, to lavish bizarre celebrations of the work, based on the contrast between the painter’s skill and the feelings of repulsion that the subject aroused in those who observed it. One example is Vasari himself, who appreciates that Bronzino succeeded in a “beautiful and marvelous” painting despite the “extravagance of monstrous limbs” of the dwarf. And again the erudite Domenico Maria Manni, in his Veglie piacevoli (Pleasant Vigils ) of 1759, argued that Cosimo I wanted Braccio di Bartolo to be portrayed “so that the monstrosity all of him might remain visible to the eye of posterity as a marvelous thing.” Today such considerations would be considered ethically unacceptable, but in eras when dwarves fell squarely into the category of “deformed” and “monstrous,” Bronzino’s painting was seen as a demonstration of skill and of painting’s ability to render even subjects capable of provoking revulsion. All this was in line with the artistic trends of the time: artistic debates on the grotesque and the monstrous were spreading (the writings of the Portuguese painter Francisco de Hollanda, in particular, are worth mentioning), and there were not a few artists who had tried their hand at the theme (think of the sculptures in the Monster Park of Bomarzo, or the engravings of Federico Zuccari).

In 2010, on the occasion of the major Bronzino exhibition held at Palazzo Strozzi, the painting of the dwarf Morgante underwent a demanding restoration, one of the most important in recent years: in fact, the work had been heavily altered during the nineteenth century, when it was located at the Medici villa of Poggio Imperiale, because Braccio di Bartolo had been transformed into the god Bacchus. In other words, the owl had been replaced with a goblet of wine, the head of the dwarf had been crowned with a vine leaf, and likewise a sort of loincloth, also made of grapes and vine leaves, was added to the figure of the dwarf.

|

| The painting before restoration, with 19th-century remakes |

The restoration, in addition to integrating the color falls and repairing the cuts and tears that it had suffered over the centuries, totally eliminated the nineteenth-century additions, giving us back the original image as it was intended by Bronzino: after the exhibition, with the opening of the new rooms of the Uffizi, the then director Antonio Natali wanted to place the painting in the center of room 64, one of the two dedicated to Bronzino. So, Braccio di Bartolo now occupies a central role within one of the world’s major museums: with our modern sensibilities, we can think that, despite the mockery the dwarf had to endure during his lifetime, his fame has transcended the centuries and Braccio is now the undisputed protagonist of a painting of immeasurable skill and profound allegorical significance in the context of an illustrious dispute between artists and literati. Qualities that make it one of the most important works of the sixteenth century.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.