Original article: Una novela de André Breton, by Javier Memba (Spanish writer and journalist), published in Descubrir el Arte

Nadja by André Breton is the anti-romance in which the major themes of Surrealism are synthesized. It tells of the platonic love between the father of this avant-garde and his muse. José Ignacio Velázquez’s edition offers a most interesting prologue.

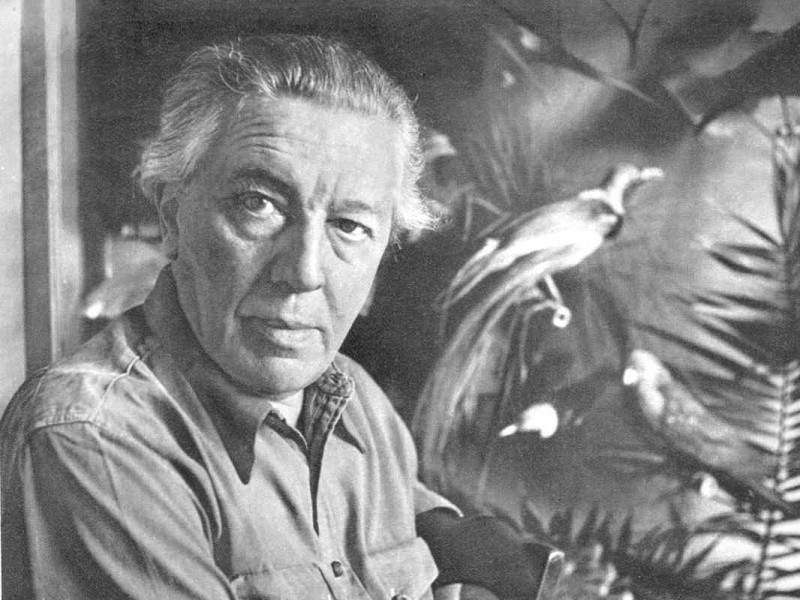

|

| André Breton |

From the first moment I became interested in culture, I was attracted to heterodoxy; needless to say, surrealism (which at first assessment is the greatest subversion of reality) was, from my adolescence, the most fascinating avant-garde for me.

Even before I was acquainted with the artistic and literary avant-gardes of the beloved twentieth century, the eccentricities of Dalí that I saw in my childhood already predisposed me to surrealism. More concretely, it was my friend Gonzalo Rodríguez Cao, who at the school where we both graduated presented an impressive paper on surrealism, who instilled in me a passion for studying what Luis Buñuel called a poetic, revolutionary and moral movement.

In fact, contrary to what is usually thought about its role in art history, surrealism, before being an artistic movement, was a literary movement. The novel par excellence of that glorious age of heterodoxy in the beloved twentieth century was Nadja by André Breton. I read it in a critical edition by José Ignacio Velázquez (with avidity, despite the heaviness due to the profusion of notes in these editions) in November 2002.

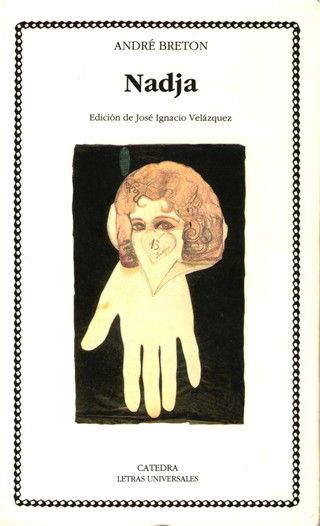

|

| Nadja by André Breton in the Spanish edition edited and translated by José Ignacio Velázquez. |

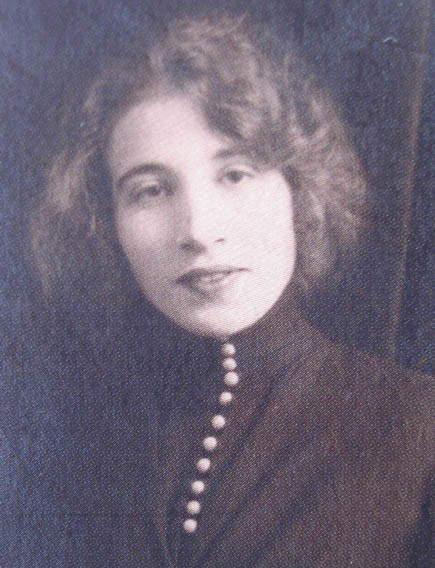

But let us not digress. What matters in the pages of Nadja is the platonic love between André Breton and Léona Camille Ghislaine. Gifted with a particular charm according to men (all black men feel an imperious need to talk to her , Breton confesses), Léona Camille Ghislaine is a clerk, a factory worker, and occasionally even a prostitute and cocaine dealer. Nadja is short for Nadejda. Perhaps the most mythical of Russian women’s names. At least it is for me, who first heard it in a Moustaki song from ’73. In short, Nadja is an anti-romance in which the great themes of surrealism are synthesized. Dream, chance, reality mingle in a relationship between Breton and his muse that lasted from October 4, 1926 to February 1927. On March 21 of that same year, Nadja suffered her first visual and olfactory hallucinations. Being a morose customer, the owner of the hotel where she was staying was not slow to alert the police. After fourteen months interned in the Vaucluse hospital, in 1928 (the year the novel appeared) Nadja was transferred to a psychiatric hospital, where she remained until her death in 1941. The muse of the father of surrealism was only 38 years old, and 14 of them had been spent as a recluse.

|

| Léona Camille Ghislaine |

The very interesting prologue (where, in the second paragraph on page 10, it is erroneously stated that Breton was born in 1996 instead of 1886, but never mind) includes another great annotation on surrealism, as well as an impeccable biographical note on Breton.

Regarding the profusion of notes, which Velázquez himself, if you wish, invites you to ignore, I must point out that I read the ones that really interested me. Undoubtedly, the one I read most is 132 (p. 243) referring to the famous statement beauty will be convulsive or it will not. This is apparently a phrase uttered by Thiers in which he alludes to the republic: it will be conservative or it will not be. Breton concludes that convulsive beauty will be erotic-veiled, explosive-fixed, magical-circumstantial.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.